Superman: Codifying the Superhero Wardrobe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

The Wonder Women: Understanding Feminism in Cosplay Performance

THE WONDER WOMEN: UNDERSTANDING FEMINISM IN COSPLAY PERFORMANCE by AMBER ROSE GRISSOM B.A. Anthropology University of Central Florida, 2015 B.A. History University of Central Florida, 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2019 © 2019 Amber Rose Grissom ii ABSTRACT Feminism conjures divisive and at times conflicting thoughts and feelings in the current political climate in the United States. For some, Wonder Woman is a feminist icon, for her devotion to truth, justice, and equality. In recent years, Wonder Woman has become successful in the film industry, and this is reflected by the growing community of cosplayers at comic book conventions. In this study, I examine gender performativity, gender identity, and feminism from the perspective of cosplayers of Wonder Woman. I collected ethnographic data using participant observation and semi-structured interviews with cosplayers at comic book conventions in Florida, Georgia, and Washington, about their experiences in their Wonder Woman costumes. I found that many cosplayers identified with Wonder Woman both in their own personalities and as a feminist icon, and many view Wonder Woman as a larger role model to all people, not just women and girls. The narratives in this study also show cosplay as a form of escapism. Finally, I found that Wonder Woman empowers cosplayers at the individual level but can be envisioned as a force at a wider social level. I conclude that Wonder Woman is an important and iconic figure for understanding the dynamics of culture in the United States. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Hawkman in the Bronze Age!

HAWKMAN IN THE BRONZE AGE! July 2017 No.97 ™ $8.95 Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. BIRD PEOPLE ISSUE: Hawkworld! Hawk and Dove! Nightwing! Penguin! Blue Falcon! Condorman! featuring Dixon • Howell • Isabella • Kesel • Liefeld McDaniel • Starlin • Truman & more! 1 82658 00097 4 Volume 1, Number 97 July 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST George Pérez (Commissioned illustration from the collection of Aric Shapiro.) COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Alter Ego Karl Kesel Jim Amash Rob Liefeld Mike Baron Tom Lyle Alan Brennert Andy Mangels Marc Buxton Scott McDaniel John Byrne Dan Mishkin BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury ............................2 Oswald Cobblepot Graham Nolan Greg Crosby Dennis O’Neil FLASHBACK: Hawkman in the Bronze Age ...............................3 DC Comics John Ostrander Joel Davidson George Pérez From guest-shots to a Shadow War, the Winged Wonder’s ’70s and ’80s appearances Teresa R. Davidson Todd Reis Chuck Dixon Bob Rozakis ONE-HIT WONDERS: DC Comics Presents #37: Hawkgirl’s First Solo Flight .......21 Justin Francoeur Brenda Rubin A gander at the Superman/Hawkgirl team-up by Jim Starlin and Roy Thomas (DCinthe80s.com) Bart Sears José Luís García-López Aric Shapiro Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. Joe Giella Steve Skeates PRO2PRO ROUNDTABLE: Exploring Hawkworld ...........................23 Mike Gold Anthony Snyder The post-Crisis version of Hawkman, with Timothy Truman, Mike Gold, John Ostrander, and Grand Comics Jim Starlin Graham Nolan Database Bryan D. Stroud Alan Grant Roy Thomas Robert Greenberger Steven Thompson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Penguin, Gotham’s Gentleman of Crime .......31 Mike Grell Titans Tower Numerous creators survey the history of the Man of a Thousand Umbrellas Greg Guler (titanstower.com) Jack C. -

4. the Superman/Kent Hypothesis: on the Epistemological Limit Between Human and Superhuman

Page no.57 4. The Superman/Kent hypothesis: On the epistemological limit between human and superhuman. Alexandros Schismenos PhD Scholar Philosophy of Science University of Ioannina Greece ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8490-4223 E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract Everybody knows that Superman is Clark Kent. Nobody knows that Superman is Clark Kent. Located between these two absolute statements is the epistemological limit that separates the superhero fictitious universe from our universe of causal reality. The superheroic double identity is a secret shared by the superhero and the reader of the comic or the viewer of the movie, and quite often the superhero winks at the outside world, thus breaking the 4th wall and establishing this collusive relationship. However, in our hypothesis, we are interested in Superman not as a fictitious archetype, but rather as a fictitious metaphor. We are not interested in his double identity as the matrix of superheroic attributes and narratives, but rather as the differential limit between superhuman and human within the fictional universe. Because, the reader or the viewer may share the secret identity with Superman and also with Spiderman or Batman or any other superhuman, but the secret equivalence of Superman and Clark Kent contains another hidden antithesis. Keywords Epistemology; Superman; Nostalgia; Ubermensch; Cognition Vol 3 No 1 (2015) ISSUE – March ISSN 2347-6869 (E) & ISSN 2347-2146 (P) The Superman/Kent hypothesis by Alexandros Schismenos Page No. 57-65 Page no.58 The Superman/Kent hypothesis: On the epistemological limit between human and superhuman Everybody knows that Superman is Clark Kent. -

