Jesse Gamoran History Honors Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany" (2016). Student Publications. 434. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/434 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 434 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Abstract The aN zis utilized the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as anti-Semitic propaganda within their racial ideology. When the Nazis took power in 1933 they immediately sought to coordinate all aspects of German life, including sports. The process of coordination was designed to Aryanize sport by excluding non-Aryans and promoting sport as a means to prepare for military training. The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin became the ideal platform for Hitler and the Nazis to display the physical superiority of the Aryan race. However, the exclusion of non-Aryans prompted a boycott debate that threatened Berlin’s position as host. -

Cross Country Results Everything Ta En Into a ·Count

Supple enting TRACK & Fl LD NEWS twice monthly. Vol. 10, o. 8 ovember 20 , 1963 Page 57 Valeriy Brumel: My Coach Good Field Ready for NCAA Mee t by v aleny Brurnel (Reprinted from Soviet _\ eekly, courtesy Athletics Weekly) If all of the nation's top collegiate cross country runners show I met Vladimir Dyachkov in 1959, at the Central Sta dium in up at East Lansing for the CAA championships. ov. 25, it could be oscov, during the Soviet People's Games. I was doing badly and one of the fastest mass finishes in history. feeling fed up when thi s well-known trainer came up and assured me: San Jose State looks like the best bet for the team champion - "You'll jump '. You've all the attributes for it - vig or, temperament, ship but it's very difficultto pick an individual winner. As far as we boldness - but your technique i wron g. know T om O'Hara has not run a cross country race all season but he · ou '11 have to work very hard, and it's no good putting it off i& the defending CAA champion and could well repeat. Jim Keefe, until next summer. You must tart in the v inter .... ·· Jeff Fishback, and Vic Zwolak have all run in international com peti - At the end of the season I was included as a candidate for the tion. And then there is Danny Murphy, John Camiem, Ireland Sloan, USSR team , and the following January - Olympic year'. - met and Julio Marin (providing he runs) . -

2012 European Championships Statistics – Men's 100M

2012 European Championships Statistics – Men’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 9.99 1.3 Francis Obikwelu POR 1 Göteborg 20 06 2 2 10.04 0.3 Darren Campbell GBR 1 Budapest 1998 3 10.06 -0.3 Francis Obikwelu 1 München 2002 3 3 10.06 -1.2 Christophe Lemaitre FRA 1sf1 Barcelona 2010 5 4 10.08 0.7 Linford Christie GBR 1qf1 Helsinki 1994 6 10.09 0.3 Linford Christie 1sf1 Sp lit 1990 7 5 10.10 0.3 Dwain Chambers GBR 2 Budapest 1998 7 5 10.10 1.3 Andrey Yepishin RUS 2 Göteborg 2006 7 10.10 -0.1 Dwain Chambers 1sf2 Barcelona 2010 10 10.11 0.5 Darren Campbell 1sf2 Budapest 1998 10 10.11 -1.0 Christophe Lemaitre 1 Barce lona 2010 12 10.12 0.1 Francis Obikwelu 1sf2 München 2002 12 10.12 1.5 Andrey Yepishin 1sf1 Göteborg 2006 14 10.14 -0.5 Linford Christie 1 Helsinki 1994 14 7 10.14 1.5 Ronald Pognon FRA 2sf1 Göteborg 2006 14 7 10.14 1.3 Matic Osovnikar SLO 3 Gö teborg 2006 17 10.15 -0.1 Linford Christie 1 Stuttgart 1986 17 10.15 0.3 Dwain Chambers 1sf1 Budapest 1998 17 10.15 -0.3 Darren Campbell 2 München 2002 20 9 10.16 1.5 Steffen Bringmann GDR 1sf1 Stuttgart 1986 20 10.16 1.3 Ronald Pognon 4 Göteb org 2006 20 9 10.16 1.3 Mark Lewis -Francis GBR 5 Göteborg 2006 20 9 10.16 -0.1 Jaysuma Saidy Ndure NOR 2sf2 Barcelona 2010 24 12 10.17 0.3 Haralabos Papadias GRE 3 Budapest 1998 24 12 10.17 -1.2 Emanuele Di Gregorio IA 2sf1 Barcelona 2010 26 14 10.18 1.5 Bruno Marie -Rose FRA 2sf1 Stuttgart 1986 26 10.18 -1.0 Mark Lewis Francis 2 Barcelona 2010 -

