To Better Understand the Formation of Short-Chain Acids in Combustion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allyson M. Buytendyk

DISCOVERING THE ELECTRONIC PROPERTIES OF METAL HYDRIDES, METAL OXIDES AND ORGANIC MOLECULES USING ANION PHOTOELECTRON SPECTROSCOPY by Allyson M. Buytendyk A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland September, 2015 © 2015 Allyson M. Buytendyk All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Negatively charged molecular ions were studied in the gas phase using anion photoelectron spectroscopy. By coupling theory with the experimentally measured electronic structure, the geometries of the neutral and anion complexes could be predicted. The experiments were conducted using a one-of-a-kind time- of-flight mass spectrometer coupled with a pulsed negative ion photoelectron spectrometer. The molecules studied include metal oxides, metal hydrides, aromatic heterocylic organic compounds, and proton-coupled organic acids. Metal oxides serve as catalysts in reactions from many scientific fields and understanding the catalysis process at the molecular level could help improve reaction efficiencies - - (Chapter 1). The experimental investigation of the super-alkali anions, Li3O and Na3O , revealed both photodetachment and photoionization occur due to the low ionization potential of both neutral molecules. Additionally, HfO- and ZrO- were studied, and although both Hf and Zr have very similar atomic properties, their oxides differ greatly where ZrO- has a much lower electron affinity than HfO-. In the pursuit of using hydrogen as an environmentally friendly fuel alternative, a practical method for storing hydrogen is necessary and metal hydrides are thought to be the answer (Chapter 2). Studies yielding structural and electronic information about the hydrogen - - bonding/interacting in the complex, such as in MgH and AlH4 , are vital to constructing a practical hydrogen storage device. -

EPA Method 8315A (SW-846): Determination of Carbonyl Compounds by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

METHOD 8315A DETERMINATION OF CARBONYL COMPOUNDS BY HIGH PERFORMANCE LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPHY (HPLC) 1.0 SCOPE AND APPLICATION 1.1 This method provides procedures for the determination of free carbonyl compounds in various matrices by derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH). The method utilizes high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet/visible (UV/vis) detection to identify and quantitate the target analytes. This method includes two procedures encompassing all aspects of the analysis (extraction to determination of concentration). Procedure 1 is appropriate for the analysis of aqueous, soil and waste samples and stack samples collected by Method 0011. Procedure 2 is appropriate for the analysis of indoor air samples collected by Method 0100. The list of target analytes differs by procedure. The appropriate procedure for each target analyte is listed in the table below. Compound CAS No. a Proc. 1b Proc. 2 b Acetaldehyde 75-07-0 X X Acetone 67-64-1 X Acrolein 107-02-8 X Benzaldehyde 100-52-7 X Butanal (Butyraldehyde) 123-72-8 X X Crotonaldehyde 123-73-9 X X Cyclohexanone 108-94-1 X Decanal 112-31-2 X 2,5-Dimethylbenzaldehyde 5779-94-2 X Formaldehyde 50-00-0 X X Heptanal 111-71-7 X Hexanal (Hexaldehyde) 66-25-1 X X Isovaleraldehyde 590-86-3 X Nonanal 124-19-6 X Octanal 124-13-0 X Pentanal (Valeraldehyde) 110-62-3 X X Propanal (Propionaldehyde) 123-38-6 X X m-Tolualdehyde 620-23-5 X X o-Tolualdehyde 529-20-4 X p-Tolualdehyde 104-87-0 X a Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number. -

Toxicological Profile for Formaldehyde

TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE FOR FORMALDEHYDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry July 1999 FORMALDEHYDE ii DISCLAIMER The use of company or product name(s) is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. FORMALDEHYDE iii UPDATE STATEMENT Toxicological profiles are revised and republished as necessary, but no less than once every three years. For information regarding the update status of previously released profiles, contact ATSDR at: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Toxicology/Toxicology Information Branch 1600 Clifton Road NE, E-29 Atlanta, Georgia 30333 FORMALDEHYDE vii QUICK REFERENCE FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS Toxicological Profiles are a unique compilation of toxicological information on a given hazardous substance. Each profile reflects a comprehensive and extensive evaluation, summary, and interpretation of available toxicologic and epidemiologic information on a substance. Health care providers treating patients potentially exposed to hazardous substances will find the following information helpful for fast answers to often-asked questions. Primary Chapters/Sections of Interest Chapter 1: Public Health Statement: The Public Health Statement can be a useful tool for educating patients about possible exposure to a hazardous substance. It explains a substance’s relevant toxicologic properties in a nontechnical, question-and-answer format, and it includes a review of the general health effects observed following exposure. Chapter 2: Health Effects: Specific health effects of a given hazardous compound are reported by route of exposure, by type of health effect (death, systemic, immunologic, reproductive), and by length of exposure (acute, intermediate, and chronic). -

