Literary Trends 2017 B5.139

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dušan Šarotar, Born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, Is a Writer, Poet and Screenwri- [email protected] Ter

Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. He studied Sociology of Culture and www.zalozba.org Philosophy at the University of Ljublja- www.readcentral.org na. He has published two novels (Island of the Dead in 1999 and Billiards at the Translation: Gregor Timothy Čeh Dušan Šarotar Hotel Dobray in 2007), three collecti- ons of short stories (Blind Spot, 2002, Editor: Renata Zamida Author’s Catalogue Layout: designstein.si Bed and Breakfast, 2003 and Nostalgia, Photo: Jože Suhadolnik, Dušan Šarotar 2010) and three poetry collections (Feel Proof-reading: Catherine Fowler, for the Wind, 2004, Landscape in Minor, Marianne Cahill 2006 and The House of My Son, 2009). Ša- rotar also writes puppet theatre plays Published by Beletrina Academic Press© and is author of fifteen screenplays for Ljubljana, 2012 documentary and feature films, mostly for television. The author’s poetry and This publication was published with prose have been included into several support of the Slovene Book Agency: anthologies and translated into Hunga- rian, Russian, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Czech and English. In 2008, the novel Billiards at the Hotel Dobray was nomi- nated for the national Novel of the Year Award. There will be a feature film ba- ISBN 978-961-242-471-8 sed on this novel filmed in 2013. Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. -

TOTAL of 10 PACES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL Of 10 PACES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED Charles Olson and the (Post)Modem Episteme by 0 David Baird A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department ofEnglish Memorial University ofNewfoundland April2004 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Bibliotheque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 0-612-99049-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 0-612-99049-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I' Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits meraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni Ia these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Fall 2011 / Winter 2012 Dalkey Archive Press

FALL 2011 / WINTER 2012 DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS CHAMPAIGN - LONDON - DUBLIN RECIPIENT OF THE 2010 SANDROF LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT Award FROM THE NatiONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE what’s inside . 5 The Truth about Marie, Jean-Philippe Toussaint 6 The Splendor of Portugal, António Lobo Antunes 7 Barley Patch, Gerald Murnane 8 The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, Kjersti A. Skomsvold 9 The No World Concerto, A. G. Porta 10 Dukla, Andrzej Stasiuk 11 Joseph Walser’s Machine, Gonçalo M. Tavares Perfect Lives, Robert Ashley (New Foreword by Kyle Gann) 12 Best European Fiction 2012, Aleksandar Hemon, series ed. (Preface by Nicole Krauss) 13 Isle of the Dead, Gerhard Meier (Afterword by Burton Pike) 14 Minuet for Guitar, Vitomil Zupan The Galley Slave, Drago Jančar 15 Invitation to a Voyage, François Emmanuel Assisted Living, Nikanor Teratologen (Afterword by Stig Sæterbakken) 16 The Recognitions, William Gaddis (Introduction by William H. Gass) J R, William Gaddis (New Introduction by Robert Coover) 17 Fire the Bastards!, Jack Green 18 The Book of Emotions, João Almino 19 Mathématique:, Jacques Roubaud 20 Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Veteranyi (Afterword by Vincent Kling) 21 Iranian Writers Uncensored: Freedom, Democracy, and the Word in Contemporary Iran, Shiva Rahbaran Critical Dictionary of Mexican Literature (1955–2010), Christopher Domínguez Michael 22 Autoportrait, Edouard Levé 23 4:56: Poems, Carlos Fuentes Lemus (Afterword by Juan Goytisolo) 24 The Review of Contemporary Fiction: The Failure Issue, Joshua Cohen, guest ed. Available Again 25 The Family of Pascual Duarte, Camilo José Cela 26 On Elegance While Sleeping, Viscount Lascano Tegui 27 The Other City, Michal Ajvaz National Literature Series 28 Hebrew Literature Series 29 Slovenian Literature Series 30 Distribution and Sales Contact Information JEAN-PHILIPPE TOUSSAINT titles available from Dalkey Archive Press “Right now I am teaching my students a book called The Bathroom by the Belgian experimentalist Jean-Philippe Toussaint—at least I used to think he was an experimentalist. -

