Earth Day 1970-1995: an Information Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bullitt Center Greenest Building Article JAN 2013

http://www.fastcoexist.com/1681160/the-greenest-office-building-in-the-world-is-about-to-open-in- seattle?goback=.gde_1190607_member_203697222#1 The Greenest Office Building In The World Is About To Open In Seattle The Bullitt Center is made from totally clean materials, has composting toilets, and catches enough rainwater to survive a 100-day drought. And it’s 100% solar-powered, in a city not known for its sunny days. Seattle’s Bullitt Center is being heralded as the greenest, most energy-efficient commercial office building in the world. It’s not that the six-story, 50,000-square-foot building is utilizing never-before- seen technology. But it’s combining a lot of different existing technologies and methods to create a structure that’s a showpiece for green design--and a model for others to follow. A project of the Bullitt Foundation, a Seattle-based sustainability advocacy group, the Bullitt Center has an incredibly ambitious goal. From the website: The goal of the Bullitt Center is to change the way buildings are designed, built and operated to improve long-term environmental performance and promote broader implementation of energy efficiency, renewable energy and other green building technologies in the Northwest. Credit: Miller Hull Partnership "The most unique feature of the Bullitt Center is that it’s trying to do everything simultaneously," says Bullitt Foundation President Denis Hayes. "Everything" includes 100% onsite energy use from solar panels, all water provided by harvested rainwater, natural lighting, indoor composting toilets, a system of geothermal wells for heating, and a wood-framed structure (made out of FSC-certified wood). -

Mark Kitchell

A film by Mark Kitchell 101 min, English, Digital (DCP/Blu-ray), U.S.A, 2012, Documentary FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building | 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 | New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 | Fax (212) 989-7649 | [email protected] www.firstrunfeatures.com www.firstrunfeatures.com/fiercegreenfire About the Film A FIERCE GREEN FIRE: The Battle for a Living Planet is the first big-picture exploration of the environmental movement – grassroots and global activism spanning fifty years from conservation to climate change. Directed and written by Mark Kitchell, Academy Award- nominated director of Berkeley in the Sixties, and narrated by Robert Redford, Ashley Judd, Van Jones, Isabel Allende and Meryl Streep, the film premiered at Sundance Film Festival 2012, won acclaim at festivals around the world, and in 2013 begins theatrical release as well as educational distribution and use by environmental groups. Inspired by the book of the same name by Philip Shabecoff and informed by advisors like E.O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy, A FIERCE GREEN FIRE chronicles the largest movement of the 20th century and one of the keys to the 21st. It brings together all the major parts of environmentalism and connects them. It focuses on activism, people fighting to save their homes, their lives, the future – and succeeding against all odds. The film unfolds in five acts, each with a central story and character: • David Brower and the Sierra Club’s battle to halt dams in the Grand Canyon • Lois Gibbs and Love Canal residents’ struggle against 20,000 tons of toxic chemicals • Paul Watson and Greenpeace’s campaigns to save whales and baby harp seals • Chico Mendes and Brazilian rubbertappers’ fight to save the Amazon rainforest • Bill McKibben and the 25-year effort to address the impossible issue – climate change Surrounding these main stories are strands like environmental justice, going back to the land, and movements of the global south such as Wangari Maathai in Kenya. -

Env & Society/F-10.Cwk

SOCI–X235-001 ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIETY (Fall, 2010) Class Time: 3:30-4:45pm, T/R, MO 535 Professor: Dr. Anthony E. Ladd Office: The Department of Sociology, MO 537-D Office Hours: MWR 1:00-3:00pm & by appt. Phone: 865-3640 Email: [email protected] “ Only when the last tree had died and the last river been poisoned and the last fish been caught will we realize that we cannot eat money.” -- Old Cree Indian saying “If we do not change the direction we are going, we will end up where we are headed.” -- Old Chinese Proverb “The price one pays for an environmental education is to live in a world of wounds.” -- Aldo Leopold COURSE DESCRIPTION Environmental Sociology, as a subfield within the larger discipline of sociology, is concerned with the study of the interactions between human societies and the natural environment. As an elective in both the Advanced Common Curriculum and the Environmental Studies Program, this class will help introduce you to the study of environmental history, problems, policies, and controversies from a sociological perspective, but it will also incorporate a number of other academic viewpoints as well. Overall, the readings, lectures, films, and discussion for this class will enable you to become a more informed and critical thinker regarding your relationship to the nature and the future of life on this planet. My aim is to increase not just your knowledge about the world you share, but develop in you the wisdom to envision and practice a way of life which can help to ensure its sustainability. -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

