2018 Water Resources Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood History 1. According to Records

Flood History 1. According to records from the NOAA Event Records database, the months when the most flooding occurs are March, with five (5) reported floods from 1950 to present, September, with four (4) reported floods, and January and February both with three (3) reported floods. There have been 29 flood events in Jefferson County since 1993, 18 of which were river floods, 11 that were considered flash flood events. 2. The worst hazard events experienced in Jefferson County were incidents of flooding resulting from heavy rains and snow melt. The earliest flood on record occurred in 1870 when the Shenandoah River was recorded at 12.9 feet above flood stage in the community of Millville. The following are brief descriptions of historical floods that have occurred in Jefferson County. a. October 1962 – Flooding of the Shenandoah River at Millville resulted in estimated damages to over 40 homes and mobile homes. The river crested at 32.45 feet. b. April 22, 1992 – Both the Shenandoah and the Potomac Rivers crested above flood stage after 4.5 inches of rainfall. A car and a mobile home were destroyed by the high waters. c. March 25-28, 1993 – Flash flooding occurred after snow melted throughout the county. Several people were evacuated and approximately $5,000 in damages to public facilities was reported. d. January 19-21, 1996 – A three-day period of flooding resulted from snow melting after the Blizzard of 1996. Several roads were closed and many structures were affected or damaged by the high water. This flooding resulted in approximately $593,000 in damages to public and private facilities. -

The Cacapon Settlement: 1749-1800 31

THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 5 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 The existence of a settlement of Brethren families in the Cacapon River Valley of eastern Hampshire County in present day West Virginia has been unknown and uninvestigated until the present time. That a congregation of Brethren existed there in colonial times cannot now be denied, for sufficient evidence has been accumulated to reveal its presence at least by the 1760s and perhaps earlier. Because at this early date, Brethren churches and ministers did not keep records, details of this church cannot be recovered. At most, contemporary researchers can attempt to identify the families which have the highest probability of being of Brethren affiliation. Even this is difficult due to lack of time and resources. The research program for many of these families is incomplete, and this chapter is offered tentatively as a basis for additional research. Some attempted identifications will likely be incorrect. As work went forward on the Brethren settlements in the western and southern parts of old Hampshire County, it became clear that many families in the South Branch, Beaver Run and Pine churches had relatives who had lived in the Cacapon River Valley. Numerous families had moved from that valley to the western part of the county, and intermarriages were also evident. Land records revealed a large number of family names which were common on the South Branch, Patterson Creek, Beaver Run and Mill Creek areas. In many instances, the names appeared first on the Cacapon and later in the western part of the county. -

State Water Control Board Page 1 O F16 9 Vac 25-260-350 and 400 Water Quality Standards

STATE WATER CONTROL BOARD PAGE 1 O F16 9 VAC 25-260-350 AND 400 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS 9 VAC 25-260-350 Designation of nutrient enriched waters. A. The following state waters are hereby designated as "nutrient enriched waters": * 1. Smith Mountain Lake and all tributaries of the impoundment upstream to their headwaters; 2. Lake Chesdin from its dam upstream to where the Route 360 bridge (Goodes Bridge) crosses the Appomattox River, including all tributaries to their headwaters that enter between the dam and the Route 360 bridge; 3. South Fork Rivanna Reservoir and all tributaries of the impoundment upstream to their headwaters; 4. New River and its tributaries, except Peak Creek above Interstate 81, from Claytor Dam upstream to Big Reed Island Creek (Claytor Lake); 5. Peak Creek from its headwaters to its mouth (confluence with Claytor Lake), including all tributaries to their headwaters; 6. Aquia Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 7. Fourmile Run from its headwaters to the state line; 8. Hunting Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 9. Little Hunting Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 10. Gunston Cove from its headwaters to the state line; 11. Belmont and Occoquan Bays from their headwaters to the state line; 12. Potomac Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 13. Neabsco Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 14. Williams Creek from its headwaters to its confluence with Upper Machodoc Creek; 15. Tidal freshwater Rappahannock River from the fall line to Buoy 44, near Leedstown, Virginia, including all tributaries to their headwaters that enter the tidal freshwater Rappahannock River; 16. -

