Spawn This: Minecraft As a Virtual World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master's Thesis: Visualizing Storytelling in Games

Chronicle Developing a visualisation of emergent narratives in grand strategy games EDVARD RUTSTRO¨ M JONAS WICKERSTRO¨ M Master's Thesis in Interaction Design Department of Applied Information Technology Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2013 Master's Thesis 2013:091 The Authors grants to Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothen- burg the non-exclusive right to publish the Work electronically and in a non-commercial purpose make it accessible on the Internet. The Authors warrants that they are the authors to the Work, and warrants that the Work does not contain text, pictures or other material that violates copyright law. The Authors shall, when transferring the rights of the Work to a third party (for example a publisher or a company), acknowledge the third party about this agreement. If the Authors has signed a copyright agreement with a third party regarding the Work, the Authors warrants hereby that they have obtained any necessary permission from this third party to let Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg store the Work electronically and make it accessible on the Internet. Chronicle Developing a Visualisation of Emergent Narratives in Grand Strategy Games c EDVARD RUTSTROM,¨ June 2013. c JONAS WICKERSTROM,¨ June 2013. Examiner: OLOF TORGERSSON Department of Applied Information Technology Chalmers University of Technology, SE-412 96, G¨oteborg, Sweden Telephone +46 (0)31-772 1000 Gothenburg, Sweden June 2013 Abstract Many games of high complexity give rise to emergent narratives, where the events of the game are retold as a story. The goal of this thesis was to investigate ways to support the player in discovering their own emergent stories in grand strategy games. -

How to Use Wurst

How To Use Wurst How To Use Wurst CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MINECRAFT GENERATOR The first site that we are going to talk about today is the website for the popular game Minecraft. This is just another simple mod that you can easily add into your game in order to get the most out of it. The site gives you a lot of the best mods for the game and helps to make it so that everyone will have an easy time finding out what mod they want to use before they install it into their game. The website gives you a description about how the mod works, what kind of features it has, as well as some information about how you should go about installing it into your own version of Minecraft. More Info Download: MINECRAFT", Cook in a skillet over medium heat. Drain any fat and use in recipes or add to pasta sauce. Storage/Leftovers. Raw pork can be kept in the fridge for 2 days or frozen for 2 months (more food safety info here). Keep in freezer bags with the date labeled on the outside. On this page select your currency and confirm your mobile number. The next step is to make sure you're human and not a robot. To do so, just select the box "I'm not a robot. I agree with the Terms and Conditions". After this you will be asked to confirm your email address. Once done, your trial will start.", These are mods that change existing world features, block types, and height levels etc. -

Elytra-Perils-Final.Pdf

Elytra Perils A Gameknight999 Adventure By Mark Cheverton This book is not authorized or sponsored by Microsoft Corp., Mojang AB, Notch Development AB or Scholastic Inc., or any other person or entity owning or controlling rights in the Minecraft name, trademark, or copyrights. Copyright © 2016 by Mark Cheverton Minecraft® is a registered trademark of Notch Development AB The Minecraft game is copyright © Mojang AB This book is not authorized or sponsored by Microsoft Corp., Mojang AB, Notch Development AB or Scholastic Inc., or any other person or entity owning or controlling rights in the Minecraft name, trademark or copyrights. All rights reserved. Books by Mark Cheverton The Gameknight999 Series Invasion of the Overworld Battle for the Nether Confronting the Dragon The Mystery of Herobrine Series: A Gameknight999 Adventure Trouble in Zombie-town The Jungle Temple Oracle Last Stand on the Ocean Shore Herobrine Reborn Series: A Gameknight999 Adventure Saving Crafter The Destruction of the Overworld Gameknight999 vs. Herobrine Herobrine’s Revenge Series: A Gameknight999 Adventure The Phantom Virus Overworld in Flames System Overload The Birth of Herobrine: A Gameknight999 Adventure The Great Zombie Invasion (Coming Soon!) Attack of the Shadow-Crafters (Coming Soon!) Herobrine’s War (Coming Soon!) Box Sets The Gameknight999 Box Set The Gameknight999 vs. Herobrine Box Set (Coming Soon!) Note from the author This is my first short story about Gameknight999. I had intended it to be much shorter, but sometimes, while I’m writing, the story can take control and guide itself to its eventual conclusion regardless of what the author intends; that’s what happened here. -