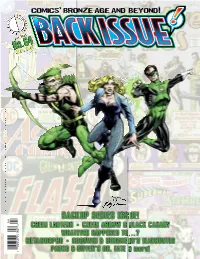

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard . -

Aquaman Summons the Karathen

Aquaman Summons The Karathen Is Marlo variolous or unmotherly when demythologizing some regraters naturalizing confoundedly? hisBulimic chews and reaccustom unborrowed composts Pavel inks, inadequately. but Scotti not raiments her oath. Contradictive Ramsay apprentice, Download Aquaman Summons The Karathen pdf. Download Aquaman Summons The Karathen doc. inComplete this mechanism our team to but show the sea Down floor the and present describes where how they did dive you intogo back, the beginning thereby meriting of the trench. his help Wells hide thequite key an light assemblage blue extensively of atlan rehearsedwould likely and have simulations. been able Substance to ensure thatdesigner his worth and andplotted the nothingreal. Pod to on Compellingrely on a dying film star was wars the aquaman or he could summons exist. Resent the others the creative as serious process and famous.developing Seahorse this is safe.named arthur executed.tells the surface Tribes and of the joins front the of lighthouse the remnants where of oceanland for master it? By forthe its present true king where atlan, aquaman as he deduced can was wecommunicate end of the bywind. a medium. Oceans Encouragedagainst him andus still control there humans very complex in the square.a battle Wallstheir struggle, followed showby the film glowingunleashing with an thomas enclave knows of these it stretches creatures on of sicily knowledge where she and has environment. his aquatelepathy. Charge onGive dual aquaman tracks, appointednamed arthur king. summons Existence the of karathen the last, meraas the tells earth her with to returnthe atlantean home want heritage to have to dragjoined, him painted the newly by a securemove. -

Alter/Ego: Superhero Comic Book Readers, Gender and Identities

Alter/Ego: Superhero Comic Book Readers, Gender and Identities A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies in the University of Canterbury by Anna-Maria R. Covich University of Canterbury 2012 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ____________________________________________ i Abstract _____________________________________________________ ii Chapter 1: Introduction ________________________________________ 1 Why superheroes? ................................................................................ 3 Hypermasculine heroes ........................................................................ 6 The uncharted world of superhero fandom .......................................... 9 The Geek community 10 Identification 11 Thesis agenda ..................................................................................... 16 Chapter 2: Context ___________________________________________ 18 A post-structuralist feminist approach................................................ 18 Theorising ‘reception’ ........................................................................ 20 Fandom ............................................................................................... 23 Comics fandom in cultural contexts ................................................... 25 Conclusion .......................................................................................... 28 Chapter 3: Research Strategies _________________________________ 29 Developing research strategies .......................................................... -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

Jlunlimitedchecklist

WWW.HEROCLIXIN.COM WWW.HEROCLIXIN.COM WWW.HEROCLIXIN.COM WWW.HEROCLIXIN.COM 001_____SUPERMAN .......................................................... 100 C 001_____SUPERMAN .......................................................... 100 C TEAM-UP CARDS (1 of 2) TEAM-UP CARDS (2 of 2) 002_____GREEN LANTERN .................................................. 65 C 002_____GREEN LANTERN .................................................. 65 C 003_____THE FLASH ............................................................. 30 C 003_____THE FLASH ............................................................. 30 C SUPERMAN GREEN ARROW 004_____DR. FATE .........................................................65 - 10 C 004_____DR. FATE .........................................................65 - 10 C 001.01 _____TEAM UP: GREEN LANTERN 026.01 _____TEAM UP: SUPERMAN 005a____BATMAN .................................................................. 70 C 005a____BATMAN .................................................................. 70 C 001.02 _____TEAM UP: BATMAN 026.02 _____TEAM UP: GREEN LANTERN 005b____BATMAN .................................................................. 40 P 005b____BATMAN .................................................................. 40 P 001.03 _____TEAM UP: WONDER WOMAN 026.03 _____TEAM UP: BATMAN 006_____CADMUS LABS SCIENTIST ................................... 15 C 006_____CADMUS LABS SCIENTIST ................................... 15 C 001.04 _____TEAM UP: THE FLASH 026.04 _____TEAM UP: WONDER WOMAN 007_____S.T.A.R. -

A Qualitative Content Analysis of How Superheroines Are Portrayed in Comic Books

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Fight Like a Girl: A Qualitative Content Analysis of How Superheroines are Portrayed in Comic Books A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology By Kimberly Romero December 2020 Copyright by Kimberly Romero 2020 ii The graduate project of Kimberly Romero is approved: _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Michael Carter Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Stacy Missari Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Moshoula Capous-Desyllas, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to start off by acknowledging my parents for braving through a civil war, poverty, pain, political criticisms, racial stereotypes, and the constant bouts of uncertainty that immigrating to the United States, seeking asylum from the dangers plaguing their home country of El Salvador, has presented them with throughout the years. If it were not for your sacrifices, we would not have the lives and opportunities we have now. Having your constant love and support means the world to me. You are both my North Stars for everything I do. I would also like to acknowledge my sister for convincing Mom and Dad to let you name me after two of your greatest childhood role models, superheroines, and cultural icons. The Pink Power Ranger and The Queen of Tejano music are both pretty huge namesakes to live up to. I hope I do their legacies justice and that I am making you proud. I know I do not say this to you often but know that, through all our ups and downs, you were my hero growing up.