Muslims of Surma-Barak Valley in the Partition of 1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anaemia and Associated Factors Among the Bengali Muslims of Cachar District in Assam, India

Eurasian Journal of Anthropology Euras J Anthropol 8(1):1-12, 2017 ISSN: 2166-7411 Anaemia and associated factors among the Bengali Muslims of Cachar district in Assam, India A. F. Gulenur Islam Barbhuiya Department of Anthropology M. H. C. M. Science College, Hailakandi, Assam, India Article info Abstract Received: 3 February 2017 Present study is an effort to observe the prevalence of anaemia Accepted: 5 November 2017 with reference to age, education and income among the Bengali Muslims of Cachar District of Assam, India. The data have been collected by household census method and colour scale for haemoglobin among 362 Bengali Muslims (male-183, female-179) Key words of 15 to 79 years of age from Ganganagar Part-I and Bhaurikandi Bengali Muslims, Cachar, Anaemia, Part-II village of Cachar District. The study reveals that half Age, Education, Income. (50.0%) of the adult Bengali Muslim population is prone to different grades of anaemia. 20.7% of them are found to have mild anaemia; but a major proportion (27.1%) of them are For correspondence suffering from moderate anaemia and 2.2% of them are found to be severely anaemic. Prevalence of anaemia is found to be Gulenur Islam Barbhuiya significantly high (p-0.001) among the Bengali Muslim females (60.3%) compared to their male counterparts (39.9%). Anaemia is Moinul Hoque Choudhury Memorial Science College, Hailakandi, found to be more prevalent in older age groups in comparison to Assam, India. younger age groups of the community. Prevalence of anaemia decreases with the increase of educational status and per capita monthly income in the community. -

Moinul Hoque Choudhury Memorial Science College Moinul Hoque Choudhury Memorial Science College

Moinul Hoque Choudhury Memorial Science College Moinul Hoque Choudhury Memorial Science College About Moinul Hoque Choudhury Moinul Hoque Choudhury was born on 13 May 1923 in a well known family of Sonabarighat in Cachar district of Assam. He was born to mother Mona Bibi and father Montajir Ali. Choudhury took his primary education from M.E. School of Sonabraighat. He passed Matriculation from Silchar Government H.S. School and later joined Cotton College, Guwahati/Murari Chand College of Sylhet and passed intermediate in 1942. He graduated with History Honours from Presidency College of Kolkata in 1944. In the Presidency, he defeated Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in the college election. He pursued M.A. in History securing first class first position from Aligarh Muslim University in 1946. He also took part in the Indian independence movement. In 1947, he obtained LLB from Aligarh Muslim University. Inspired by the ideas of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Moulana Abul Kalam Azad, Hoque joined the freedom struggle. Following India’s independence and the partition of India, he joined Indian National Congress under the influence of Fakaruddin Ali Ahmed. To start his career, Moinul Hoque Choudhury joined the Bar Association of Silchar in 1948 and later in 1950, he joined active politics as a member of local board in 1950 and was a nominated member of Silchar Municipality in the same year. He became a member of Assam Legislative Assembly in 1952 from East Sonai constituency. Moinul Hoque became a cabinet minister (agriculture) in 1957 after being elected for the second time from the same constituency. -

