The Provincial Archive As a Place of Memory: the Role of Former Slaves in the Cuban War of Independence (1895-98)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

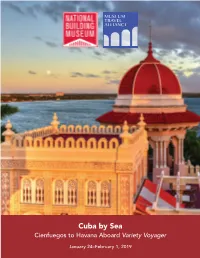

Cuba by Sea Cienfuegos to Havana Aboard Variety Voyager

MUSEUM TRAVEL ALLIANCE Cuba by Sea Cienfuegos to Havana Aboard Variety Voyager January 24–February 1, 2019 MUSEUM TRAVEL ALLIANCE Dear Members and Friends of the National Building Museum, Please join us next January for a cultural cruise along Cuba’s Caribbean coast. From Cienfuegos to Havana, we will journey aboard a privately chartered yacht, discovering well-preserved colonial architecture and fascinating small museums, visiting talented artists in their studios, and enjoying private concerts and other exclusive events. The Museum Travel Alliance (MTA) provides museums with the opportunity to offer their members and patrons high-end educational travel programming. Trips are available exclusively through MTA members and co-sponsoring non- profit institutions. This voyage is co-sponsored by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Association of Yale Alumni. Traveling with us on this cultural cruise are a Cuban-American architect and a partner in an award-winning design firm, a curator from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a Professor in the Music Department and African American Studies and American Studies at Yale University. In Cienfuegos, view the city’s French-accented buildings on an architectural tour before boarding the sleek Variety Voyager to travel to picturesque Trinidad. Admire the exquisite antiques and furniture displayed in the Romantic Museum and tour the studios of prominent local artists. Continue to Cayo Largo to meet local naturalists, and to remote Isla de la Juventud to see the Panopticon prison (now a museum) that once held Fidel Castro. We will also visit with marine ecologists on María la Gorda, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, before continuing to Havana for our two-day finale. -

Assistente De

HEAT & SYMPATHY 10 Days Havana - Guama - Cienfuegos - Sancti Spiritus - Camaguey - Guardalavaca Day 1: HAVANA Arrival at the José Martí International Airport. Transfer to the hotel selected. Accommodation and dinner. Day 2: HAVANA Breakfast at the hotel. Departure to make the City Tour of Havana, with a walk through Old Havana, a World Heritage Site, and the 4 squares of the old town: San Francisco de Asís Square, Old Square, Armas Square with visit to the Museum of the Captains General, Cathedral Square. Visit to the Ron Bocoy Factory and the Handicraft Fair, in the renovated Plaza de San José. Lunch at a local restaurant. At the end, bus tour at modern Havana, stop for photos in the National Capitol and in the Plaza de la Revolución. Return to the hotel. Night available for the enjoyment of optional activities. Day 3: HAVANA – GUAMÁ - CIENFUEGOS Breakfast at the hotel. Departure to Guamá, where you can see the artistic reproduction of a Taino village located in the Zapata Peninsula, Matanzas province. Boat trip through the Laguna del Tesoro admiring the ora and fauna of the place. Upon return, visit the Crocodile Hatchery. Lunch in a restaurant of the zone. At the end, departure to Cienfuegos, known as the Pearl of the South and declared a World Heritage Site. Walk on foot from the Paseo del Prado, along the Boulevard to the José Martí Park. Visit to the Tomás Terry Theater and the Palacio de Valle. Accommodation and dinner at the Hotel. Day 4: CIENFUEGOS – TRINIDAD – SANCTI SPÍRITUS Breakfast at the hotel. Departure to the city of Trinidad, known as the Jewel of Cuba. -

