The Next Point Annual 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

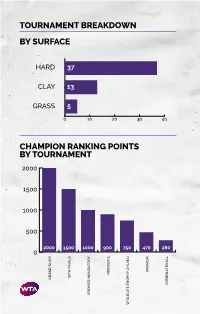

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

Additional Players to Watch Players to Watch

USTA PRO CIRCUIT PLAYER INFORMATION PLAYERS TO WATCH Prakash Amritraj (IND) pg. 2 Kevin Kim pg. 6 Kevin Anderson (RSA) Evan King Carsten Ball (AUS) Austin Krajicek Brian Battistone Alex Kuznetsov Dann Battistone Jesse Levine Alex Bogomolov Jr. pg. 3 Michael McClune pg. 7 Devin Britton Nicholas Monroe Chase Buchanan Wayne Odesnik Lester Cook Rajeev Ram Ryler DeHeart Bobby Reynolds Amer Delic pg. 4 Michael Russell pg. 8 Taylor Dent Tim Smyczek Somdev Devvarman (IND) Vince Spadea Alexander Domijan Blake Strode Brendan Evans Ryan Sweeting Jan-Michael Gambill pg. 5 Bernard Tomic (AUS) pg. 9 Robby Ginepri Michael Venus Ryan Harrison Jesse Witten Scoville Jenkins Michael Yani Robert Kendrick Donald Young ADDITIONAL PLAYERS TO WATCH Jean-Yves Aubone pg. 10 Nick Lindahl (AUS) pg. 12 Sekou Bangoura Eric Nunez Stephen Bass Greg Ouellette Yuki Bhambri (IND) Nathan Pasha Alex Clayton Todd Paul Jordan Cox Conor Pollock Benedikt Dorsch (GER) Robbye Poole Adam El Mihdawy Tennys Sandgren Mitchell Frank Raymond Sarmiento Bjorn Fratangelo Nate Schnugg Marcus Fugate pg. 11 Holden Seguso pg. 13 Chris Guccione (AUS) Phillip Simmonds Jarmere Jenkins John-Patrick Smith Steve Johnson Jack Sock Roy Kalmanovich Ryan Thacher Bradley Klahn Nathan Thompson Justin Kronauge Ty Trombetta Nikita Kryvonos Kaes Van’t Hof Denis Kudla Todd Widom Harel Levy (ISR) Dennis Zivkovic ** All players American unless otherwise noted. * All information as of February 1, 2010 P L A Y E R S T O W A T C H Prakash Amritraj (IND) Age: 26 (10/2/83) Hometown: Encino, Calif. 2009 year-end ranking: 215 Amritraj represents India in Davis Cup but has strong ties—with strong results—in the United States. -

How the Court Surface Is Affecting the Serve-And-Volley Tristan Barnett

How the court surface is affecting the serve-and-volley Tristan Barnett Strategic Games www.strategicgames.com.au 1. Introduction The modern version of the game (official name of Lawn Tennis) as we recognize it today was designed and patented by Major Walter Clopton Wingfield in 1873. Two years later in 1875, the official rules of the game were drawn up by Marylebone Cricket Club, and two years later in 1877, Wimbledon began on a grass surface as the first official championships. All four grand slam events have been played on a grass surface. Wimbledon is the only grand slam event played on a grass court today and has always been played on a grass court surface. The French Open began in 1891 on a grass surface and remained on grass until 1928 when the surface was changed to clay. The US Open began in 1881 on a grass surface; until it was changed to clay from 1975-1977 and from 1978 has been played on a hard court surface. Finally, the Australian Open began in 1905 on a grass surface and remained on grass until 1988 when the surface was changed to a hard court. There has been a change in the proportion of tournaments played on different court surfaces from 1877 to 2010. Firstly, for the first 14 years of the game, all tournaments (grand slam and non grand slam) were played on grass. Secondly, for the first 101 years of the game all tournaments were played on the natural surfaces of grass and clay. Thirdly, according to the ITF, until the early 1970’s, the majority of tournaments were played on grass including three out of the four grand slams. -

