Forum Literary Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 School of Sciences and Mathematics Annual Report 2014‐2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 School of Sciences and Mathematics Annual Report 2014‐2015 Executive Summary The 2014 – 2015 academic year was a very successful one for the School of Sciences and Mathematics (SSM). Our faculty continued their stellar record of publication and securing extramural funding, and we were able to significantly advance several capital projects. In addition, the number of majors in SSM remained very high and we continued to provide research experiences for a significant number of our students. We welcomed four new faculty members to our ranks. These individuals and their colleagues published 187 papers in peer‐reviewed scientific journals, many with undergraduate co‐authors. Faculty also secured $6.4M in new extramural grant awards to go with the $24.8M of continuing awards. During the 2013‐14 AY, ground was broken for two 3,000 sq. ft. field stations at Dixie Plantation, with construction slated for completion in Fall 2014. These stations were ultimately competed in June 2015, and will begin to serve students for the Fall 2015 semester. The 2014‐2015 academic year, marked the first year of residence of Computer Science faculty, as well as some Biology and Physics faculty, in Harbor Walk. In addition, nine Biology faculty had offices and/or research space at SCRA, and some biology instruction occurred at MUSC. In general, the displacement of a large number of students to Harbor Walk went very smoothly. Temporary astronomy viewing space was secured on the roof of one of the College’s garages. The SSM dean’s office expended tremendous effort this year to secure a contract for completion of the Rita Hollings Science Center renovation, with no success to date. -

Featuring Natasha Bedingfield New Album

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LIFEHOUSE RELEASE NEW SINGLE TODAY “BETWEEN THE RAINDROPS” FEATURING NATASHA BEDINGFIELD NEW ALBUM DUE OUT LATER THIS YEAR New York, NY – September 11, 2012 – Geffen Records recording artists Lifehouse return with their first new single in three years: “Between The Raindrops” featuring Natasha Bedingfield. The track is the first single from the band’s forthcoming sixth album and it’s also their first duet. “Between The Raindrops” is available today on iTunes and all other major digital outlets. To hear a sample of the track go to www.lifehousemusic.com Produced by long time collaborator Jude Cole , “Between The Raindrops” features Natasha Bedingfield trading passionate vocals with Lifehouse lead singer Jason Wade . "’Between the Raindrops’ is a confluence of all these different musical styles coming together,” Wade remarked. “There is this cinematic spaghetti western undercurrent breathing and moving in the confines of a pop rock song. The track started as a complete experiment, a sort of stream of consciousness. Over the next few ensuing months Jude and I rewrote the song at least half a dozen times. We brought our friend Jacob Kasher in to help us finish the lyrics. I feel like the song really was solidified and came to life when Natasha came down to the studio and sang on the track." More details on Lifehouse’s forthcoming album will be released in the following weeks. Lifehouse’s multi-platinum 2000 debut, No Name Face , produced “Hanging by a Moment,” a #1 alternative hit which crossed over to become Top 40’s Most Played Song of 2001, while 2002’s Stanley Climbfall solidified the band as a touring force. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

New Songs 1 Vol

platinumkaraoke.ph New Songs 1 Vol. 69 For T-Series DVD ! Blind 16699 Lifehouse The Wild New Songs Bringing Home the Ashes 16668 Swans Seether & 3 Things 16508 Jason Mraz Broken 16572 Amy Lee A Gentle Persuasion 16664 The Camera Bukas Ngayon At Kailanman 16712 fromJerome Walls Abalos The Akala Ko'y Langit 16608 Siakol Bullet With Butterfly Wings 16565 Smashing PumpkinsJessie J ft 2 Akin Ka Na Lang 16671 Vice Ganda Burnin Up 16713 Chainz Kapampanga Aku Na Mu 16584 Business Man 16514 Glock-9 n Hambog ft Ala-Ala Na Lang 16634 Can't Say That I Love You 16651 Nina Lun Stacy Ang Tangi Kong Pangarap 16654 Rico Blanco Can't Stop Thinking About You 16515 Lattisaw Bobby Autumn Of My Life 16513 Centuries 16577 Fall Out Boy Goldsboro Meghan Ave Maria 16571 Beyonce Close Your Eyes 16539 Trainor Awit Para Sa Kanya 16670 True Faith Coco 16619 O.T.Genasis Michael Baby It's Cold Outside 16512 Cool Kids 16693 Echosmith Buble & Idina Bagong Umaga MenzelJulie Ann Could We Gary and Za (Strawberry Lane OST) 16639 16632 San Jose Zsa Bakit Ba Ikaw 16595 Michael Counting Blue Cars 16521 Dishwalla Good Girls 16509 5 Seconds Pangilinan Of Summer Basta't Kasama Ka 16697 Glock 9 ft Crazy 16569 Andrew Good Girls Go Bad 16517 Cobra Lirah Garcia Starship Bermudez Beg For It 16688 Iggy Azalea Creep 16561 Stone Gusto 16579 Jolina Temple Magdangal Pilots Best I Ever Had 16570 Vertical Dalagang Probinsyana 16679 Roel Cortez Habang Buhay 16528 Glenn Horizon Jacinto Between The Raindrops 16589 Lifehouse ft Damang-Dama 16719 Moonstar 88 Halik Sa Hangin 16522 Ebe Dancel Natasha Feat. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

