Copyright by Jesse Noah Klein 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesus, the Righteous Branch of Jesse — Matthew 3:1-12 Page 1 Advent 2A Pastor Douglas Punke in the Name of C Jesus. in This Ad

Jesus, the Righteous Branch of Jesse — Matthew 3:1-12 Page 1 Advent 2a Pastor Douglas Punke In the name of c Jesus. In this Advent season, a watchword is the word “prepare.” Matthew tells us this is why John the Baptist is significant. John makes his appearance in the Judean wilderness as the voice foretold by Isaiah: the “voice of one crying in the wilderness,” preparing “the way of the Lord.” In our busy lives outside of church, in this Advent season, I’m sure there is a lot of preparing taking place. The gifts under the Christmas tree don’t just miraculously appear; being a bit circumspect here…there is no “jolly old elf” delivering them from the North Pole. The house doesn’t get decorated on its own. Christmas goodies don’t make themselves. And magic won’t make your festive Christmas dinner. All these require preparation. You may be hosting a Christmas gathering at your home; you may be going to have holiday guests to your home. These require preparation, perhaps even a good old-fashioned house cleaning. John came on the scene knowing that he was the one sent to prepare for the coming of the Messiah. His father Zechariah sang of it at John’s birth, and no doubt told John many times: “you, child, will be called the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give knowledge of salvation to his people in the forgiveness of their sins …” (Luke 1:76-77). That is, John came on the scene to give Israel a figurative house cleaning. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Jesse Tree Bible-Story Guide

Jesse Tree Bible-Story Guide Person Scripture Symbol Adam and Eve Genesis 3:1-24 an apple Noah Genesis 6:11—9:17 (or 8:21—9:17) ark or rainbow (or Genesis 6:5-9, 7:7-16, 8:13-17, 9:12-16) Abraham and Sarah Genesis 12:1-7, 15:1-6 camel, tent or star Isaac Genesis 22:1-19 ram Rebecca Genesis 25:19-34; and 27 a well Jacob Genesis 28:10-22 or 32: 25-31 a ladder Rachel and Leah Genesis 29:15-30 a veil Joseph Genesis 37:3-4 and 17-36; 50:15-21 coat of many colors (or Genesis 37:1—45:28) Moses Exodus 3:1-15 bush Exodus 20:1-21 Ten Commandments (tablets) Rahab Joshua 2:1-21 rope Joshua Joshua 6:1-20 trumpet Deborah Judges 4:1-16 palm tree or tent peg & mallet Gideon Judges 7:1-8, 15-20 torch Samson Judges 13:1-5; 15:14-17 jawbone Ruth Ruth chapters 1—4 anchor (for faithfulness) or grains of wheat Hannah 1 Samuel 1:1-20, 24-28; 2:18-20 small robe Samuel 1 Samuel 3:1-19; 16:1-13 oil David 1 Samuel 16:1-16 stringed instrument or slingshot or crown (for king) Solomon 1 Kings 3:4-15 crown or scepter Elijah 1 Kings 19:3-13; 2 Kings 2:1-5, 9-13 chariot Jonah Jonah 1:1-17; 2:10; 3:1-3 whale Isaiah Isaiah 9:1-6 and 11:1-9 branch or lion and lamb Ezekiel Ezekiel 37:1-14 and 24-28 bones Esther Esther 2:17-18; 3:8-15; 4:7-16; 7:10 crown Daniel Daniel 1:1-4; 6:1-28; 7:13-14 lion Malachi Malachi 4:1-6 sun Elizabeth Luke 1:5-25 a home, angel, temple or altar John the Baptist Luke 1:57-80 shell and water or a reed Joseph Matthew 1:18-25 hammer or saw Mary Luke 1:26-38, 39-56 lily Luke 2:1-14 manger Background Information Many of us have photographs of parents, grandparents, great-aunts and uncles, and great- grandparents. -

The Jesse Tree Who Was Jesse?

