Miami in 1876

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tubas Seek Respect Minor-Major (Slashing, Fighbng), 13:35; Millar,' Va

20—MANCHESTER h e r a l d . Thursday, Dec. 20. 1990 SCOREBOARD FRIDAY Hockey Basketball Placekickor-Morion Andersen, New Or leans. Kick returner—Mel Gray, DetroiL LOCAL NEWS INSIDE NHL standings NBA standings Special loams—Reyna Thompson, N.Y. ACTUALLY Giants. WALES CONFERENCE EASTERN CONFERENCE 1 Need player-To bo named later by head m Manager powers should be limited. Ritrlck Division Atlantic Division 6REAT“ i T . r I EM coach. W L T P ti GF GA W 1L Pci. GB NY Rangers 20 12 5 45 141 113 Boston 20 4 .833 m IN THE 1^ OF Philadelphia 19 16 3 41 127 122 Philadelphia 16 8 .667 4 ■ Porter Library closes for good. New Jer sey PKEMBERANPDoNt 17 13 5 39 138 120 New Vbrk 11 12 .478 6'/2 Rec Hoop Washington 18 18 0 36 119 New Jersey ODD 111 9 14 .391 10»/2 ToOCd'EMASAlNTlL 0 o Pittsburgh 16 16 3 35 146 132 Vteshlngton 8 15 .348 11t/2 What's NY Islarxiers 11 17 4 26 89 114 Miami 5 18 .217 141/2 o ■ CASE hopeful for school chances. a DIvi.lon C.ntr.1 Division 7T|E2NI>FJANUM Adults Boston 18 11 5 41 114 109 Milwaukee 17 7 .708 Ansaldi's 66 (Doug Marshall 26, Kyle Dougan Montreal 16 16 4 36 112 114 Chicago 15 9 News .625 2 19) Trinity Covenant 61 (Fern Thomas 29, Ed Hartford ■ Bogue, Grady will vie in 8th House. 14 16 4 32 97 113 Detroit 15 9 .625 2 Huppo 17, Dave DeValvo 10) Buffalo 11 15 7 29 102 111 Atlanta 11 11 .500 5 Stylo 106 (Dave Milner 26, Gone Nolen 24, Quebec 8 21 7 23 101 154 Cleveland 11 14 .440 61/2 Wendell Williams 21, Grog Thonws 17, Duane CONFERENCE Charlotte 8 14 .364 8 Milner 13) Manchester Cycle 102 (Mark Rokos 1 Division Indiana 9 16 .360 81/2 27, Joe McGann 26, Ed Slaron 18, Kevin Local/Regional Section, Page 9. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Cape Florida Light by CHARLES M

Te test^t Cape Florida Light By CHARLES M. BROOKFIELD Along the southeast Florida coast no more cheery or pleasing sight glad- dened the heart of the passing mariner of 1826 than the new lighthouse and little dwelling at Cape Florida. Beyond the glistening beach of Key Bis- cayne the white tower rose sixty-five feet against a bright green backdrop of luxuriant tropical foliage. Who could foresee that this peaceful scene would be the setting for events of violence, suffering and tragedy? At night the tower's gleaming white eye followed the mariner as he passed the dangerous Florida Reef, keeping watch to the limit of its visibility. When in distress or seeking shelter from violent gales the light's friendly eye guided him into Cape Florida Channel to safe anchorage in the lee of Key Biscayne. From the beginning of navigation in the New World, vessels had entered the Cape channel to find water and wood on the nearby main. Monendez in 1567 must have passed within the Cape when he brought the first Jesuit missionary, Brother Villareal, to Biscayne Bay. Two centuries later, during the English occupation, Bernard Romans, assistant to His Majesty's Surveyor General, in recommending "stations for cruisers within the Florida Reef", wrote: "The first of these is at Cayo Biscayno, in lat. 250 35' N. Here we enter within the reef, from the northward . you will not find less than three fathoms anywhere within till you come abreast the south end of the Key where there is a small bank of 11 feet only, give the key a good birth, for there is a large flat stretching from it. -

Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 Toni Carrier University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Carrier, Toni, "Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 by Toni Carrier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Trevor R. Purcell, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Social Capital, Political Economy, Black Seminoles, Illicit Trade, Slaves, Ranchos, Wreckers, Slave Resistance, Free Blacks, Indian Wars, Indian Negroes, Maroons © Copyright 2005, Toni Carrier Dedication To my baby sister Heather, 1987-2001. You were my heart, which now has wings. Acknowledgments I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the many people who mentored, guided, supported and otherwise put up with me throughout the preparation of this manuscript. To Dr. -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Peninsula Villa for Sale USA, Florida, 33149 Key Biscayne