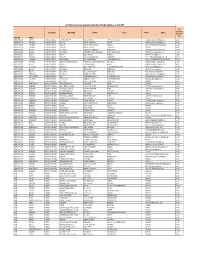

Wef April 2015 to March 2016

1 Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 (w.e.f. April 2015 to March 2016) Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration Vill.-Khairani, P.O.-Chachepani, P.S.-Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 6-4-2015 BAK/260/H/01 OF 2015-16 Bishnujyoti N.G.O. Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781360. 6-4-2015 BAK/260/H/02 OF 2015-16 Nawa Dahar N.G.O. Vill.-Kahibari, P.O.-Orangpara, Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa 6-4-2015 BAK/260/H/03 OF 2015-16 Udayan Vill.& P.O.-Kepavitha, Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Baksa H.O.-Bhakuamary, P.O.-Ananda Bajar, P.S.-Salbari, Dist.- 6-4-2015 BAK/260/H/04 OF 2015-16 Friendship N.G.O. Baksa Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Vill.-Jhargaon, P.O.-Sobankhata, P.S.-Barbari, Dist.-Baksa 10-4-2015 BAK/260/H/05 OF 2015-16 Jhargaon Vill. Development Committee Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Vill.-Motipur, Kolachowk, P.O.-Motipur, P.S.-Tamulpur,Dist.- 10-4-2015 BAK/260/H/06 OF 2015-16 Jwogafu N.G.O. Baksa Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781372. Vill.-Baganpara (Mainaosali), P.O.-Baganpara,P.S.-Barbori. 10-4-2015 BAK/260/H/07 OF 2015-16 Baganpara Mainaosali Aijw Afad Baksa Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Vill.-Dakhinkuchi (Satgaon), P.O.-Subankhata,P.S.-Barbari, 10-4-2015 BAK/260/H/08 OF 2015-16 Satgaon Jougafu Afad Baksa Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Vill.-Maithabari (Bhawraguri), P.O.-Subankhata, P.S.- 10-4-2015 BAK/260/H/09 OF 2015-16 Bhawraguri Development Committee Baksa Barbari, Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam. -

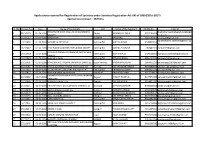

Applications Received for Registration of Societies (2016-2017).Pdf

Applications received for Registration of Societies under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 (2016-2017) Applications recieved = 4209 Nos. Sl. No. Receipt No. Date Name of the Society Dist Name of the Applicant Mobile No. Email ID JHAGRAPAR NAVA KALLYAN DEVELOPMENT jhagrarparnavakallyandvsociety@g 1 08210379 01-04-2016 Dhubri ASHRAFUL HOQUE 9957186659 SOCIETY mail.com 2 12210127 01-04-2016 SOROIWATI Golaghat RAJIB DAS 9859769391 [email protected] [email protected] 3 15211430 01-04-2016 SURAKSHA INITIATIVE Kamrup (M) AMIT SHARMA 9508817613 m 4 15211447 01-04-2016 DHALBOMA SMASHAN PARISALANA SAMITY Kamrup (M) SUBHAS TUMUNG 967882322 [email protected] SRI SRI DAKSHINA KALI MANDIR PARISALANA 5 15211448 01-04-2016 Kamrup (M) DILIP TAMULI 9435116097 [email protected] SAMITY 6 15211449 01-04-2016 WAS BIPU CLUB Kamrup (M) BITUPAN RANGI 8486165594 [email protected] 7 30210001 01-04-2016 MANDIRA N.C. KRISHAK UNNAYAN SAMITTEE South Kamrup ANOWAR HUSSAIN 9864072234 [email protected] 8 06210182 02-04-2016 DHULA ANCHALIK KRISAK JYOTI SAMITTEE Darrang MAHIRUDDIN AHMED 9859586820 [email protected] 9 15211450 02-04-2016 YOUNG PEOPLE WELFARE FOUNDATION Kamrup (M) PRANAB KR SAIKIA 9864412276 [email protected] 10 19210437 02-04-2016 RAMAKRISHNA SEVASHRAM Kokrajhar PRADIP KR SAHA 9957724665 [email protected] DABAKA PATHER AMORJYOTI YUBA UNNAYAN 11 22210668 02-04-2016 Nagaon ANWAR HUSSAIN 8724871287 [email protected] PARISHAD 12 22210669 02-04-2016 ROYAL FOUNDATION Nagaon RAIHAN UDDIN 8724871287 [email protected] -

Annual Report 2019-2020

Indian Council of Social Science Research North-Eastern Regional Centre Forty-Third Annual Report ICSSR-NERC 2019-2020 Printed at : Modern Off set, Wahthapbroo, Shillong - 2, Meghalaya, : 0364-2243437, E-mail : modernoff [email protected] ii Annual Report - 2019-2020 CONTENTS Chapter Page No. Foreword .................................................................................................................................................. v Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1-2 1. Seminars, Workshops, Conferences ................................................................................... 3 - 98 1.1 Seminars sponsored by the NERC ........................................................................................ 3 1.2 Seminars organized by the NERC ...................................................................................... 97 2. Services Rendered to Scholars ..........................................................................................98-102 2.1 Study Grant ..............................................................................................................................98 2.2 Contingency Grant for Doctoral Scholars ........................................................................99 2.3 Research Projects ................................................................................................................. 101 3. Lectures .............................................................................................................................................. -