1974 Age Records

TRACK AGE RECORDS NEWS 1974 TRACK & FIELD NEWS, the popular bible of the sport for 21 years, brings you news and features 18 times a year, including twice a month during the February-July peak season. m THE EXCITING NEWS of the track scene comes to you as it happens, with in-depth coverage by the world's most knowledgeable staff of track reporters and correspondents. A WEALTH OF HUMAN INTEREST FEATURES involving your favor ite track figures will be found in each issue. This gives you a close look at those who are making the news: how they do it and why, their reactions, comments, and feelings. DOZENS OF ACTION PHOTOS are contained in each copy, recap turing the thrills of competition and taking you closer still to the happenings on the track. STATISTICAL STUDIES, U.S. AND WORLD LISTS AND RANKINGS, articles on technique and training, quotable quotes, special col umns, and much more lively reading complement the news and the personality and opinion pieces to give the fan more informa tion and material of interest than he'll find anywhere else. THE COMPREHENSIVE COVERAGE of men's track extends from the Compiled by: preps to the Olympics, indoor and outdoor events, cross country, U.S. and foreign, and other special areas. You'll get all the major news of your favorite sport. Jack Shepard SUBSCRIPTION: $9.00 per year, USA; $10.00 foreign. We also offer track books, films, tours, jewelry, and other merchandise & equipment. Write for our Wally Donovan free T&F Market Place catalog. TRACK & FIELD NEWS * Box 296 * Los Altos, Calif. -

BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera UOMINI 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA), Andre De Grasse (CAN) 2012 Usain Bolt (JAM), Yohan Blake (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA) 2008 Usain Bolt (JAM), Richard Thompson (TRI), Walter Dix (USA) 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA), Francis Obikwelu (POR), Maurice Greene (USA) 2000 Maurice Greene (USA), Ato Boldon (TRI), Obadele Thompson (BAR) 1996 Donovan Bailey (CAN), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Ato Boldon (TRI) 1992 Linford Christie (GBR), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Dennis Mitchell (USA) 1988 Carl Lewis (USA), Linford Christie (GBR), Calvin Smith (USA) 1984 Carl Lewis (USA), Sam Graddy (USA), Ben Johnson (CAN) 1980 Allan Wells (GBR), Silvio Leonard (CUB), Petar Petrov (BUL) 1976 Hasely Crawford (TRI), Don Quarrie (JAM), Valery Borzov (URS) 1972 Valery Borzov (URS), Robert Taylor (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM) 1968 James Hines (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM), Charles Greene (USA) 1964 Bob Hayes (USA), Enrique Figuerola (CUB), Harry Jeromé (CAN) 1960 Armin Hary (GER), Dave Sime (USA), Peter Radford (GBR) 1956 Bobby-Joe Morrow (USA), Thane Baker (USA), Hector Hogan (AUS) 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA), Herb McKenley (JAM), Emmanuel McDonald Bailey (GBR) 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA), Norwood Ewell (USA), Lloyd LaBeach (PAN) 1936 Jesse Owens (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Martinus Osendarp (OLA) 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Arthur Jonath (GER) 1928 Percy Williams (CAN), Jack London (GBR), Georg Lammers (GER) 1924 Harold Abrahams (GBR), Jackson Scholz (USA), Arthur -

GERMANY from 1896-1936 Presented to the Graduate Council

6061 TO THE BERLIN GAMES: THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT IN GERMANY FROM 1896-1936 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science By William Gerard Durick, B.S. Denton, Texas May, 1984 @ 1984 WILLIAM GERARD DURICK All Rights Reserved Durick, William Gerard, ToThe Berlin Games: The Olympic Movement in Germany From 1896-1936. Master of Science (History), May, 1984, 237epp.,, 4 illustrations, bibliography, 99 titles. This thesis examines Imperial, Weimar, and Nazi Ger- many's attempt to use the Berlin Olympic Games to bring its citizens together in national consciousness and simultane- ously enhance Germany's position in the international com- munity. The sources include official documents issued by both the German and American Olympic Committees as well as newspaper reports of the Olympic proceedings. This eight chapter thesis discusses chronologically the beginnings of the Olympic movement in Imperial Germany, its growth during the Weimar and Nazi periods, and its culmination in the 1936 Berlin Games. Each German government built and improved upon the previous government's Olympic experiences with the National Socialist regime of Adolf Hitler reaping the benefits of forty years of German Olympic participation and preparation. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 0 0 - LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS....... ....--.-.-.-.-.-. iv Chapter I. ....... INTRODUCTION "~ 13 . 13 II. IMPERIAL GERMANY AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES . 42 III. SPORT IN WEIMAR GERMANY . - - IV* SPORT IN NAZI GERMANY. ...... - - - - 74 113 V. THE OLYMPIC BOYCOTT MOVEMENTS . * VI. THE NATIONAL SOCIALISTS AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES .... .. ... - - - .- - - - - - . 159 - .-193 VII. THE OLYMPIC SUMMER . - - .- -. - - 220 VIII. -