Peninsula Villa For Sale USA, Florida, 33149 Key Biscayne 31,900,000 € QUICK SPEC Year of Construction Bedrooms 5 Half Bathrooms 1 Full Bathrooms 6 Interior Surface approx 893 m2 - 9,619 Sq.Ft. Exterior Surface approx 3,358 m2 - 36,154 Sq.Ft Parking 6 Cars Property Type Single Family Home TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS Coined The 1000 Year House by renowned architect Charles Pawley. Strategically built on a 38k square feet peninsula with 480 feet of waterfront on prestigious Mashta Island. Unimpeded wide panoramic views of the ocean, Bill Baggs Park, Cape Florida Light House and Stiltsville. This 12k square feet home is comprised of 5 bedrooms/6.5 baths which include 2 master bedrooms, theater, gym, library and staff qtrs. Covered gazebo and massive terraces with a resort pool/spa. Protected deep water dock accommodates a 100 plus foot yacht. PROPERTY FEATURES BEDROOMS • Master Bedrooms - • Total Bedrooms - 5 • Suite - BATHROOMS • Full Bathrooms - 6 • Total Bathrooms - 6 • Half Bathrooms - 1 OTHER ROOMS • • Home Theater • Fitness Center & Spa • Family Room • Library • Great Room • Staff Quarters • Home Office • Deck & Dining Room • Staff Quarters • Wine Storage • Wine Cellar • • Home Office • INTERIOR FEATURES • • 1000 Year House By Renowned • Architect Charles Pawley • Harwood Flooring • • Marble Flooring • • EXTERIOR AND LOT FEATURES • • Located On Prestigious Mashta Island • Protected Deep Water Dock • 480 Ft Of Waterfront Accommodates A 100 Plus Foot Yacht • Water Access • Wide Open-Bay Views • Private Dock • Panoramic Views Of The Ocean, Bill • Boatliftcovered Gazebo Baggs Park, Cape Florida Light House • Massive Terraces And Stiltsville • Resort Pool/Spa HEATING AND COOLING • Heating Features: Central Heating • Cooling Features: Central A/C POOL AND SPA • • Heated Pool • LAND INFO GARAGE AND PARKING • Lot Size : 3,358 m2 - 36,154 Sq.Ft • Garage Spaces: 6 Cars • Parking Spaces: BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION • Living : 893 m2 - 9,619 Sq.Ft. -

The Viceroyalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of An

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 7-1-2016 The iceV royalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of an Imperial City John K. Babb Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000725 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Latin American History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Babb, John K., "The icV eroyalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of an Imperial City" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2598. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2598 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE VICEROYALTY OF MIAMI: COLONIAL NOSTALGIA AND THE MAKING OF AN IMPERIAL CITY A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by John K. Babb 2016 To: Dean John Stack Green School of International and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by John K. Babb, and entitled The Viceroyalty of Miami: Colonial Nostalgia and the Making of an Imperial City, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. ____________________________________ Victor Uribe-Uran ____________________________________ Alex Stepick ____________________________________ April Merleaux ____________________________________ Bianca Premo, Major Professor Date of Defense: July 1, 2016. -