Influence of Impurities in a Methanol Solvent on the Epoxidation of Propylene with Hydrogen Peroxide Over Titanium Silicalite‐1

Supplementary Materials Influence of Impurities in a Methanol Solvent on the Epoxidation of Propylene with Hydrogen Peroxide over Titanium Silicalite‐1 Gang Wang, Yue Li, Quanren Zhu, Gang Li, Chao Zhang, and Hongchen Guo* State Key Laboratory of Fine Chemicals and School of Chemical Engineering, Dalian University of Technology, No. 2 Linggong Road, Dalian 116024, PR China; [email protected] (G.W.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (C.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +86‐411‐84986120 Received: 23 November 2019; Accepted: 18 December 2019; Published: date Table S1. Influence of fusel alcohol content on the product distribution and turnover numbers in epoxidation of propylene with H2O2a Conten Selectivity, % Impurity TONb t, wt.% 1M2Pc 2M1Pc PGc DGMEc PGMEc AAc PAc ATc noned 0.00 314.5 0.50 0.52 0.17 0.08 0.00 0.23 0.06 0.00 ethanol 1.00 296.8 0.48 0.46 0.17 0.06 0.01 0.22 0.06 0.00 1.50 286.8 0.45 0.45 0.15 0.05 0.02 0.26 0.06 0.01 2.00 282.9 0.38 0.42 0.14 0.04 0.02 0.28 0.07 0.01 2.50 267.9 0.38 0.41 0.14 0.03 0.03 0.29 0.07 0.01 2‐propanol 0.50 296.8 0.45 0.49 0.17 0.06 0.00 0.21 0.07 0.03 0.75 286.8 0.43 0.47 0.15 0.06 0.00 0.22 0.07 0.05 1.00 282.9 0.41 0.47 0.15 0.04 0.00 0.25 0.08 0.07 1.25 267.9 0.37 0.38 0.14 0.03 0.00 0.26 0.09 0.08 1‐propanol 0.50 297.7 0.51 0.55 0.18 0.06 0.00 0.21 0.11 0.00 0.75 289.0 0.45 0.49 0.18 0.05 0.00 0.22 0.11 0.00 1.00 282.5 0.44 0.49 0.17 0.05 0.00 0.24 0.14 0.01 1.25 266.0 0.43 0.48 0.16 0.05 0.00 0.26 0.14 0.01 Note: a Reaction conditions: pre‐adsorbed TS‐1 powder 0.4 g, fresh methanol or simulated methanol solvents containing ethanol, 2‐propanol and 1‐propanol 35.5 mL, H2O2 (50 wt.%) 4.5 mL, NH3∙H2O (0.32 mol/L) 0.2 mL, propylene pressure 0.6 MPa, 50 ℃, 1 h. -

Propionaldehyde Pad

PROPIONALDEHYDE PAD CAUTIONARY RESPONSE INFORMATION 4. FIRE HAZARDS 7. SHIPPING INFORMATION 4.1 Flash Point: 7.1 Grades of Purity: 97-99+% Common Synonyms Liquid Colorless Suffocating, –22°F O.C. 7.2 Storage Temperature: Ambient Methyl acetaldehyde unpleasant odor 4.2 Flammable Limits in Air: 2.6%-16.1% Propanal 7.3 Inert Atmosphere: No requirement 4.3 Fire Extinguishing Agents: Carbon Propionic aldehyde 7.4 Venting: Open (flame arrester) or pressure- dioxide or dry chemical for small fires, Propyl aldehyde Floats and mixes slowly with water. Flammable, irritating vapor is vacuum Propylic aldehyde produced. alcohol-type foam for large fires. 4.4 Fire Extinguishing Agents Not to Be 7.5 IMO Pollution Category: C Used: Water may be ineffective. 7.6 Ship Type: 3 Keep people away. Avoid contact with liquid and vapor. Wear goggles, self-contained breathing apparatus, and rubber overclothing 4.5 Special Hazards of Combustion 7.7 Barge Hull Type: Currently not available (including gloves). Products: Not pertinent Shut off ignition sources and call fire department. 4.6 Behavior in Fire: Vapor is heavier than 8. HAZARD CLASSIFICATIONS Stay upwind and use water spray to ``knock down'' vapor. air and may travel considerable distance Notify local health and pollution control agencies. to a source of ignition and flash back. 8.1 49 CFR Category: Flammable liquid Protect water intakes. 4.7 Auto Ignition Temperature: 405°F 8.2 49 CFR Class: 3 4.8 Electrical Hazards: Not pertinent 8.3 49 CFR Package Group: II FLAMMABLE. Fire Flashback along vapor trail may occur. 4.9 Burning Rate: 4.4 mm/min. -

