An Historical Examination of the Influences of Satellite Radio and Internet Radio on Shortwave Broadcasting Since the End of the Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of Television. Television and Its Importance for the History of Health and Medicine Jessica Borge, Tricia Close-Koenig, Sandra Schnädelbach

Introduction: The Science of Television. Television and its Importance for the History of Health and Medicine Jessica Borge, Tricia Close-Koenig, Sandra Schnädelbach To cite this version: Jessica Borge, Tricia Close-Koenig, Sandra Schnädelbach. Introduction: The Science of Television. Television and its Importance for the History of Health and Medicine. Gesnerus, Schwabe Verlag Basel, 2019, 76 (2), pp.153-171. 10.24894/Gesn-en.2019.76008. hal-02885722 HAL Id: hal-02885722 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02885722 Submitted on 30 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Gesnerus 76/2 (2019) 153–171, DOI: 10.24894/Gesn-en.2019.76008 Introduction. The Science of Television: Television and its Importance for the History of Health and Medicine Jessica Borge, Tricia Close-Koenig, Sandra Schnädelbach* From the live transmission of daunting surgical operations and accounts of scandals about medicines in the 1950s and 1960s to participatory aerobic workouts and militant AIDS documentaries in the 1980s the interrelation- ship of the history of bodies and health on television and the history of tele- vision can be witnessed. A telling example of this is the US born aerobics movement as it was brought to TV in Europe, with shows such as Gym Tonic (from 1982) in France, Enorm in Form (from 1983) in Germany or the Green Goddess on BBC Breakfast Time (from 1983) in Great Britain. -

Micro-Broadcasting: License-Free Campus Radio in This Issue: • Carey Junior High School ARC • WEFAX Reception on an Ipad • MT Reviews: MFJ Mini-Frequency Counter

www.monitoringtimes.com Scanning - Shortwave - Ham Radio - Equipment Internet Streaming - Computers - Antique Radio ® Volume 30, No. 9 September 2011 U.S. $6.95 Can. $6.95 Printed in the United States A Publication of Grove Enterprises Micro-Broadcasting: License-Free Campus Radio In this issue: • Carey Junior High School ARC • WEFAX Reception on an iPad • MT Reviews: MFJ Mini-Frequency Counter CONTENTS Vol. 30 No. 9 September 2011 CQ DX from KC7OEK .................................................... 12 www.monitoringtimes.com By Nick Casner K7CAS, Cole Smith KF7FXW and Rayann Brown KF7KEZ Scanning - Shortwave - Ham Radio - Equipment Internet Streaming - Computers - Antique Radio Eighteen years ago Paul Crips KI7TS and Bob Mathews K7FDL wrote a grant ® Volume 30, No. 9 September 2011 U.S. $6.95 through the Wyoming Department of Education that resulted in the establishment Can. $6.95 Printed in the United States A Publication of Grove Enterprises of an amateur radio club station at Carey Junior High School in Cheyenne, Wyoming, known on the air as KC7OEK. Since then some 5,000 students have been introduced to amateur radio; nearly 40 students have been licensed, and last year there were 24 students in the club, seven of whom were ready to test for their own amateur radio licenses. In this article, Carey Junior High School students Nick, Cole and Rayann, all three of whom have received their licenses, relate their experiences with amateur radio both on and off the air. While older hams many times their ages are discouraged Micro-Broadcasting: about the direction of the hobby, these students let us all know that the future of License-Free Campus Radio amateur radio is already in good hands. -

London Calling: BBC External Services, Whitehall and the Cold War 1944- 57

London calling: BBC external services, Whitehall and the cold war 1944- 57. Webb, Alban The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1577 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] LONDON CALLING: SSC EXTERNAL SERVICES, WHITEHALL AND THE COLD WAR, 1944-57 ALBAN WEBB Queen Mary College, University of London A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: '~"\ ~~Ue6b Alban Webb Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: Alban Webb ABSTRACT The Second World War had radically changed the focus of the BBC's overseas operation from providing an imperial service in English only, to that of a global broadcaster speaking to the world in over forty different languages. The end of that conflict saw the BBC's External Services, as they became known, re-engineered for a world at peace, but it was not long before splits in the international community caused the postwar geopolitical landscape to shift, plunging the world into a cold war. At the British government's insistence a re-calibration of the External Services' broadcasting remit was undertaken, particularly in its broadcasts to Central and Eastern Europe, to adapt its output to this new and emerging world order. -

