A Tale of Two Crocoducks: Creationist Misuses of Molecular Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J

ISSN 00310301, Paleontological Journal, 2013, Vol. 47, No. 11, pp. 1270–1281. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2013. The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J. K. O’Connora and N. V. Zelenkovb aKey Laboratory of Evolution and Systematics, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, 142 Xizhimenwai Dajie, Beijing China 10044 bBorissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya ul. 123, Moscow, 117997 Russia email: [email protected], [email protected] Received August 6, 2012 Abstract—Since the last description of the ornithurine bird Ambiortus dementjevi from Mongolia, a wealth of Early Cretaceous birds have been discovered in China. Here we provide a detailed comparison of the anatomy of Ambiortus relative to other known Early Cretaceous ornithuromorphs from the Chinese Jehol Group and Xiagou Formation. We include new information on Ambiortus from a previously undescribed slab preserving part of the sternum. Ambiortus is superficially similar to Gansus yumenensis from the Aptian Xiagou Forma tion but shares more morphological features with Yixianornis grabaui (Ornithuromorpha: Songlingorni thidae) from the Jiufotang Formation of the Jehol Group. In general, the mosaic pattern of character distri bution among early ornithuromorph taxa does not reveal obvious relationships between taxa. Ambiortus was placed in a large phylogenetic analysis of Mesozoic birds, which confirms morphological observations and places Ambiortus in a polytomy with Yixianornis and Gansus. Keywords: Ornithuromorpha, Ambiortus, osteology, phylogeny, Early Cretaceous, Mongolia DOI: 10.1134/S0031030113110063 1 INTRODUCTION and articulated partial skeleton, preserving several cervi cal and thoracic vertebrae, and parts of the left thoracic Ambiortus dementjevi Kurochkin, 1982 was one of girdle and wing (specimen PIN, nos. -

Trophic Shift and the Origin of Birds

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.18.256131; this version posted August 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Title: Trophic shift and the origin of birds Author: Yonghua Wu Affiliations: 1School of Life Sciences, Northeast Normal University, 5268 Renmin Street, Changchun, 130024, China. 2Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Animal Resource Conservation and Utilization, Northeast Normal University, 2555 Jingyue Street, Changchun, 130117, China. * Corresponding author: Yonghua Wu, Ph.D Professor, School of Life Sciences Northeast Normal University 5268 Renmin Street, Changchun, 130024, China Tel: +8613756171649 Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.18.256131; this version posted August 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Abstract Birds are characterized by evolutionary specializations of both locomotion (e.g., flapping flight) and digestive system (toothless, crop, and gizzard), while the potential selection pressures responsible for these evolutionary specializations remain unclear. Here we used a recently developed molecular phyloecological method to reconstruct the diets of the ancestral archosaur and of the common ancestor of living birds (CALB). Our results showed that the ancestral archosaur exhibited a predominant Darwinian selection of protein and fat digestion and absorption, whereas the CALB showed a marked enhanced selection of carbohydrate and fat digestion and absorption, suggesting a trophic shift from carnivory to herbivory (fruit, seed, and/or nut-eater) at the archosaur-to-bird transition. -

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 58, Number 4, Pp

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, volume 58, number 4, pp. 605–622 doi:10.1093/icb/icy088 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM INTRODUCTION The Temporal and Environmental Context of Early Animal Evolution: Considering All the Ingredients of an “Explosion” Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/58/4/605/5056706 by Stanford Medical Center user on 15 October 2018 Erik A. Sperling1 and Richard G. Stockey Department of Geological Sciences, Stanford University, 450 Serra Mall, Building 320, Stanford, CA 94305, USA From the symposium “From Small and Squishy to Big and Armored: Genomic, Ecological and Paleontological Insights into the Early Evolution of Animals” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology, January 3–7, 2018 at San Francisco, California. 1E-mail: [email protected] Synopsis Animals originated and evolved during a unique time in Earth history—the Neoproterozoic Era. This paper aims to discuss (1) when landmark events in early animal evolution occurred, and (2) the environmental context of these evolutionary milestones, and how such factors may have affected ecosystems and body plans. With respect to timing, molecular clock studies—utilizing a diversity of methodologies—agree that animal multicellularity had arisen by 800 million years ago (Ma) (Tonian period), the bilaterian body plan by 650 Ma (Cryogenian), and divergences between sister phyla occurred 560–540 Ma (late Ediacaran). Most purported Tonian and Cryogenian animal body fossils are unlikely to be correctly identified, but independent support for the presence of pre-Ediacaran animals is recorded by organic geochemical biomarkers produced by demosponges. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