Determination of Formic Acid in Acetic Acid for Industrial Use by Agilent 7820A GC

Determination of Formic Acid in Acetic Acid for Industrial Use by Agilent 7820A GC Application Brief Wenmin Liu, Chunxiao Wang HPI With rising prices of crude oil and a future shortage of oil and gas resources, people Highlights are relying on the development of the coal chemical industry. • The Agilent 7820A GC coupled with Acetic acid is an important intermediate in coal chemical synthesis. It is used in the a µTCD provides a simple method production of polyethylene, cellulose acetate, and polyvinyl, as well as synthetic for analysis of formic acid in acetic fibres and fabrics. The production of acetic acid will remain high over the next three acid. years. In China, it is estimated that the production capacity of alcohol-to-acetic acid would be 730,000 tons per year in 2010. • ALS and EPC ensure good repeata- biltiy and ease of use which makes The purity of acetic acid determinates the quality of the final synthetic products. the 7820GC appropriate for routine Formic acid is one of the main impurities in acetic acid. Many analytical methods for analysis in QA/QC labs. the analysis of formic acid in acetic acid have been developed using gas chromatog- • Using a capillary column as the ana- raphy. For example, in the GB/T 1628.5-2000 method, packed column and manual lytical column ensures better sepa- sample injection is used with poor separation and repeatability which impacts the ration of formic acid in acetic acid quantification of formic acid. compared to the China GB method. In this application brief, a new analytical method was developed on a new Agilent GC platform, the Agilent 7820A GC System. -

Lowtemperature Chemoselective Goldsurfacemediated

DOI: 10.1002/cctc.201200311 Low-Temperature Chemoselective Gold-Surface-Mediated Hydrogenation of Acetone and Propionaldehyde Ming Pan,[a] Zachary D. Pozun,[b] Adrian J. Brush,[a] Graeme Henkelman,[b] and C. Buddie Mullins*[a] Since nanoscale gold was first discovered to be catalytically First, the hydrogenation of acetone was investigated on active,[1] gold-based catalysts have been studied both theoreti- a Au(111) surface. In a control experiment (Figure 1a), 1.62 ML cally[2] and experimentally[3] in a wide range of reactions.[4] (ML= monolayer) of acetone (m/z=43, the most-abundant These catalysts exhibit high activity for hydrogenation process- mass fragment of acetone) was adsorbed onto a clean Au(111) es,[5] in particular showing enhanced selectivity.[6] However, there is a lack of relevant fundamental studies into these pro- cesses. Conducting hydrogenation reactions on model gold surfaces is useful for obtaining mechanistic insight and for fur- ther enhancing our understanding of the catalytic properties of supported-gold catalysts. Herein, we report the chemoselec- tive hydrogenation of aldehydes over ketones on gold surfaces. The hydrogenation chemistry of oxygenated hydrocarbons has been studied on transition-metal surfaces for a variety of reactions that are important to the pharmaceutical- and chemi- cal industries.[7] For example, C=O bond hydrogenation is a key step in the catalytic conversion of cellulosic biomass.[8] In addi- tion, gold-based catalysts have also shown exceptional activity for the selective hydrogenation of a,b-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.[9] Claus found that, in the production of allyl alco- hol from the hydrogenation of acrolein, gold catalysts yielded about 10-times-higher selectivity for C=O bond hydrogenation than traditional platinum-based catalysts.[10] Therefore, explor- ing the individual reactivity of carbonyl-hydrogenation could provide useful information for a better holistic understanding of these important catalytic reactions. -