Earth Day 1970-1995: an Information Perspective

Earth Day 1970-1995: An Information Perspective Fred Stoss <[email protected]> Energy, Environment, and Resources Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37932, USA. TEL: 615- 675-9510. "Earth Day is a commitment to make life better, not just bigger and faster; to provide real rather than rhetorical solutions. It is a day to re-examine the ethic of individual progress at mankind's expense. It is a day to challenge the corporate and government leaders who promise change, but who shortchange the necessary programs. It is a day for looking beyond tomorrow. April 22 seeks a future worth living. April 22 seeks a future." Environmental Teach-In Advertisement New York Times January 18, 1970 (1) The celebratory event known as "Earth Day," created in 1969 and 1970, found its initial inspiration in the 1950s and 1960s, decades marked by tremendous social and cultural awareness, times of activism and change. One cultural concept around which millions of people began to rally was the environment. The legacy of environmental thought in the decades prior to the first Earth Day gave birth to the event in 1970. A body of environmental literature emerged in the United States which traced its roots to the colonial and post-Revolutionary War periods. The writings of Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and George Perkins in the latter half of the 19th and in the 20th century stimulated and created a philosophy and ethic for the environment and concerns for nature and the wilderness. The "birth" of the contemporary environmental movement began with the 1949 publication of Aldo Leopold's SAND COUNTRY ALMANAC, considered by many to be one of the most important books on conservation. -

Letter to Frank Stanton, CBS News, from Gaylord Nelson Re: True Origins

,,,,,,nnl!10 r. A . WILLIAMS, .In. , r4.) ., CIIAlnMAH JI .... 1 IlIn r, n IH" O Olr,I, W. VA. JAcon K. JAVITS . N.Y. CI..J\1I10 ,lfll· ,"e LL, n . l. WIN STON L. PRO\lTY. VY. I U W I\U" M . K E NroiCOY, MASS. PETER H. DOMINICK. C01..O. r.I\YLOJl O N eLS O N , WIS . RICHI\RD S . SCHWEIKE R, "A. WI\LTI!H F. M ONOALC, MINN. ROBERT W. PACKWOOD. OREG. ' "U Q MAS F. i!AGLETON, MO. RODERT TAFT. JR •• OHIO I\u\N CRANSTON, CALIfi'. J. GLENN 8EA.L.L. Jft., MD. II.\ROLD E. HUGHE S, IOWA AOI..AJ E. IIl&VENSOH Ill, au... COMMiTTE':: ON . U>.60R ANO PUBl..iC W"C:I..FARE STEWARl' Eo Me CLOR£. frrA"" DIR£CTOIIl RDaERT L NAOL..£., GEN&ftA.L.. COUNaG. WASHiNGTON. D.C. 2.0510 April 7. 1971 Dr. F rank Stanton PRESIDENT Columbia Broadcasting System 530 West 57th Street New York, New Yo.rk 10019 Dear Dr. Stanton: I wish to commend CBS and Walter Cronkite, Daniel Schorr and David Culhane for the valuable contribution to the continuing dialogue on the enviromne...'1.t as repres ented by the Tuesday night program on Earth Day and its impact during the past year. In fact, one of the most important results of Earth Day was not mentioned on the program. It is that CBS and all of the media from TV to. newspapers and n'lagazines are now devoting extensive time and energy to the tas k of educating the nation on the problem. -

A Good Time Was Had by All at the Royal Egg Hunt!

April 2, 2013 A GOOD TIME WAS HAD BY ALL AT THE ROYAL EGG HUNT! Hundreds of residents lined up to enjoy the specially- ordered-great-weather day at the annual Royal Egg Hunt! The children collected eggs galore and then met the Easter Bunny and then proceeded to eat ALL of their candy! Mayor Stermer and Commissioner Norton even joined in the fun! THE CITY OF WESTON · phone 954-385-2000 · facsimile 954-385-2010 The Nation’s Premiere Municipal Corporationsm April 2, 2013 9th ANNUAL FREE CONCERT IN THE PARK WAS A HUGE SUCCESS A huge thank you goes out to the many volunteers, and of course the fans, who attended Saturday night’s 9th Annual Concert in the Park presented by the City of Weston and the Rotary Club of Weston. With Starship featuring Mickey Thomas as the headliner and Christopher Cross as the concert opener, upwards of 5,000 to 7,000 concert-goers enjoyed an extraordinary south Florida night of classic rock. Concert Chair Tom Kallman and Co-Chair Alison Kallman made this giant undertaking look smooth and seamless, and we thank them and the numerous corporate sponsors brought onboard to be able to provide this concert free of charge to the Welcoming the massive community. crowd is our Weston City Mayor Daniel Stermer joined by City Manager John Flint, State Representative Jim Waldman, State Representative Rick Stark, and City Commissioners Jim Norton, Toby Feuer, Tom Kallman and Angel Gomez (separate photo). Christopher Cross entertained the crowd with many of his #1 hits such as “Sailing” and “Ride Like the Wind”. -