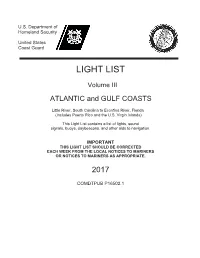

USCG Light List

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard LIGHT LIST Volume III ATLANTIC and GULF COASTS Little River, South Carolina to Econfina River, Florida (Includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) This /LJKW/LVWFRQWDLQVDOLVWRIOLJKWV, sound signals, buoys, daybeacons, and other aids to navigation. IMPORTANT THIS /,*+7/,67 SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE LOCAL NOTICES TO MARINERS OR NOTICES TO MARINERS AS APPROPRIATE. 2017 COMDTPUB P16502.1 C TES O A A T S T S G D U E A T U.S. AIDS TO NAVIGATION SYSTEM I R N D U 1790 on navigable waters except Western Rivers LATERAL SYSTEM AS SEEN ENTERING FROM SEAWARD PORT SIDE PREFERRED CHANNEL PREFERRED CHANNEL STARBOARD SIDE ODD NUMBERED AIDS NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED EVEN NUMBERED AIDS PREFERRED RED LIGHT ONLY GREEN LIGHT ONLY PREFERRED CHANNEL TO CHANNEL TO FLASHING (2) FLASHING (2) STARBOARD PORT FLASHING FLASHING TOPMOST BAND TOPMOST BAND OCCULTING OCCULTING GREEN RED QUICK FLASHING QUICK FLASHING ISO ISO GREEN LIGHT ONLY RED LIGHT ONLY COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) 9 "2" R "8" "1" G "9" FI R 6s FI R 4s FI G 6s FI G 4s GR "A" RG "B" LIGHT FI (2+1) G 6s FI (2+1) R 6s LIGHTED BUOY LIGHT LIGHTED BUOY 9 G G "5" C "9" GR "U" GR RG R R RG C "S" N "C" N "6" "2" CAN DAYBEACON "G" CAN NUN NUN DAYBEACON AIDS TO NAVIGATION HAVING NO LATERAL SIGNIFICANCE ISOLATED DANGER SAFE WATER NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY WHITE LIGHT ONLY MORSE CODE FI (2) 5s Mo (A) RW "N" RW RW RW "N" Mo (A) "A" SP "B" LIGHTED MR SPHERICAL UNLIGHTED C AND/OR SOUND AND/OR SOUND BR "A" BR "C" RANGE DAYBOARDS MAY BE LETTERED FI (2) 5s KGW KWG KWB KBW KWR KRW KRB KBR KGB KBG KGR KRG LIGHTED UNLIGHTED DAYBOARDS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY SPECIAL MARKS - MAY BE LETTERED NR NG NB YELLOW LIGHT ONLY FIXED FLASHING Y Y Y "A" SHAPE OPTIONAL--BUT SELECTED TO BE APPROPRIATE FOR THE POSITION OF THE MARK IN RELATION TO THE Y "B" RW GW BW C "A" N "C" Bn NAVIGABLE WATERWAY AND THE DIRECTION FI Bn Bn Bn OF BUOYAGE. -

Pop 2 a Second Packet for Popheads Written by Kevin Kodama Bonuses 1

Pop 2 a second packet for popheads written by Kevin Kodama Bonuses 1. One song from this album says “If they keep telling me where to go / I’ll blow my brains out to the radio”. For ten points each, [10] Name this sophomore album by Lorde. This Grammy-nominated album contains songs like “Perfect Places” and “Green Light”. ANSWER: Melodrama <Easy, 2/2> [10] Melodrama was created with the help of this prolific producer and gated reverb lover. This producer also worked on Norman Fucking Rockwell! with Lana del Rey and folklore with Taylor Swift. ANSWER: Jack Antonoff <Mid, 2/2> [10] This Melodrama track begins with documentary audio that remarks “This is my favorite tape!” and a Phil Collins drum sample. This song draws out the word “generation” after spelling the title phrase. ANSWER: “Loveless” (prompt on “Hard Feelings/Loveless”) <Hard, 2/2> 2. This artist's first solo release was an acid house track called "Dope". For ten points each, [10] Name this Kazakh producer who remixed a certain SAINt JHN song into a 2020 hit. This producer's bass effects are a constant presence in that song, which goes "You know I get too lit when I turn it on". ANSWER: Imanbek <Mid, 1/2> [10] That aforementioned song by SAINt JHN has this title and goes "Never sold a bag but look like Pablo in a photo". This is also the title of the final song in Carly Rae Jepsen's E•MO•TION Side B. ANSWER: "Roses" <Easy, 2/2> [10] After "Roses", Imanbek went on to sign with this producer's label Dharma. -