PİŞ Çağdaş İngiliz Şiiri Antolojisi Cevat Çapan

JÎJ - i* - PİŞ Çağdaş İngiliz Şiiri Antolojisi Cevat Çapan ADAM YAYINLARI © Adam Yayıncılık ve Matbaacılık A.Ş. Birinci Basım Ekim 1985 Çağdaş İngiliz Şiiri A ntolojisi Cevat Çapan ÖNSÖZ Bu antolojide bir araya getirdiğim otuz iki şairin yüz bir şiiri sanırım yirminci yüzyıl İngiliz şiirini bütün özellikleriyle tanıtma ya yeterli değildir. Her şeyden önce, şiir çevirisinin güçlüğü böyle bir yetkinliği engelleyen başlıca etken. Buna bir de bu işe girişen kişinin kendi sınırlılığını eklerseniz, böyle bir derlemenin eksik likleri ve fazlalıkları daha da kolay anlaşılır. Bütün bu sınırlılıkla ra karşın, Çağdaş İngiliz Şiiri Antolojisi’nde yirminci yüzyıl İngiliz şiirinin gelişme çizgisini, her şair kuşağının başlıca temsilcilerini elimden geldiğince okurlara tanıtmaya çalıştım. Amacım İngiliz Edebiyatı öğrencileri için eksiksiz bir ders kitabı hazırlamak de ğildi. Daha çok şiir severlerin ilgisini çekebilecek şiirleri çevirinin olanakları içinde sunmayı denedim. Ama bu eksiklikleriyle de edebiyat öğrencilerinin işine yarayacak bir şeyler ortaya koyabil- dimse, bundan büyük bir mutluluk duyacağımı da açıklamalıyım. Konuyla ilgilenen okurların bu antolojinin bu alanda yalnızca bir ilk adım olduğunu anlayacaklarına inanıyorum. C.Ç. 7 İKİNCİ BASKIYA ÖNSÖZ Çağdaş Ingiliz Şiiri Antolojisi'nin 1985’teki ilk baskısına yaz dığım önsözde o kitapta bir araya getirilen otuz iki şairden yapı lan çevirilerin 20. Yüzyıl İngiliz Şiiri’ni bütün özellikleriyle tanıt maya yeterli olmadığını açıklamıştım. Her antoloji gibi bunun da birçok eksikleri vardı. Geçen zaman içinde gerek benim Christop her Middleton, Andrew Motion, Michael Hulse ve Lavinia Gre- enlaw’dan, gerekse Nezih Onur, Coşkun Yerli, Gökçen Ezber ve Nazmi Ağıl’ın Basil Bunting, Henry Reed, Charles Tomlinson, Tony Harrison, Hugo Williams ve Simon Armitage’den yaptığı mız çevirilerin eklenmesiyle bu antolojinin eksikleri bir ölçüde azalmış oldu. -

The Ninth Country: Handke's Heimat and the Politics of Place

The Ninth Country: Peter Handke’s Heimat and the Politics of Place Axel Goodbody [Unpublished paper given at the conference ‘The Dynamics of Memory in the New Europe: National Memories and the European Project’, Nottingham Trent University, September 2007.] Abstract Peter Handke’s ‘Yugoslavia work’ embraces novels and plays written over the last two decades as well as his 5 controversial travelogues and provocative media interventions since the early 1990s. It comprises two principal themes: criticism of media reporting on the conflicts which accompanied the break-up of the Yugoslavian federal state, and his imagining of a mythical, utopian Slovenia, Yugoslavia and Serbia. An understanding of both is necessary in order to appreciate the reasons for his at times seemingly bizarre and perverse, and in truth sometimes misguided statements on Yugoslav politics. Handke considers it the task of the writer to distrust accepted ways of seeing the world, challenge public consensus and provide alternative images and perspectives. His biographically rooted emotional identification with Yugoslavia as a land of freedom, democratic equality and good living, contrasting with German and Austrian historical guilt, consumption and exploitation, led him to deny the right of the Slovenians to national self- determination in 1991, blame the Croatians and their international backers for the conflict in Bosnia which followed, insist that the Bosnian Serbs were not the only ones responsible for crimes against humanity, and defend Serbia and its President Slobodan Milošević during the Kosovo war at the end of the decade. My paper asks what Handke said about Yugoslavia, before going on to suggest why he said it, and consider what conclusions can be drawn about the part played by writers and intellectuals in shaping the collective memory of past events and directing collective understandings of the present. -