UNDENIABLE the Survey of Hostility to Religion in America

UNDENIABLE The Survey of Hostility to Religion in America 2014 Edition Editorial Team Kelly Shackelford Chairman Jeffrey Mateer Executive Editor Justin Butterfield Editor-in-chief Michael Andrews Assistant Editor Past Contributors Bryan Clegg An Open Letter to the American PEople UNDENIABLE To our fellow citizens: The Survey of Hostility to Religion in America Hostility to religion and religious freedom in America—institutional, pervasive, damaging hostility—can no longer reasonably be denied. And 2014 Edition yet there remain deniers. Because denial of these attacks is a mortal threat to the survival and health of Kelly Shackelford, chairman our republic, Liberty Institute and Family Research Council collaborated in 2012 to publish a survey documenting the frequency and severity of incidents Jeffrey Mateer, executive editor of hostility. In the 2013 survey entitled Undeniable, the research team led by Justin Butterfield, editor-in-chief a Harvard-trained constitutional attorney found almost twice the number of incidents in the previous twelve months than all the incidents found from Michael Andrews, assistant editor several years’ past. The rate of hostility was increasing at an alarming rate. This year in Undeniable: The Survey of Hostility to Religion 2014, the team Copyright © 2013–2014 Liberty Institute. of researchers again documented an alarming increase in the number of All rights reserved. hostile incidents toward religion from the year before. The rate of hostility is continuing to climb. We offer Undeniable 2014 to you, the American people, as an alarm bell This publication is not to be used for legal advice. Because the law is ringing in the night. We believe the many public opinion surveys showing constantly changing and each factual situation is unique, Liberty Institute that you, the people, are still a religious people. -

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: a User's Guide for Paleontologists

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: A User’s Guide for Paleontologists Laura C. Soul - Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA David F. Wright - Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024, USA and Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA Abstract. Recent advances in statistical approaches called Phylogenetic Comparative Methods (PCMs) have provided paleontologists with a powerful set of analytical tools for investigating evolutionary tempo and mode in fossil lineages. However, attempts to integrate PCMs with fossil data often present workers with practical challenges or unfamiliar literature. In this paper, we present guides to the theory behind, and application of, PCMs with fossil taxa. Based on an empirical dataset of Paleozoic crinoids, we present example analyses to illustrate common applications of PCMs to fossil data, including investigating patterns of correlated trait evolution, and macroevolutionary models of morphological change. We emphasize the importance of accounting for sources of uncertainty, and discuss how to evaluate model fit and adequacy. Finally, we discuss several promising methods for modelling heterogenous evolutionary dynamics with fossil phylogenies. Integrating phylogeny-based approaches with the fossil record provides a rigorous, quantitative perspective to understanding key patterns in the history of life. 1. Introduction A fundamental prediction of biological evolution is that a species will most commonly share many characteristics with lineages from which it has recently diverged, and fewer characteristics with lineages from which it diverged further in the past. This principle, which results from descent with modification, is one of the most basic in biology (Darwin 1859). -

A Second Cretaceous Ornithuromorph Bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, Northwestern China Author(S): Hai-Lu You , Jessie Atterholt , Jingmai K

A Second Cretaceous Ornithuromorph Bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, Northwestern China Author(s): Hai-Lu You , Jessie Atterholt , Jingmai K. O'Connor , Jerald D. Harris , Matthew C. Lamanna and Da-Qing Li Source: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 55(4):617-625. 2010. Published By: Institute of Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2009.0095 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.4202/app.2009.0095 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. A second Cretaceous ornithuromorph bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, northwestern China HAI−LU YOU, JESSIE ATTERHOLT, JINGMAI K. O’CONNOR, JERALD D. HARRIS, MATTHEW C. LAMANNA, and DA−QING LI You, H.−L., Atterholt, J., O’Connor, J.K., Harris, J.D., Lamanna, M.C., and Li, D.−Q. 2010. A second Cretaceous ornithuromorph bird from the Changma Basin, Gansu Province, northwestern China. -

