The Cranberry Scare of 1959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arthur B. Langlie Papers Inventory Accession No: 0061-001

UNIVERSITY UBRARIES w UN VERS ITY of WASHI NGTO N Spe ial Colle tions Arthur B. Langlie papers Inventory Accession No: 0061-001 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Guide to the Arthur B. Langlie Papers. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/LanglieArthurB0061_1327/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search Arthur B. Langlie Papers – Inventory and Name Index 0061-001 Part I c..n,;1.,e...,i,,J, 1 J ~v t~_,,~r) J;J!TDl3X '3?0 Tl:-li llIJriWTOO:¥ - ARTHUR B. L.Ai\JGLIE PT• l page number Artifffi.cts 21 Campaign Materials 22 Clippings 20 Columbia Valley Administration 31-39 Correspondence-Incoming 3-12 Correspondence-Outgoing 13 Electrical Power 40-52 Ephemera 20 General Correspondence 13 Lists of Names 20 (Name index to Langlie paperscl-20~) Miscellany 20 Notes on Arrangement I Photographs 20 Reports 16-20 Republican Party 26 Speeches & Writings 14-15 Tape Recorddlngs 20 U.S. F'ederal Civil Defense Administration 27 U. S. President's Committee for the Development of Scientists and Engineers 28 Washington. Forest Advisory Committee 29 ~Thitworth College 30 Part r 3 CORRESPONDENCE: nrcoMING Note: This series was separated from the general correspondence tha.t Langlie had stapled together to allow name-inve:1torying and to simplif;'/ use of the collection. -

SUMMER 12 AR.Indd

Summer 2012 Tekes in Politics 2012 Award Winners Animal House vs. Total Frat Move VOLUME 105 • NUMBER 3 SUMMER 2012 what’s inside THE TEKE is the offi cial publication of Tau Kappa Epsilon International Fraternity. TKE was founded on January 10, 1899, at Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL. departments THE TEKE STAFF Chief Executive Offi cer Shawn A. Babine (Lambda-Delta) Chief Administrative Offi cer John W. Deckard (Grand Chapter) Chief Financial & Risk Offi cer Thomas L. Carter (Grand Chapter) VP, Director of Operations, IT, & Infrasructure Louis L. LeBlanc, CAE (Gamma-Theta) VP of Marketing & Corporate Sponsorships Chris Walsh (Rho-Upsilon) Director of Communication & Public Relations Tom McAninch (Alpha-Zeta) Production Manager Katie Sayre THE TEKE (ISSN 1527-1331) is an educational journal published quarterly in spring, summer, 1915 fall and winter by Tau Kappa Epsilon (a fraternal society),7439 Woodland Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46278-1765. Periodicals Class postage paid at 4 CEO Message Indianapolis, IN, and additional mailing offi ces. TKE Men Do Not Just Vote; They Run for Offi ce! POSTMASTER: send address changes to THE TEKE, 7439 Woodland Drive, Indianapolis, IN 14 Teke on the Street 46278-1765. Political topics, favorites & motivations All alumni Fraters who donate $10 or more to the TKE Educational Foundation, Inc. will receive a 15 Chapter News one-year subscription to THE TEKE. It’s our way of saying thank you and of keeping you informed Chapter Activities, Accomplishments, and 2012 Awards Winners regarding what’s going on in your Fraternity today. 30 Volunteers Greek Life Administrator of the Quarter and Volunteers of the Month for July, LIFETIME GIVING LEVELS Golden Eagle Society - $1,000,000 or more August, and September Knights of a Lasting Legacy - $500,000 - $999,999 Society of 1899 - $250,000 - $499,999 Grand Prytanis Circle - $100,000 - $249,000 on the cover Presidents Circle - $50,000 - $99,999 Leaders Society - $25,000 - $49,999 Scholars Society - $10,000 - $24,999 TKE revisits the ’80s with this retro style magazine. -