J. D. Thomas Accession

JD THOMAS CULTURAL CENTER, INC. PAST-PERFECT CONTENT INDEX Charles “Madhatter” Collection Series 1: Awards Exhibit/Display Artist: Award: 1. The Fat Boys - “Cruisin” Platinum Sales Award 2. Jodici -“Forever My Lady” Multi-Platinum Sales Award 3. Levert -“The Big Throwdown” Gold Sales Award 4. M.C. Hammer -“Let’s Get it Started” Platinum Sales Award 5. Southern M.U.S.I.C. “Butterball Friendship Award” 6. Charles “MadHatter” Merritt Framed charcoal portrait 7. Charles “MadHatter” Merritt Self Photo 8. Charles “MadHaatter” Merritt Self Photo 9. Blues & Soul Blues Summit Honorium Award 10. Jasmine Guy - Actress Photo to MadHatter *(autographed) Box 1: Artist: Album: 1. Bobby Brown My Prerogative 2. New Edition Christmas All Over the World 3. Bobby Brown Every Little Hit 4. New Edition Heart Break 5. Lou Rawls Let Me Be Good To You 6. Lou Rawls At Last 7. Lou Rawls Live at the Mark Hellinger Theatre, NYC 8. Commodores Caught in the Act 9. Commorores Brick House 10. Commodores Rock Solid Box 2: Artist: Album: 1. L.L. Cool J I’m That Type of Guy 2. Nancy Wilson A Lady With A Song 3. ‘LaBelle & The Bluebells Merry Christmas From LaBelle 4. Myrna Summers/Rev. Wright We’re Going To Make It 5. Shirley Caesar I Remember Mama 6. Hannibal Visions of a New World 7. Manhattans Love Talk 8. St. Augustine’s College Choir The Divine Service 9. Lou Rawls Family Reunion 10. Hall & Oates Live at the Apollo (with David Ruffin & Eddie Kendricks) Box 3: Artist: Album: 1. Glady’s Knight LIFE 2. -

SHOULD EXPERIENCE LIFEHOUSE Turlock, CA

For more information contact: Adrenna Alkhas Marketing and Communication Director (209) 668-1333 ext. 340 – Office For Immediate Release: March 1, 2018 “YOU AND ME AND ALL OF THE PEOPLE” SHOULD EXPERIENCE LIFEHOUSE Turlock, CA (March 1, 2018) – Lifehouse, the American rock band unlike any other, will be coming to the Stanislaus County Fair this summer. The Stanislaus County Fair welcomes Lifehouse, Wednesday, July 18, 2018. The performance will take place on the Bud Light Variety Free Stage at 8:30 p.m. The concert will be hosted by KHOP @ 95.1 and is free with the price of Fair admission. “Lead vocalist, Jason Wade, has such a unique, low-sounding voice that is easy to get lost in,” said Adrenna Alkhas, spokesperson for the Stanislaus County Fair. “Those who listened to them in the early 2000s are definitely in for a nostalgic treat.” With songs in the top 10 of Billboard’s Hot 100, Alternative, Adult Top 40, Mainstream Top 40, Adult Contemporary and Adult Pop charts, Lifehouse has proven their versatility and longevity. It was in 2001 when the Los Angeles-based band first broke through in a big way when “Hanging by a Moment,” from No Name Face, spent 20 weeks in Billboard’s top 10, and won a Billboard Music Award for “Hot 100 Single of the Year.” Since then, the band has released six more albums, three of which also made Billboard’s top 10, sold over 15 million records worldwide and spun off such hit singles as “You and Me,” “First Time,” “Whatever it Takes,” “Broken,” “Halfway Gone,” “Between the Raindrops” and “Hurricane.” Lifehouse has also played to sold-out shows around the globe throughout their 17-year career. -