Progression of the European Outdoor Records

Progresión de los Récords de Europa al Aire Libre Progression of the European Outdoor Records (cerrado a / as at 31.10.2016) Revisado, completado, corregido y actualizado Revised, completed, corrected and updated Por/by José María García “A los admirados atletas europeos de todas las épocas y a Devoted to all the admired european athletes of all time, mis estimados colegas estadísticos, españoles y extranjeros, and to my respected colleagues in statistics, both spaniards con los que me he relacionado en el último medio siglo”. and foreign, whom I have met in the last half century. Introducción Introduction Permitidme unas breves líneas como introducción a la Allow me a few brief lines as an introduction to the list cronología de récords y mejores marcas de Europa que tengo of records and European best performances which I am ho- el honor de presentar. noured to present. En primer lugar tengo que manifestar algo obvio; se trata In the first place I have to state the obvious: it is a list de una lista de marcas con un breve suplemento, y no de un re- of performances with a brief supplement and not a story, nor lato -ni siquiera muy resumido- de la historia del atletismo eu- even a summary, of the history of European athletics (the Ita- ropeo (de ello ya se ocuparon en su día, con la debida lian experts Roberto Quercetani and Luciano Serra – and the extensión, entre otros, los expertos italianos Roberto Querce- Frenchman Gaston Meyer – among others in their day took tani y Luciano Serra- y el francés Gaston Meyer-, en los años care of that with due extent in the Sixties). -

Masters Athletes

Eugeniusz Piasecki University School of Physical Education in Poznań Krzysztof Kusy Jacek Zieliński MASTERS ATHLETICS Social, biological and practical aspects of veterans sport Poznań 2006 TRANSLATION FROM POLISH INTO ENGLISH MAGDALENA STEFAŃSKA-STEVEN (Foreword, Authors’ note, Chapters 1, 2, 3 and 4) AGNIESZKA KOSARZYCKA (Chapters 8 and 10) KATARZYNA SŁAWIŃSKA (Chapters 7 and 9) ZBIGNIEW NADSTOGA (Chapters 5 and 6) PUBLISHING COMMITTEE Stefan Bosiacki, Lechosław B. Dworak, Tomasz Jurek, Piotr Krutki, Wojciech Lipoński, Bogusław Marecki, Hanna Mizgajska-Wiktor, Wiesław Osiński, Łucja Pilaczyńska-Szcześniak (chairwoman), Marek Stuczyński REVIEWER Dieter Massin EDITOR Wiesława Parzy COMPUTER TYPESETTING Ewa Rajchowicz PHOTOGRAPHS Karl-Heinz Flucke COVER DESIGN Krystyna Gurtowska Arkadiusz Kosmaczewski Krzysztof Kusy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior written permission of the owner of the rights/publisher. Copyright © by Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego im. Eugeniusza Piaseckiego (Eugeniusz Piasecki University School of Physical Education) ul. Królowej Jadwigi 27/39, 61-871 Poznań, Poland BOOK SERIES: MONOGRAPH no. 372 ISBN 83-88923-69-2 ISSN 0239-7161 The Publishing Department. Order no. 7/06 Contents Foreword ......................................................................................... 5 Authors’ note .................................................................................. -