Aaron Ihde's Contributions to the History of Chemistry

24 Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 26, Number 1 (2001) AARON IHDE’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY William B. Jensen, University of Cincinnati Aaron Ihde’s career at the University of Wisconsin spanned more than 60 years — first as a student, then as a faculty member, and, finally, as professor emeri- tus. The intellectual fruits of those six decades can be found in his collected papers, which occupy seven bound volumes in the stacks of the Memorial Library in Madison, Wisconsin. His complete bibliography lists more than 342 items, inclusive of the posthumous pa- per printed in this issue of the Bulletin. Of these, roughly 35 are actually the publications of his students and postdoctoral fellows; 64 deal with chemical research, education, and departmental matters, and 92 are book reviews. Roughly another 19 involve multiple editions of his books, reprintings of various papers, letters to newspaper editors, etc. The remaining 132 items rep- resent his legacy to the history of the chemistry com- munity and appear in the attached bibliography (1). Textbooks There is little doubt that Aaron’s textbooks represent his most important contribution to the history of chem- Aaron Ihde, 1968 istry (2). The best known of these are, of course, his The Development of Modern Chemistry, first published Dalton. This latter material was used in the form of by Harper and Row in 1964 and still available as a qual- photocopied handouts as the text for the first semester ity Dover paperback, and his volume of Selected Read- of his introductory history of chemistry course and was, ings in the History of Chemistry, culled from the pages in fact, the manuscript for a projected book designed to of the Journal of Chemical Education and coedited by supplement The Development of Modern Chemistry, the journal’s editor, William Kieffer. -

How Chemists Pushed for Consumer Protection:The Food and Drugs Act

How Chemists Pushed for Consumer Protection: The Food and Drugs Act of 1906 * Originally published in Chemical Heritage 24, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 6-11. By John P. Swann, Ph.D. Introduction The Food and Drugs Act of 1906 brought about a radical shift in the way Americans regarded some of the most fundamental commodities of life itself, like the foods we eat and the drugs we take to restore our health. Today we take the quality and veracity of these products for granted and justifiably complain if they have been compromised. Our expectations have been elevated over the past century by revisions in law and regulation; by shifts—sometimes of a tectonic nature—in the science and technology that apply to our food, drugs, and other consumer products; and by the individuals, organizations, commercial institutions, and media that drive, monitor, commend, and criticize the regulatory systems in place. But to appreciate how America first embraced the regulation of basic consumer products on a national scale, one needs to start with some of the most important people behind the effort—chemists. The USDA Bureau of Chemistry Chemistry helped us understand the foods we ate and the drugs we took even before 1906. In August 1862 Commissioner of Agriculture Isaac Newton appointed Charles M. Wetherill to undertake the duties of Department of Agriculture chemist, just three months after the creation of the department itself. Those duties began with inquiries into grape varieties for sugar content and other qualities. The commercial rationale behind this investigation was made clear in Wetherill’s first report in January 1863: “From small beginnings the culture of the wine grape has become a source of great national wealth, with abundant promise for the future.” But another important role of chemistry was in discerning fakery in the drug supply and in foods. -