Lesson Plan 1 Earth Day 1970 to #Earthdaylive2020—50 Years & a New Era (6:05 Minutes)

#EARTHDAYLIVE Lesson Plan 1 Earth Day 1970 to #EarthDayLive2020—50 Years & A New Era (6:05 minutes) GRADES: 6 and up TIME: 30-60 minutes to several days or more SUBJECT AREAS: Art, Health, Language Arts, Science, and Social Studies/History PURPOSE: To explore advances, gaps, and backslides of the environmental and climate justice movements since the first Earth Day was held 50 years ago on April 22, 1970 and to invite students to engage in Earth Day Live 2020 and other initiatives that will give them opportunities to help envision and create a just, sustainable future. TABLE OF CONTENTS: DESCRIPTION OF THE CONTENT IN THE VIDEO: KEYWORDS/KEY TERMS/KEY HISTORICAL REFERENCES: ● environmental racism—The disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color ● classism—Prejudice against or in favor of people belonging to a particular social class ● farmworkers movement—Through nonviolent tactics such as boycotts, pickets, and strikes, the United Farm Workers (UFW) brought the struggles of farm workers out of the fields and into cities and towns across the country. This movement of farm workers organizing for better pay and safer working conditions has continued to grow since 1962. ● frontline communities—Communities that experience “first and worst” the consequences of climate change and environmental degradation ● Vietnam War protests—The anti-war movement began mostly on college campuses, as members of the leftist organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) began organizing “teach-ins” to express their opposition to the way in which it was being conducted. ● Civil Rights Movement—The civil rights movement was a struggle by African Americans in the mid-1950s to late 1960s to achieve Civil Rights equal to those of whites, including equal opportunity in employment, housing, and education, as well as the right to vote, the right of equal access to public facilities, and the right to be free of racial discrimination. -

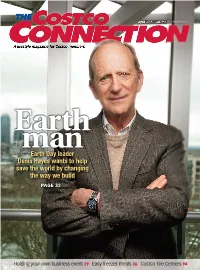

The Costco Connection

Earth man Earth Day leader Denis Hayes wants to help save the world by changing the way we build PAGE 32 Holding your own business event 29 Easy freezer meals 36 CostcoJANUARY 2016 Tire eCenters Costco Connection 94 1 USpC1_Cover_Denis_Hayes_Torrance.indd 1 3/18/16 7:07 AM cover story Environmentalist Denis Hayes creates a living building Building OUR DIGITAL EDITIONS Click here to see Denis Hayes the talking about the Bullitt Center. future (See page 11 for details.) RICK DAHMS By Steve Fisher SUSTAINABILITY. IT’S A word that has was kind of destroying the gorge, clear-cut- pus teach-ins on civil rights and on the war in achieved a high level of visibility and desirabil- ting the forest that I hiked all around in as I Vietnam had created the scenes that ulti- ity worldwide. In a 2012 speech, United Nations was growing up,” he recalls. “I woke up every mately grew into movements around those Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said, “Ours is single morning with a sore throat because of issues. And he thought that might make a world of looming challenges and increasingly uncontrolled sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sense for environmental and conservation limited resources. Sustainable development sulfide [from the mill]. Every now and then issues as well.” offers the best chance to adjust our course.” there’d be a major water-pollution excursion Nelson proposed an environmental Among those at the forefront of sustain- into the Columbia, and you’d look out and teach-in on college campuses in April 1970. able development is Costco member Denis [see] thousands and thousands of dead fish. -

Students Participate in Earth Day by BOB CALVERLEY Society, Who Are Polluting Our Not to Use Water Anywhere With Lion More Each Year

