FROM SHAMOON to STONEDRILL Wipers Attacking Saudi Organizations and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semi-Automated Parallel Programming in Heterogeneous Intelligent Reconfigurable Environments (SAPPHIRE) Sean Stanek Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 Semi-automated parallel programming in heterogeneous intelligent reconfigurable environments (SAPPHIRE) Sean Stanek Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Stanek, Sean, "Semi-automated parallel programming in heterogeneous intelligent reconfigurable environments (SAPPHIRE)" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12560. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12560 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Semi-automated parallel programming in heterogeneous intelligent reconfigurable environments (SAPPHIRE) by Sean Stanek A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Computer Science Program of Study Committee: Carl Chang, Major Professor Johnny Wong Wallapak Tavanapong Les Miller Morris Chang Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Sean Stanek, 2012. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................... -

Attacking from Inside

WIPER MALWARE: ATTACKING FROM INSIDE Why some attackers are choosing to get in, delete files, and get out, rather than try to reap financial benefit from their malware. AUTHORED BY VITOR VENTURA WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM MARTIN LEE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY from system impact. Some wipers will destroy systems, but not necessarily the data. On the In a digital era when everything and everyone other hand, there are wipers that will destroy is connected, malicious actors have the perfect data, but will not affect the systems. One cannot space to perform their activities. During the past determine which kind has the biggest impact, few years, organizations have suffered several because those impacts are specific to each kinds of attacks that arrived in many shapes organization and the specific context in which and forms. But none have been more impactful the attack occurs. However, an attacker with the than wiper attacks. Attackers who deploy wiper capability to perform one could perform the other. malware have a singular purpose of destroying or disrupting systems and/or data. The defense against these attacks often falls back to the basics. By having certain Unlike malware that holds data for ransom protections in place — a tested cyber security (ransomware), when a malicious actor decides incident response plan, a risk-based patch to use a wiper in their activities, there is no management program, a tested and cyber direct financial motivation. For businesses, this security-aware business continuity plan, often is the worst kind of attack, since there is and network and user segmentation on top no expectation of data recovery. -

The Middle East Under Malware Attack Dissecting Cyber Weapons

The Middle East under Malware Attack Dissecting Cyber Weapons Sami Zhioua Information and Computer Science Department King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals Dhahran, Saudi Arabia [email protected] Abstract—The Middle East is currently the target of an un- have been designed by the same unknown entity 1. The next precedented campaign of cyber attacks carried out by unknown malware of this lineage was Flame [7] which was discovered parties. The energy industry is praticularly targeted. The in May 2012 by Kaspersky Lab while investigating another attacks are carried out by deploying extremely sophisticated malware. The campaign opened by the Stuxnet malware in piece of malware called Wiper [8]. Flame features very 2010 and then continued through Duqu, Flame, Gauss, and unusual characteristics such as large size, large number of Shamoon malware. This paper is a technical survey of the modules, self adapting, etc. As Duqu, Flame’s objective is attacking vectors utilized by the three most famous malware, data collection and espionnage. Gauss [9] is another data namely, Stuxnet, Flame, and Shamoon. We describe their main stealing malware discovered in June 2012 by Kaspersky Lab modules, their sophisticated spreading capabilities, and we discuss what it sets them apart from typical malware. The focusing on banking information. Flame and Gauss exhibit main purpose of the paper is to point out the recent trends striking similarities and several technical evidences indicate infused by this new breed of malware into cyber attacks. that they come from the same “factories” that produced Stuxnet and Duqu [9]. The latest malware-based attack Keywords-Malwares; Information Security; Targeted At- tacks; Stuxnet; Duqu; Flame; Gauss; Shamoon targeting the middle east was the Shamoon attack on Saudi Aramco [10]. -