Robert F. Goldsworthy an Oral History

Robert F. Goldsworthy An Oral History Interviewed by Sharon Boswell Washington State Oral History Program Office of the Secretary of State Ralph Munro, Secretary of State CONTENTS Dedication Forewords Daniel J. Evans Glenn Terrell Preface Acknowledgment Introduction Biography 1. Farm and Family ...................................................... 1 2. College and Flight School...................................... 18 3. Military Service and POW Experience.............. 26 4. Entering the Legislature........................................ 49 5. Legislative Work, 1957-1965................................ 62 6. The Budget Process ................................................ 80 7. Legislative Work, 1965-1972................................ 94 Appendices A. Our Last Mission B. Our 1997 Trip to Japan C. Meeting with Chieko Kobayashi D. Meritorious Conduct Citation E. WSU Alumni Award F. Caterpillar Club Award G. Military Career Photographs H. Family Photographs I. Legislative Career J. Chronology Index To my wife, Jean, and to my son, Robert, and my daughter, Jill. Jean shared the anxieties and uncertainties of two wars. All three shared the elation of political victory and the many days of separation which followed. Those in politics will understand. Through it all, my family kept their loyalty and sense of humor. FOREWORD BOB GOLDSWORTHY Bob Goldsworthy and I were both elected to the Legislature for the first time in 1956. We were among the first members of what would become, in a few years, a whole new generation of Republican legislators and officeholders. Bob was always a friend to everyone. With his long experience in farming and in the Air Force, he wielded substantial influence in agricultural and military affairs. He was most influential, however, when he became chairman of the House Appropriations Committee in 1967. By then, I was governor and I depended on Bob’s leadership to produce a good budget; one that would adequately finance education, better transportation facilities, and the preservation of the environment. -

Food Standards and the Peanut Butter & Jelly Sandwich

Food Standards and the Peanut Butter & Jelly Sandwich From: Food, Science, Policy, and Regulation in the Twentieth Century: International and Comparative Perspectives, David F. Smith and Jim Phillips, eds. (London and New York: Routledge, 2000) pp. 167-188. By Suzanne White Junod Britain’s 1875 and 1899 Sale of Food and Drugs Acts were similar in intent to the 1906 US Pure Food and Drugs Act, as Michael French and Jim Phillips have shown. Both statutes defined food adulterations as a danger to health and as consumer fraud. In Britain, the laws were interpreted and enforced by the Local Government Board and then, from its establishment in 1919, by the Ministry of Health. Issues of health rather than economics, therefore, dominated Britain’s regulatory focus. The US Congress, in contrast, rather than assigning enforcement of the 1906 Act to the Public Health Service, or to the Department of Commerce, as some had advocated, charged an originally obscure scientific bureau in the Department of Agriculture with enforcement of its 1906 statute. In the heyday of analytical chemistry, and in the midst of the bacteriological revolution, Congress transformed the Bureau of Chemistry into a regulatory agency, fully expecting that science would be the arbiter of both health and commercial issues. Led by ‘crusading chemist’ Harvey Washington Wiley, the predecessor of the modern Food and Drug Administration initiated food regulatory policies that were more interventionist from their inception. [1] Debates about the effects of federal regulation on the US economy have been fierce, with economists and historians on both sides of the issue generating a rich literature. -

Cause of Chehalis Fire Still Unknown AID: American Red While Authorities Have Al- Tors Can Enter

More Than 2,000 Civil War Coming Re-Enactors Meet for Event to Chehalis / Main 5 $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com July 18, 2013 Cause of Chehalis Fire Still Unknown AID: American Red While authorities have al- tors can enter. ready started the investigation, it The fire destroyed the apart- Cross Assisting Those could be a few days before crews ment complex, a two-story build- Displaced by Blaze That can enter the building to contin- ing on the corner of Northwest ue it, said Riverside Fire Author- Rhode Island Place and North- Destroyed Apartment ity Chief Jim Walkowski, who is west West Street, located a block Building, House also the acting chief of the Che- from the train tracks in down- halis Fire Department. town Chehalis, and severely dam- By Stephanie Schendel The chief said there are sev- aged the house to the west of the [email protected] eral rumors about what could apartments. The roofs of both have caused the blaze, but he de- buildings partially collapsed. Fire investigators are still clined to speculate. please see FIRE, page Main 14 looking into the cause of the He said officials are waiting fire that destroyed an apartment for an engineer to examine the Pete Caster / [email protected] building as well as the adjacent remains of the complex and de- Damage from a dual structure ire on one-and-a-half story house early termine what needs to be done NW West Street is seen on Tuesday af- Tuesday morning. -