THE JESSE TREE WHO WAS JESSE? The prophet Isaiah foretold the coming of the Messiah. Isaiah's words helped people L- know that the One who was promised to them by God would be born into the family of Jesse. " A shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse and from his roots a bud shall blossom." Isaiah II: I-10 Jesse of Bethlehem had seven sons. Jesse's youngest son, David, watched over the sheep for him. One day the prophet Samuel came to Jesse's house and met David. Samuel anointed David. Many years later, David became King. It was from Jesse that the family tree branched out to David and his descendants. Jesse and David were ancestors of Jesus. At the time of Jesus' birth all those who belonged to the family of David had to return to the town of Bethlehem because a census was being taken. Since Joseph and Mary were of the House of David, they had to travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem to register. WHAT IS THE JESSE TREE? The Jesse Tree is a special tree used during the season of Advent. The Jesse Tree represents the family tree of Jesus. It serves as a reminder of the human family of Jesus. The uniqueness of the Jesse Tree comes from the ornaments that are used to decorate it. They are symbols that depict the ancestors of Jesus or a prophecy fulfilled at His coming. Traditionally, the Jesse Tree ornaments also included representations of Adam, F.ve and Creation. These symbolize the promise.. The Jesse Tree Book SUGGESTIONS FOR JESSE TREE ORNAMENTS Directions: The list of names below are Sarah: Genesis 15 and 21 suggestions that can be used for Jesse Tree Ornaments. -

The Jesse Tree

The Jesse Tree Then a shoot will spring from the stem of Jesse and a branch from his root will bear fruit. And the Spirit of the Lord will rest upon Him. Isaiah 11:12 Barbara J. Kleeman What is a Jesse Tree? The Jesse tree is a symbolic tree that is decorated each week, usually by the children, with ornaments or objects that represent Old Testament events from Creation to the Birth of Jesus. The ornaments are traditionally handmade, and are added one each day of Advent, or a group on each Sunday, with explanations of the symbols and a brief verse of Scripture from the story represented. The Jesse Tree is named from Isaiah 11:1: "A shoot will spring forth from the stump of Jesse, and a branch out of his roots." It is a vehicle to tell the Story of God in the Old Testament, and to connect the Advent Season with the faithfulness of God across 4,000 years of history. The branch is a biblical sign of newness out of discouragement, which became a way to talk about the expected Messiah (e.g., Jer 23:5). It is therefore an appropriate symbol of Jesus the Christ, who is the revelation of the grace and faithfulness of God. The devotionals that join the construction of the Jesse Tree are designed to be used each day during the month of December, except for the Sundays of Advent. The lessons are in chronological order from God the Father to Adam and his sons continuing through to the birth of the Son of God. -

A COMPARATIVE STUDY of the NATION of ISLAM and ISLAM Dwi

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE NATION OF ISLAM AND ISLAM Dwi Hesti Yuliani-Sato A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2007 Committee: Dr. Lillian Ashcraft-Eason, Advisor Dr. Awad Ibrahim ©2007 Dwi Hesti Yuliani-Sato All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Lillian Ashcraft-Eason, Advisor This study compares the Nation of Islam with the religion of Islam to understand the extent of its religious kinship to Islam. As with other religions, there are various understandings of Islam and no single agreement on what constitutes being a Muslim. With regard to that matter, the Nation of Islam’s (NOI) teachings and beliefs are regarded as unconventional if viewed from the conventions of Islam. Being unconventional in terms of doctrines and having a focus on racial struggle rather than on religious nurturing position the Nation of Islam more as a social movement than as a religious organization. Further, this raises a question, to some parties, of whether the NOI’s members are Muslims in the sense of mainstream Islam’s standard. It is the issue of conventional versus unconventional that is at the core of this study. The methodologies used are observation, interview, and literary research. Prior to writing the thesis, research on the Nation of Islam in Toledo was conducted. The researcher observed the Nation of Islam in Toledo and Savannah, Georgia, and interviewed some people from the Nation of Islam in Toledo and Detroit as well as a historian of religion from Bowling Green State University. -

Jesse Tree Symbols Persons Events/Themes Scripture Symbols 1 Sam 16:1-13 Introduction of the Jesse Tree Isa 11:1-10 the Tree