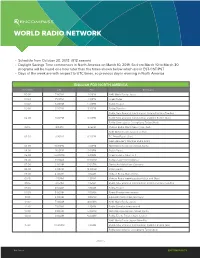

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

THE WORLD of SHORTWAVE BROADCASTING Glenn Hauser

THE WORLD OF SHORTWAVE BROADCASTING Glenn Hauser On Thu May 8 I heard the German at 2244 introduced as the program REE heard during the 21 UT hour on 17595 with new Portuguese for Monday, 17 December 2007! Do they just play out whatever old service to Brazil, including Spanish lessons. Collides with WEWN Eng- stuff? Unclean audio with distortion on sibilants, sharp gating like in lish, but depending on skip, can override it. Also airs earlier at 18-19 the old USSR days (Kai Ludwig, Germany, DXLD) on 17595 before WEWN comes on (gh, OK) O Espanhol no Brasil is RUSSIA Another shortwave site to go: Samara – Well-placed sources hint bilingual, partly in Spanish, M-F (Célio Romais, Panorama) that the Russian transmitter operator RTRS intends to close down its REE’s token newscast in ‘’Lenguas Co-Oficiales,” M-F 1240-1255, shortwave facilities at Samara, perhaps by the end of the current A08 best on 15170 via Costa Rica, was sometimes incomplete; supposed season. to be 1240 Catalan, 1245 Galician, and 1250 Basque. Catalan was If so, it would be the third shut-down of a major SW site in the sometimes missing, and Basque really in Castilian! Clásicos Populares former Soviet Union, after Brovary (Ukraine) and Yekaterinburg. And it from Radio Uno, is now Mon, Tue and Wed only at 1305-1400, best would by no means be a surprise. Just compare the amount of installed here on 15170, 17595 (gh, OK) capacity with the remaining demand for airtime, if not for Samara in SUDAN [non] Southern Sudan Interactive Radio Instruction, in English, new particular, for the facilities in European Russia altogether. -

Jan Karski Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf187001bd No online items Register of the Jan Karski papers Finding aid prepared by Irena Czernichowska and Zbigniew L. Stanczyk Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Jan Karski papers 46033 1 Title: Jan Karski papers Date (inclusive): 1939-2007 Collection Number: 46033 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: Polish Physical Description: 20 manuscript boxes, 11 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder, 6 card file boxes, 24 photo envelopes, and 26 microfilm reels(21.8 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, memoranda, government documents, bulletins, reports, studies, speeches and writings, printed matter, photographs, clippings, newspapers, periodicals, sound recordings, videotape cassettes, and microfilm, relating to events and conditions in Poland during World War II, the German and Soviet occupations of Poland, treatment of the Jews in Poland during the German occupation, and operations of the Polish underground movement during World War II. Includes microfilm copies of Polish underground publications. Boxes 1-34 also available on microfilm (24 reels). Video use copies of videotape available. Sound use copies of sound recordings available. Creator: Karski, Jan, 1914-2000 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives from 1946 to 2008. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Jan Karski papers, [Box no., Folder no. -

O, Nitoring a Publication of Game Enee + Rises

Vol. 15, No. 8 August 1996 Your Personal Communications Source ) . o, nitoring A Publication of Game Enee + rises, ing ómß Thl o hone I We Eher 08 MT Reviews Drake SW -1 Air Force Goes to Zulu Plan o 33932 74654 s z Giant List of Fast Food Freqs www.americanradiohistory.com The offers All Mode Communications Decoding. 46L72. 11Hz UCH: 103.5 Hz CTCSS Mode 461.725 MHz )C,:. E4i' DCS Mode 461 . ''ç, MHz Nearfield Receiver _ High Speed FM Communications )TMF: 8003279912 sweeps range of 30MHz to 2GHz in less than one DTMF Mode second Two line character LCD displays Frequency and either. Additional Display Modes: All Mode Decoding (CTCSS, DCS, DTMF), LTR-Trunk- Latitude/Longitude Mode ing. Relative Signal Strength, Latitude and Longitude, or Signal Strength Mode FM Deviation with automatic backlight Deviation Mode NMEA -0183 GPS Interface provides tagging data with LTR -Trunking Mode location for mapping applications* CI -v compliant Serial Data Interface with both TTL and RS232C levels Frequency Recording Memory Register logs 500 frequencies with Time, Date, Latitude, and Longitude information Real -Time Clock/Calander with battery back -up Frequency Lock Out, Manual Skip, and Auto or Manual Ho capability Tape Control Output with Tape Recorder Pause control relay and DTMF Encoder for audio data recording INNOVATIVE PRODUCT Rotary Encoder for easy selection of menus for setup Internal Speaker, Audio earphone/headphone jack FOR A MODERN Miniature 8 -pin DIN Serial Interface port for PC connection PLANET Relative ten segment Signal Strength Bargraph Mode Numerical Deviation Mode with 1 -10kHz and 10- 100kHz ranges - - ODUCTORY PRICE Includes Built -in Rapid Charge NiCad Batteries with 8 hour.dischargë: time and a Universal Power Supply *Software for mapping applications is planned by third party Software Design Companies. -