Kinetics of Oxidation of Formaldehyde, Acetaldehyde, Propionaldehyde & Butyraldehyde by Ditelluratocuprate(III) in Alkaline Medium

r Jndlan Journal of Chemistry Vol. 17A, January 1979,pp. 48·51 Kinetics of Oxidation of Formaldehyde, Acetaldehyde, Propionaldehyde & Butyraldehyde by Ditelluratocuprate(III) in Alkaline Medium C. P. MURTHY, B. SETHURAM & T. NAVANEETH RAO· Department of Chemistry, Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Received 8 June 1978; accepted 25 July 1978 Kinetics of oxidation oJ formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, proplonaldehyde and n-butyraldehyde by potasstum ditelluratocuprate(III) has been studied in alkaline medium spectrophoto- :metrically. The order in [aldeh;de] and [Cu(III)) are found to be one each and rates decreased with increase in [tellurate] and increase in [OH-]. There is no effect of addition of salts like Na, SO. and KNOa• The products of oxidation are identified as corresponding carboxylic acids. Under the experimental conditions the :monotelluratocuprate(III) species is assu:med as the active species. The ther:modynamic para:meters are also reported and a plausible mechanism has been suggested. SE of Cu(III) as an oxidizing agent is well corrections made for any self-decomposition of known in analytical chemistry in the estimation Cu (III) during the reaction. U of sugars-, glycerols-, amino acids", proteinss, carboxylic acids", carbonyl compounds" and alcohols? Results The presence of Cu(III) as intermediate was also Under the conditions [Cu(III)] ~ [aldehyde] the reported in some Cu(II)-catalysed oxidation reactions plots of log (absorbance) versus time were linear by peroxydisulphate" and vanadium (V)9. The kine- (Fig. lA), indicating the order in [Cu(III)J to be tics of decomposition and formation of Cu(III) unity. From the slopes of the above plots the diperiodate and ditellurate complexes were also pseudo-first order rate constants (k') were evaluated. -

Chemical Compatibility Chart X

Chemical Compatibility Chart Below is a chart adapted from the CRC Laboratory Handbook, which groups various chemicals in to 23 groups with examples and incompatible chemical groups. This chart is by no means complete but it will aid in making decisions about storage. For more complete information please refer to the MSDS for the specific chemical. Examples of each group can be found on the next pages. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Monomers Polymerizable Esters Alcohols, Glycols, Glycol Ether Amines and Alkanolamines Halogenated Compounds Aldehydes Acetaldehyde Saturated Hydrocar Aromatic Hydrocarbons Acid Anhydrides Alkylene Oxides Inorganic Acids Petrolium Oils Organic Acids Cyanohydrins Phosphorus Ammonia Group Halogens Ketones Caustics Phenols Nitriles Olefins Ethers Number/Chemical Esters Type bons Inorganic 1 x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x Acids 2 Organic Acids x x x x x x x x x x 3 Caustics x x x x x x x x x x x x x Amines and 4 x x x x x x x x x x x x Alkanolamines Halogenated 5 x x x x x x Compounds Alcohols, 6 Glycols, Glycol x x x x x x Ether Aldehydes 7 x x x x x x x x x x x x Acetaldehyde 8 Ketones x x x x x x Saturated 9 x Hydrocarbons Aromatic 10 x x Hydrocarbons 11 Olefins x x x 12 Petrolium Oils x 13 Esters x x x x x Monomers 14 Polymerizable x x x x x x x x x x x x Esters 15 Phenols x x x x x x x Alkylene 16 x x x x x x x x x x x x Oxides 17 Cyanohydrins x x x x x x x x x 18 Nitriles x x x x x x 19 Ammonia x x x x x x x x x x x 20 Halogens x x x x x x x x x x x x x x 21 Ethers x x x 22 Phosphorus x x x x Acid 23 x x x x x x x x x x Anhydrides X - Indicates chemicals that are incompatible and should not be stored together. -