World Rankings — Men's Hammer

World Rankings — Men’s Hammer Oft-injured Koji Murofushi really spread out his 4 No. 1s, topping the charts in ’01, ’04, ’06 & ’10 © JIRO MOCHIZUKI/PHOTO RUN 1947 1949 1 ........................ Imre Németh (Hungary) 1 ........................ Imre Németh (Hungary) 2 ............................ Bo Ericson (Sweden) 2 .........Aleksandr Kanaki (Soviet Union) 3 .................... Ivan Gubijan (Yugoslavia) 3 ................ Karl Storch (West Germany) 4 ....................Karl Hein (West Germany) 4 .................... Karl Wolf (West Germany) 5 ................ Karl Storch (West Germany) 5 .................... Ivan Gubijan (Yugoslavia) 6 .................................. Bob Bennett (US) 6 ...............................Teseo Taddia (Italy) 7 ...... Jaroslav Knotek (Czechoslovakia) 7 .................................... Sam Felton (US) 8 ....Aleksandr Shekhtyel (Soviet Union) 8 ................................. Henry Dreyer (US) 9 .................... Karl Wolf (West Germany) 9 ...................... Sverre Strandli (Norway) 10 ................. Reino Kuivamäki (Finland) 10 .......................... Bo Ericson (Sweden) 1948 1950 1 ........................ Imre Németh (Hungary) 1 ........................ Imre Németh (Hungary) 2 ................ Karl Storch (West Germany) 2 ...................... Sverre Strandli (Norway) 3 .........Aleksandr Kanaki (Soviet Union) 3 ...............................Teseo Taddia (Italy) 4 ............................ Bo Ericson (Sweden) 4 ................ Karl Storch (West Germany) 5 ................... -

2014 European Championships Statistics – Men's 100M

2014 European Championships Statistics – Men’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 9.99 1.3 Francis Obikwelu POR 1 Göteborg 20 06 2 2 10.04 0.3 Darren Campbell GBR 1 Budapest 1998 3 10.06 -0.3 Francis Obikwelu 1 München 2002 3 3 10.06 -1.2 Christophe Lemaitre FRA 1sf1 Barcelona 2010 5 4 10.08 0.7 Linford Christie GBR 1qf1 Helsinki 1994 6 10.09 0.3 Linford Christie 1sf1 Sp lit 1990 6 10.09 -0.7 Christophe Lemaitre 1 Helsinki 2012 8 5 10.10 0.3 Dwain Chambers GBR 2 Budapest 1998 8 5 10.10 1.3 Andrey Yepishin RUS 2 Göteborg 2006 8 10.10 -0.1 Dwain Chambers 1sf2 Barcelona 2010 11 10.11 0.5 Darren Campbell 1sf2 Buda pest 1998 11 10.11 -1.0 Christophe Lemaitre 1 Barcelona 2010 13 10.12 0.1 Francis Obikwelu 1sf2 München 2002 13 10.12 1.5 Andrey Yepishin 1sf1 Göteborg 2006 13 7 10.12 -0.7 Jimmy Vicaut FRA 2 Helsinki 2012 16 8 10.13 1.1 Jaysuma Saidy Ndure NOR 1sf1 Helsinki 2012 17 10.14 -0.5 Linford Christie 1 Helsinki 1994 17 9 10.14 1.5 Ronald Pognon FRA 2sf1 Göteborg 2006 17 9 10.14 1.3 Matic Osovnikar SLO 3 Göteborg 2006 17 10.14 0.4 Christophe Lemaitre 1h3 Helsinki 2012 17 10.14 0.1 Christop he Lemaitre 1sf2 Helsinki 2012 22 10.15 -0.1 Linford Christie 1 Stuttgart 1986 22 10.15 0.3 Dwain Chambers 1sf1 Budapest 1998 22 10.15 -0.3 Darren Campbell 2 München 2002 25 11 10.16 1.5 Steffen Bringmann GDR 1sf1 Stuttgart 1986 25 10.16 1.3 Ronald Pognon 4 Göteborg 2006 25 11 10.16 1.3 Mark Lewis -Francis GBR 5 Göteborg 2006 25 10.16 -0.1 Jaysuma Saidy -

