CHAPTER 19 a Basic Principle of the Association for the Threefolding of the Social Organism Is to Work Toward an Independent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House Bill 20B-1001

HOUSE BILL 20B-1001 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Young and Soper, Arndt, Benavidez, Bird, Buckner, Buentello, Caraveo, Coleman, Cutter, Duran, Esgar, Exum, Froelich, Garnett, Gonzales-Gutierrez, Gray, Herod, Holtorf, Hooton, Jackson, Jaquez Lewis, Kennedy, Kipp, Kraft-Tharp, Lontine, McCluskie, McLachlan, Melton, Michaelson Jenet, Mullica, Rich, Roberts, Singer, Sirota, Snyder, Sullivan, Tipper, Titone, Valdez A., Valdez D., Weissman, Woodrow, Becker, Will; also SENATOR(S) Donovan and Coram, Bridges, Cooke, Crowder, Danielson, Fenberg, Fields, Foote, Gardner, Ginal, Gonzales, Hansen, Hisey, Holbert, Lee, Lundeen, Moreno, Pettersen, Priola, Rankin, Rodriguez, Scott, Smallwood, Sonnenberg, Story, Tate, Todd, Williams A., Winter, Woodward, Zenzinger, Garcia. CONCERNING SUPPORT FOR EXPANDING BROADBAND ACCESS FOR PRESCHOOL THROUGH TWELFTH GRADE EDUCATION, AND, IN CONNECTION THEREWITH, CREATING THE CONNECTING COLORADO STUDENTS GRANT PROGRAM AND MAKING AN APPROPRIATION. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: SECTION 1. In Colorado Revised Statutes, add article 103 to title 22 as follows: ARTICLE 103 Capital letters or bold & italic numbers indicate new material added to existing law; dashes through words or numbers indicate deletions from existing law and such material is not part of the act. Connecting Colorado Students Grant Program 22-103-101. Legislative declaration. (1) THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY FINDS THAT: (a) THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS LED MANY SCHOOL DISTRICTS AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS DURING THE 2019-20 AND 2020-21 SCHOOL YEARS TO -

Rickford, Angela Eunice

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks The SJSU Emeritus and Retired Faculty Emeritus and Retired Faculty Biographies Association 10-5-2020 Rickford, Angela Eunice San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/erfa_bios Recommended Citation San Jose State University, "Rickford, Angela Eunice" (2020). Emeritus and Retired Faculty Biographies. 330. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/erfa_bios/330 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The SJSU Emeritus and Retired Faculty Association at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emeritus and Retired Faculty Biographies by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURRICULUM VITAE: ANGELA E. RICKFORD Professor, College of Education, San Jose State University One Washington Square, San Jose, CA 95192-0078 408-924-3681 (W); [email protected] PERSONAL African American (US Citizen); married to John, with four children. EMPLOYMENT 2007-present Professor, College of Education, San Jose State University (SJSU). 2002-2007 Associate Professor, College of Education, Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, San Jose State University (SJSU), California. 1996-02 Assistant Professor, College of Education, Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, San Jose State University, San Jose, California. (See page 3 below for courses taught.) 1990-92 Residence Dean, Stanford University. Responsible for the academic counseling, advising, disciplinary and problem-solving functions associated with student affairs Deans. 1981-90 Owner of/teacher in a pre-school facility in the Stanford/Palo Alto area. 1979-80 Founder and Director, Kingston Preschool (enrollment up to 24 preschool children, 3-5 years old), Georgetown, Guyana, South America. -

SHERMAN ALEXIE Indian Education

SHERMAN ALEXIE SHERMAN ALEXIE is a poet, fiction writer, and filmmaker known for witty and frank explorations of the lives of contemporary Native Americans. A Spokane/Coeur d'Alene Indian, Alexie was born in 1966 and grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Wellpinit, Washington. He spent two years at Gonzaga University before transferring to Washington State University in Pullman. The same year he graduated, 1991, Alexie published The Business ofFancydancing, a book of poetry that led the New York Times Book Review to call him "one of the major lyric voices of our time." Since then Alexie has published many more books of poetry, including I Would Steal Horses ( 1993) and One Stick Song (2000); the novels Reservation Blues (1995) and Indian Killer (1996); and the story collections The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven (1993), The Toughest Indian in the World (2000), and Ten Little Indi ans ( 2003). Alexie also wrote and produced Smoke Signals, a film that won awards at the 1998 Sundance Film Festival, and he wrote and directed The Business of Fancydancing (2002), a film about the paths of two young men from the Spokane reservation. Living in Seattle with his wife and children, Alexie occasionally performs as a stand-up comic and holds the record for the most consecutive years as World Heavyweight Poetry Bout Champion. Indian Education Alexie attended the tribal school on the Spokane reservation through the seventh grade, when he decided to seek a better education at an off-reservation :', \ all-white high school. As this year-by-year account of his schooling makes clear, he was not firmly at home in either setting. -