The Central Europe of Yuri Andrukhovych and Andrzej Stasiuk

Rewriting Europe: The Central Europe of Yuri Andrukhovych and Andrzej Stasiuk Ariko Kato Introduction When it joined the European Union in 2004, Poland’s eastern bor- der, which it shared with Ukraine and Belarus, became the easternmost border of the EU. In 2007, Poland was admitted to the Schengen Con- vention. The Polish border then became the line that effectively divided the EU identified with Europe from the “others” of Europe. In 2000, on the eve of the eastern expansion of the EU, Polish writer Andrzej Stasiuk (1960) and Ukrainian writer Yuri Andrukhovych (1960) co-authored a book titled My Europe: Two Essays on So-called Central Europe (Moja Europa: Dwa eseje o Europie zwanej Środkową). The book includes two essays on Central Europe, each written by one of the authors. Unlike Milan Kundera, who discusses Central Europe as “a kidnapped West” which is “situated geographically in the center—cul- turally in the West and politically in the East”1 in his well-known essay “A Kidnapped West, or the Tragedy of Central Europe” (“Un Occident kidnappé ou la tragédie de l’Europe centrale”) (1983),2 written in the Cold War period, they describe Central Europe neither as a corrective concept nor in terms of the binary opposition of West and East. First, as the subtitle of this book suggests, they discuss Central Europe as “my 1 Milan Kundera, “A Kidnapped West or Culture Bows Out,” Granta 11 (1984), p. 96. 2 The essay was originally published in French magazine Le Débat 27 (1983). - 91 - Ariko Kato Europe,” drawing from their individual perspectives. -

New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola

Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, Shelley Stamp New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola As part of this issue on “The System Beyond the Studios,” I sought not only to give scholars an opportunity to publish work that looks at specific cases reassessing the history of Hollywood, but I also wanted to look more broadly at the state of the field of American film history. As such, I assembled a roundtable of scholars who have been studying Hollywood through myriad lenses for most of their careers. I wanted to know, from their perspective, what were the current and future threads to be taken up in the study of this central topic in cinema and media studies. The roundtable discussion focuses on innovative methods, sources, and approaches that give us new insights into the study of Hollywood. Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, and Shelley Stamp all participated while I moderated the conversation. It was conducted via email and Google docs in the fall of 2017. Each participant began by writing a brief response to a broad question on one topic – research, methodology, pedagogy, or the meaning of ‘Hollywood.’ These responses were then culled together and given follow up questions which were all placed in a Google drive folder. Over the course of two months, the participants added responses, provocations, and questions on each of the threads, while I added follow up questions to guide the discussion. When seen as a whole, this roundtable creates a snapshot of where the field of Hollywood history is at this moment. -

An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence

379 AN ORAL INTERPRETATION SCRIPT ILLUSTRATING THE INFLUENCE ON CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POETRY OF THE THREE BLACK MOUNTAIN POETS: CHARLES OLSON, ROBERT CREELEY, ROBERT DUNCAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By H. Vance James, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1981 J r James, H. Vance, An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence on Contemporary American Poetry of the Three Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan. Master of Science (Speech Communication and Drama), August, 1981, 87 pp., bibliography, 23 titles. This oral interpretation thesis analyzes the impact that three poets from Black Mountain College had on contemporary American poetry. The study concentrates on the lives, works, poetic theories of Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Robert Duncan and culminates in a lecture recital compiled from historical data relating to Black Mountain College and to the three prominent poets. @ 1981 HAREL VANCE JAMES All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 History of Black Mountain College Purpose of the Study Procedure II. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION . 12 Introduction Charles Olson Robert Creeley Robert Duncan III. ANALYSIS . 31 IV. LECTURE RECITAL . 45 The Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan "These Days" (Olson) "The Conspiracy" (Creeley) "Come, Let Me Free Myself" (Duncan) "Thank You For Love" (Creeley) "The Door" (Creeley) "Letter 22" (Olson) "The Dance" (Duncan) "The Awakening" (Creeley) "Maximus, To Himself" (Olson) "Words" (Creeley) "Oh No" (Creeley) "The Kingfishers" (Olson) "These Days" (Olson) APPENDIX . -