Notes for Tour of Townsend Mansion, Home of the Cosmos

NOTES FOR TOUR OF TOWNSEND MANSION HOME OF THE COSMOS CLUB July 2015 Harvey Alter (CC: 1970) Editor Updated: Jean Taylor Federico (CC: 1992), Betty C. Monkman (CC: 2004), FOREWORD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These notes are for docent training, both background and possible speaking text for a walking tour of the Club. The material is largely taken from notes prepared by Bill Hall (CC: 1995) in 2000, Ed Bowles (CC: 1973) in 2004, and Judy Holoviak (CC: 1999) in 2004 to whom grateful credit is given. Many of the details are from Wilcomb Washburn’s centennial history of the Club. The material on Jules Allard is from the research of Paul Miller, curator of the Newport Preservation Society. The material was assembled by Jack Mansfield (CC: 1998), to whom thanks are given. Members Jean Taylor Federico and Betty Monkman with curatorial assistant, Peggy Newman updated the tour and added references to notable objects and paintings in the Cosmos Club collection in August, 2009. This material was revised in 2010 and 2013 to note location changes. Assistance has been provided by our Associate Curators: Leslie Jones, Maggie Dimmock, and Yve Colby. Acknowledgement is made of the comprehensive report on the historic structures of the Townsend Mansion by Denys Peter Myers (CC: 1977), 1990 rev. 1993. The notes are divided into two parts. The first is an overview of the Club’s history. The second part is tour background. The portion in bold is recommended as speaking notes for tour guides followed by information that will be useful for elaboration and answering questions. The notes are organized by floor, room and section of the Club, not necessarily in the order tours may take. -

Judicial Sanctions and Legislative Redistricting in Washington State

Washington Law Review Volume 45 Number 4 6-1-1970 Judicial Sanctions and Legislative Redistricting in Washington State W. Basil McDermott Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation W. B. McDermott, Judicial Sanctions and Legislative Redistricting in Washington State, 45 Wash. L. Rev. 681 (1970). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol45/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON LAW REVIEW Volume 45, Number 4, 1970 JUDICIAL SANCTIONS AND LEGISLATIVE REDISTRICTING IN WASHINGTON STATE W. Basil McDermott* INTRODUCTION History has been unkind to state legislatures. As one looks at the development of those bodies in our society today, only the dull are even mildly optimistic about the ability of such assemblies to under- stand, let alone manage, the immensely disruptive changes that have been taking place in this century. Change is history's joker slipped openly into a deck of stacked problems that frustrate the most able politicians and bewilder the vast majority. Like generals who are best prepared to fight yesterday's war, state legislatures look boldly toward the past hoping against hope that the times will stop a-changing. Wise men will make no bets. In a sense the story is an old one-the problems facing men out- grew the capacity of the political structures designed to handle such problems. -

Harvey Wiley, the Man Who Changed America One Bite at a Time Rishit Shaquib Junior Division Individual Documentary Process Pape

Harvey Wiley, The Man Who Changed America One Bite at A Time Rishit Shaquib Junior Division Individual Documentary Process Paper: 500 Words When we first received the topic breakthroughs in history, I immediately thought of people we often heard about such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Albert Einstein, and although these are famous pioneers in science and social change, I didn’t want to tell a well-known story. One day while researching I came across the story of a man who poisoned a group of applicants in order to pass some of America’s first food and drug bills. I began to research further into the topic and came across a man by the name of Harvey Wiley. His story intrigued me and the more I researched the more interesting the story became. I soon found that this story was the perfect one for me to tell. In order to conduct my research, I developed a timeline which also assisted in how I developed my documentary. By outlining important people and significant events, I could effectively organize my research. I used a variety of sources, spending time in local and online libraries looking for encyclopedias and books as well as scouring the web for valuable sources of information. I was cautious in citing websites as they are vulnerable to bias, and glorification which I didn’t want influencing my documentary. Archives played a valuable role throughout my research, often providing other sources to research and a great source of primary sources. I reached out and utilized a multitude of archives, such as those from Harvard, and from The Library of Congress where I found many documents from his work. -