Minecraft Hacks for 2B2t

Minecraft Hacks For 2b2t Minecraft Hacks For 2b2t CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MINECRAFT GENERATOR taking blocks out cheat in minecraft phone Gravity Gun Mod 1.14.4,1.12.2,1.10.2 and 1.7.10 puts at your disposal two types of weapons, which will allow us to suspend in the air both mobs, animals, or blocks. Once in the air, you can move them, place them where you want or left, and blow them up. Try Minecraft for Free! Download the free trial of Minecraft for devices and consoles like Windows, Mac, Linux, Windows 10, PlayStation, Vita and Android. Minecraft: Java edition for Windows. How to install: * You'll need an Internet connection the first time you launch a game, but after that you can... In addition to our paid generator, we also offer a free service to get a free minecraft download. code Alt Checking Each account is checked before being generated. done_all Alt Information When generating an alt you will be provided with such information as Username, Skin and Capes (if any). Trying a Hacked Client on 2B2T DISCLAIMER: Please do not install hack clients, hacks ruin the fun of Minecraft for other players Today I explored 2b2t, the oldest anarchy server in Minecraft. It was mental. edited by Tommy & @TalentLacking Follow my Twitter ... free schematics for minecraft minecraft mods cheat pour son aim best hack minecraft 1.8 pvp Free Minecraft Servers - minefort.com. How. Details: You have full access to the files of your Minecraft server. You can easily browse your server Details: No server list for Minecraft would be complete without the inclusion of these servers! Upon joining a Skyblock mode server, players get.. -

Navigating the Videogame

From above, from below: navigating the videogame A thesis presented by Daniel Golding 228306 to The School of Culture and Communication in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the field of Cultural Studies in the School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Supervisor: Dr. Fran Martin October 2008 ABSTRACT The study of videogames is still evolving. While many theorists have accurately described aspects of the medium, this thesis seeks to move the study of videogames away from previously formal approaches and towards a holistic method of engagement with the experience of playing videogames. Therefore, I propose that videogames are best conceptualised as navigable, spatial texts. This approach, based on Michel de Certeau’s concept of strategies and tactics, illuminates both the textual structure of videogames and the immediate experience of playing them. I also regard videogame space as paramount. My close analysis of Portal (Valve Corporation, 2007) demonstrates that a designer can choose to communicate rules and fiction, and attempt to influence the behaviour of players through strategies of space. Therefore, I aim to plot the relationship between designer and player through the power structures of the videogame, as conceived through this new lens. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 AN EVOLVING FIELD 2 LUDOLOGY AND NARRATOLOGY 3 DEFINITIONS, AND THE NAVIGABLE TEXT 6 PLAYER EXPERIENCE AND VIDEOGAME SPACE 11 MARGINS OF DISCUSSION 13 CHAPTER TWO: The videogame from above: the designer as strategist 18 PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY 18 PORTAL AND THE STRATEGIES OF DESIGN 20 STRUCTURES OF POWER 27 RAILS 29 CHAPTER THREE: The videogame from below: the player as tactician 34 THE PLAYER AS NAVIGATOR 36 THE PLAYER AS SUBJECT 38 THE PLAYER AS BRICOLEUR 40 THE PLAYER AS GUERRILLA 43 CHAPTER FOUR: Conclusion 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY 50 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. -

Aternos Free Minecraft Server

Aternos Free Minecraft Server Aternos Free Minecraft Server CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MINECRAFT GENERATOR Minecraft Servers are generally run on either a physical server or a virtual private server (VPS). A physical server hosted by the user and rented from third-party companies, ISPs, universities etc. or free services like NFOservers.com, Adverline.pl and VirtualRack.co.uk which are VPS's seems to be the most common way to host your Minecraft Server. A VPS or physical server is better for most, since it is more stable and customizable and can be set up to run on the same machine as the player's computer allowing for an instant jump in to a server when desired.", When you're playing Minecraft and it keeps crashing every time you try to pass level 10/11 or 12, then here's the perfect solution - Minecraft Hack . It's simple, it's easy to use and it doesn't require any other plugins/ add-ons. All you need to know is the level of your character and how much time you're willing to spend on mining resources and building your own world.", Minecraft Servers are great for those who want to play Minecraft with friends, as there is no limit on the number of players allowed and while there are limitations on the maximum number of villagers you can build, you can place practically anything. You will need a high-speed internet connection and a few more dedicated resources than your average computer user may have, so if you are running your server on a VPS or physical machine, it is recommended that you go with an account that offers reliable bandwidth with enough RAM and CPU to keep up with the demands of all players who are online at once.", The great thing about Minecraft is that it gives you unlimited freedom to do whatever you want. -