Cognition, Biology and Evolution of Musicality Rstb.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Henkjan Honing1, Carel Ten Cate2, Isabelle Peretz3 and Sandra E

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on February 2, 2015 Without it no music: cognition, biology and evolution of musicality rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org Henkjan Honing1, Carel ten Cate2, Isabelle Peretz3 and Sandra E. Trehub4 1Amsterdam Brain and Cognition (ABC), Institute for Logic, Language and Computation (ILLC), University of Amsterdam, PO Box 94242, 1090 CE Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2Institute of Biology Leiden (IBL), Leiden Institute for Brain and Cognition (LIBC), Leiden University, Introduction PO Box 9505, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands 3Center for Research on Brain, Language and Music and BRAMS, Department of Psychology, University of Cite this article: Honing H, ten Cate C, Peretz Montreal, 1420 Mount Royal Boulevard, Montreal, Canada H3C 3J7 4 I, Trehub SE. 2015 Without it no music: Department of Psychology, University of Toronto Mississauga, 3359 Mississauga Road, Mississauga, Canada L5L 1C6 cognition, biology and evolution of musicality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370: 20140088. Musicality can be defined as a natural, spontaneously developing trait based http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0088 on and constrained by biology and cognition. Music, by contrast, can be defined as a social and cultural construct based on that very musicality. One contribution of 12 to a theme issue One critical challenge is to delineate the constituent elements of musicality. What biological and cognitive mechanisms are essential for perceiving, appre- ‘Biology, cognition and origins of musicality’. ciating and making music? Progress in understanding the evolution of music cognition depends upon adequate characterization of the constituent mechan- Subject Areas: isms of musicality and the extent to which they are present in non-human behaviour, evolution, cognition, neuroscience, species. -

The Origin and Early Evolution of Dinosaurs

Biol. Rev. (2010), 85, pp. 55–110. 55 doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00094.x The origin and early evolution of dinosaurs Max C. Langer1∗,MartinD.Ezcurra2, Jonathas S. Bittencourt1 and Fernando E. Novas2,3 1Departamento de Biologia, FFCLRP, Universidade de S˜ao Paulo; Av. Bandeirantes 3900, Ribeir˜ao Preto-SP, Brazil 2Laboratorio de Anatomia Comparada y Evoluci´on de los Vertebrados, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’, Avda. Angel Gallardo 470, Cdad. de Buenos Aires, Argentina 3CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas y T´ecnicas); Avda. Rivadavia 1917 - Cdad. de Buenos Aires, Argentina (Received 28 November 2008; revised 09 July 2009; accepted 14 July 2009) ABSTRACT The oldest unequivocal records of Dinosauria were unearthed from Late Triassic rocks (approximately 230 Ma) accumulated over extensional rift basins in southwestern Pangea. The better known of these are Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis, Pisanosaurus mertii, Eoraptor lunensis,andPanphagia protos from the Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina, and Staurikosaurus pricei and Saturnalia tupiniquim from the Santa Maria Formation, Brazil. No uncontroversial dinosaur body fossils are known from older strata, but the Middle Triassic origin of the lineage may be inferred from both the footprint record and its sister-group relation to Ladinian basal dinosauromorphs. These include the typical Marasuchus lilloensis, more basal forms such as Lagerpeton and Dromomeron, as well as silesaurids: a possibly monophyletic group composed of Mid-Late Triassic forms that may represent immediate sister taxa to dinosaurs. The first phylogenetic definition to fit the current understanding of Dinosauria as a node-based taxon solely composed of mutually exclusive Saurischia and Ornithischia was given as ‘‘all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of birds and Triceratops’’. -