Jesse Tree Symbols Persons Events/Themes Scripture Symbols 1 Sam 16:1-13 Introduction of the Jesse Tree Isa 11:1-10 The Tree God Creation Gen 1:1-2:3 Dove Tree with Fruit or Adam and Eve The First Sin Gen 2:4-3:24 Apple Noah The Flood Gen 6:11-22, 7:17-8:12, 20-9:17 Rainbow or Ark Abraham The Promise Gen 12:1-7, 15:1-6 Field of Stars Isaac Offering of Isaac Gen 22:1-19 Ram Jacob Assurance of the Promise Gen 27:41-28:22 Ladder Joseph God's Providence Gen 37, 39:1-50:21 Sack of Grain or Coat Moses God's Leadership Exod 2:1-4:20 Burning Bush Israelites Passover and Exodus Exod 12:1-14:31 Lamb God Giving the Torah at Sinai Exod 19:1-20:20 Tablets of the Torah Joshua The Fall of Jericho Josh 1:1-11, 6:1-20 Ram's Horn Trumpet Gideon Unlikely Heroes Judg 2:6-23, 6:1-6, 11-8:28 Clay Water Pitcher Samuel The Beginning of the Kingdom 1 Sam 3:1-21, 7:1-8:22, 9:15-10:9 Crown 1 Sam 16:1-23-17:58, Shepherd's Crook or David A Shepherd for the People 2 Sam 5:1-5, 7:1-17 Harp Elijah The Threat of False Gods 1 Kng 17:1-16, 18:17-46 Stone Altar Hezekiah Faithfulness and Deliverance 2 Kng 18:1-19:19, 32-37 An Empty Tent Fire Tongs with Hot Isaiah The Call to Holiness Isa 1:10-20, 6:1-13, 8:11-9:7 Coal Jer 1:4-10, 2:4-13, 7:1-15, 8:22- Jeremiah The Exile 9:1-11 Tears Habakkuk Waiting Hab 1:1-2:1, 3:16-19 Stone Watchtower Nehemiah Return and Rebuilding Neh 1:1-2:8, 6:15-16, 13:10-22 City Wall John the Baptist Repentance Luke 1:57-80, 3:1-207:18-30 Scallop Shell Mary The Hope for a Future Luke 1:26-38 White Lily Elizabeth Joy Luke 1:39-56 Mother and Child Zechariah Anticipation Luke 1:57-80 Pencil and Tablet Carpenter's Square Joseph Trust Matt 1:19-25 or Hammer Magi Worship Matt 2:1-12 Star or Candle Jesus Birth of the Messiah Luke 2:1-20 Manger Christ The Son of God John 1:1-18 Chi-Rho Symbol. -

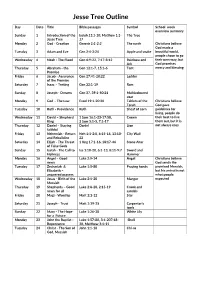

Jesse Tree Outline and Timetable

Jesse Tree Outline Day Date Title Bible passages Symbol School week overview summary Sunday 1 Introduction of the Isaiah 11:1-10; Matthew 1:1- The Tree Jesse Tree 17 Monday 2 God - Creation Genesis 1:1-2:3 The earth Christians believe God made a Tuesday 3 Adam and Eve Gen 2:4-3:24 Apple and snake beautiful world, people chose to go Wednesday 4 Noah - The Flood Gen 6:9-22, 7:17-8:12 Rainbow and their own way, but Ark God promises Thursday 5 Abraham - the Gen 12:1-7, 15:1-6 Tent mercy and blessing Promise Friday 6 Jacob - Assurance Gen 27:41-28:22 Ladder of the Promise Saturday 7 Isaac – Testing Gen 22:1-19 Ram Sunday 8 Joseph - Dreams Gen 37, 39:1-50:21 Multicoloured coat Monday 9 God – The Law Exod 19:1-20:20 Tablets of the Christians believe Torah God gave Tuesday 10 Ruth - Providence Ruth Sheaf of corn guidelines for living, people do Wednesday 11 David – Shepherd 1 Sam 16:1-23-17:58, Crown their best to live King 2 Sam 5:1-5, 7:1-17 them out, but it is Thursday 12 Daniel – Staying Daniel Lion not always easy faithful Friday 13 Nehemiah - Return Neh 1:1-2:8, 6:15-16, 13:10- City Wall and Rebuilding 22 Saturday 14 Elijah - The Threat 1 Kng 17:1-16, 18:17-46 Stone Altar of False Gods Sunday 15 Isaiah - The Call to Isa 1:10-20, 6:1-13, 8:11-9:7 Sword and Holiness Hammer Monday 16 Angel – Good Luke 2:9-14 Angel Christians believe news God sends the Tuesday 17 Zechariah & Luke 1:5-80 Praying hands promised Messiah, Elizabeth – but his arrival is not answered prayers what people Wednesday 18 Jesus - Birth of the Luke 2:1-20 Manger expected Messiah Thursday 19 Shepherds – Good Luke 2:8-20, 2:15-19 Crook and news for all sandals Friday 20 Magi - Worship Matt 2:1-12 Star Saturday 21 Joseph - Trust Matt 1:19-25 Carpenter's tools Sunday 22 Mary - The Hope Luke 1:26-38 White Lily for a Future Monday 23 John the Baptist - Luke 1:57-80, 3:1-207:18- Shell Repentance 30, Matthew 3:1-11 Tuesday 24 Christ - The Son of John 1:1-18 Chi-ro God, Messiah . -