Final & Master.Pmd

Souvenir & Book of Abstracts Detailed Programme Schedule ICSSR Sponsored National Seminar On “Ethnicity, Identity and Politics: Quest for Peace and Development” 1st and 2nd November, 2019 Organised by Department of Political Science Date - November 1, 2019 (Day: 1) Time: 9.00 am to 10.00 am : Registration 10.00 am to 11.30 am : Inaugural Session Welcome Address : Dr. Devabrot Khanikor Principal, Sonapur College Inaugurator : Prof. Pratap Jyoti Handique Vice Chancellor, Gauhati University Speech : Dr. Jit Ram Dutta, President, Governing Body Sonapur College Guest of Honor : Prof. Dilip Kr. Kalita, Director, Anundoram Borooah Institute of Language, Art & Culture Keynote Speaker : Prof. Akhil Ranjan Dutta, HOD, Department of Political Science, Gauhati University Theme Ethnicity and Identity in the Age of Neo-Liberal Globalization: Reflection on India’s North-East Time :11.30 am to 11.45am : Tea Break Room-Theatre Hall Time - 11.45to 12.45 : Plenary Session Speaker : Dr. Sanjay Borbora, Associate Professor, Tata Institute of Social Science, Guwahati Theme: “How ‘Ethnic’ are the conflicts in North East India”. Time: 12.45 pm to 1.30 pm : Lunch Break Technical Sessions Date: 1-11-2019 : Room - Hall – A Time: 1.30 pm to 3.30 pm : Technical Session-1 Theme: Ethnicity, Folklore and Folklife Chairperson : Dr. Pallabi Borah, Assistant professor, Department of Folklore Research, Gauhati University 18 National Seminar Souvenir & Book of Abstracts Papers:- Suppressed Voices: Narratives from the North East Dr. Bhuban Chandra Talukdar Assistant Professor of English Handique Girls’ College, Ghy-1 e-mail: [email protected] mob.7002383537 Musings from the Past: Locating Identity and Belongingness in Sujit Choudhury’s“ Harano Din Harano Manush”. -

Madrassas of Surma-Barak Valley in Partition

Chapter – V MADRASSAS OF SURMA-BARAK VALLEY IN PARTITION India attained her freedom at a great cost. The British ruled the country for about two centuries but left dividing the country in to two independent dominions, India and Pakistan. The debate on partition and its inevitability, as entailed by scholars across the subcontinent, has remained inconclusive even to this day. There is still no answer as to whether partition was really inevitable or there was an alternative. Nevertheless, the fact which is most relevant here is that India was partitioned and Pakistan was created. When the rest of the country, observing the situation and looking at it from various angles, was either supporting the partition or protesting against the same, the Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten announced his 3rd June Plan which was implemented with the partition of Punjab, Bengal and Assam. A new nation appeared in the world map – created by political leaders in the name of religion. An interesting point of observation here is that though Pakistan was created in the name of religion, religious leaders were initially mush against the plan of partition. In the last three decades of the freedom movement, most of the politically conscious Ulemas of India were somewhat connected with Dar-ul-Ulum Deoband or with a Deobandi Madrassa or otherwise with its political wing Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind. However, Mr. Jinnah with his able political maneuvers became instrumental in the creation of Pakistan. He managed to gain the support of a number of Ulemas and very tactfully utilized them in mobilizing the masses in the favour of partition and in the creation of Pakistan. -

List of Business Correspondent Agents Under Kiosk Banking Solution As on 30-12-2017

