Draft for Consideration by Heads of Agency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Tier Reserve Background Report 2016File

Background Report Blue Tier Reserve www.tasland.org.au Tasmanian Land Conservancy (2016). The Blue Tier Reserve Background Report. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Tasmania Australia. Copyright ©Tasmanian Land Conservancy The views expressed in this report are those of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy and not the Federal Government, State Government or any other entity. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquires concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Front Image: Myrtle rainforest on Blue Tier Reserve - Andy Townsend Contact Address Tasmanian Land Conservancy PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, 827 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay TAS 7005 | p: 03 6225 1399 | www.tasland.org.au Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 1 Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Location and Access ................................................................................................................................ 4 Bioregional Values and Reserve Status .................................................................................................. -

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY ON PRIVATE LAND SERIES Wattles of the City of Whittlesea Over a dozen species of wattle are indigenous to the City of Whittlesea and many other wattle species are commonly grown in gardens. Most of the indigenous species are commonly found in the forested hills and the native forests in the northern parts of the municipality, with some species persisting along country roadsides, in smaller reserves and along creeks. Wattles are truly amazing • Wattles have multiple uses for Australian plants indigenous peoples, with most species used for food, medicine • There are more wattle species than and/or tools. any other plant genus in Australia • Wattle seeds have very hard coats (over 1000 species and subspecies). which mean they can survive in the • Wattles, like peas, fix nitrogen in ground for decades, waiting for a the soil, making them excellent cool fire to stimulate germination. for developing gardens and in • Australia’s floral emblem is a wattle: revegetation projects. Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) • Many species of insects (including and this is one of Whittlesea’s local some butterflies) breed only on species specific species of wattles, making • In Victoria there is at least one them a central focus of biodiversity. wattle species in flower at all times • Wattle seeds and the insects of the year. In the Whittlesea attracted to wattle flowers are an area, there is an indigenous wattle important food source for most bird in flower from February to early species including Black Cockatoos December. and honeyeaters. Caterpillars of the Imperial Blue Butterfly are only found on wattles RB 3 Basic terminology • ‘Wattle’ = Acacia Wattle is the common name and Acacia the scientific name for this well-known group of similar / related species. -

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests?

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements The Wilderness Society. 2020, Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? The State of the Nation’s RFAs, The Wilderness Society, Melbourne, Australia Table of contents 4 Executive summary Printed on 100% recycled post-consumer waste paper 5 Key findings 6 Recommendations Copyright The Wilderness Society Ltd 7 List of abbreviations All material presented in this publication is protected by copyright. 8 Introduction First published September 2020. 9 1. Background and legal status 12 2. Success of the RFAs in achieving key outcomes Contact: [email protected] | 1800 030 641 | www.wilderness.org.au 12 2.1 Comprehensive, Adequate, Representative Reserve system 13 2.1.1 Design of the CAR Reserve System Cover image: Yarra Ranges, Victoria | mitchgreenphotos.com 14 2.1.2 Implementation of the CAR Reserve System 15 2.1.3 Management of the CAR Reserve System 16 2.2 Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management 16 2.2.1 Maintaining biodiversity 20 2.2.2 Contributing factors to biodiversity decline 21 2.3 Security for industry 22 2.3.1 Volume of logs harvested 25 2.3.2 Employment 25 2.3.3 Growth in the plantation sector of Australia’s wood products industry 27 2.3.4 Factors contributing to industry decline 28 2.4 Regard to relevant research and projects 28 2.5 Reviews 32 3. Ability of the RFAs to meet intended outcomes into the future 32 3.1 Climate change 32 3.1.1 The role of forests in climate change mitigation 32 3.1.2 Climate change impacts on conservation and native forestry 33 3.2 Biodiversity loss/resource decline 33 3.2.1 Altered fire regimes 34 3.2.2 Disease 35 3.2.3 Pest species 35 3.3 Competing forest uses and values 35 3.3.1 Water 35 3.3.2 Carbon credits 36 3.4 Changing industries, markets and societies 36 3.5 International and national agreements 37 3.6 Legal concerns 37 3.7 Findings 38 4. -

