Developing a Risk Framework for Translation Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CMMN Modeling of the Risk Management Process Extended Abstract

CMMN modeling of the risk management process Extended abstract Tiago Barros Ferreira Instituto Superior Técnico [email protected] ABSTRACT Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is thus a very important activity to support the Risk management is a development activity and achievement of the organizations' goals. increasingly plays a crucial role in Risk management is defined as “coordinated organization´s management. Being very activities to direct and control an organization valuable for organizations, they develop and with regard to risk” [1]. ERM, as a risk implement enterprise risk management management activity, comprises the strategies that improve their business model identification of the potential events in the whole and bring them better results. Enterprise risk organization that can affect the objectives, the management strategies are based on the respective risk appetite, and thus, with implementation of a risk management process reasonable assurance, the fulfillment of the and supporting structure. Together, this process organization's goals [2]. and structure form a framework. ISO 31000 Many organizations nowadays have their standard is currently the main global reference risk management framework, including framework for risk management, proposing the activities to identify their risks, and their general principles and guidelines for risk prevention measures, documented. To this end, management, regardless of context. The most [1] is at this moment the main reference for risk recent revision of the standard ISO 31000:2018 management frameworks, proposing the [1] depicts the process of risk management as general principles and guidelines for risk a case rather than a sequential process. To that management, regardless of their context. -

Deliverable D7.5: Standards and Methodologies Big Data Guidance

Project acronym: BYTE Project title: Big data roadmap and cross-disciplinarY community for addressing socieTal Externalities Grant number: 619551 Programme: Seventh Framework Programme for ICT Objective: ICT-2013.4.2 Scalable data analytics Contract type: Co-ordination and Support Action Start date of project: 01 March 2014 Duration: 36 months Website: www.byte-project.eu Deliverable D7.5: Standards and methodologies big data guidance Author(s): Jarl Magnusson, DNV GL AS Erik Stensrud, DNV GL AS Tore Hartvigsen, DNV GL AS Lorenzo Bigagli, National Research Council of Italy Dissemination level: Public Deliverable type: Final Version: 1.1 Submission date: 26 July 2017 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Task 7.5 Description ............................................................................................................... 3 Executive summary ..................................................................................................................... 4 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 2 Big Data Standards Organizations ...................................................................................... 6 3 Big Data Standards ............................................................................................................. 8 4 Big Data Quality Standards ............................................................................................. -

A Quick Guide to Responsive Web Development Using Bootstrap 3

STEP BY STEP BOOTSTRAP 3: A QUICK GUIDE TO RESPONSIVE WEB DEVELOPMENT USING BOOTSTRAP 3 Author: Riwanto Megosinarso Number of Pages: 236 pages Published Date: 22 May 2014 Publisher: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform Publication Country: United States Language: English ISBN: 9781499655629 DOWNLOAD: STEP BY STEP BOOTSTRAP 3: A QUICK GUIDE TO RESPONSIVE WEB DEVELOPMENT USING BOOTSTRAP 3 Step by Step Bootstrap 3: A Quick Guide to Responsive Web Development Using Bootstrap 3 PDF Book Written by a team of noted teaching experts led by award-winning Texas-based author Dr. Today we knowthat many other factors in?uence the well- functioning of a computer system. Rossi, M. Answers to selected exercises and a list of commonly used words are provided at the back of the book. He demonstrates how the most dynamic and effective people - from CEOs to film-makers to software entrepreneurs - deploy them. The chapters in this volume illustrate how learning scientists, assessment experts, learning technologists, and domain experts can work together in an integrated effort to develop learning environments centered on challenge-based instruction, with major support from technology. This continues to be the only book that brings together all of the steps involved in communicating findings based on multivariate analysis - finding data, creating variables, estimating statistical models, calculating overall effects, organizing ideas, designing tables and charts, and writing prose - in a single volume. Step by Step Bootstrap 3: A Quick Guide to Responsive Web Development Using Bootstrap 3 Writer The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of: How Science Fiction conquered the WorldAdvance Praise ""What a treasure house is this book. -