State of Ambiguity: Civic Life and Culture in Cuba's First Republic

STATE OF AMBIGUITY STATE OF AMBIGUITY CiviC Life and CuLture in Cuba’s first repubLiC STEVEN PALMER, JOSÉ ANTONIO PIQUERAS, and AMPARO SÁNCHEZ COBOS, editors Duke university press 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data State of ambiguity : civic life and culture in Cuba’s first republic / Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos, editors. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5630-1 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5638-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba—History—20th century. 3. Cuba—Politics and government—19th century. 4. Cuba—Politics and government—20th century. 5. Cuba— Civilization—19th century. 6. Cuba—Civilization—20th century. i. Palmer, Steven Paul. ii. Piqueras Arenas, José A. (José Antonio). iii. Sánchez Cobos, Amparo. f1784.s73 2014 972.91′05—dc23 2013048700 CONTENTS Introduction: Revisiting Cuba’s First Republic | 1 Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos 1. A Sunken Ship, a Bronze Eagle, and the Politics of Memory: The “Social Life” of the USS Maine in Cuba (1898–1961) | 22 Marial Iglesias Utset 2. Shifting Sands of Cuban Science, 1875–1933 | 54 Steven Palmer 3. Race, Labor, and Citizenship in Cuba: A View from the Sugar District of Cienfuegos, 1886–1909 | 82 Rebecca J. Scott 4. Slaughterhouses and Milk Consumption in the “Sick Republic”: Socio- Environmental Change and Sanitary Technology in Havana, 1890–1925 | 121 Reinaldo Funes Monzote 5. -

Yachtcharter - Cuba

VPM Yachtcharter - Cuba Yacht - charter Cuba Cuba is built on myths and metaphors. In the 50’s Cuba was the Monte Carlo of the Caribbean where stars like Errol Flynn or authors like Hemmingway sipped their rum cocktail. Then in the 60’s came the radical revolution and it was followed by the regime of Castro during the last three decades. These are only little episodes in the long history of the Cuban people. Columbus was the first european to discover the island in 1492 and he described it in the following way: "The exceptional beauty beats everything with its magic and grace just as the day surpasses the night with its brilliance." There are thus good reasons for Cuba’s reputation as the pearl of the Antilles. Cuba is located at the entry of the Gulf of Mexico and just below the Northern Tropic. To the west of Cuba lies the Yucatan Peninsula, to the east there is Haiti, to the south there lies Jamaica and to the north at a distance of around 80 nautical miles you will find Florida. 4195 smaller islands and sandbanks are part of the archipelago. Every sailor can trust the north-eastern trade winds. 10 to 25 knots are the norm. There is besides that something noteworthy about Cuba. It has the lowest rate of hurricane appearances in the Antilles. The waters around Cuba Due to the geographical size of Cuba you have to decide in which waters you want to sail. At your disposal are Varadero, which is appealing with its good international flight connections, comfortable hotels and what are probably the island’s most beautiful beaches or Cayo Largo, the Caribbean alternative on the fresher Atlantic coast or even La Habana where you can find one of the world’s most beautiful diving paradises. -

History News Network Journey to Havana, Cienfuegos, and Trinidad, Cuba December 13-20, 2017

HISTORY NEWS NETWORK JOURNEY TO HAVANA, CIENFUEGOS, AND TRINIDAD, CUBA DECEMBER 13-20, 2017 Wednesday, Dec 13 Midday Arrival into Havana 4 pm Check-in at the four-star NH Capri Hotel de Habana, an historic, art-deco hotel located in the thriving Vedado district of Havana 5:30 pm Afternoon discussion with a local historian about early Cuban History, the Conquest and Colonization of Cuba by the Spanish Empire in the early 16th century, and specifically of San Cristobal de La Habana village. 7:30 pm Welcome dinner at Paladar San Cristobal. Located in the heart of Central Havana, this paladar has a reputation of excellence in both atmosphere and local cuisine. The staff is particu- larly proud of their photos with President Obama, who ate here during his historic visit last year. Thursday, Dec 14 9 am Guided walking tour of the Old City led by a specialist from the City Historian’s office. Wander through the Plaza de Armas, a scenic tree-lined plaza formerly at the center of influence in Cuba. It is surrounded by many of the most historic structures in Havana as well as important monuments. See the Plaza de San Francisco, a cobbled plaza surrounded by buildings dating from the 18th century, dominated by the baroque Iglesia and Convento de San Francisco dating from 1719. Visit the Plaza Vieja, surrounded by sumptuous houses of the Ha- vana aristocracy from the 18th and 19th centuries. Visit Plaza de la Catedral and the Catedral de San Cristóbal de La Habana. 12 pm Lunch at Doña Eutimia paladar. -

ITINERARY – Santiago De Cuba Embarkation *Exclusive to Hola Sun Holidays* (Santiago De Cuba/Havana/Cienfuegos/Montego Bay (Jamaica))