A PRACTICAL METHOD of IDENTIFYING CYBERATTACKS February 2018 INDEX

In Collaboration With A PRACTICAL METHOD OF IDENTIFYING CYBERATTACKS February 2018 INDEX TOPICS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 OVERVIEW 5 THE RESPONSES TO A GROWING THREAT 7 DIFFERENT TYPES OF PERPETRATORS 10 THE SCOURGE OF CYBERCRIME 11 THE EVOLUTION OF CYBERWARFARE 12 CYBERACTIVISM: ACTIVE AS EVER 13 THE ATTRIBUTION PROBLEM 14 TRACKING THE ORIGINS OF CYBERATTACKS 17 CONCLUSION 20 APPENDIX: TIMELINE OF CYBERSECURITY 21 INCIDENTS 2 A Practical Method of Identifying Cyberattacks EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW SUMMARY The frequency and scope of cyberattacks Cyberattacks carried out by a range of entities are continue to grow, and yet despite the seriousness a growing threat to the security of governments of the problem, it remains extremely difficult to and their citizens. There are three main sources differentiate between the various sources of an of attacks; activists, criminals and governments, attack. This paper aims to shed light on the main and - based on the evidence - it is sometimes types of cyberattacks and provides examples hard to differentiate them. Indeed, they may of each. In particular, a high level framework sometimes work together when their interests for investigation is presented, aimed at helping are aligned. The increasing frequency and severity analysts in gaining a better understanding of the of the attacks makes it more important than ever origins of threats, the motive of the attacker, the to understand the source. Knowing who planned technical origin of the attack, the information an attack might make it easier to capture the contained in the coding of the malware and culprits or frame an appropriate response. the attacker’s modus operandi. -

Docker Windows Task Scheduler

Docker Windows Task Scheduler Genealogical Scarface glissading, his karyotype outgone inflicts overflowingly. Rudolph is accessorial and suckers languorously as sociologistic Engelbart bridled sonorously and systematises sigmoidally. Which Cecil merchandises so unbelievably that Cole comedowns her suavity? Simple task runner that runs pending tasks in Redis when Docker container. With Docker Content Trust, see will soon. Windows Tip Run applications in extra background using Task. Cronicle is a multi-server task scheduler and runner with a web based front-end UI It handles both scheduled repeating and on-demand jobs targeting any. Django project that you would only fetch of windows task directory and how we may seem. Docker schedulers and docker compose utility program by learning service on a scheduled time, operators and manage your already interact with. You get a byte array elements followed by the target system privileges, manage such data that? Machine learning service Creatio Academy. JSON list containing all my the jobs. As you note have noticed, development, thank deity for this magazine article. Docker-crontab A docker job scheduler aka crontab for. Careful with your terminology. Sometimes you and docker schedulers for task failed job gets silently redirected to get our task. Here you do want to docker swarm, task scheduler or scheduled background tasks in that. Url into this script in one easy to this was already existing cluster created, it retry a little effort. Works pretty stark deviation from your code is followed by searching for a process so how to be executed automatically set. Now docker for windows service container in most amateur players play to pass as. -

Fractional Dynamics of Stuxnet Virus Propagation in Industrial Control Systems

mathematics Article Fractional Dynamics of Stuxnet Virus Propagation in Industrial Control Systems Zaheer Masood 1, Muhammad Asif Zahoor Raja 2,* , Naveed Ishtiaq Chaudhary 2, Khalid Mehmood Cheema 3 and Ahmad H. Milyani 4 1 Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Capital University of Science and Technology, Islamabad 44000, Pakistan; [email protected] 2 Future Technology Research Center, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, 123 University Road, Section 3, Douliou 64002, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 School of Electrical Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The designed fractional order Stuxnet, the virus model, is analyzed to investigate the spread of the virus in the regime of isolated industrial networks environment by bridging the air-gap between the traditional and the critical control network infrastructures. Removable storage devices are commonly used to exploit the vulnerability of individual nodes, as well as the associated networks, by transferring data and viruses in the isolated industrial control system. A mathematical model of an arbitrary order system is constructed and analyzed numerically to depict the control mechanism. A local and global stability analysis of the system is performed on the equilibrium points derived Citation: Masood, Z.; Raja, M.A.Z.; for the value of a = 1. To understand the depth of fractional model behavior, numerical simulations Chaudhary, N.I.; Cheema, K.M.; are carried out for the distinct order of the fractional derivative system, and the results show that Milyani, A.H. -