United States Bureau of Education Special

UNITED STATES BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1912, NO. 23 - - - WHOLE NUMBER 495 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS IN LIBRARIES IN THE UNITEDSTATES BY W. DAWSON JOHNSTON LIBRARIAN OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY and ISADORE G. MUDGE REFERENCE LIBRARIAN OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY -no WASHINGTON GOVERNMENTlitirrrugcofFicE ° 1912 0 CONfEN'I'S. Page. FOREWORD 3 GENERAL COLLECTIONS 5 Public documents, 5; nerspapers, 6.; directories, 9; almanacs, 9; in- cunabula, 10. PHILOSOPHY 11 Ethics, 11; psychology, 11 ;occult sIences, 11; witchcraft, 12. THEOLOGY 12 Exegetical theology, 13; church history, 15; by periOds, 16; by coun- tries, 17; by denominations,. 18; systematic theology, 28practical theology, non-Christian religions, 84. HISTORY 34 Numismatics, 84; biography, 34; genealogy, 34; Assyriology and re- lated subjects, 36; Jewish history, 36; Egypt, 38; Greece and Rome, 88; mediaeval history, 38; North America, 38; United States, 40; Indian tribes, 41; colonial period, 41; period 1776-1865-Civil War, 42; period 1865 to date, 45; United States local history, 45 ; Canada, 53; West Indies, 53; Mexico, 53; South Ameica, 53; Europe, 54; Asia, 61; Africa. 63; Oceania, 64. GEOGRA PH Y 64 Voyages, 65; oceanology, 66. ANTHROPOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY 66 Folklore, 67; sports and amusements, 67. SOCIAL SCIENCES 68 Statistics, 69; economic theory and history, 70; labor trades unions, trusts, 71; transportation and communication, 72; commerce, 78; private finance, 74; public finance, 74. Socimoor 75 Family, marriage, woman, 76; secret societies, 75; charities, 76; criminology, 76; socialism, 48. POLITICALSCIENCE 77 Constitutions, 77; municipal government, 78; coloniesimmigration, 78; international relations, 78. LAW 78 FIDUCATION _N_ 79 Higher educlition. 79; Individual intAlti.,Ions, 80; secondary Mace- don, etc., 81; special educatiop, 81schools In the United Stawg. -

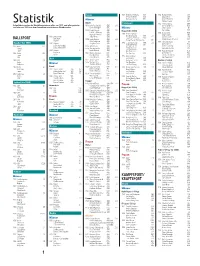

Statistik-Historisch.Pdf

Tennis 19 24 Wightman/Williams USA 19 52 Nathan Brooks USA Jessup/Richards USA Edgar Basel GER Männer Bouman/Timmer NED Anatoli Bulakow URS William Toweel RSA Statistik Einzel Tischtennis 1956 Terence Spinks GBR Aufgeführt werden die Medaillengewinner aller vor 1972 und aller geänder - 1896 John Pius Boland GBR 3:0 Mircea Dobrescu ROU ten oder vor 2016 aus dem Programm gestrichenen Wettbewerbe. Demis Kasdaglis GRE Männer John Caldwell IRL 19 00 Hugh Doherty GBR 3:0 Doppel (bis 2004) René Libeer FRA Harold S. Mahony GBR 1988 Chen Long-Can/ 1960 Gyula Török HUN Reginald Doherty GBR Sergej Siwko URS 1960 Jugoslawien 3:1 A.B.J. Norris GBR Wie Qing-Guang CHN 2:1 Lupulescu/Primorac YUG Kiyoshi Tanabe JPN BALLSPORT Dänemark 1908 Josiah Ritchie GBR 3:0 Abdelmoneim El Guindi EGY Ungarn An Jae Hyung/Yoo Nam-Kyu KOR Otto Froitzheim GER 1964 Fernando Atzori ITA Baseball (bis 2008) 1964 Ungarn 2:1 Vaughan Eaves GBR 1992 Lu Lin/Wang Tao CHN 3:2 Roßkopf/Fetzner GER Arthur Olech POL Tschechoslowakei Robert Carmody USA 1992 Kuba 11:1 1908 Arthur Gore GBR 3:0 Kang Hee Chan/ Deutschland (DDR) Stanislaw Sorokin URS Taiwan Halle George Caridia GBR Lee Chul Seung KOR Japan 1968 Ungarn 4:1 Josiah Ritchie GBR Kim Taek Soo/ 19 68 Ricardo Delgado MEX 1996 Kuba 13:9 Bulgarien 1912 Charles Winslow RSA 3:1 Yoo Nam Kyu KOR Arthur Olech POL Japan Servilio de Oliveira BRA Japan Harold Kitson RSA 1996 Kong Linghui/ USA Oscar Kreuzer GER Leo Rwabwogo UGA Golf Liu Guoling CHN 2000 USA 4:0 1912 Andre Gobert FRA 3:0 Wang Tao/Lu Lin CHN Bantam (-56 kg) Kuba Männer Halle Charles Dixon GBR Yoo Nam-Kyu/ 1920 Clarence Walker RSA Südkorea Anthony Wilding AUS Lee Chul-Seung KOR Chris J.