ITINERARY – Santiago de Cuba Embarkation *Exclusive to Hola Sun Holidays* (Santiago de Cuba/Havana/Cienfuegos/Montego Bay (Jamaica)) Day 1 (Thursday): Arrival into Santiago de Cuba Airport. Overnight in Brisas Sierra Mar (standard gardenview room) Day 2 (Friday): Overnight in Brisas Sierra Mar (standard gardenview room) Day 3 (Saturday): Transfer to the Cruise Terminal in Santiago de Cuba. Check in at Celestyal Cruise. Depart Santiago de Cuba Day 4 (Sunday): At Sea Day 5 (Monday): Overnight Havana (Cuba) Day 6 (Tuesday): Departing Havana (Cuba) Day 7 (Wednesday): At Sea Day 8 (Thursday): Cienfuegos (Cuba) Day 9 (Friday): Montego Bay (Jamaica) Day 10 (Saturday): Return to Santiago de Cuba (Cuba). Check out and transfer to Brisas Sierra Mar Day 11 (Sunday) Brisas Sierra Mar (standard gardenview room) Day 12 (Monday): Transfer to the airport for return flight Holguin/Toronto PACKAGE INCLUDES: Round trip airfare from Toronto to Santiago de Cuba and from Holguin to Toronto • Pre/post Santiago de Cuba hotel (AI- meal plan) • Land transfers • 7 Nights Cruise Accommodation (AI- meal plan) • Onboard meals consisting of breakfast/lunch/dinner and afternoon tea • Unlimited alcoholic and non alcoholic beverage package* (gold package for adults and white/silver package which varies for kids 2 to 18yrs) • Ship gratuities • 4 excursions • 2nd Tourist card for re-entry to Cuba • Port taxes (included in the departure taxes) • Representation services *Upgraded beverage packages are available for purchase onboard NOT INCLUDED: Travel documents and visas -

Cuba Educational Travel Havana – Cienfuegos – Pinar Del Rio Educational Trip Draft October 22 – October 30. 2013

Cuba Educational Travel Havana – Cienfuegos – Pinar del Rio Educational Trip Draft October 22 – October 30. 2013 Day 1 – October 22, 2013 *** Arrive in Miami and check-in at the Crowne Plaza Hotel the night before Day 2 – October 23, 2013 *** Depart Miami at 10 am, arriving in Cienfuegos at 11 am Proceed to the Hotel Union , Cienfuegos’ finest hotel, located in the city’s center Following check-in we will do a quick overview of agenda , discussion of current events, what you need to know about the trip to get everyone up to speed about our upcoming week in Cuba Lunch at Palacio del Valle restaurant . This stunning palace, completed in 1917 by a sugar merchant, was once a casino and is now the home of a picturesque restaurant with a sea view. Cuba overview briefing by Collin Laverty , Cuba Educational Travel President Walking tour of historic center of Cienfuegos led by the City Historian’s office Afternoon visit to the Maroya Gallery to meet with owner Miguel Ángel Rodríguez and local artists who have organized and promoted their art internationally through this community gallery. Discussion with young artists about their work and their plans and visions for the future Music and cocktails with the local chapter of UNEAC, the National Union of Artists and Writers of Cuba, featuring an interactive discussion with photographers, musicians and other locals, followed by live music and dance Dinner as a group at a local paladar Day 3 – October 24, 2013 Day trip to Trinidad , a UNESCO world heritage site, known for its cobble stoned streets, pastel colored homes and small-town feel City Tour with Nancy Benítez , a local architect, historian and restoration specialist Conversation with artist Yami Martínez at her gallery, La Casa de los Conspiradores. -