Educational Patterns in Colonial Malaya Author(S): Charles Hirschman Source: Comparative Education Review, Vol

Educational Patterns in Colonial Malaya Author(s): Charles Hirschman Source: Comparative Education Review, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Oct., 1972), pp. 486-502 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Comparative and International Education Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1186779 Accessed: 03-04-2016 19:55 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press, Comparative and International Education Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Comparative Education Review This content downloaded from 128.95.104.109 on Sun, 03 Apr 2016 19:55:58 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms EDUCATIONAL PATTERNS IN COLONIAL MALAYA* CHARLES HIRSCHMAN BACKGROUND MOST "THIRD WORLD" NATIONS share a common past and a similar orientation to the future. Direct rule by the colonial powers of the West has given way to in- dependence only in the last decade or two. Independence has usually been ac- companied by a new emphasis on economic and social development to enhance the welfare of the people. However, the heritage of the past often constrains the future. The influence of the colonial experience upon a nation's economic, po- litical and social institutions continues long after formal independence, often to the detriment of the nation's professed social and economic objectives. -

Pre-Kindergarten Through Twelfth Grade Digital Science Program

ceocfointerviews.com All rights reserved! Issue: February 2, 2015 The Most Powerful Name in Corporate News Pre-Kindergarten through Twelfth Grade Digital Science Program CEOCFO: Dr. Johnson, what is the basic idea behind Accelerate Learning™? Dr. Johnson: Accelerate Learning is a pre kindergarten through twelfth grade digital science program that provides all of the assets a teacher would need to teach science to their students throughout the school year. It is an Online, comprehensive, and hands-on science curriculum for PreK-12 that puts teacher support at its center. CEOCFO: How do teachers typically access material today and why should they be accessing it through Accelerate Learning? Dr. Johnson: They access the curriculum online from any device. Unlike a textbook, we are very dynamic. A textbook is static for eight to ten years, when you buy our product you are buying a product which is continuously updated. Therefore, if Pluto is no longer a planet, our curriculum will reflect the change the very next day, so you are getting a dynamic up to date curriculum. The second thing you are getting is a curriculum that is 100% aligned to your states standards, so it is customized... Our curriculum is written to align to the verb, adjective and noun of the assessments that students must take in order to prove proficiency in the science in their state. Therefore, our customized curriculum gives the assurance to the teacher, parent and the administrators that their students are learning the science that relates directly to the standards that their state has adopted. Dr. Vernon Johnson CEOCFO: How are you able to keep up with the standards and certainly keep up President & CEO with the new scientific information? Dr. -

A Guide for the Placement of Students Presenting Foreign Transcripts

A Guide for the Placement of Students Presenting Foreign Transcripts Allen Altman Board Member, District 1 Marge Whaley Board Chairman, District 2 Cathi Martin Board Member, District 3 Kathryn Starkey Vice Chairman, District 4 Frank Parker Board Member, District 5 Heather Fiorentino Superintendent Sandra S. Ramos Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instructional Services Olga Swinson Chief Finance Officer Renalia Smith DuBose, Esq. Assistant Superintendent for Administration James T. Davis Assistant Superintendent for High, Adult and Alternative Schools Tina Tiede Assistant Superintendent for Middle Schools Ruth B. Reilly Assistant Superintendent for Elementary Schools David Scanga, Ph.D. Executive Director for Elementary Programs Ray Gadd Assistant Superintendent for Support Services The District School Board of Pasco County ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The District School Board of Pasco County wishes to thank The School Board of Broward County, Florida Sayra Velez Hughes Executive Director Multicultural & ESOL Program Services Education Department for permitting the use and distribution of the document A Guide for the Placement of Foreign-Born Students. The guide was developed during the 2006-2007 school year and serves to assist schools in interpreting the transcripts presented by students coming from education systems outside of the United States. Jeff Morgenstein Supervisor for Curriculum and Instructional Services ESOL and World Languages INTRODUCTION The purpose of this guide is to provide teachers, administrators, and guidance counselors with a reference source for interpreting the transcripts presented by students who have been educated in a system outside of the United States. In order to appropriately place students in the grade and program of study commensurate with their prior educational experiences, a clear understanding of how other nations organize their school systems is essential. -