ALPHABETICAL LIST of Dvds and Vts 9/6/2011 DVD a Mighty Heart

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF DVDs AND VTs 9/6/2011 DVD A Mighty Heart: Story of Daniel Pearl A Nurse I am – Documentary and educational film about nurses A Single Man –with Colin Firth and Julianne Moore (R) Abe and the Amazing Promise: a lesson in Patience (VeggieTales) Akeelah and the Bee August Rush - with Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams Australia - with Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman Aviator (story of Howard Hughes - with Leonardo DiCaprio Because of Winn-Dixie Beethoven - with Charles Grodin, Bonnie Hunt Big Red Black Beauty Cats & Dogs Changeling - with Angelina Jolie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory - with Johnny Depp Charlie Wilson’s War - with Tom Hanks, Julie Roerts, Phil Seymour Hoffman Charlotte’s Web Chicago Chocolat - with Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin & Johnny Depp Christmas Blessing - with Neal Patrick Harris Close Encounters of the Third Kind – with Richard Dreyfuss Date Night – with Steve Carell and Tina Fey (PG-13) Dear John – with Channing Tatum and Amanda Seyfried (PG-13) Doctor Zhivago Dune Duplicity - with Julia Roberts and Clive Owen Enchanted Evita Finding Nemo Finding Neverland Fireproof – with Kirk Cameron on Erin Bethea (PG) Five People You Meet in Heaven Fluke Girl With a Pearl Earring – with Colin Firth, Scarlett Johannson, Tom Wilkinson Grand Torino (with Clint Eastwood) Green Zone – with Matt Damon (R) Happy Feet Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hildalgo with Viggo Mortensen (PG13) Holiday, The – with Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet, -

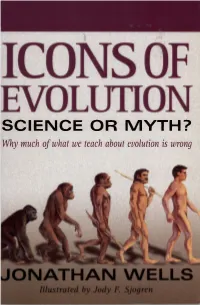

Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution Is Wrong/By Jonathan Wells

ON SCIENCE OR MYTH? Whymuch of what we teach about evolution is wrong Icons ofEvolution About the Author Jonathan Wells is no stranger to controversy. After spending two years in the U.S. Ar my from 1964 to 1966, he entered the University of California at Berkeley to become a science teacher. When the Army called him back from reser ve status in 1968, he chose to go to prison rather than continue to serve during the Vietnam War. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in religious studies at Yale University, where he wrote a book about the nineteenth century Darwinian controversies. In 1989 he returned to Berkeley to earn a second Ph.D., this time in molecular and cell biology. He is now a senior fellow at Discovery Institute's Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (www.discovery.org/ crsc) in Seattle, where he lives with his wife, two children, and mother. He still hopes to become a science teacher. Icons ofEvolution Science or Myth? Why Much oJWhat We TeachAbout Evolution Is Wrong JONATHAN WELLS ILLUSTRATED BY JODY F. SJOGREN IIIIDIDIREGNERY 11MPUBLISHING, INC. An EaglePublishing Company • Washington, IX Copyright © 2000 by Jonathan Wells All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including pho tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. -

Evidence for Design in Physics and Biology: from the Origin of the Universe to the Origin of Life

52 stephen c. meyer Pages 53–111 of Science and Evidence for Design in the Universe. The Proceedings of the Wethersfield Institute. Michael Behe, STEPHEN C. MEYER William A. Dembski, and Stephen C. Meyer (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2001. 2000 Homeland Foundation.) EVIDENCE FOR DESIGN IN PHYSICS AND BIOLOGY: FROM THE ORIGIN OF THE UNIVERSE TO THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 1. Introduction In the preceding essay, mathematician and probability theo- rist William Dembski notes that human beings often detect the prior activity of rational agents in the effects they leave behind.¹ Archaeologists assume, for example, that rational agents pro- duced the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone; insurance fraud investigators detect certain ‘‘cheating patterns’’ that suggest intentional manipulation of circumstances rather than ‘‘natu- ral’’ disasters; and cryptographers distinguish between random signals and those that carry encoded messages. More importantly, Dembski’s work establishes the criteria by which we can recognize the effects of rational agents and distinguish them from the effects of natural causes. In brief, he shows that systems or sequences that are both ‘‘highly com- plex’’ (or very improbable) and ‘‘specified’’ are always produced by intelligent agents rather than by chance and/or physical- chemical laws. Complex sequences exhibit an irregular and improbable arrangement that defies expression by a simple formula or algorithm. A specification, on the other hand, is a match or correspondence between an event or object and an independently given pattern or set of functional requirements. As an illustration of the concepts of complexity and speci- fication, consider the following three sets of symbols: 53 54 stephen c.