02 February 2021 Province Where to Do the PCR Test Address Pinar Del

02 February 2021 List of places to do PCR in Cuba Notice that at the moment is not possible to do PCR test nor fast (antigen) test, up on departure at the International Airport Jose Martí in Havana. Province Where to do the PCR test Address Pinar del Rio Hotel Pinar del Rio, Medical Service of the Hotel Martí Final Street. Pinar del Rio International Clinic Siboney No. 20005, 11th Avenue, between 200th & 202nd Street. Siboney. Havana Havana, Mayabeque, Artemisa International Clinic Camilo Cienfuegos Linea Street, between L & M. Vedado. Havana International Clinic Varadero Between 60th Street & 1st Avenue. Varadero Matanzas Medical Service of the Hotel (15 Hotels) Varadero Cienfuegos International Clinic Cienfuegos No. 3705, 10th Avenue, between 37th & 39th Street. Cienfuegos Villa Clara Optica Miramar Santa Clara No. 106, Colón Street, between Candelaria & San Migue. Santa Clara International Clinic Trinidad Trinidad Sancti Spíritus CPH Vectores Frank País Street, corner to Bartolomé Masó. Sancti Spíritus Sede Sucursal SMC No. 74, Joaquín Agüero Street, between Abrán Hidalgo & Narciso López Ciego de Ávila Clinic Cayo Coco Cayo Coco. Jardínez del Rey Medical Service of the Hotel (9 Hotel) Cayo Coco. Jardínez del Rey Camaguey Laboratory of Hygiene and Epidemiology , Pino 3 Cisnero Street, between Martí & San Ramón Street. Camaguey Las Tunas Provincial Center of Hygiene and Epidemiology No. 12, Lucas Ortiz Street, corner to Máximo Gómez Street. Las Tunas Optica Miramar Holguín Frexes Street, between Martí & Maceo Street. Holguín Holguín International Clinic Guardalavaca Guardalavaca Granma Provincial Center of Hygiene and Epidemiology Céspedes Street, between Figueredo & Lora Street. Bayamo Santiago de Cuba Provincial Center of Hygiene and Epidemiology No. -

La Habana, Santiago De Cuba, Holguín, Trinidad, Cienfuegos Y Varadero, Circuito Con Estancia En Playa

Cuba: La Habana, Santiago de Cuba, Holguín, Trinidad, Cienfuegos y Varadero, circuito con estancia en playa Cuba: La Habana, Santiago de Cuba, Holguín, Trinidad, Cienfuegos y Varadero Circuito con estancia en playa, 13 días Cuba, rumbo al paraíso Emprende un fascinante viaje de catorce días que te llevará a visitar encantadoras ciudades como La Habana, Santiago de Cuba, Holguín y Trinidad, a perderte en una naturaleza de ensueño y a conocer hondas tradiciones que se transmiten de generación en generación. Y para descansar y disfrutar de la vida sin prisas y bajo el sol, nada mejor que las paradisiacas playas de Varadero. Baila al son cubano, degusta la deliciosa gastronomía criolla y siéntete parte de este histórico país. ¡Viaja a Cuba y descubre todo lo que te hemos preparado! 05/10/2020 2 Cuba: La Habana, Santiago de Cuba, Holguín, Trinidad, Cienfuegos y Varadero, circuito con estancia en playa CUBA: LA HABANA, SANTIAGO DE CUBA, HOLGUÍN, TRINIDAD, CIENFUEGOS Y VARADERO, CIRCUITO CON ESTANCIA EN PLAYA Descubre ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad, playas paradisiacas y paisajes de contrastes Comenzamos nuestro viaje en la capital cubana, explorando a pie la encantadora y colonial Habana Vieja, cuajada de lugares únicos como la Catedral, el Palacio de los Capitanes Generales, el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, entre otros. Al atardecer, nos sorprenderá la ciudad moderna de La Habana, que nos ofrece el lado más actual de una de las urbes más bellas del mundo. Sus museos, playas y su romántico Malecón conviven con el Capitolio, la Plaza de la Revolución... Más tarde pondremos rumbo a Santiago de Cuba, la segunda ciudad más grande de la isla. -