PR Move to Attract More Capital and Investment

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Djokovic wins US Open, equals QSE off ers German Sampras’ fi rms new promising opportunities mark published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 10938 September 11, 2018 Moharram 1, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Qatar, US review ties PR move to Our Say attract more capital and By Faisal Abdulhameed al-Mudahka Editor-in-Chief investment O Cardholders will enjoy health, The root of His Highness the Deputy Amir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani met at his off ice at the Amiri Diwan yesterday with the President of US Chamber of Commerce Thomas Donohue and US businessmen delegation, who called on the Deputy Amir education benefits to greet him on their visit to the country. During the meeting, they reviewed the strong relations between Qatar and the US terrorism and discussed ways to boost and develop them in various fields especially economic partnership and trade exchange, in he initiative to grant permanent and investment purposes in accord- light of the Qatar-US Business Council. They also exchanged views on future joint projects which will benefit both countries residency to non-Qatari indi- ance with stipulations. and their people. Tviduals will help increase invest- The cardholder may leave the coun- still exists ments and attract more capital, con- try and return to it during the period of tributing to further economic growth its validity without obtaining any con- In a a series of co-ordinated at- in the country, while the State can also sent or permit. -

DI-P15-15-1-(P)- Tas.Qxd

Saturday 15th January, 2010 15 Australian Open men’s capsules BY DENNIS PASSA MELBOURNE, Australia (AP) - Men to watch at the Australian Open, which begins Monday (rankings in parenthe- ses): ANDY MURRAY (5) Age: 23 Country: Britain 2010 Singles Titles: 2 Career Singles Titles: 16 Major Titles: 0 Last 5 Australian Opens: ‘10-F, ‘09-4th, ‘08-1st, ‘07-4th, RAFAEL NADAL (1) ‘06-1st, ‘05-DNP. Topspin: Murray is 0-2 in Grand Slam finals - both loss- es to Roger Federer, at the 2008 U.S. Open and 2010 Australian RAFAEL NADAL (1) Open - and he’s trying to become the first British man to win Age: 24 last year’s French Open, Wimbledon a major championship since Fred Perry in 1936. The pressure Country: Spain and U.S. Open. That would take his of that task showed when he made a tearful speech after last 2010 Match Record: 71-10 Grand Slam total to 10. The Spaniard is year’s loss at Rod Laver Arena. Played with British team- 2010 Singles Titles: 7 aiming to be the first man since Rod mate Laura Robson at the Hopman Cup two weeks ago, and Career Singles Titles: 43 Laver to hold all four Grand Slam tro- the Kooyong exhibition this week to try to hone his game Major Titles: 9 - Wimbledon (‘08, phies at once, although it won’t be a ahead of Melbourne Park. ‘10), Australian Open (‘09), true Grand Slam - Laver won all four in French Open (‘05, ‘06, ‘07, ‘08, ‘10), a calendar year in 1969. Got 2011 off to U.S. -

Match Notes 0-0 5-1 0-0

MATCH NOTES ROLAND GARROS PARIS, FRANCE MAY 30 - JUNE 12, 2021 | €34,367,216 DAY 8 MATCH-UPS SERENA ELENA 7 WILLIAMS 0-0 RYBAKINA 21 HEAD-TO-HEAD RECORD Williams is contesting the round of 16 at a Slam for the 64th time in her career, while Rybakina is doing so for the very first... Rybakina is one of four players in the draw yet to drop a set... Williams reached the fourth round on her Roland Garros debut in 1998, one year before Rybakina was born VICTORIA ANASTASIA 15 AZARENKA 5-1 PAVLYUCHENKOVA 31 HEAD-TO-HEAD RECORD Azarenka won their most recent encounter at 2019 Monterrey in straight sets... Pavlyuchenkova knocked out the highest-ranked player left in the draw, Sabalenka, in the previous round... Azarenka last reached the fourth round here in 2013... Pavlyuchenkova made QF in Paris a decade ago MARKETA PAULA 33 20 VONDROUSOVA 0-0 BADOSA HEAD-TO-HEAD RECORD Badosa beat Vondrousova en route to the Roland Garros girls’ singles title in 2015... Vondrousova went on to reach the women’s final four years later...Badosa has won more clay court matches in 2021 than any other woman... Vondrousova entered the tournament with just one win on clay all year TAMARA SORANA ZIDANSEK 0-0 CIRSTEA HEAD-TO-HEAD RECORD Cirstea is one of three thirtysomethings left in the draw... Prior to this fortnight, Zidansek had never been beyond the second round at a Slam... Cirstea appeared in QF here back in 2009... Zidansek is bidding the become the first woman representing Slovenia to reach the last eight at a major MATCH NOTES ROLAND GARROS PARIS, FRANCE MAY -