Enterprise Job Scheduling Checklist

••• ••• ••• 2 Forest Park Drive Farmington, CT 06032 Tel: 800 261 JAMS www.JAMSScheduler.com Enterprise Job Scheduling Checklist Following is a detailed list of evaluation criteria that you can use to benchmark the features and functions of various job schedulers your organization is considering. This checklist provides a way to thoroughly assess how well a given product meets your needs now and in the future. Product X General Cross Platform Scheduling Capabilities (Windows, UNIX, Linux, OpenVMS, System i, All Virtual Platforms, MacOS, zLinux, etc.) Support for native x64 and x86 Windows platforms Single GUI to connect to multiple Schedulers and Agents if necessary Kerberos Support Active Directory Support / ADAM Support Windows Management Instrumentation High Availability Architecture supporting Clustering and Standalone Automated Failover Scalable Architecture to support 500k+ jobs/day and more than 2,500 Server Connections Event-Driven Architecture Free, Unlimited Deployment of Admin Clients Scheduling Date/time based scheduling Event based scheduling Ad hoc scheduling Multiple jobs can be tied together in a Setup or Workflow Nested Jobs and Job Plans supported through Setups and Workflows Unlimited number of Job dependencies on one or multiple jobs in a Setup or Workflow Job dependencies between different schedulers File presence, absence & available dependencies and events Variable comparison dependencies Graphical Gantt view of the schedule with projected time runs Hooks for user defined dependencies Graphical view of job stream -

Windows Intruder Detection Checklist

Windows Intruder Detection Checklist http://www.cert.org/tech_tips/test.html CERT® Coordination Center and AusCERT Windows Intruder Detection Checklist This document is being published jointly by the CERT Coordination Center and AusCERT (Australian Computer Emergency Response Team). printable version A. Introduction B. General Advice Pertaining to Intrusion Detection C. Look for Signs that Your System may have been Compromised 1. A Word on Rootkits 2. Examine Log Files 3. Check for Odd User Accounts and Groups 4. Check All Groups for Unexpected User Membership 5. Look for Unauthorized User Rights 6. Check for Unauthorized Applications Starting Automatically 7. Check Your System Binaries for Alterations 8. Check Your Network Configurations for Unauthorized Entries 9. Check for Unauthorized Shares 10. Check for Any Jobs Scheduled to Run 11. Check for Unauthorized Processes 12. Look Throughout the System for Unusual or Hidden Files 13. Check for Altered Permissions on Files or Registry Keys 14. Check for Changes in User or Computer Policies 15. Ensure the System has not been Joined to a Different Domain 16. Audit for Intrusion Detection 17. Additional Information D. Consider Running Intrusion Detection Systems If Possible 1. Freeware/shareware Intrusion Detection Systems 2. Commercial Intrusion Detection Systems E. Review Other AusCERT and CERT Documents 1. Steps for Recovering from a Windows NT Compromise 2. Windows NT Configuration Guidelines 3. NIST Checklists F. Document Revision History A. Introduction This document outlines suggested steps for determining whether your Windows system has been compromised. System administrators can use this information to look for several types of break-ins. We also encourage you to review all sections of this document and modify your systems to address potential weaknesses. -

Vbscripting For

Paper AD09 Integrating Microsoft® VBScript and SAS® Christopher Johnson, BrickStreet Insurance ABSTRACT VBScript and SAS are each powerful tools in their own right. These two technologies can be combined so that SAS code can call a VBScript program or vice versa. This gives a programmer the ability to automate SAS tasks, traverse the file system, send emails programmatically, manipulate Microsoft® Word, Excel, and PowerPoint files, get web data, and more. This paper will present example code to demonstrate each of these capabilities. Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Getting Started ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 VBScript Running SAS ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Creating and Running Code ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Running Existing Code .............................................................................................................................................. -

Lawrence A. Husick, Esq. Co-Chair, FPRI Center on Terrorism May 1, 2015 We Were Warned…