Colorado Standards Alignment Preschool Through Twelfth Grade

Colorado Standards Alignment 2010 Colorado Academic Standards CCSS Supplement, produced by the State Department of Education Preschool through Twelfth Grade Trademark of Renaissance Learning, Inc., and its subsidiaries, registered, common law, or pending registration in the United States and other countries . P.O. Box 8036 • Wisconsin Rapids, WI 54495-8036 Phone: (800) 338-4204 • Fax: (715) 424-4242 www.renlearn.com Colorado Standards Alignment Standards List with Aligned Product Skills The Standards List with Aligned Product Skills Report is a standards-oriented document showing the entire list of standards for the subject, discipline, and grade and the product skills aligned to those standards. This alignment report shows the breadth of standards coverage for the purpose and focus of this product. Note to Educator ................................................................................................... iii Preschool .......................................................................................................... 1 Kindergarten ....................................................................................................... 4 First Grade ........................................................................................................ 12 Second Grade ....................................................................................................... 22 Third Grade ........................................................................................................ 31 Fourth Grade ...................................................................................................... -

Twelfth Grade – Unit Outlines

SUGGESTED UNIT OUTLINES FOR SOCIAL STUDIES GLES 12th GRADE TWELFTH GRADE – UNIT OUTLINES In twelfth grade, students use the conceptual understandings they have developed in civics, economics, geography, and history to explore pressing issues in our world today. The recommended context for this exploration, therefore, focuses on contemporary world issues. By applying their learning from previous years to current topics, students situate current world issues in their historical, geographic, political, economic, and cultural contexts. The cognitive demand of the GLEs is primarily evaluation in an effort to leave these graduating students ready to become the next decision makers and leaders of their communities, the nation, and the world. The following pages provide unit outlines to help you organize a contemporary world problems (or issues) course around the required state standards. These suggested unit outlines are framed around major developments or themes related to these problems and issues. Civics, economics, geography, history, and social studies skills are embedded in this framework. They start with possible essential and guiding questions to help frame the unit. The sample guiding questions focus on the specific issues that connect with the particular era, developments, or themes. The sample essential questions are meant to remind us of how the themes and eras addressed in a particular unit relate to timeless important issues and concepts. Please note that while the GLEs (in bold) are required, the examples are merely suggestions. Since it would be impossible to address all of the important issues and problems the world is facing today, these examples are meant to provide some possible contexts in which to teach these standards. -

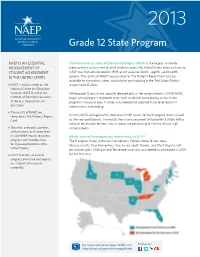

2013 Grade 12 State Program

2013 Grade 12 State Program NAEP IS AN ESSENTIAL The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is the largest nationally MEASUREMENT OF representative assessment of what students across the United States know and can do. STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT NAEP was first administered in 1969, and it assesses fourth-, eighth-, and twelfth- IN THE UNITED STATES. graders. The results of NAEP are published as The Nation’s Report Card and are available for the nation, states, and districts participating in the Trial Urban District NAEP is administered by the Assessment (TUDA). National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) within the While grade 12 results are typically released only at the national level, in 2009, NCES Institute of Education Sciences began a trial program to provide state-level results for participating states. In the of the U.S. Department of program’s inaugural year, 11 states volunteered and received state-level results in Education. mathematics and reading. The results of NAEP are released as The Nation’s Report In 2013, NCES will again offer state-level NAEP results for the 11 original states as well Card. as two new participants. The results from the assessment will provide 13 states with a national benchmark for how their students are performing at the end of their high Teachers, principals, parents, school careers. policymakers, and researchers all use NAEP results to assess Which states will participate and receive results in 2013? progress and develop ways The 11 original states, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, to improve education in the Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, South Dakota, and West Virginia, will United States. -