List of Business Correspondent agents under Kiosk Banking Solution as on 30-12-2017 Last Remuneration CIRCLE OFFICE BRANCH NAME BCA Name VILLAGE CONTACT EMAIL-ID given to Bank Mitra STATE NAME DISTRICT ANDHRA PRADESH GUNTUR ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) GUNTUR ARUNDULPET PADMAJA MANTHRI GUNTER M AND CORP OG 7356359659 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH PRAKASAM ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) PALUKURU KONDURI SAIRAMIREDDY PALUKUR 8184860218 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH PRAKASAM ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) EDARA (AP) OGURURI LAKSHMI RAMADEVI PURIMETLA 8186813346 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH PRAKASAM ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) EDARA (AP) KONDAVEETI SRIDEVI VEMULABANDA 8187058876 Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH NELLORE ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) BASINENIPALLI PRASANNA KUMAR AMILIPOGU BASINENIPALLE 8331817440 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH NELLORE ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) BASINENIPALLI MUTTAMSETTY CHENNNAKRISHNAIAH DEVARAJUSURAYAPALLE 8500560327 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH NELLORE ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) MOPURU MAHESH MANCHA PALUGODU 9010106610 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH PRAKASAM ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) EDARA (AP) NAGUMALLI CHINA ANKAMMA KOMMAVARAM 9010514740 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH VIZIANAGRAM ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) VINAYAKA NAGAR DHILLI PRABHAKARARAO VIZIANAGARAM (M AND OG) 9440033761 [email protected] Dec-2017 ANDHRA PRADESH PRAKASAM ANDHRA(VIJAYAWADA) SANIKAVARAM,PEDDARAVEEDU (AP) GODAPUVENKATA BHARANIKUMARREDDY CHATLA MITTA 9492203430 [email protected] Dec-2017 -

Societies Registered Under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the Year 2016-17

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2016-17 Vill.- Horotola, P.O.-Patkijuli, Via-Kumarikata, Dist.-Baksa 01-04-2016 BAK/260/J/01 OF 2016-17 Getsemane Prayer Centre (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781360. Vill.-Salekura, P.O.-Jania, P.S. & Dist.-Barpeta, Assam, Pin.- 01-04-2016 BAR/237/V/01 OF 2016-17 Beki Valley KrishakUnnayan Parishad, Salekura 781314. Kalahabhanga, W/No.-10, P.O. & P.S.-Barpeta Road, Dist.- 01-04-2016 BAR/237/V/02 OF 2016-17 Democratic India’s Social Association (DISA) Barpeta, Assam, Pin.-781315. Bandana Bivah Bhawan, New Amolapatty, Near Phoni Bordoloi High School, W/No.-10, Dist.-Golaghat, Assam, 01-04-2016 GOLA/239/F/01 OF 2016-17 Sanyog, Golaghat Pin.-785621 Vill. & P.O.-Kondhbori, P.S.-Mukalmua, Dist.-Nalbari, 01-04-2016 NAL/246/L/01 OF 2016-17 Hatem Development Society (N.G.O.) Assam, Pin.-781126. 01-04-2016 NAL/246/L/02 OF 2016-17 Makhibaha Gramounnayan Samity Vill. & P.O.-Makhibaha, Dist.-Nalbari, Assam, Pin.-781374. 01-04-2016 SIVA/256/F/245 North East Foundation Choladhara, P.O.- Targan, Dist.- Jorhat 1No. Itakhola, Bus Stopage, Soibari, P.O.-Itakhola, P.S.- 01-04-2016 SPR/242/H/01 OF 2016-17 Itakhola Sports Club Sootia, Dist.-Sonitpur, Assam. Jhagrarpar Nava Kallyan Development Society Vill. & P.O.-Jhagrarpar, P.S. & Dist.-Dhubri, Assam, Pin.- 02-04-2016 DBR/250/S/01 783325. H/No.-48, Ananda Nagar, Six Mile, Khanapara, Guwahati- 02-04-2016 KAM(M)/263/M/01 OF 2016-17 Suraksha Initiative 22, Dist.-Kamrup (M), Assam. -