EMSCLOUD - an Evaluative Model of Cloud Services Cloud Service Management

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277022271 EMSCLOUD - An evaluative model of cloud services cloud service management Conference Paper · May 2015 DOI: 10.1109/INTECH.2015.7173479 CITATION READS 1 146 2 authors, including: Mehran Misaghi Sociedade Educacional de Santa Catarina (… 56 PUBLICATIONS 14 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Mehran Misaghi letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 05 July 2016 Fifth international conference on Innovative Computing Technology (INTECH 2015) EMSCLOUD – An Evaluative Model of Cloud Services Cloud service management Leila Regina Techio Mehran Misaghi Post-Graduate Program in Production Engineering Post-Graduate Program in Production Engineering UNISOCIESC UNISOCIESC Joinville – SC, Brazil Joinville – SC, Brazil [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— Cloud computing is considered a paradigm both data repository. There are challenges to be overcome in technology and business. Its widespread adoption is an relation to internal and external risks related to information increasingly effective trend. However, the lack of quality metrics security area, such as virtualization, SLA (Service Level and audit of services offered in the cloud slows its use, and it Agreement), reliability, availability, privacy and integrity [2]. stimulates the increase in focused discussions with the adaptation of existing standards in management services for cloud services The benefits presented by cloud computing, such as offered. This article describes the EMSCloud, that is an Evaluative Model of Cloud Services following interoperability increased scalability, high performance, high availability and standards, risk management and audit of cloud IT services. -

Risk Management for Engineers

Risk Management for Engineers Course No: B02-013 Credit: 2 PDH Boris Shvartsberg, Ph.D., P.E., P.M.P. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 2 2. DEFINITION OF RISK. RISK PLANNING ........................................................................................... 2 2.1. RISK IDENTIFICATION .................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2. RISK ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2.3. RISK RESPONSE ........................................................................................................................................... 5 3. RISK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE (RBS)............................................................................................ 6 4. DEALING WITH RISKS AT A PROJECT LEVEL ............................................................................... 8 5. RISKS SPECIFIC TO ELECTRICAL UTILITY COMPANIES ............................................................ 9 6. CASE STUDY - RENOVATION OF MAIN STREET SUBSTATION .................................................. 10 6.1. DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................ -

International Standard Iso 19600:2014(E)

This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-918326 INTERNATIONAL ISO STANDARD 19600 First edition 2014-12-15 Compliance management systems — Guidelines Systèmes de management de la conformité — Lignes directrices Reference number ISO 19600:2014(E) © ISO 2014 This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-918326 ISO 19600:2014(E) COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO 2014 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester. ISOTel. copyright+ 41 22 749 office 01 11 Case postale 56 • CH-1211 Geneva 20 FaxWeb + www.iso.org 41 22 749 09 47 E-mail [email protected] Published in Switzerland ii © ISO 2014 – All rights reserved This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-918326 ISO 19600:2014(E) Contents Page Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................v -

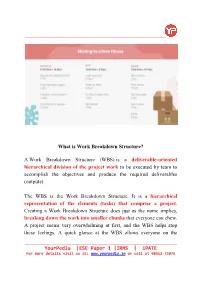

ESE Paper 1 |IRMS | Ipate What Is Work Breakdown Structure?

______________________________________________________________________________ What is Work Breakdown Structure? A Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) is a deliverable-oriented hierarchical division of the project work to be executed by team to accomplish the objectives and produce the required deliverables (outputs). The WBS is the Work Breakdown Structure. It is a hierarchical representation of the elements (tasks) that comprise a project. Creating a Work Breakdown Structure does just as the name implies, breaking down the work into smaller chunks that everyone can chew. A project seems very overwhelming at first, and the WBS helps stop these feelings. A quick glance at the WBS allows everyone on the _____________________________________________________________________________________ YourPedia |ESE Paper 1 |IRMS | iPATE For more details visit us at: www.yourpedia.in or call at 98552-73076 ______________________________________________________________________________ project team to see what has been done, and what needs to be done. The WBS is a very important part of project management for this very reason. It is prepared during the planning phase of project management. On the basis of WBS, effective project planning, execution, controlling, monitoring & reporting can be done. All the work contained within the WBS is to be identified, estimated, scheduled, and budgeted. _____________________________________________________________________________________ YourPedia |ESE Paper 1 |IRMS | iPATE For more details visit us at: www.yourpedia.in or call at 98552-73076 ______________________________________________________________________________ Work Breakdown Structure Diagram The Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) is developed to establish a common understanding of project scope. It is a hierarchical description of the work that must be done to complete the deliverables of a project. Each descending level in the WBS represents an increasingly detailed description of the project deliverables. -