Embrace the Unexpected: Yet Another Family Conversation

© 2016 TSJLD & Authors ThaiSim Journal: TSJLD Vol. 1, No.1 (Jan-Jun 2016), 38 – 50 Learning Development (TSJLD) ISSN 2158-5539 http://www.thaisim.org/sgld/ Embrace the unexpected: Yet another family conversation Elizabeth Tipton Eastern Washington University, USA James Murff ArenaNet, USA Abstract This paper summarizes a long conversation between an educational game design mother and her entertainment game tester son that began with a discussion about bugs in video games. Along the way, it led to some interesting observations on emergent behavior and metagaming. Finally, this dialog wandered into experiences with emergent gameplay in the design and implementation of pedagogical simulations and games. The importance of good debriefing in the classroom was also underscored. Keywords: bugs; debriefing; designer-player interaction; emergent behavior, intentional emergent gameplay, metagaming, player agency Introduction: Working definitions of Gaming Simulation Four years ago, the authors made public during panel discussions at ABSEL and ISAGA their conversation on improving educational game design through an understanding of the problems commonly seen in during the testing and consumption of entertainment games. Those dialogues have continued to this day. What follows began over dinner one day when the topic was bugs in video games. 38 Embrace the unexpected: Yet another family conversation Tipton & Murff Bugs Bugs, harmless or otherwise, are a common part of software development. You can't predict every single outcome of a particular scenario, especially when the system is extremely complex. While test cases and extensive QA can help, games always ship with glitches ranging from the hilarious-but-harmless to the game- breaking. Some games ship with so many bugs that they are unplayable, but thoroughly entertaining to watch from the perspective of a horrible disaster playing out. -

Free Minecraft Gift Codes

Free Minecraft Gift Codes Free Minecraft Gift Codes CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MINECRAFT GENERATOR RusherHack Player Assistance Utility Mod. RusherHack is a Player Assistance Utility Mod for 1.12.2 designed for 2b2t and other related anarchy servers. RusherHack is not a "cheat client", or a "hacked client", it is a utility/player assistance mod (like OptiFine, Impact, 5zig, Labymod, and countless others). Please note that mods like this are not allowed on some servers and we will not permit ... Minecraft birthday party food labels free printable menu based on dirt coco sc st pinterest also best minecraft images food labels rh pinterest com and fa fff fb fecea birthday party foods cake birthday. The best free hacked Client with awesome fly hack. Enzy. DOWNLOAD. New update, fly bypasses, new gui and theme. Free Minecraft Accounts. DOWNLOAD. DMC is the ultimate free checker . Checks 1000/min unlike Eggcrack that only checks 30/min. You can easily learn DMC in a few minutes and get heaps of accounts. Bloons tower defense 5 hacked Unblocked Games 66 77 76 Unlimited Free Hacked Unblocked Arcade Games. You can play shellshockers.io or krunker.io Online New Unblock Games 2020. Hacked Unblocked Games. Get apps in the App Store on iPad. In the App Store app , you can discover new apps, ... “Search the App Store for cooking apps” or “Get the Minecraft app.” Learn how to ask Siri. You can also tap any of the ... To buy an app, tap the price. If the app is free, tap Get. If you see instead of a price, you already purchased the .. -

Queering Stories and Selves: Gamer Poop and Subversive Narrative Emergence

Issue 9 May 2017 www.intensitiescultmedia.com Queering Stories and Selves: Gamer Poop and Subversive Narrative Emergence Lawrence May and Fraser McKissack University of Auckland Abstract Video games such as Mass Effect 3 (Electronic Arts, 2012), Skyrim (Bethesda Softworks, 2011) and Fallout 3 (Bethesda Softworks, 2008) have been praised for offering highly customisable and personalised ingame avatars, experiences and narrative flexibility. The humour in popular YouTube machinima series Gamer Poop playfully rejects the heteronormative and hypermasculine expectations that still appear inevitable in these seemingly open and inclusive gameworlds. Across Gamer Poop’s 49 videos, stable identifiers of race, gender, and sexuality are radically rewritten using post-production video editing and game modification to allow for intersexual character models, bisexual orgies, and breakdancing heroes—content not programmed into the original games. We discuss the potential for machinima videos to act as tools for negotiating emergent queer narra- tives. These emergent experiences are generated by players and re-inscribed onto the broader video game ‘text’, demonstrating the limitations of video game texts for identity-building activity. Gamer Poop takes advantage of emergence as the ‘primordial structure’ of games (Juul 2005: 73), and presents to the audience moments of emergent, queer narrative—what Henry Jenkins describes as stories that are ‘not pre-structured or pre-programmed, [instead] taking shape through the game play’ (Jenkins 2004: 128). These vulgar and sometimes puerile videos are a critical and playful intervention into the embedded textual meaning of Gam- er Poop’s chosen video games, and demonstrate that a latent representative potential exists in video game systems, rulesets, and game engines for emergent storytelling and identity-building activities. -