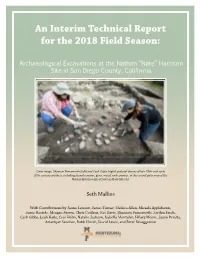

An Interim Technical Report for the 2018 Field Season

An Interim Technical Report for the 2018 Field Season: Archaeological Excavations at the Nathan “Nate” Harrison Site in San Diego County, California Cover image. Shannon Farnsworth (left) and Caeli Gibbs (right) pedestal dozens of late 19th- and early 20th-century artifacts, including faunal remains, glass, metal, and ceramics, in the central patio area of the Nathan Harrison site (Courtesy Robb Hirsch). Seth Mallios With Contributions by Jaime Lennox, James Turner, Melissa Allen, Micaela Applebaum, Jamie Bastide, Meagan Brown, Chris Coulson, Kat Davis, Shannon Farnsworth, Jordan Finch, Caeli Gibbs, Leah Hails, Cece Holm, Natalie Jackson, Isabella Montalvo, Hilary Moore, Jason Peralta, Amethyst Sanchez, Robb Hirsch, David Lewis, and Peter Brueggeman Published by Montezuma Publishing Aztec Shops Ltd. San Diego State University San Diego, California 92182-1701 619-594-7552 www.montezumapublishing.com Copyright © 2018 All Rights Reserved. ISBN: 978-0-7442-3708-5 Copyright © 2018 by Montezuma Publishing and the author(s), Seth Mallios et al. The compilation, formatting, printing and binding of this work is the exclusive copyright of Montezuma Publishing and the author(s), Seth Mallios et al. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including digital, except as may be expressly permitted by the applicable copyright statutes or with written permission of the Publisher or Author(s). Publishing Manager: Kim Mazyck Design and Formatting: Lia Dearborn Cover Design: Lia Dearborn Quality Control: Joshua Segui THE NATHAN “NATE” HARRISON HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT iv AN INTERIM TECHNICAL REPORT FOR THE 2018 FIELD SEASON Abstract San Diego State University (SDSU) Department of Anthropology Professor Seth Mallios directed scientific archaeological excavations at the Nathan “Nate” Harrison site in San Diego County for a seventh field season in 2018. -

Gender, Environment, and the Rise of Nutritional Science

THESIS “LEARNING WHAT TO EAT”: GENDER, ENVIRONMENT, AND THE RISE OF NUTRITIONAL SCIENCE IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICA Submitted by Kayla Steele Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Mark Fiege Co-Advisor: Ruth Alexander Adrian Howkins Sue Doe ABSTRACT “LEARNING WHAT TO EAT”: GENDER, ENVIRONMENT, AND THE RISE OF NUTRITIONAL SCIENCE IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICA This thesis examines the development of nutritional science from the 1910s to 1940s in the United States. Scientists, home economists, dieticians, nurses, advertisers, and magazine columnists in this period taught Americans to value food primarily for its nutritional components—primarily the quantity of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals in every item of food—instead of other qualities such as taste or personal preference. I argue that most food experts believed nutritional science could help them modernize society by teaching Americans to choose the most economically efficient foods that could optimize the human body for perfect health and labor; this goal formed the ideology of nutrition, or nutritionism, which dominated education campaigns in the early twentieth century. Nutrition advocates believed that food preserved a vital connection between Americans and the natural world, and their simplified version of nutritional science could modernize the connection by making it more rational and efficient. However, advocates’ efforts also instilled a number of problematic tensions in the ways Americans came to view their food, as the relentless focus on invisible nutrients encouraged Americans to look for artificial sources of nutrients such as vitamin pills and stripped Americans of the ability to evaluate food themselves and forced them to rely on scientific expertise for guidance.