Push Your Threshold

ICI/PRO Audio PROfile #254 PUSH YOUR THRESHOLD It never gets easier, you just go faster. ~ Greg LeMond. Created by: Kristen Dillon Training Type - High Intensity Working HR Zones - Zone 4 - 5c Total Class Length - 45 minutes of warm up and work efforts. The purpose of this class is threefold: 1. Push your intensity threshold - allow your body to perform beyond what your mind thinks is possible to attain 2. Push your anaerobic threshold - improve fitness with high end training 3. Push your endurance threshold - work at maintaining a very uncomfortable perceived exertion for longer periods of time. As the instructor, this is the most important part of your job - cueing this intensity and using words to help the students know how to maintain it. I live and teach on a small island off the coast of South Carolina, we have VERY flat roads. As a result, many outdoor cyclists who live here spend much of their training time on speed building. It is important to note that both the outdoor road cyclist and indoor cycling enthusiast can benefit from this workout. To improve speed, riders should work at their anaerobic threshold. Both experienced and new riders can use this ride to improve speed at threshold. The intensity of this ride will range from Zone 2 during recovery all the way up to Zone 5. If your classes are not used to zone training, then using perceived exertion for effort level will work great. As their coach, let them know that the class will range from effort levels that are fairly light to effort levels that are VERY VERY HARD. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Current Setlist

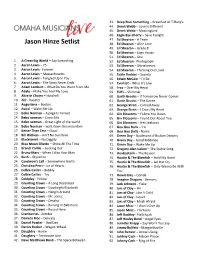

43. Deep Blue Something – Breakfast At Tiffany’s 44. Derek Webb – Love Is Different 45. Derek Webb – Mockingbird 46. Eagle Eye Cherry – Save Tonight 47. Ed Sheeran – A Team Jason Hinze Setlist 48. Ed Sheeran – Afire Love 49. Ed Sheeran – Grade 8 50. Ed Sheeran – Lego House 51. Ed Sheeran – One 1. A Great Big World – Say Something 52. Ed Sheeran - Photograph 2. Aaron Lewis – 75 53. Ed Sheeran – Shirtslieeves 3. Aaron Lewis - Forever 54. Ed Sheeran – Thinking Out Loud 4. Aaron Lewis – Massachusetts 55. Eddie Vedder – Society 5. Aaron Lewis – Tangled Up In You 56. Edwin McCain – I’ll Be 6. Aaron Lewis – The Story Never Ends 57. Everlast – What It’s Like 7. Adam Lambert – What Do You Want From Me 58. Fray – Over My Head 8. Adele – Make You Feel My Love 59. FUEL – Shimmer 9. Alice In Chains – Nutshell 60. Garth Brooks – If Tomorrow Never Comes 10. AIC - Rooster 61. Garth Brooks – The Dance 11. Augustana – Boston 62. George Strait – Carried Away 12. Avicci – Wake Me Up 63. George Strait – I Cross My Heart 13. Bebo Norman – A page Is Turned 64. Gin Blossoms – Follow You Down 14. Bebo norman – Cover Me 65. Gin Blossoms – Found Out About You 15. Bebo norman – Great Light of the world 66. Gin Blossoms – Hey Jealousy 16. Bebo Norman – walk down this mountain 67. Goo Goo Dolls – Iris 17. Better Than Ezra – Good 68. Goo Goo Dolls - Name 18. Bill Withers – Ain’t No Sunshine 69. Green Day – Boulevard of Broken Dreams 19. Blackstreet – No Diggity 70. Green Day – Good Riddance 20. -

ASCAP to Honor New Edition at 21St Annual Rhythm & Soul Music

Source: ASCAP May 29, 2008 08:00 ET ASCAP to Honor New Edition at 21st Annual Rhythm & Soul Music Awards on June 23 in Los Angeles NEW YORK, NY--(Marketwire - May 29, 2008) - The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) will honor New Edition at its 21st Annual Rhythm & Soul Music Awards on June 23, 2008 in Los Angeles, CA. The six members of New Edition will be presented with the prestigious ASCAP Golden Note Award, which is given to songwriters, composers, and artists who have achieved extraordinary career milestones. The invitation-only gala will also honor ASCAP's top songwriters and publishers of 2007. Previous ASCAP Golden Note Award honorees include Lionel Richie, Tom Petty, Stevie Wonder, Jermaine Dupri, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Jay-Z, Quincy Jones, LL Cool J and Steve Miller. Celebrating their 25th anniversary as a group, Ricky Bell, Michael Bivins, Bobby Brown, Ralph Tresvant, Ronnie DeVoe and Johnny Gill established much of the groundwork for the style of music known as new jack swing. In the early 1980s, New Edition sold more units in the United States than any other teen singing group and their success led to the creation of late-80s and 90s boy bands, such as New Kids on the Block, Boyz II Men, the Backstreet Boys and 'N Sync. They have released seven studio albums -- "Candy Girl," "New Edition," "All For Love," "Under the Blue Moon," "Heart Break," "Home Again" and "One Love" -- that spawned several hits, including "Candy Girl," "Popcorn Love," "Cool It Now," "Mr. Telephone Man," "Count Me Out," "A Little Bit of Love (Is All It Takes)," "Earth Angel," "Can You Stand the Rain," "If It Isn't Love," "You're Not My Kind of Girl," "Crucial" and "Hit Me Off." Individually, they have enjoyed successful solo careers and side group projects.