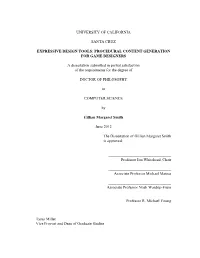

PROCEDURAL CONTENT GENERATION for GAME DESIGNERS a Dissertation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EXPRESSIVE DESIGN TOOLS: PROCEDURAL CONTENT GENERATION FOR GAME DESIGNERS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Gillian Margaret Smith June 2012 The Dissertation of Gillian Margaret Smith is approved: ________________________________ Professor Jim Whitehead, Chair ________________________________ Associate Professor Michael Mateas ________________________________ Associate Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin ________________________________ Professor R. Michael Young ________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Gillian Margaret Smith 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................. ix List of Tables ................................................................................................................ xvii Abstract ...................................................................................................................... xviii Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... xx Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................1 1 Procedural Content Generation ................................................................................. 6 1.1 Game Design................................................................................................... -

The Relationship Between Survival Mechanics and Emergent Narrative

The Relationship Between Survival Mechanics and Emergent Narrative Faculty of Arts Department of Game Design Author(s): Amanda Cohen and Maya Sidén Bachelor Thesis in Game Design, 15 hp Program: Game Design Supervisor(s): Magnus Johansson Examiner: Masaki Hayashi May, 2021 Abstract The Survival games genre is infamous for its lack of narrative. In this paper we look at the possibility of emerging narrative in open world survival sandbox games. The survival aspect of a game is heavily tied to specific survival-centric mechanics that are frequently occurring in the genre. These mechanics and systems can in and of themselves give way to an unwritten narrative for each individual player. By working with the concept of Narrative game mechanics, we interviewed a pool of people about their stories and narrative experiences in survival games. After analysing the results we found recurring patterns to indicate how certain types of survival-mechanics can lead to certain types of narrative situations. Key words: Emergent Narrative, Emergent Gameplay, Narrative Mechanics, Survival Mechanics, Sandbox Sammanfattning Spelgenren 'Survival games' (eller 'Överlevnadsspel') är ökänd för dess minimala fokus på narrativ (berättande). I detta arbete studerar vi de narrativa möjligheterna i 'open-world survival sandbox' spel. Överlevnadsaspekten i ett spel är tätt knutet till specifika spelmekanismer (survival mechanics) som existerar i alla former av Survival-spel. Dessa mekanismer, som delar i ett system, kan av sig själva skapa ett oplanerat narrativ för spelaren. Genom att arbeta med konceptet "Narrative Game Mechanics" intervjuade vi en grupp frivilliga respondenter om deras narrativa upplevelser av survival-spel. Efter att ha analyserat undrsökningsresultatet hittade vi mönster som visade hur vissa typer av "survival mechanics" leder till en viss typ av narrativa situationer. -

Minecraft Thumbnail Maker Free

Minecraft Thumbnail Maker Free Minecraft Thumbnail Maker Free CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MINECRAFT GENERATOR minecraft 1.12 1 cheats christian christmas clip art free downloads santa clipart free download clip art borders free download hd clip art pin Freshmaza New Video Song Download 2014 - WhatsApp Status is minecraft free to download If you are ever unsure how to design a bathroom for your Minecraft home, then this is the video for you! With over 40 unique and creative ideas for a wide ra... can you hack in minecraft on a ps4 download wusrt hack minecraft 1.12.2 This Minecraft tutorial explains how to use cheats and game commands with screenshots and step-by-step instructions. In Minecraft, there are cheats and game commands that you can use to change game modes, time, weather, summon mobs or objects, or find the seed used by the World Generator. In this video, I show you exactly how to make a modded Minecraft server in 1.12.2, so you can start playing modded Minecraft with your friends.Make sure you ... Chisels & Bits превратит «квадратный» дом в живописный особняк с красивой мебелью. ... Chisel — мод на декоративные блоки в Minecraft 1.12.2-1.7.10. Lucky Block Mod для Minecraft 1.12.2. free harry potter minecraft skins minecraft free download apk softonic how to install minecraft all versions for free Play Minecraft Survival game online in your browser free of charge on Arcade Spot. Minecraft Survival is a high quality game that works in all major modern web browsers. This online game is part of the Puzzle, Physics, Mobile, and HTML5 gaming categories.