2020 Women’S Tennis Association Media Guide

2020 Women’s Tennis Association Media Guide © Copyright WTA 2020 All Rights Reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying- without the written permission of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Compiled by the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Communications Department WTA CEO: Steve Simon Editor-in-Chief: Kevin Fischer Assistant Editors: Chase Altieri, Amy Binder, Jessica Culbreath, Ellie Emerson, Katie Gardner, Estelle LaPorte, Adam Lincoln, Alex Prior, Teyva Sammet, Catherine Sneddon, Bryan Shapiro, Chris Whitmore, Yanyan Xu Cover Design: Henrique Ruiz, Tim Smith, Michael Taylor, Allison Biggs Graphic Design: Provations Group, Nicholasville, KY, USA Contributors: Mike Anders, Danny Champagne, Evan Charles, Crystal Christian, Grace Dowling, Sophia Eden, Ellie Emerson,Kelly Frey, Anne Hartman, Jill Hausler, Pete Holtermann, Ashley Keber, Peachy Kellmeyer, Christopher Kronk, Courtney McBride, Courtney Nguyen, Joan Pennello, Neil Robinson, Kathleen Stroia Photography: Getty Images (AFP, Bongarts), Action Images, GEPA Pictures, Ron Angle, Michael Baz, Matt May, Pascal Ratthe, Art Seitz, Chris Smith, Red Photographic, adidas, WTA WTA Corporate Headquarters 100 Second Avenue South Suite 1100-S St. Petersburg, FL 33701 +1.727.895.5000 2 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Women’s Tennis Association Story . 4-5 WTA Organizational Structure . 6 Steve Simon - WTA CEO & Chairman . 7 WTA Executive Team & Senior Management . 8 WTA Media Information . 9 WTA Personnel . 10-11 WTA Player Development . 12-13 WTA Coach Initiatives . 14 CALENDAR & TOURNAMENTS 2020 WTA Calendar . 16-17 WTA Premier Mandatory Profiles . 18 WTA Premier 5 Profiles . 19 WTA Finals & WTA Elite Trophy . 20 WTA Premier Events . 22-23 WTA International Events . -

Yearbook Yearbook

2010 USTA NORTHERN YEARBOOK Cindy Lim – Girls 12-13 Rapid Rally 4.5 Adult Men’s USTA League Tennis National Champions National Champion Ellie Kantar Brandon Tennis Association Arthur Ashe Essay Contest USTA CTA of the Year National Winner Baseline Tennis Center USTA Organization Member of the Year Elizabeth Walsh www.northern.usta.com Elliott Sprecher Arthur Ashe Essay Contest Nike National 14s Masters Series National Winner Champion 2 2010 USTA Northern Yearbook 2010 YEARBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Director Statement/Mission Statement....................................4 President’s Message.................................................................................................5 Councils and Committees........................................................................................5 Board of Directors/Executive Committee....................................................6 USTA Northern Staff.................................................................................................7 USTA Northern Organizational Structure.......................................................8 USTA Northern Diversity Statement.................................................................9 Sponsor Appreciation.............................................................................................11 2009 Organizational Members.......................................................................12 2009 Award Winners............................................................................................14 2009 USTA -

ADCTF Annual Report 2018

THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP 2018 TENNIS FOUNDATION ANNUAL ABN 90 004 905 060 Approved by Tennis Australia REPORT THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION Annual Report 2018 1 THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION Annual Report 2018 2 THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION ABN 90 004 905 060 NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Notice is hereby given that the forty-seventh Annual General Meeting of The Australian Davis Cup Tennis Foundation will be held in the Clubhouse of the Royal South Yarra Lawn Tennis Club, Williams Road North, Toorak, on Tuesday 27th November 2018 at 8.00pm. BUSINESS 1. To receive, consider and if thought fit, to adopt the Directors' Report, the Directors' Declaration, the Statement of Financial Position as at 30th June 2018, the Statement of Comprehensive Income, the Statement of Cash Flows and the Statement of Changes in Equity for the year ended 30th June 2018 together with the Auditor's Report thereon. 2. To elect four (4) Directors to replace those persons retiring in accordance with the Constitution. 3. To transact any other business that, being lawfully brought forward, is accepted by the Chairman for discussion. BY ORDER OF THE BOARD Alan J Cobb. Honorary Secretary. Melbourne, 1st October, 2018 THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION Annual Report 2018 1 PROXIES A Member entitled to attend and vote at the Meeting is entitled to appoint one proxy to attend and vote in his or her stead. A proxy must be a Member. The form for the appointment of a proxy is available on application to the Honorary Secretary and must be lodged with the Honorary Secretary no later than 48 hours prior to the scheduled commencement of the Meeting. -

Game, Set, Watched: Governance, Social Control and Surveillance in Professional Tennis