The Songs of Jesse Adams Ebook, Epub

THE SONGS OF JESSE ADAMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter McKinnon | 352 pages | 24 Jul 2014 | ACORN PRESS | 9780987428677 | English | Victoria, Australia The Songs of Jesse Adams PDF Book This was what touched me when watching The Songs of Jesse Adams. You may also like. Jesse Adams supported all the right causes — but over and above that he presented himself. This is what I believe Jesus ultimately does for each of us. You're now in slide show mode. But not all will celebrate the rising tide of influence of this charismatic figure whose words and actions challenge those in power - the media, the politicians, the church. Look for similar items by category. Jesse organises, not for water to become wine, but beer to become champagne. He responded quickly and was a pleasure to work with! Despite the nostalgic setting, the story does not seem dated or irrelevant. A natural talent with extreme professionalism this guy is amazing to work with! The Circus Left Town. He went above and beyond in providing us with high-quality recordings, and was extremely gracious and patient throughout the production process. My gut feeling is that this novel stands up on its own merits as an engaging story, but I will be interested to see how my reading group of Canberra based women, most of whom do not have a strong church background, receive the novel when it comes up in our program for About Fishpond. Francine Rivers. Christian faith has managed to domesticate Jesus in so many ways that the New Testament narratives of Jesus have often ceased to be of much interest to Christians themselves, let alone to non-Christians. -

The Jesse Tree: Advent Devotional Quick-Start Guide for Catholic Families a Resource from Catholic Sprouts

The Jesse Tree: Advent Devotional Quick-Start Guide for Catholic Families A Resource from Catholic Sprouts The Jesse Tree is simply an exploration of Jesus’s Ancestors. Use the guide below to bring this practice to your own home. Since the longest Advent can be is 29 days, below you will find 29 characters from the Bible. For each character you will find a symbol and a Bible verse. Traditionally the faithful read the Bible verse together around the Advent wreath and then hang an ornament with the corresponding symbol on a tree. Since most Advent seasons are less than 29 days, you will need to omit a few characters most years. Finally, the verses listed below are just suggestions. There are other verses that could be read for each character. For more Jesse Tree ideas, head here: www.dosmallthingswithlove.com/jesse-tree Day Character Symbol Bible Verses 1 Jesse Tree Stump Isaiah 1 2 Creation of the World Globe Genesis 1--2:3 3 First Sin Apple Genesis 2:4--3:24 4 Cain and Abel Sickle Genesis 4:1-16 5 Noah Arc Genesis 6:5-22, 7:17--8:12--9:17 6 Abraham Stars Genesis 12:1-7, 15:1-6 7 Isaac Ram Genesis 22:1-19 8 Jacob Ladder to Heaven Genesis 27:41--28:22 9 Joseph Multi-colored coat Genesis 37:3-36, 50:15-21 10 Burning Bush Burning Bush Exodus 2--4:20 11 The Passover Lamb Exodus 12--14 12 The 10 Commandments Tablets Exodus 19--20 13 Joshua Horn Joshua 1:1-11, 6:1-20 14 Gideon Jug Judges 2:6-23, 6--8:28 15 Ruth Wheat Ruth 1--2, 4:13-22 16 David Slingshot 1 Samuel 17: 32-51 17 Elijah Stone Altar and Fire 1 Kings 17:1-16, 18:17-46 18 Isaiah Hot Coal and Tongs Isaiah 1:10-20, 6:1-13, 8:11--9:7 19 Jeremiah Tears Jeremiah 1:4-10, 2:4-13, 7:1-15 20 Habakkuk Watch Tower Habakkuk 1:12--2:1, 3:16-19 21 Daniel Lion Daniel 6:1-28 22 Ester Crown Ester 2, 3:8-11, 5:1-8, 7 23 Jonah Whale The Book of Jonah 24 Nehemiah City Wall Nehemiah 1--2:8, 6:15-16, 13:10-22 25 Zechariah Paper and Pen Luke 1:8-38 26 Mary Lily Luke 1:26-56 27 Joseph Tools Luke 1:18-25 28 Baby Jesus Baby in Manger Luke 2:1-20 29 Jesus the Lord Bible John 1 . -