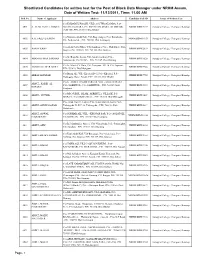

Scrutinized Database BDM

Shortlisted Candidates for written test for the Post of Block Data Manager under NRHM Assam, Date of Written Test: 11/12/2011, Time: 11.00 AM Roll No. Name of Applicant Address Candidate Full ID Venue of Written Test C/o-EMDADUL HAQUE, VILL- SOUTH SALMARA, P.O- 0001 A . H . M. FAZLUL HOQUE SOUTH SALMARA, P.S- SOUTH SALMARA, DT-DHUBRI NRHM/BDM/7147 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup (ASSAM), PIN- 783127, Dist-Dhubri C/o-Moulana Abdul Jalil, Vill- Bagersangan, P.O- Kanaibazar, 0002 A. K. FAZLUL KARIM NRHM/BDM/10739 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup P/S- Patherkandi, , PIN- 788724, Dist-Karimganj C/o-Abdus Sattar Khan, Vill-Ganakpara, P.O. - Makrikuchi, Dist- 0003 AAMIN KHAN NRHM/BDM/2879 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup Barpeta, Pin- 781305, PIN- 781305, Dist-Barpeta C/o-Sri Braja Kt. Sarma, Vill- Saruthekarabari, P.O.- 0004 ABANI KUMAR SARMAH NRHM/BDM/5528 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup Aulachowka, Pin.784125, , PIN- 784125, Dist-Darrang C/o-Lt. Manik Ch. Bora, Vill: Natugoan , PO. & P.S: Jagiroad , 0005 ABANTI KUMAR BORA NRHM/BDM/9946 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup PIN- 782410, Dist-Morigaon C/o-Darog Ali , Vill:- Kherbari Pt- I, P.O:- Kherbari, P.S:- 0006 ABBAS ALI MIAH NRHM/BDM/7753 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup Golakganj, State:- Assam, PIN- 783335, Dist-Dhubri C/o-Lt. ABDUL HAMID SARKAR, VILL.- MANASHPARA., ABDUL HABIB AL 0007 P.O.- LAKHIPUR., P.S.- LAKHIPUR, , PIN- 783129, Dist- NRHM/BDM/2278 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup ROFIQUE Goalpara C/o-MD.NURUL ISLAM., MIRIHULA VILLAGE, P.S. 0008 ABDUL MUTLIB. NRHM/BDM/2469 Saraighat College, Changsari, Kamrup MORAN , P.O. -

Ugc Academic Staff College

UGC-HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN LIST OF TEACHER PARTICIPANTS OF ACADEMIC YEAR 2016-2017 STC IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE (24-05-16 TO 30-05-16) Sl No. Name of the Teacher Participants College / University 1. Dr. Narottam Dey Visva-Bharati 2. Suchhanda Mondal Visva-Bharati Dr. Shovan Mondal Syamsundar College, The University 3. of Burdwan Dr. Mahuya Sen Birbhum Mahavidyalaya, The 4. University of Burdwan Dr. Sunita Bandopadhyay Sonamukhi College, The University 5. (Mukhopadhyay) of Burdwan Dr. Mitrajit Chatterjee Dr. Gour Mohan Roy College, The 6. University of Burdwan 7. Dr. Surjya Sarathi Bhattacharyya Asutosh College, Calcutta University Dr. Barnali Ray Basu Surendranath College, University of 8. Calcutta Dr. Nandini Bandyopadhyay Panskura Banamali College, 9. Vidyasagar University Dr. Bhola Nath Sarkar Gushkara Mahavidyalaya, The 10. University of Burdwan Dr. Biswajit Das Sreegopal Banerjee College, The 11. University of Burdwan Subrata Mukhopadhyay Krishnagar Govt. College, University 12. of Kalyani Dr. Kausik Chattopadhyay Burdwan Raj College, The 13. University of Burdwan Dr. Tuhin Ghosh Durgapur Government College, Kazi 14. Nazrul University Dr. Niloy Das Durgapur Government College, Kazi 15. Nazrul University Dr. Parnajyoti Karmakar Durgapur Government College, Kazi 16. Nazrul University Dr. Sudeshna Lahiri (Halder) Dinabandhu Mahavidyalaya, West 17. Bengal State University 18. Dr. Sudipto Mandal The University of Burdwan Dr. Alokkumar Ghorai Kalimpong College, North Bengal 19. University Dr. Bibaswan Mondal Dum Dum Motijheel College, West 20. Bengal State University 21. Mr. Arup Kumar Deka Darrang College, Gauhati University 22. Dr. Pankaj Hazarika Darrang College, Gauhati University Dr. Minakshi Chakraborty (Sen) Asansol Girls' College, Kazi Nazrul 23.