Muelleria : an Australian Journal of Botany

Muelleria Volume 5 Number 1 March, 1982 NATIONAL HERBARIUM OF VICTORIA DEPARTMENT OF CROWN LANDS AND SURVEY Muelleria Volume 5, Number 1 March, 1982 CONTENTS Page A revision of the genus Templelonia R.Br. (Papilionaceae) — J. H. Ross 1 The nomenclature of some Australian lichens described as Lecanora and Placodium by Miiller-Argoviensis — R. W. Rogers 31 New Australian species of Nymphoides Seguier (Menyanthaceae) — Helen 1. Aston 35 Vegetation of East Gippsland — S. J. Forbes, N. G. Walsh and P. K. Gullan 53 A new Australian lichen: Cladonia sulcata — A. W. Archer 115 Editor: Helen 1. Aston Published by the National Herbarium of Victoria (MEL). Royal Botanic Gardens, South Yarra, Victoria 3141, Australia. D. M. Churchill, Director and Government Botanist. 43346/81 The date of publication of Volume 4, number 4, was 20 May 1981. A REVISION OF THE GENUS TEMPLETONIA R.Br. (PAPILIONACEAE) by J. H. Ross* ABSTRACT The endemic Australian genus Templetonia is revised. Eleven species are recognized and the uncertainty concerning the application of the name T. sulcata (Meissn.) Benth. is discussed. This discussion includes the selection ol a lectotype for Bossiaea rossii F. Muell., a possible synonym. Descriptions, a key to the identification of species, illustrations, and distribution maps are provided, together with notes on ecology and relationships. Two previous papers describing T. incana (.Muelleria 4: 247-249 (1980)) and T. negketa (loc. cit. 390-393 (1981)) should be used in conjunction with the present revision. INTRODUCTION Templetonia, a small genus of 1 1 species described by R. Brown in Ait. f Hort. , Kew. ed. 2, 4: 269 (1812), was named in honour of the Irish botanist John Templeton (1776-1825) ot Orange Grove, Belfast. -

Asteraceae), Cape Barren Island, Tasmania

Papers and Proceedings ofthe Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 140, 2006 35 ECOLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS ON A REMOTE MONTANE OCCURRENCE OF BEDFORD/A ARBORESCENS {ASTERACEAE), CAPE BARREN ISLAND, TASMANIA by Stephen Harris and Eve Lazarus (with six plates, six text-figures, three tables and one appendix) Harris, S. & Lazarus, E. 2006 (30:xi): Ecological observations on a remote montane occurrence of Bedfardia arborescens (Asteraceae), Cape Barren Island, Tasmania. Papers and Proceedings ofthe Royal Society of Tasmania 140: 35-48. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.140.35 ISSN 0080-4703. Biodiversity Conservation Branch, Department of Primary Industries and Water, GPO Box 44, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia (SH*, EL). *Au thor for correspondence. Bedfardia arborescens Hochr. is a tree listed under the Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 and is known in Tasmania only from an outlying population in cloud forest on Mt Munro, Cape Barren Island in the Furneaux Group. While the species is a common component of some rainforest and mixed forest in southeast mainland Australia, the outlying population on Cape Barren Island has apparently been eroded by a high fire frequency over the previous 200 years. The species occupies an ecological zone that is marginal to Atherosperma moschatum Labill.-dominated rainforest. Some stands occur adjacent to grasslands separated by a sharp ecological boundary. Even-aged cohorts represent the population structure on the mountain with no evidence of recent regeneration in or adjacent to any particular stand. A range of different aged cohorts occurs within the forest across the mountain. Mt Munro intercepts cloud moisture, resulting in the development of a cloud forest and a steep precipitation gradient between Mt Munro and the nearby coast. -

Three Capes Track

DRAFT DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Three Capes Track Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment ISBN 978-0-9871899-2-9 (print version) ISBN 978-0-9871899-3-6 (pdf version) © State of Tasmania 2011 Cover image: Cape Pillar by Joe Shemesh Published by: Parks and Wildlife Service Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 1751 Hobart TAS 7001 Cite as: Parks and Wildlife Service 2011, Draft Three Capes Track Development Proposal and Environmental Management Plan, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart CONTENTS Forward ............................................................................................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary..........................................................................................................................................................................ii 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Current Status of the Proposal ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Approvals Process -