Master Glossary

Master Glossary Term Definition Course Appearances 12-Factor App Design A methodology for building modern, scalable, maintainable software-as-a-service Continuous Delivery applications. Architecture 2-Factor or 2-Step Two-Factor Authentication, also known as 2FA or TFA or Two-Step Authentication is DevSecOps Engineering Authentication when a user provides two authentication factors; usually firstly a password and then a second layer of verification such as a code texted to their device, shared secret, physical token or biometrics. A/B Testing Deploy different versions of an EUT to different customers and let the customer Continuous Delivery feedback determine which is best. Architecture A3 Problem Solving A structured problem-solving approach that uses a lean tool called the A3 DevOps Foundation Problem-Solving Report. The term "A3" represents the paper size historically used for the report (a size roughly equivalent to 11" x 17"). Acceptance of a The "A" in the Magic Equation that represents acceptance by stakeholders. DevOps Leader Solution Access Management Granting an authenticated identity access to an authorized resource (e.g., data, DevSecOps Engineering service, environment) based on defined criteria (e.g., a mapped role), while preventing an unauthorized identity access to a resource. Access Provisioning Access provisioning is the process of coordinating the creation of user accounts, e-mail DevSecOps Engineering authorizations in the form of rules and roles, and other tasks such as provisioning of physical resources associated with enabling new users to systems or environments. Administration Testing The purpose of the test is to determine if an End User Test (EUT) is able to process Continuous Delivery administration tasks as expected. -

OWASP Top 10 - 2017 the Ten Most Critical Web Application Security Risks

OWASP Top 10 - 2017 The Ten Most Critical Web Application Security Risks This work is licensed under a https://owasp.org Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License 1 TOC Table of Contents Table of Contents About OWASP The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) is an TOC - About OWASP ……………………………… 1 open community dedicated to enabling organizations to FW - Foreword …………..………………...……… 2 develop, purchase, and maintain applications and APIs that can be trusted. I - Introduction ………..……………….……..… 3 At OWASP, you'll find free and open: RN - Release Notes …………..………….…..….. 4 • Application security tools and standards. Risk - Application Security Risks …………….…… 5 • Complete books on application security testing, secure code development, and secure code review. T10 - OWASP Top 10 Application Security • Presentations and videos. Risks – 2017 …………..……….....….…… 6 • Cheat sheets on many common topics. • Standard security controls and libraries. A1:2017 - Injection …….………..……………………… 7 • Local chapters worldwide. A2:2017 - Broken Authentication ……………………... 8 • Cutting edge research. • Extensive conferences worldwide. A3:2017 - Sensitive Data Exposure ………………….. 9 • Mailing lists. A4:2017 - XML External Entities (XXE) ……………... 10 Learn more at: https://www.owasp.org. A5:2017 - Broken Access Control ……………...…….. 11 All OWASP tools, documents, videos, presentations, and A6:2017 - Security Misconfiguration ………………….. 12 chapters are free and open to anyone interested in improving application security. A7:2017 - Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) ….…………….. 13 We advocate approaching application security as a people, A8:2017 - Insecure Deserialization …………………… 14 process, and technology problem, because the most A9:2017 - Using Components with Known effective approaches to application security require Vulnerabilities .……………………………… 15 improvements in these areas. A10:2017 - Insufficient Logging & Monitoring….…..….. 16 OWASP is a new kind of organization. -

A Risk Breakdown Structure for Public Sector Construction Projects

A Risk Breakdown Structure for Public Sector Construction Projects Marie Dalton Centre for Research in the Management of Projects, Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester (email: [email protected]) Abstract This research is part of a wider project (ProRIde) focusing on the risk identification stage of the risk management process. The specific remit of the study is to analyse the text of National Audit Office (NAO) reports to identify recurring risk sources on public sector construction projects. A textual analysis software, QSR N6, is used to code the data. The risk source information in organised and presented in a Risk Breakdown Structure (RBS), a hierarchical presentation of risk sources. The output of this study represents a contribution to knowledge in that it is empirically derived – many risk identification support tools are compiled on an ad•hoc basis through brainstorming or personal experience. This research takes advantage of a rich existing database and employs a systematic methodology to develop an RBS that is specific to the context of public sector construction projects. Keywords: Public sector procurement, construction, risk identification, risk breakdown structures, QSR N6 1. Introduction 1.1 Overview of the ProRIde project ProRIde (Project Risk Identification) is an EPSRC•funded project (GR/R51452) concerned specifically with the risk identification phase of the risk management process (see Figure 1). Concurrent studies within the ProRIde project examine risk identification by individual project managers [1] and work is starting on group dynamics. Comprehensive risk identification is central to the relevance and effectiveness of the subsequent risk management process [2] • unidentified risk sources remain as unknown and unmanaged threats to the project objectives. -