VIVA LA VOZ Committee Members Will Not Seek Re-Election

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 THURSDAY, AUGUST 22, 2019 DEALS OF THE Lynn eld will meet Western Avenue site$DAY$ about rail trail design slated for townhousesPG. 3 By Thor Jourgensen meeting, tentatively scheduled for 7 p.m. By Gayla Cawley and everyone felt the best use for that ITEM STAFF in the middle school. ITEM STAFF site would be residential,” said James “Based on the ballot referendum last Cowdell, EDIC/Lynn’sDEALS executive direc- LYNNFIELD — For the rst time in year, it should be fairly well attended,” LYNN — A $200,000 clean-up has tor. “We’re really happy that we were ve years the town is on target to host a said Crawford. turned a contaminated lot on Western able to clean up the siteOF and THE now turn it special town meeting with Sept. 26 the The last special town meeting was held Avenue into a place for new homes. into a residential project$ that everyone$ tentative date for debating $348,000 in in June 2014 to discuss the fate of the Economic Development and Industrial can be proud of.” DAY rail trail design spending. Centre Farm property in the town cen- Corp. of Lynn (EDIC/Lynn), the proper- If the development getsPG. the 3green light, Almost 300 residents signed a citizen ter. ty’s owner which last housed a gas sta- when completed, it would result in 16 petition circulated by the Friends of Crawford said the design estimate sub- tion 20 years ago, will soon enter into new townhouses and eight single-family Lynn eld Rail Trail to put trail design mitted in the petition mirrors trail de- an agreement with Lynn Housing Au- homes in the neighborhood. -

Seminole War

in Flori , > s^ OI»AIV i»* intended to represent the iiorrid Iflassacre of the Whites in I?i^..* 1 • T* I ^^«^ J -m % bruary 18&G, when near Four Htm. ne aboie I ^ ^^ f;m, clliWp£'"J lo„d«, in December 1835 and January a,dre ~ Ie« victims to the barbarity of the JJegroes and I^<IjJ ins. AN AUTHENTIC NARRATIVE OF THE ITS^ CAUSE, RISE AND PROGRESS, AND A MINUTE DETAIL OF THE HORRID MASSACRES Of the Whites, by the Indians and Negroes, in Florida, in the months of December, January and February. Communicated for the press by a gentleman who has spent eleven weeks in Florida, near the scene of the In dian depredations, and in a situation to collect every im portant fact relating thereto. ,! PROVIDENCE : i Printed for D. F. Blanchard, and others, Publishers, 1836. ' • ft 3 Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1836, by Daniel F. Blanchard, proprietor, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New-York. r SEMINOLE WAR. At the termination of the Indian War, in 1833, when, after much bloodshed, a treaty of peace was happily ef fected, and as was believed, firmly established between the American Government and Black Hawk and his fol lowers, it was then the opinion of many, that in conse quence of the severe chastisement received by the latter, that neither they or any of their red brethren would be found so soo^ manifesting- (by offensive operations) a dis position to disturb the repose of the white inhabitants of any of ouF frontier settlements—but, in this opinion, we have -

You're My Number One Vineright.Com

You're My Number One VineRight.com INTERMEDIATE 64 COUNT 4 WALL Choreographer Anna Spiteri ( Malta) Karen Kennedy (Scotland) Nuline Dance (Aug 2012) Music You're My Number One by S.Club 7 ( Miami 7 version) Album: S Club 7 – Best S Club 7 – The Greatest Hits (iTunes) INTRO; START FROM VOCALS SIDE ROCK, CROSS UNWIND FULL TURN LEFT, SIDE ROCK, BEHIND SIDE CROSS 1 -2 Step right to right side, recover on left 3 -4 Cross right over left, unwind full turn left (12 o’clock) 5 -6 Step left to left side, recover on right 7&8 Step left behind right, right to right side, cross left over right SIDE – TOGETHER, SHUFFLE BACK, SHUFFLE ½ , TURN LEFT STEP PIVOT ¼ LEFT 1 -2 Step right to right side, close left next to right 3&4 Step back right, close left next to right, step right back 5&6 Turn ¼ left stepping left to left side, (9) close right next to left, turn ¼ left stepping left Forward left ( 6 o’clock) 7 -8 Step forward right, pivot ½ turn left ( 12 o’clock) *Restart here 3rd wall CROSS POINT X 2, JAZZ BOX WITH SCRUFF 1 -2 Cross right over left, point left to left side 3 -4 Cross left over right, point right to right side 5 -6 Cross right over left , step back left 7 -8 Step right to right side, scruff left forward CROSS BACK, ¼ CHASSE, LEFT ROCKING CHAIR 1 -2 Cross left over right, step back right 3&4 Turn ¼ left stepping left to left side, close right next to left, left to left side ( 9 o’clock) 5 -6 Step right forward, recover on left 7 -8 Step back right, recover on left * Add 8 count tag here at 6th wall and restart SIDE ROCK, CROSS UNWIND FULL