Propionaldehyde

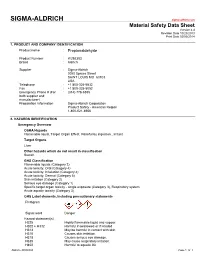

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 4.4 Revision Date 10/23/2013 Print Date 02/05/2014 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : Propionaldehyde Product Number : W292303 Brand : Aldrich Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards Flammable liquid, Target Organ Effect, Harmful by ingestion., Irritant Target Organs Liver Other hazards which do not result in classification Stench. GHS Classification Flammable liquids (Category 2) Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 4) Acute toxicity, Inhalation (Category 4) Acute toxicity, Dermal (Category 5) Skin irritation (Category 2) Serious eye damage (Category 1) Specific target organ toxicity - single exposure (Category 3), Respiratory system Acute aquatic toxicity (Category 3) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H225 Highly flammable liquid and vapour. H302 + H332 Harmful if swallowed or if inhaled H313 May be harmful in contact with skin. H315 Causes skin irritation. H318 Causes serious eye damage. H335 May cause respiratory irritation. H402 Harmful to aquatic life. Aldrich - W292303 Page 1 of 7 Precautionary statement(s) P210 Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. - No smoking. P261 Avoid breathing dust/ fume/ gas/ mist/ vapours/ spray. P280 Wear protective gloves/ eye protection/ face protection. P305 + P351 + P338 IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. -

Ester Synthesis Lab (Student Handout)

Name: ________________________ Lab Partner: ____________________ Date: __________________________ Class Period: ____________________ Ester Synthesis Lab (Student Handout) Lab Report Components: The following must be included in your lab book in order to receive full credit. 1. Purpose 2. Hypothesis 3. Procedure 4. Observation/Data Table 5. Results 6. Mechanism (In class) 7. Conclusion Introduction The compounds you will be making are also naturally occurring compounds; the chemical structure of these compounds is already known from other investigations. Esters are organic molecules of the general form: where R1 and R2 are any carbon chain. Esters are unique in that they often have strong, pleasant odors. As such, they are often used in fragrances, and many artificial flavorings are in fact esters. Esters are produced by the reaction between alcohols and carboxylic acids. For example, reacting ethanol with acetic acid to give ethyl acetate is shown below. + → + In the case of ethyl acetate, R1 is a CH3 group and R2 is a CH3CH2 group. Naming esters systematically requires naming the functional groups on both sides of the bridging oxygen. In the example above, the right side of the ester as shown is a CH3CH2 1 group, or ethyl group. The left side is CH3C=O, or acetate. The name of the ester is therefore ethyl acetate. Deriving the names of the side from the carboxylic acid merely requires replacing the suffix –ic with –ate. Materials • Alcohol • Carboxylic Acid o 1 o A o 2 o B o 3 o C o 4 Observation Parameters: • Record the combination of carboxylic acid and alcohol • Observe each reactant • Observe each product Procedure 1. -

Supplement of Investigation of Secondary Formation of Formic Acid: Urban Environment Vs

Supplement of Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., 14, 24863–24914, 2014 http://www.atmos-chem-phys-discuss.net/14/24863/2014/ doi:10.5194/acpd-14-24863-2014-supplement © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Supplement of Investigation of secondary formation of formic acid: urban environment vs. oil and gas producing region B. Yuan et al. Correspondence to: B. Yuan ([email protected]) 31 Table S1. Comparisons of measured and modeled formic acid in previous studies. Studies Location and time Model Notes Atlantic Ocean 1 MOGUNTIA Model results are 8 times lower than observations. (1996.10-11) Amazonia, Congo, Model underestimates HCOOH both in free 2 MOGUNTIA Virginia troposphere and boundary layer. Marine air, and MATCH- Measurements are underestimated by a factor of 2 or 3 those in Poisson et MPIC more, except in Amazon. al. MATCH- Measured concentrations are substantially higher than 4 Kitt Peak, US MPIC the model-calculated values. Model underestimates HCOOH compared to 5 Various sites IMPACT observations at most sites. Various sites Sources of formic acid may be up to 50% greater than 6 (MILAGRO, GEOS-Chem the estimates and the study reports evidence of a long- INTEX-B) lived missing secondary source of formic acid. Model underestimates HCOOH concentrations by up Trajectory to a factor of 2. The missing sources are considered to model with 7 North Sea (2010.3) be both primary emissions of HCOOH of MCM V3.2 & anthropogenic origin and a lack of precursor CRI emissions, e.g. isoprene. The globally source of formic acid (100-120 Tg) is 2-3 Satellite times more than that estimated from known sources.