WARRANT LIST UPDATED WEEKLY Page 1 of 38 Warrants on This List Are Current As of the Date Listed Above

01/15/2021 CITY OF MANKATO WARRANT LIST UPDATED WEEKLY Page 1 of 38 Warrants on this list are current as of the date listed above. Warrants are served on a regular basis and a warrant on this list may already have been served. If you know the whereabouts of someone on this list, please call (507)387-8780. Do not attempt to arrest someone yourself. Abarca Bonilla, David Wilfrdo Age: 40 SEX: M RACE: W Minneapolis, MN 55417 Charge: FTA/ Speeding/ Driving Without A Valid License/ No Proof Of Insurance Abdi, Mohamed Aden Age: 25 SEX: M RACE: B Mankato, MN 56001 Charge: 5012/OVS SIMPLE ROBBERY / TERRORISTIC THREATS Abdi, Mohamed Yusef Age: 31 SEX: M RACE: U Mankato, MN 56001 Charge: FTA/NO MN DRIVERS LICENSE Abdo, Frank Lee Age: 61 SEX: M RACE: W Mankato, MN 56001 Charge: 5012/OVS POSSESS AMMO/ANY FIREARM-CONVICTION OR ADJUDCIATED DELINQUENT FOR CRIME OF VIOLENCE Abdo, Frank Lee Age: 61 SEX: M RACE: W Mankato, MN 56001 Charge: 5012/OVS THREATS OF VIOLENCE Abdulle, Mohamed Ali Age: 19 SEX: M RACE: B Hopkins, MN 55343 Charge: 5015/FTA 5TH DEGREE ASSAULT Abner, Jason William Age: 35 SEX: M RACE: W Granite Falls, MN 562411132 Charge: FTA/5TH DEGREE POSSESSION CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE Ademole Sadipe, Crystal Marie Age: 36 SEX: F RACE: W Mankato, MN 56001 Charge: FTA/ Theft Aden, Ahmed Sharif Age: 42 SEX: M RACE: B Minneapolis, MN Charge: 5015/FTA TAMPERING WITH A WITNESS / STALKING / THREATS OF VIOLENCE Aden, Ahmed Sharif Age: 42 SEX: M RACE: B Minneapolis, MN Charge: 5015/FTA 2ND DEGREE ASSAULT / DOMESTIC ASSAULT Ahmed, Ahmed Mohamed Age: 27 SEX: M -

Ruth and Naomi

A Good Shepherd Sacred Story Ruth and Naomi Adapted by: Brenda J. Stobbe Illustrations by: Jennifer Schoeneberg 2nd Edition ©Good Shepherd, Inc. 1991, 1992 Good Shepherd, a registered trademark of Good Shepherd, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. RUTH AND NAOMI .... MATERIALS - small wicker basket to hold: - wooden figure of Naomi - wooden figure of Orpah - wooden figure of Ruth - wooden figure of Boaz 1 Orpah Naomi Boaz Ruth 2 RUTH AND NAOMI ...• RUTH 1, 2, 3, 4 ACTIONS WORDS After speaking, stand and get the story from Watch carefully where I go to get this story 'it's shelf. Return to the circle and sit down, so you will know where to find it if you placing the basket next to you. choose to make this story your work today or another day. As you sit in silence, stroke one of the All the words to this story are inside of me. wooden figures to center yourself and the Will you please make silence with me so I children. can find all the words to share this story of God's people with you? Place the Naomi figure in the center. Once there was a woman named Naomi, who was one of the Jewish people of God. Move the Naomi figure six inches to the She and her husband and her two sons had right. gone to the gentile country of Moab when there was a famine in Judah. Place Ruth and Orpah next to Naomi on the right. There her husband died. Then her two sons married gentile women.