Development Project Management

DEVELOPMENT PROJECT MANAGEMENT Project Management Associate (PMA) Certification Learning Guide 2016 GUIDE PM4R: PROJECT MANAGEMENT FOR RESULTS Página 0 AUTHORS Rodolfo Siles, PMP, and Ernesto Mondelo, PMP. TECHNICAL REVISION Harald Modis, PMP; Galileo Solís, PMP; John Cropper, Prince2; Victoria Galeano, PMP, and Roberto Toledo, PMP. FOURTH EDITION UPDATE 2015 Ricardo Sánchez Orduña, PMP. IDB COLLABORATORS Matilde Neret; Carolina Aclan; Nydia Díaz; Rafael Millan; Juan Carlos Sánchez; Jorge Quinteros; Roberto García; Beatriz Jellinek; Eugenio Hillman; Masami Yamamori; Víctor Shiguiyama; Juan Manuel Leano; Gabriel Nagy, PMP; Samantha Pérez; Cynthia Smith, and Pablo Rolando. SPECIAL RECOGNITION To the team members that contributed to the validation of the course contents and methodology. Paraguay Ada Verna, Adilio Celle, Alcides Moreno, Álvaro Carrón, Amado Rivas, Amilcar Cazal, Carmiña Fernández, Carolina Centurión, Carolina Vera, Cesar David Rodas, Daniel Bogado, Diana Alarcón, Eduardo Feliciangeli, Félix Carballo, Fernando Santander, Gloria Rojas, Gonzalo Muñoz, Hernán Benítez, Hugo García, Ignacio Correa, Joaquín Núñez, Jorge Oyamada, Jorge Vergara, José Demichelis, Juan Jacquet, Laura Santander, Lourdes Casanello, Luz Cáceres, Mabel Abadiez, Malvina Duarte, Mariano Perales, Marta Corvalán, Marta Duarte, Nelson Figueredo, Nilson Román, Noel Teodoro, Nohora Alvarado, Norma López, Norma Ríos, Oscar Charotti, Patricia Ruiz, Reinaldo Peralta, Roberto Bogado, Roberto Camblor, Rocío González, Simón Zalimben, and Sonia Suárez. Bolivia Alex Saldías, Amelia López, Ana Meneses, Boris Gonzáles, Christian Lündstedt, Debbie Morales, Edgar Orellana, Fernando Portugal, Francisco Zegarra, Freddy Acebey, Freddy Gómez, Gabriela Sandi, Georgia Peláez, Gilberto Moncada, Gina Peñaranda, Gonzalo Huaylla, Hugo Weisser, Iván Iporre, Jorge Cossio, Joyce Elliot, Karin Daza, Leticia Flores, Luis Yujra, Marcelino Aliaga, Margarita Ticona, María Fernanda Padrón, Mónica Sanabria, Nicolás Catacora, Rommy Verástegui, Rossana Fernández, Rossina Alba, Salvador Torrico, and Santiago Rendón. -

Uncovering All of the Risks on Your Projects Vol

PM World Journal Uncovering All Of The Risks On Your Projects Vol. V, Issue IX – September 2016 by Paul Burek, PMP, CSM www.pmworldjournal.net Second Edition Uncovering All Of The Risks On Your Projects1 Paul Burek, PMP, CSM Solutions Cube Group LLC Abstract Through my experience working with project teams, in many industries, on hundreds of projects, I have learned that although Project Managers (PMs) are expected to manage risk on their projects, many times they end up fighting fires and managing the problems that result from unmanaged or unknown risks. There are many reasons why Project Managers avoid Risk Management and resort to firefighting project problems. Common perceptions PMs have are: My project won’t hurt anybody Our company has a “kill the messenger” syndrome, so it is best not to bring up risks Firefighting is rewarded, the more problems I can solve, the better I look Failure is not an option, so why focus on risks, our team won’t allow them to impact the project Risk is inevitable, so why bother trying to avoid or manage it. Another underlying reason for not managing risk on projects, or not managing it well, is because the Project Manager does not have the right tools and techniques for risk management. It all too common for PMs to understand risk management theory, but not be skilled in the transformation of this theory into practical application. Effective risk management includes engaging the project stakeholders throughout the entire risk management process: identifying, assessing, responding to and managing risks throughout the life of the project.