Road Log of the Geology of Frederick County, Virginia W

Vol. 17 MAY, 1971 No. 2 ROAD LOG OF THE GEOLOGY OF FREDERICK COUNTY, VIRGINIA W. E. Nunan The following road log is a guide to geologic The user of this road log should keep in mind features along or near main roads in Frederick that automobile odometers vary in accuracy. Dis- County, Virginia. Distances and cumulative mile- tances between stops and road intersections ages between places where interesting and repre- should be checked frequently, especially at junc- sentative-lithologies, formational contacts, struc- tions or stream crossings immediately preceding tural features, fossils, and geomorphic features stops. The Frederick County road map of the occur are noted. At least one exposure for nearly Virginia Department of Highways, and the U. S. each formation is included in the log. Brief dis- Geological Survey 7.5-minute topographic maps cussions of the geological features observable at are recommended for use with this road log. the various stops is included in the text. Topographic maps covering Frederick County include Boyce, Capon Bridge, Capon Springs, A comprehensive report of the geology of the Glengary, Gore, Hayfield, Inwood, Middletown, Mountain Falls, Ridge, Stephens City, Stephen- County is presented in "Geology and Mineral Re- son, Wardensville, White Hall, and Winchester. sources of Frederick County" by Charles Butts The route of the road log (Figure 1) shows U. S. and R. S. Edmundson, Bulletin 80 of the Virginia and State Highways and those State Roads trav- Division of Mineral Resources. The publication eled or needed for reference at intersections. has a 1:62,500 scale geologic map in color, which Pertinent place names, streams, and railroad is available from the Division for $4.00 plus sales crossings are indicated. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Base-Flow Yields of Watersheds in the Berkeley County Area, West Virginia

Base-Flow Yields of Watersheds in the Berkeley County Area, West Virginia By Ronald D. Evaldi and Katherine S. Paybins Prepared in cooperation with the Berkeley County Commission Data Series 216 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Evaldi, R.D., and Paybins, K.S., 2006, Base-flow yields of watersheds in the Berkeley County Area, West Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 216, 4 p., 1 pl. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

The Archaeology of Opequon Creek: Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in the Material Culture of an Eighteenth-Century Immigrant Community, Frederick County, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2004 The Archaeology of Opequon Creek: Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in the Material Culture of an Eighteenth-Century Immigrant Community, Frederick County, Virginia Ann Schaefer Persson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Persson, Ann Schaefer, "The Archaeology of Opequon Creek: Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in the Material Culture of an Eighteenth-Century Immigrant Community, Frederick County, Virginia" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626441. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-19rg-4g57 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF OPEQUON C^EEK Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in the Material Culture of an Eighteenth-Century Immigrant Community, Frederick County, Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Ann Schaefer Persson 2004 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Committee, November 2004 rey x Homing, Chair l / j / ________ Norman F. Barka Warren R. -

Table 5-4B: List of Virginia Non-Shellfish NPS TMDL Implementation Planning Projects Through 2019

Table 5-4b: List of Virginia Non-Shellfish NPS TMDL Implementation Planning Projects through 2019 EPA Hydrologic Impairment TMDL IP NAME Approval Impaired Water Unit Cause Year Basin: Atlantic Ocean Coastal Mill Creek, Northampton County NS Mill Creek AO21 Dissolved Oxygen, Mill Creek, Northampton County NS Mill Creek AO21 pH Basin: Albemarle Sound Coastal North Landing Watershed (including Milldam, Middle, West NS West Neck Creek - Middle AS14 Bacteria Neck and Nanney Creeks) North Landing Watershed (including Milldam, Middle, West NS Milldam Creek - Lower AS17 Bacteria Neck and Nanney Creeks) Basin: Big Sandy River Knox Creek and Pawpaw Creek 2013 Knox Creek BS04 Bacteria, 2013 Knox Creek BS04 Sediment 2013 Guess Fork BS05 Bacteria, 2013 Guess Fork BS05 Sediment 2013 Pawpaw Creek BS06 Bacteria, 2013 Pawpaw Creek BS06 Sediment 2013 Knox Creek BS07 Bacteria, 2013 Knox Creek BS07 Sediment Basin: Chesapeake Bay-Small Coastal Piankatank River, Gwynns Island, Milford Haven 2014 Carvers Creek CB10 Bacteria Basin: Chowan River Chowan River Watershed Submitted Nottoway River CU01 Bacteria Submitted Big Hounds Creek CU03 Bacteria Submitted Nottoway River CU04 Bacteria Submitted Carys Creek CU05 Bacteria Submitted Lazaretto Creek CU05 Bacteria Submitted Mallorys Creek CU05 Bacteria Submitted Little Nottoway River CU06 Bacteria Submitted Whetstone Creek CU06 Bacteria Submitted Little Nottoway River CU07 Bacteria Submitted Beaver Pond Creek CU11 Bacteria Submitted Raccoon Creek CU35 Bacteria Three Creek, Mill Swamp, Darden Mill Run 2014 Maclins -