The Discovery of 2,5-Dialkylcyclohexan-1,3-Diones As a New Class of Natural Products

The discovery of 2,5-dialkylcyclohexan-1,3-diones as a new class of natural products S. Frankea, F. Ibarraa, C. M. Schulza, R. Twelea, J. Poldyb, R. A. Barrowb, R. Peakallc, F. P. Schiestld, and W. Franckea,1 aDepartment of Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, University of Hamburg, Martin-Luther-King-Platz 6, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany; bDepartment of Chemistry and cDepartment of Botany and Zoology, School of Biology, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia; and dInstitute of Systematic Botany, University of Zu¨rich, Zollikerstrasse 107, CH-8008 Zu¨rich, Switzerland Edited by Jerrold Meinwald, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, and approved March 31, 2009 (received for review January 22, 2009) Orchids employing sexual deceit attract males of their pollinator candidate compounds, followed by coupled gas chromatography/ species through specific volatile signals that mimic female-released mass spectrometry (GC/MS) to determine their chemical struc- sex pheromones. One of these signals proved to be 2-ethyl-5- tures. Confirmation of biological activity with synthetic com- propylcyclohexan-1,3-dione (chiloglottone1), a new natural prod- pounds during field bioassays was the final essential step (11–13). uct that was shown to be most important in the relations between A milestone in the understanding of thynnine wasp phero- orchids of the genus Chiloglottis, native to Australia, and corre- mones and the attractive principles of orchids that mimic them sponding pollinator species. Systematic investigations on the mass has been the identification of 2-ethyl-5-propylcyclohexan-1,3- spectrometric fragmentation pattern of 2,5-dialkylcyclohexan-1,3- dione, chiloglottone1, formerly called chiloglottone, as the de- diones identified key ions providing information about the struc- cisive compound involved in the chemical mimicry used by tures of the substituents at positions 2 and 5. -

Phytophthora Resistance and Susceptibility Stock List

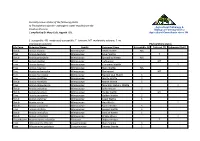

Currently known status of the following plants to Phytophthora species - pathogenic water moulds from the Agricultural Pathology & Kingdom Protista. Biological Farming Service C ompiled by Dr Mary Cole, Agpath P/L. Agricultural Consultants since 1980 S=susceptible; MS=moderately susceptible; T= tolerant; MT=moderately tolerant; ?=no information available. Phytophthora status Life Form Botanical Name Family Common Name Susceptible (S) Tolerant (T) Unknown (UnK) Shrub Acacia brownii Mimosaceae Heath Wattle MS Tree Acacia dealbata Mimosaceae Silver Wattle T Shrub Acacia genistifolia Mimosaceae Spreading Wattle MS Tree Acacia implexa Mimosaceae Lightwood MT Tree Acacia leprosa Mimosaceae Cinnamon Wattle ? Tree Acacia mearnsii Mimosaceae Black Wattle MS Tree Acacia melanoxylon Mimosaceae Blackwood MT Tree Acacia mucronata Mimosaceae Narrow Leaf Wattle S Tree Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Shrub Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Tree Acacia obliquinervia Mimosaceae Mountain Hickory Wattle ? Shrub Acacia oxycedrus Mimosaceae Spike Wattle S Shrub Acacia paradoxa Mimosaceae Hedge Wattle MT Tree Acacia pycnantha Mimosaceae Golden Wattle S Shrub Acacia sophorae Mimosaceae Coast Wattle S Shrub Acacia stricta Mimosaceae Hop Wattle ? Shrubs Acacia suaveolens Mimosaceae Sweet Wattle S Tree Acacia ulicifolia Mimosaceae Juniper Wattle S Shrub Acacia verniciflua Mimosaceae Varnish wattle S Shrub Acacia verticillata Mimosaceae Prickly Moses ? Groundcover Acaena novae-zelandiae Rosaceae Bidgee-Widgee T Tree Allocasuarina littoralis Casuarinaceae Black Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina paludosa Casuarinaceae Swamp Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina verticillata Casuarinaceae Drooping Sheoak S Sedge Amperea xipchoclada Euphorbaceae Broom Spurge S Grass Amphibromus neesii Poaceae Swamp Wallaby Grass ? Shrub Aotus ericoides Papillionaceae Common Aotus S Groundcover Apium prostratum Apiaceae Sea Celery MS Herb Arthropodium milleflorum Asparagaceae Pale Vanilla Lily S? Herb Arthropodium strictum Asparagaceae Chocolate Lily S? Shrub Atriplex paludosa ssp. -

Redalyc.ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER?