And a neighbor works Students participate in Earth Day By BOB CALVERLEY society, who are polluting our not to use water anywhere with lion more each year. He showed News Staff Wrtier society," he said, "by our at in five miles of shore In Lake students slides of some of the titudes, by the things we buy Erie. anti-pollution facilities In Mid There was just a little bit of . let's not continue to blame —Four thousand people died land. bluish pollution haze where the Dow Chemical when we ride in London in 1952 from air Concerning salt content of the yellow straw fields met the sky on snowmobiles instead of skiing." pollution. river used by Dow In its opera the morning of Earth Day In He called for the young peo — School children In Los tions he said: Clinton County. All over the ple in the audience to change the Angeles don't go outside for re "The quality of the river is country, and In Clinton and St. attitudes toward the environ - cess on days when pollution is better than the quality of drink Johns, people were concerned ment. heavy. ing water of most people In the about that little bit of haze. *You people do have a pro —In Tokyo there are public area." "Much of the younger genera found effect on politics," he said, oxygen masks on many streets, When asked about mercury tion is mad about this situation/ "this generation coming up is a and policement directing traffic contamination of the Great Lakes State Rep. -

Labor Environmentalism

The United Auto Workers and the Emergence of Labor Environmentalism Andrew D. Van Alstyne Assistant Professor of Sociology Southern Utah University Mailing Address: Southern Utah University History, Sociology & Anthropology Department 351 West University Boulevard, CN 225Q Cedar City, UT 84720 Phone: (435) 586-5453 E-mail: [email protected] Andrew D. Van Alstyne is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Southern Utah University. His research focuses on labor environmentalism, urban environmental governance, and sustainability. 1 Abstract Recent collaboration between labor unions and environmental organizations has sparked significant interest in “blue-green” coalitions. Drawing on archival research, this article explores the United Auto Workers (UAW)'s labor environmentalism in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the union promoted a broad environmental agenda. Eventually the union went as far as incorporating environmental concerns in collective bargaining and calling for an end to the internal combustion engine. These actions are particularly noteworthy because they challenged the union’s economic foundation: the automobile industry. However, as a closer examination of the record shows, there was a significant disjuncture between the union’s international leadership, which pushed a broad vision of labor environmentalism, and its rank-and-file membership, which proved resistant to the issue. By the close of the 1970s, the conjunction of economic pressures and declining power in relation to management led the union to retreat from its environmental actions. Keywords: Labor Environmentalism, Blue-Green Coalitions, United Auto Workers, Environmental Justice, Social unionism, Environmental Movements, Historical Sociology 2 Introduction Over the past two decades, in response to long term declines in the labor movement’s size, power, and influence, unions have increasingly turned to building coalitions with other social movements on issues ranging from immigration reform to the minimum wage to environmental protection (Gleeson, 2013; Tattersall, 2010). -

BULLITT CENTER Radiant Cooling and Heating Systems Case Study

Radiant Cooling and Heating Systems Case Study Photos: Miller Hull Partnership OVERVIEW BULLITT CENTER The Bullitt Center in Seattle, Washington is a six-story, 44,700 square foot (SF) Location: Seattle, WA office building. The Bullitt Foundation, a nonprofit philanthropic organization with a Project Size: 52,000 square feet (SF) focus on the environment, worked with local real estate firm Point32 to develop the $32.5 million building. The building was the vision of Denis Hayes to create “the Construction Type: New Construction greenest urban office building in the world” and it received the Sustainable Building Completion Date: 2013 of the Year award from World Architecture News in 2013 and many subsequent Fully Occupied: Yes green building awards. Building Type: Office The Bullitt Building was studied under a California Energy Commission EPIC Climate Zone: 4C research project on radiant heating and cooling systems in 2016-2017. While forced-air distribution systems remain the predominant approach to heating and Totally Building Cost: $32.5 Million | cooling in U.S. commercial buildings, radiant systems are emerging as a part of $625/SF high performance buildings. Radiant systems transfer energy via a surface that contains piping with warmed or cooled water, or a water/glycol mix; this study focused on radiant floor and suspended ceiling panel systems1. These systems can contribute to significant energy savings due to relatively small temperature differences between the room set-point and cooling/heating source, and the efficiency of using water rather than air for thermal distribution2. The full research study included a review of the whole-building design characteristics and site energy use in 23 buildings and surveys of occupant perceptions of indoor environmental quality in 26 buildings with 1645 individuals.