TROUT Stocking – Lakes and Ponds Code No

TROUT Stocking – Lakes and Ponds Code No. Stockings .......Period Code No. Stockings .......Period Code No. Stockings .......Period Q One ...........................1st week of March Twice a month .............. February-April CR Varies ...........................................Varies BW One ........................................... January M One each month ........... February-May One .................................................. May W Two..........................................February MJ One each month ............January-April One ........................................... January One each week ....................March-May Y One ................................................. April BA One each week ...................................... X After April 1 or area is open to public One ...............................................March F weeks of October 19 and 26 Lake or Pond ‒ County Code Lake or Pond ‒ County Code Anawalt – McDowell M Laurel – Mingo MJ Anderson – Kanawha BA Lick Creek – Wayne MJ Baker – Ohio Q Little Beaver – Raleigh MJ Barboursville – Cabell BA Logan County Airport – Logan Q Bear Rock Lakes – Ohio BW Mason Lake – Monongalia M Berwind – McDowell M Middle Wheeling Creek – Ohio BW Big Run – Marion Y Miletree – Roane BA Boley – Fayette M Mill Creek – Barbour M Brandywine – Pendleton BW-F Millers Fork – Wayne Q Brushy Fork – Pendleton BW Mountwood – Wood MJ Buffalo Fork – Pocahontas BW-F Newburg – Preston M Cacapon – Morgan W-F New Creek Dam 14 – Grant BW-F Castleman Run – Brooke, Ohio BW Pendleton – Tucker -

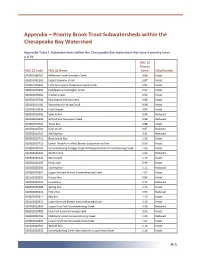

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Mills and Mill Sites in Fairfax County, Virginia and Washington, Dc

Grist Mills of Fairfax County and Washington, DC MILLS AND MILL SITES IN FAIRFAX COUNTY, VIRGINIA AND WASHINGTON, DC Marjorie Lundegard Friends of Colvin Run Mill August 10, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Most of the research for this catalogue of mills of Fairfax County was obtained from the owners, staff members, or neighbors of these mills. I want to thank all these persons who helped in the assembling of the history of these mills. Resource information was also acquired from: the library at the National Park at Great Falls, Virginia; the book, COLVIN RUN MILL, by Ross D. Nether ton; brochures from the Fairfax County Park Authority; and from the staff and Friends of Peirce Mill in the District of Columbia. Significant information on the mill sites in Fairfax County was obtained from the Historic American Building Survey (HABS/HAER) reports that were made in 1936 and are available from the Library of Congress. I want to give special thanks to my husband, Robert Lundegard, who encouraged me to complete this survey. He also did the word processing to assemble the reports and pictures in book form. He designed the attractive cover page and many other features of the book. It is hoped that you will receive as much enjoyment from the reading of the booklet as I had in preparing it for publication. 0 Grist Mills of Fairfax County and Washington, DC Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................... 0 GRIST MILLS of FAIRFAX COUNTY and WASHINGTON, DC ............................................................. -

Opequon Creek Near Martinsburg, West Virginia

Opequon Creek near Martinsburg, West Virginia Latitude: Longitude: Gauge Elevation: Drainage Area: County of Gage: County of Town: Weather Office: 39°25'25" or 39.423611° N 77°56'20" or 77.938889° W 354.33 feet 273 mi2 Berkeley, WV Berkeley, WV Sterling Major Basin: Sub Basin: Minor Sub Basin: Minor: Moderate: Major: Potomac Potomac Potomac 10.00 12.50 15.00 Period of Record (used in flood frequency) Outside Period of Record (not used in flood frequency) 7/23/1947 to Present 1936 to 7/22/1947 Feet Flood Impacts A significant flood is occurring. Numerous homes are flooded east of Martinsburg, along with all of the lower portion of the Stonebridge Golf Club. The worst flooding is south of the 20.00 railroad bridge. To the north of that railroad bridge, flooding is causing less of an impact due to the regulation of flow caused by the railroad line. Water reaches homes on Douglas Grove Road, and may be near a home on Abbie Lane. Hundreds of acres of fields are flooded near the creek. Blairton Road begins to flood, and 15.00 numerous other roads are already flooded and closed. The creek is well out of its banks. Portions of Stonebridge Golf Club are flooded. Golf Course Road /County Road 36/ is flooded near the Stone Bridge. Fields and backyards near the creek 12.50 are flooded and some residents may need to move items to higher ground. Several other roads are flooded, including Grapevine Road, Douglas Grove Road, and Paynes Ford Road. Backwater flooding is occurring on small tributaries, including Tuscarora Creek.