US-China Relations

U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Susan V. Lawrence Specialist in Asian Affairs August 1, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41108 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Summary The United States relationship with China touches on an exceptionally broad range of issues, from security, trade, and broader economic issues, to the environment and human rights. Congress faces important questions about what sort of relationship the United States should have with China and how the United States should respond to China’s “rise.” After more than 30 years of fast-paced economic growth, China’s economy is now the second-largest in the world after that of the United States. With economic success, China has developed significant global strategic clout. It is also engaged in an ambitious military modernization drive, including development of extended-range power projection capabilities. At home, it continues to suppress all perceived challenges to the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. In previous eras, the rise of new powers has often produced conflict. China’s new leader Xi Jinping has pressed hard for a U.S. commitment to a “new model of major country relationship” with the United States that seeks to avoid such an outcome. The Obama Administration has repeatedly assured Beijing that the United States “welcomes a strong, prosperous and successful China that plays a greater role in world affairs,” and that the United States does not seek to prevent China’s re-emergence as a great power. -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

The Life and Times of a Czech-Born Broadcaster Who Became An

BRIDSH I CZECH AND SLOVAK REUIE/J The life and times of a Czech-born broadcaster who became an English knight by Angela Spindler-Brown John Tusa, Making a Noise, Getting it Right, Getting it Wrong in Life, Broadcasting and the Arts 'TUSA Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2018 ISBN 978 1 47 460708 7 or many in London John Tusa, and partly financed by the Foreign Office. Newsnight presenter and manag He insists that any service, especially the ing director BBC World Service BBC can only be changed if one loves between 1980-1993, has been a what it does and wants to strengthen it and FCzech with perfect,faultless English, both improve it. spoken and written, and impeccable man And the World Service did go from ners. But his autobiography Making a strength to strength under his manage Noise says very little about his Czech her ment. He says that he "was the first man itage for there isn't much to tell. aging director who could say that he knew He came to London as a three-year-old what was being broadcast in Britain's boy, escaping with his mother from the name in languages other than English." Nazis as Czechoslovakia was being occu He demanded that the foreign language pied in 1939. His father, director of Bata broadcasts say exactly the same as the shoe enterprises, set up their English original news in English. home in a detached house in east Essex However unexpected issues were and Czechoslovakia was left behind. encountered when precise translations English became the language to be from English were to be made in the 37 used: "Officially we didn't speak Czech at languages the BBC broadcast to the C,n,n� It Right, Gettin); It Wrong home. -

Digitalization of Radio Through DRM Standard on Mediumwave And

ISSN: 2277-3754 ISO 9001:2008 Certified International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology (IJEIT) Volume 3, Issue 9, March 2014 Digitalization of Radio through DRM Standard on Mediumwave and Shortwave Branimir Jaksic, Mile Petrovic, Petar Spalevic, Ratko Ivkovic, Sinisa Minic University of Prishtina, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia University of Prishtina, Teachers College, Leposavic, Serbia areas where analog technology AM (amplitude modulation) Abstract— this paper work offers an overview of DRM was used. It is planned that AM should be replaced with standards used in digitization of radio on medium and short waves digital technology which is similar to technologies DAB and in the world. Firstly, it provides the raw characteristics of DRM DVB-T (all of these listed technologies use OFDM technology and its working principle, with a special focus on audio coding. After that, the state of DRM transmissions in modulation) [3]. The primary purpose of DRM technology is February 2014 is given. Also it gives an summary of radio stations for transfer of the audio content. With this basic purpose, which broadcast the program using DRM technology (country DRM also supports the transfer of some multimedia content and language transmission). Broadcasting areas of radio stations with lower transmission capacity: are also provided, as well as the number of active DRM - DRM text messages; frequencies by regions of the world, for each radio station - EPG (Electronic Program Guide); separately. Then, a map of DRM transmitters in the world is - Information text services (Journaline text based shown, with their main characteristics. information service); - Transmission frames (Slideshow); Index Terms—DRM, frequencie, radio channel, transmitters. -

Radio's War Lifeline News New Creative Radio Formats

1940s Radio’s War With the television service closed for the duration, it was radio’s war and the BBC nearly lost it in the opening skirmishes. Listeners wrote in to complain about the new Home Service, which had replaced the National and Regional programme services. There was criticism of too many organ recitals and public announcements. But the BBC had some secret weapons waiting in the wings. Colonel (‘I don’t mind if I do’) Chinstrap and Mrs (‘Can I do yer now, sir?’) Mopp were just of the two famous characters in Tommy Handley’s It’s That Man Again (ITMA) team. The comedian attracted 16 million listeners each week to the programme. This, and other popular comedy shows like Hi, Gang!, boosted morale during the war. Vera Lynn’s programme Sincerely Yours (dismissed by the BBC Board of Governors with the words: "Popularity noted, but deplored.") won her the title of "Forces’ Sweetheart”. In 1940 the Forces programme was launched for the troops assembling in France. The lighter touch of this new programme was a great success with both the Forces and audiences at home. After the war it was replaced by the Light Programme which was modelled on the Forces Programme. Distinguished correspondents, including Richard Dimbleby, Frank Gillard, Godfrey Talbot and Wynford Vaughan- Thomas, helped to attract millions of listeners every night with War Report, which was heard at the end of the main evening news. We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets…we shall never surrender.