Elsa No Provocó Daños Significativos De Guantánamo a Cienfuegos

Elsa no provocó daños significativos de Guantánamo a Cienfuegos Sobre el impacto de la tormenta tropical en la región occidental, por donde avanzó en la tarde y la noche de este lunes, se conocerá más hoy. Reunión conjunta del Grupo temporal de trabajo del Gobierno para la prevención y control de la COVID-19 y el Órgano económico-social del Consejo de Defensa Nacional René Tamayo León, 5 de Julio de 2021 El paso de la tormenta tropical Elsa por la costa sur del archipiélago y su influencia en las zonas montañosas no dejó daños mayores de Guantánamo a Cienfuegos,al contrario, las lluvias dejadas son positivas, una garantía presente y a futuro para el consumo de la población y el uso agropecuario. Sus efectos sobre la región occidental, que el evento meteorológico atravesó en la tarde y la noche de este lunes, sin embargo, aún están por evaluar. La información la ofrecieron las gobernadoras y gobernadores de las 15 provincias y las autoridades del municipio especial Isla de la Juventud —en videoconferencia—durante la reunión conjunta de este lunes del Grupo temporal de trabajo del Gobierno para la prevención y control de la COVID-19 y el Órgano económico-social del Consejo de Defensa Nacional (CDN). El encuentro fue encabezado por el Primer Secretario del Partido Comunista de Cuba y Presidente de la República, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez; el primer ministro, Manuel Marrero Cruz; y el presidente de la Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular, Esteban Lazo Hernández, todos miembros del Buró Político del Comité Central del Partido. Participaron además el vicepresidente de la República, Salvador Valdés Mesa; y Roberto Morales Ojeda, secretario de Organización y Política de Cuadros del Comité Central, ambos también integrantes del máximo órgano de dirección partidista. -

Experience Cuba Tours Grande 15 Days

Cuba is not a holiday, it’s an Experience! GRANDE - 15 Days Small Group Tour - Escorted Program Your Experts in Tailor Made Cuba Tours experiencecubatours.com.au [email protected] 1300 79 55 31 Travel as part of a small group of up to 7 PAX maximum. Come and experience Cuba; a place where time appears to have stood still. Enjoy not just the old American cars in the streets or the colonial architecture in Old Havana, feel the sense that the world of modern tourism has somehow largely bypassed the Caribbean’s largest island. Cuba is one of the few remaining communist countries in the world. Its isolation from the modern world has perhaps helped to conserve the Cuban society’s personality where you can feel like “the pulsating heart of what it means to be Latino”, with music, dance, and the fiesta being core. Come and Experience Cuba: an undeniably fascinating and unique destination. Starting Days: Sunday End Days: Sunday Inclusions: o Personalised welcome and greeting at Havana airport by ECT representative. Transfers from Havana airport on arrival. Transfers from Havana airport on arrival. o Domestic flight from Santiago de Cuba to Havana. * o Twin share comfort accommodation in "casas particulares" (guesthouses or home-stays) with private bathrooms/ensuites and air-conditioning. ** o Daily breakfasts. o Transfers as specified below. *** o Same private local Cuban guide throughout. o Activities/excursions as specified below. o Travelers Information Package with lots of practical advice (PDF). o Cuba Tourist Map, advised by MINTUR, Minister of Tourism in Cuba. **** o All ECT personnel tips. -

Emma Pask Jazz Festival Tour Havana – Matanzas - Trinidad - Cienfuegos January 15Th – 26Th

Emma Pask Jazz festival Tour Havana – Matanzas - Trinidad - Cienfuegos January 15th – 26th 1 DAY ONE: Tuesday, 15th January , 2019 ( D ) Arrive Havana Cuba, clear customs and meet your tour-manager who will escort you to your waiting coach and transfer to Havana (approx. 30 minutes) Check into your Hotel. Enjoy late afternoon drinks in the gardens of the Hotel Nacional. Dinner in local restaurant. DAY TWO: Wednesday 16thth January - HAVANA (B,L,D) Morning Breakfast in hotel. After breakfast, depart by coach for a sightseeing tour of Old Havana Visit to the Museum of the Revolution and walk down the famous Prado where local artists and dancers gather on weekends for public exhibitions. Lunch in Old Havana in a local cafe Afternoon Continue with the sightseeing tour of Havana. Return to your hotel. Enjoy an optional salsa lesson with professional Cuban salsa teachers. ($15US per person) Evening Free to explore your own dinner options. After dinner enjoy the first night of the Havana International Jazz Festival 2 DAY THREE: Thursday 17th January - HAVANA (B) Morning Breakfast in hotel Travel by coach to the home of the National Choir. This is one of the world’s truly great choirs and you will have the opportunity to catch an impromptu concert. After drop into the National Circus School where many of Cuba’s exceptional circus performers are trained. Afternoon free to explore Havana or catch some performances at the Havana International Jazz Festival. Explore your own lunch and dinner options Evening After dinner attend performances at the Havana International Jazz Festival. OR Visit the 17th century Moro Fort overlooking Havana for the famous Canon Ceremony.