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica BACKHOUSE, GARY N. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 28- 43 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 28-43. 2007. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA GARY N. BACKHOUSE Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia [email protected] KEY WORDS:threatened orchids Australia conservation status Introduction Many orchid species are included in this list. This paper examines the listing process for threatened Australia has about 1700 species of orchids, com- orchids in Australia, compares regional and national prising about 1300 named species in about 190 gen- lists of threatened orchids, and provides recommen- era, plus at least 400 undescribed species (Jones dations for improving the process of listing regionally 2006, pers. comm.). About 1400 species (82%) are and nationally threatened orchids. geophytes, almost all deciduous, seasonal species, while 300 species (18%) are evergreen epiphytes Methods and/or lithophytes. At least 95% of this orchid flora is endemic to Australia. -

Draft Survey Guidelines for Australia's Threatened Orchids

SURVEY GUIDELINES FOR AUSTRALIA’S THREATENED ORCHIDS GUIDELINES FOR DETECTING ORCHIDS LISTED AS ‘THREATENED’ UNDER THE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION AND BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ACT 1999 0 Authorship and acknowledgements A number of experts have shared their knowledge and experience for the purpose of preparing these guidelines, including Allanna Chant (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Allison Woolley (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment), Andrew Brown (Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation), Annabel Wheeler (Australian Biological Resources Study, Australian Department of the Environment), Anne Harris (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), David T. Liddle (Northern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, and Top End Native Plant Society), Doug Bickerton (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), John Briggs (New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage), Luke Johnston (Australian Capital Territory Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate), Sophie Petit (School of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia), Melanie Smith (Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife), Oisín Sweeney (South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources), Richard Schahinger (Tasmanian Department of Primary Industry, Parks, Water and Environment). Disclaimer The views and opinions contained in this document are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and while reasonable care has been taken in its compilation, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. -

Ornatas Pilot Scale Lobster Hatchery, Nubeena

Environmental Consulting Options Tasmania ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF 31, 41 & 47 NUBEENA CRESCENT, TAROONA, TASMANIA Environmental Consulting Options Tasmania (ECOtas) for University of Tasmania 24 July 2018 Mark Wapstra ABN 83 464 107 291 28 Suncrest Avenue email: [email protected] phone: (03) 62 283 220 Lenah Valley, TAS 7008 web: www.ecotas.com.au mobile: 0407 008 685 ECOtas…providing options in environmental consulting ECOtas…providing options in environmental consulting CITATION This report can be cited as: ECOtas (2018). Ecological Assessment of 31, 41 & 47 Nubeena Crescent, Taroona, Tasmania. Report by Environmental Consulting Options Tasmania (ECOtas) for University of Tasmania, 24 July 2018. AUTHORSHIP Field assessment: Mark Wapstra Report production: Mark Wapstra Habitat and vegetation mapping: Mark Wapstra Base data for mapping: TheList Digital and aerial photography: Mark Wapstra, GoogleEarth, TheList ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Neal Denning (Associate Director, Strategy and Policy, University of Tasmania) provided background information and facilitated a guided tour of the subject titles. COVER ILLUSTRATION Looking into the consolidated patch of Eucalyptus globulus dry forest and woodland on 31 Nubeena Crescent. Please note: the blank pages in this document are deliberate to facilitate double-sided printing. Ecological Assessment of 31, 41 & 47 Nubeena Crescent, Taroona i ECOtas…providing options in environmental consulting Ecological Assessment of 31, 41 & 47 Nubeena Crescent, Taroona ii ECOtas…providing options in environmental consulting -

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.