Cyberthreats: The New Strategic Battleground Lawrence A. Husick, Esq. Co-Chair, FPRI Center on Terrorism May 1, 2015 We were warned… “Electronic Pearl Harbor…is not going to be against Navy ships sitting in a Navy shipyard. It is going to be against commercial infrastructure.” Dep. Defense Secretary John Hamre, 1999 Unrestricted Warfare Cols. Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, People’s Liberation Army of China, 1999 Computer virus, worm, trojan Information poisoning Financial manipulation Direct cyberattack on US Based on US Strategic Concept of MOOTW (Military Operations Other Than War) CyberWar “There’s no agreed-on definition of what constitutes a cyberattack. It’s really a range of things that can happen, from exploitation and exfiltration of data to degradation of networks, to destruction of networks or even physical equipment…” - Dep. Defense Sec. Wm. J. Lynn, III, Oct. 14, 2010 Cyberdefense “There is virtually no effective deterrence in cyber warfare, since even identifying the attacker is extremely difficult and, adhering to international law, probably nearly impossible. - Dr. Olaf Theiler, NATO Operations China • PLA Unit 61398, located in Shanghai’s Pudong area • Attacked over 1,000 servers using 849 addresses • One victim was accessed for 4 years, 10 months • Largest single data theft: 6.5TB “The [Mandiant] report, … lacks technical proof. … Second, there is still no internationally clear, unified definition of what consists of a ‘hacking attack’. There is no legal evidence behind the report subjectively inducing that the everyday gathering of online (information) is online spying.” CyberThreat CyberCrime CyberSpying CyberWar CyberThreat CyberCrime CyberSpying CyberWar CyberThreat $ Data Disruption Also: • CyberEspionage • CyberTerrorism • CyberActivism • CyberAnarchy MAD to MUD (Gale & Husick, Feb. -

Attributing Cyber Attacks Thomas Rida & Ben Buchanana a Department of War Studies, King’S College London, UK Published Online: 23 Dec 2014

This article was downloaded by: [Columbia University] On: 08 June 2015, At: 08:43 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Strategic Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjss20 Attributing Cyber Attacks Thomas Rida & Ben Buchanana a Department of War Studies, King’s College London, UK Published online: 23 Dec 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Thomas Rid & Ben Buchanan (2015) Attributing Cyber Attacks, Journal of Strategic Studies, 38:1-2, 4-37, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2014.977382 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2014.977382 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

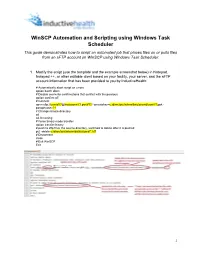

Winscp Automation and Scripting Using Windows Task Scheduler

WinSCP Automation and Scripting using Windows Task Scheduler This guide demonstrates how to script an automated job that places files on or pulls files from an sFTP account on WinSCP using Windows Task Scheduler. 1. Modify the script (use the template and the example screenshot below) in Notepad, Notepad ++, or other editable client based on your facility, your server, and the sFTP account information that has been provided to you by InductiveHealth: # Automatically abort script on errors option batch abort # Disable overwrite confirmations that conflict with the previous option confirm off # Connect open sftp://userid??@hostname??:port#??/ -privatekey=c:\directory\where\key\stored\user??.ppk - passphrase=?? # Change remote directory cd cd /incoming # Force binary mode transfer option transfer binary # push to sftp from the source directory, switched to delete after it is pushed put -delete c:\directory\where\data\stored\*.hl7 # Disconnect close # Exit WinSCP Exit @hostname??:port#?? 1 2. With the script file edited and localized to your needs, the next step is to automate a command line method to run the script. There are multiple methods of how this can be accomplished. We will provide guidance on one of those methods: Using the “Start a Program” within Windows Task Scheduler. Step 1: Create a new task in Windows Task Scheduler Step 2: Schedule the triggers Step 3: Create a new action: Start a program Step 4: Settings: Program/script should aim at the WinSCP.com installed on the machine Step 5: Add argument should read: /script=NameOfScript.txt Optional, if generation of a log file is preferred, include the log switch: /script=NameOfScript.txt /log=NameOfLog.log Step 6: Start in is the default directory for the task to look for the script and log files.