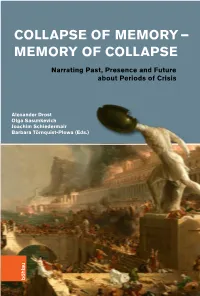

Collapse of Memory

– – COLLAPSE OF MEMORY – MEMORY OF COLLAPSE Narrating Past, Presence and Future about Periods of Crisis Alexander Drost Olga Sasunkevich Joachim Schiedermair COLLAPSE OF MEMORY OF COLLAPSE MEMORY Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (Eds.) Alexander Drost, Volha Olga Sasunkevich, Olga Sasunkevich, Alexander Drost, Volha Joachim Schiedermair, Barbara Törnquist-Plewa Joachim Schiedermair, Barbara Törnquist-Plewa Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Alexander Drost ∙ Olga Sasunkevich Joachim Schiedermair ∙ Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (Ed.) COLLAPSE OF MEMORY – MEMORY OF COLLAPSE NARRATING PAST, PRESENCE AND FUTURE ABOUT PERIODS OF CRISIS BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft aus Mitteln des Internationalen Graduiertenkollegs 1540 „Baltic Borderlands: Shifting Boundaries of Mind and Culture in the Borderlands of the Baltic Sea Region“ Published with assistance of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft by funding of the International Research Training Group “Baltic Borderlands: Shifting Boundaries of Mind and Culture in the Borderlands of the Baltic Sea Region” Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2019 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Cie, Lindenstraße 14, D-50674 Köln -

West Side Story"

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-6-2014 12:00 AM Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom: Modernist Moods of "West Side Story" Andrew M. Falcao The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Paul Coates The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Andrew M. Falcao 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Falcao, Andrew M., "Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom: Modernist Moods of "West Side Story"" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2091. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2091 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRAGEDY, ECSTASY, DOOM: MODERNIST MOODS OF “WEST SIDE STORY” (Thesis format: Monograph) by Andrew Michael Falcao Graduate Program in Global Film Cultures A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Andrew M. Falcao 2014 i Abstract This thesis looks to reposition West Side Story (Jerome Robbins/Robert Wise, 1961) as an example of (neo-)modernist art. Placing the film within its context of Hollywood musicals, I see West Side Story as a particularly rich locus in which to study the genre’s modernist impulses. -

Modernism Revisited Edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller XXXV | 2/2014

Filozofski vestnik Modernism Revisited Edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller XXXV | 2/2014 Izdaja | Published by Filozofski inštitut ZRC SAZU Institute of Philosophy at SRC SASA Ljubljana 2014 CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 141.7(082) 7.036(082) MODERNISM revisited / edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller. - Ljubljana : Filozofski inštitut ZRC SAZU = Institute of Philosophy at SRC SASA, 2014. - (Filozofski vestnik, ISSN 0353-4510 ; 2014, 2) ISBN 978-961-254-743-1 1. Erjavec, Aleš, 1951- 276483072 Contents Filozofski vestnik Modernism Revisited Volume XXXV | Number 2 | 2014 9 Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller Editorial 13 Sascha Bru The Genealogy-Complex. History Beyond the Avant-Garde Myth of Originality 29 Eva Forgács Modernism's Lost Future 47 Jožef Muhovič Modernism as the Mobilization and Critical Period of Secular Metaphysics. The Case of Fine/Plastic Art 67 Krzysztof Ziarek The Avant-Garde and the End of Art 83 Tyrus Miller The Historical Project of “Modernism”: Manfredo Tafuri’s Metahistory of the Avant-Garde 103 Miško Šuvaković Theories of Modernism. Politics of Time and Space 121 Ian McLean Modernism Without Borders 141 Peng Feng Modernism in China: Too Early and Too Late 157 Aleš Erjavec Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge 175 Patrick Flores Speculations on the “International” Via the Philippine 193 Kimmo Sarje The Rational Modernism of Sigurd Fosterus. A Nordic Interpretation 219 Ernest Ženko Ingmar Bergman’s Persona as a Modernist Example of Media Determinism 239 Rainer Winter The Politics of Aesthetics in the Work of Michelangelo Antonioni: An Analysis Following Jacques Rancière 255 Ernst van Alphen On the Possibility and Impossibility of Modernist Cinema: Péter Forgács’ Own Death 271 Terry Smith Rethinking Modernism and Modernity 321 Notes on Contributors 325 Abstracts Kazalo Filozofski vestnik Ponovno obiskani modernizem Letnik XXXV | Številka 2 | 2014 9 Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller Uvodnik 13 Sascha Bru Genealoški kompleks. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939