GAME, SET, WATCHED: GOVERNANCE, SOCIAL CONTROL AND SURVEILLANCE IN PROFESSIONAL TENNIS By Marie-Pier Guay A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November, 2013 Copyright © Marie-Pier Guay, 2013 Abstract Contrary to many major sporting leagues such as the NHL, NFL, NBA, and MLB, or the Olympic Games as a whole, the professional tennis industry has not been individually scrutinized in terms of governance, social control, and surveillance practices. This thesis presents an in-depth account of the major governing bodies of the professional tennis circuit with the aim of examining how they govern, control, constrain, and practice surveillance on tennis athletes and their bodies. Foucault’s major theoretical concepts of disciplinary power, governmentality, and bio-power are found relevant today and can be enhanced by Rose’s ethico-politics model and Haggerty and Ericson’s surveillant assemblage. However, it is also shown how Foucault, Rose, and Haggerty and Ericson’s different accounts of “modes of governing” perpetuate sociological predicaments of professional tennis players within late capitalism. These modes of surveillance are founded on a meritocracy based on the ATP and WTA rankings systems. A player’s ranking affects how he or she is governed, surveilled, controlled, and even punished. Despite ostensibly promoting tennis athletes’ health protection and wellbeing, the systems of surveillance, governance, and control rely on a biased and capitalistically-driven meritocracy that actually jeopardizes athletes’ health and contributes to social class divisions, socio- economic inequalities, gender discrimination, and media pressure. -

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest for Perfection

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER New Chapter Press Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic Originally published in Germany under the title “Das Tennis-Genie” by Pendo Verlag. © Pendo Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich and Zurich, 2006 Published across the world in English by New Chapter Press, www.newchapterpressonline.com ISBN 094-2257-391 978-094-2257-397 Printed in the United States of America Contents From The Author . v Prologue: Encounter with a 15-year-old...................ix Introduction: No One Expected Him....................xiv PART I From Kempton Park to Basel . .3 A Boy Discovers Tennis . .8 Homesickness in Ecublens ............................14 The Best of All Juniors . .21 A Newcomer Climbs to the Top ........................30 New Coach, New Ways . 35 Olympic Experiences . 40 No Pain, No Gain . 44 Uproar at the Davis Cup . .49 The Man Who Beat Sampras . 53 The Taxi Driver of Biel . 57 Visit to the Top Ten . .60 Drama in South Africa...............................65 Red Dawn in China .................................70 The Grand Slam Block ...............................74 A Magic Sunday ....................................79 A Cow for the Victor . 86 Reaching for the Stars . .91 Duels in Texas . .95 An Abrupt End ....................................100 The Glittering Crowning . 104 No. 1 . .109 Samson’s Return . 116 New York, New York . .122 Setting Records Around the World.....................125 The Other Australian ...............................130 A True Champion..................................137 Fresh Tracks on Clay . .142 Three Men at the Champions Dinner . 146 An Evening in Flushing Meadows . .150 The Savior of Shanghai..............................155 Chasing Ghosts . .160 A Rivalry Is Born . -

United States Vs. Czech Republic

United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREVIEW NOTES PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES (U.S. AND CZECH REPUBLIC) U.S. FED CUP TEAM RECORDS U.S. FED CUP INDIVIDUAL RECORDS ALL-TIME U.S. FED CUP TIES RELEASES/TRANSCRIPTS 2017 World Group (8 nations) First Round Semifinals Final February 11-12 April 22-23 November 11-12 Czech Republic at Ostrava, Czech Republic Czech Republic, 3-2 Spain at Tampa Bay, Florida USA at Maui, Hawaii USA, 4-0 Germany Champion Nation Belarus at Minsk, Belarus Belarus, 4-1 Netherlands at Minsk, Belarus Switzerland at Geneva, Switzerland Switzerland, 4-1 France United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 For more information, contact: Amanda Korba, (914) 325-3751, [email protected] PREVIEW NOTES The United States will face the Czech Republic in the 2017 Fed Cup by BNP Paribas World Group Semifinal. The best-of-five match series will take place on an outdoor clay court at Saddlebrook Resort in Tampa Bay. The United States is competing in its first Fed Cup Semifinal since 2010. Captain Rinaldi named 2017 Australian Open semifinalist and world No. 24 CoCo Vandeweghe, No. 36 Lauren Davis, No. 49 Shelby Rogers, and world No. 1 doubles player and 2017 Australian Open women’s doubles champion Bethanie Mattek-Sands to the U.S. team. Vandeweghe, Rogers, and Mattek- Sands were all part of the team that swept Germany, 4-0, earlier this year in Maui.