A Study of US Eighth Grade Mathematics

PURSUING EXCELLENCE ___ A STUDY OF U.S. EIGHTH-GRADE MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE TEACHING, LEARNING, CURRICULUM, AND ACHIEVEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT ___ INITIAL FINDINGS FROM THE THIRD INTERNATIONAL MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE STUDY 1 U.S. Department of Education Richard W. Riley Secretary Office of Educational Research and Improvement Sharon P. Robinson Assistant Secretary National Center for Education Statistics Pascal D. Forgione, Jr. Commissioner of Education Statistics National Center for Education Statistics The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing, and reporting data related to education in the United States and other nations. It fulfills a congressional mandate to collect, collate, analyze, and report full and complete statistics on the condi- tion of education in the United States; conduct and publish reports and specialized analyses of the meaning and significance of such statistics; as- sist state and local education agencies in improving their statistical sys- tems; and review and report on education activities in foreign countries. NCES activities are designed to address high priority education data needs; provide consistent, reliable, complete, and accurate indicators of education status and trends; and report timely, useful, and high quality data to the U.S. Department of Education, the Congress, the states, other education policymakers, practitioners, data users, and the general public. We strive to make our products available in a variety of formats and in lan- guage that is appropriate to a variety of audiences. You, as our customer, are the best judge of our success in communicating information effectively. If you have any comments or suggestions about this or any other NCES product or report, we would like to hear from you. -

Part I: Migrant Summer Program Intent to Participate Pre-K – Twelfth Grade and Part II: Migrant Summer Program Intent to Participate Birth to 2

FY Part I: Migrant Summer Program Intent to Participate Pre-K – Twelfth Grade and Part II: Migrant Summer Program Intent to Participate Birth to 2 County-District Code County-District Name Superintendent Name & Signature Date Yes, the district will provide a FY Summer Program for migrant students. Part I Part II No, the district will not provide a FY Summer Program for migrant students. Part I Part II Please do not complete the application(s) below, if responding NO to Part I and Part II. Part I: Migrant Summer Program Plan Pre-K through Twelfth Grade Summer Program Director or Contact Person: Phone Number: Email Address: Facility/Building where program will be held: Address: City: Zip Code: Anticipated total number of students to be served: Length of Program: DAYS: Hours: to Program Dates: START: END: Participating in Summer Food Program: Yes No Estimated cost of the instruction Migrant Summer Program (excluding transportation): $ Estimated cost of transportation for the Migrant Summer Program: $ Part I: Total Number of Students Served by Grade Levels Pre-K 4 year olds Fifth grade Pre-K 5 year olds Sixth grade Kindergarten Seventh grade First grade Eighth grade Second grade Ninth grade Third grade Eleventh grade Fourth grade Twelfth grade Oklahoma State Department of Education | Office of Federal Programs | June 2019 Page 1 of 4 Part I: Migrant Summer Program Intent to Participate Pre-K – Twelfth Grade and FY Part II: Migrant Summer Program Intent to Participate Birth to 2 Part I: Total Number of Students Served by Grade Levels 1. How will the District ensure that Identification and Recruitment remain a priority during the summer school session? 2. -

Prek Program Philosophy

Central School “Where Excellence Begins” Dr. Joseph A. Caravela Principal PRE-KINDERGARTEN PROGRAM PHILOSOPHY Pre-kindergarten is recognized as part of a comprehensive Pre-K through twelfth grade educational program for students in Glen Ridge. The Pre-K children are part of the tradition of excellence in our Glen Ridge public school system. We recognize that growth and development are unique to each child and that children develop skills at different rates, especially in the areas of emergent literacy and mathematics. At no other time in a child’s educational experience does such a wide range of needs, abilities, aptitudes, and interests exist; need to be effectively dealt with in a classroom setting; and fall within such a wide realm of what is developmentally “normal.” Prekindergarten is recognized as the first year of formal schooling in Glen Ridge. The philosophy of the Glen Ridge Pre-kindergarten is based on the understanding that the early years are crucial to subsequent educational programs. We recognize that the rate of learning and development during these years maximizes each child’s potential; therefore, the learning environment builds upon the opportunity that is inherent in the enthusiasm, openness and readiness of children to absorb new experiences during their formative years. Our fundamental goal is to provide a planned educational environment, rich in learning experiences, so that a positive foundation for the future will be nurtured. We are dedicated to providing those learning experiences that will develop a positive self-image in every child along with the emotional, social, and intellectual skills necessary to be successful in the classroom.