A Framework for Campus Renewal and Physical Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University Daily Kansan

Volume 125 Issue 114 kansan.com Thursday, May 2, 2013 THE UNIVERSITY DAILY KANSAN UDKthe student voice since 1904 out DRINKING AT HOME ON THE ROAD EMILY DONOVAN cut is now accented with fuschia. At a March Madness watch party philosophy was ‘Anything that we their first stop in Colorado Springs, much as they would pay in a month [email protected] Devine first shaved a mohawk — or, three years ago, one of their friends can replace, let’s get rid of.’” they headed to a bar and found not for their commute when they both rather, “Jayhawk,” as it was originally mused about buying an RV and a Devine’s parents were intrigued; just a warm experience but the heart worked corporate jobs. Sometimes when Brian Devine blue and red for March Madness — national parks pass and touring the Scarpello’s, concerned. of the town: locals recommended Their two dogs, Ernie, a labra- looks in his rearview mirror, he in 2012. He recently reshaved it and country. Scarpello, who had always “Hey Dad,” Scarpello said, finally the perfect bike trails, restaurants dor/terrier mix from the Lawrence realizes, “Oh yeah, I’m driving my dyed it green, as recommended by daydreamed about flipping a school calling her parents during their vaca- and sightseeing spots. Humane Society, and Buddha, an h ou s e .” the 3-year-old son of a friend whose bus and going on tion in Florida a They’ve always praised the English bulldog who slobbers non- He and Maria Scarpello, nomadic driveway the couple had parked an adventure when few days before communities that brew craft beer stop that they “rescued” from living University alumni, have visited 288 their RV in. -

John Dillard Teaches Fencing As a Lifetime Activity

May 2016 Serving Active Seniors in the Lawrence-Topeka Area since 2001 Vol. 15, No. 11 INSIDE JJohnJJohnoohhnn DillardDDillardDiillllaarrdd KEVIN GROENHAGEN PHOTO KEVIN GROENHAGEN tteachestteacheseeaacchheess fencingffencingfeenncciinngg aasaasss aa lifetimellifetimeliiffeettiimmee aactivityaactivityccttiivviittyy SSeeSSeeeeee sstorysstoryttoorryy onoononn ppageppageaaggee tthreetthreehhrreeee The Spring 2016 issue of JAAA’s Amazing Aging is included in this month’s Senior Monthly. See inside. Business Card Directory ...24, 25 Calendar ..................................16 Estate Planning ......................14 Goren on Bridge .....................32 Health & Wellness.............12, 13 Humor ......................................28 Jill on Money ...........................15 Mayo Clinic .............................11 Memories Are Forever ...........31 Pet World .................................29 Puzzles and Games ................33 Rick Steves’ Europe ...............27 ENIO Wolfgang Puck’s Kitchen ........30 SprofileR Permit No. 19 No. Permit Lawrence, KS Lawrence, PAID U.S. Postage U.S. PRSRT STD PRSRT KAW VALLEY SENIOR MONTHLY May 2016 • 3 Dillard has taught fencing for nearly six decades By Kevin Groenhagen try, but it’s a different story in Europe,” Dillard said. “There’s not a lot of money ohn Dillard played football in high in it. The chancellor’s program allowed Jschool in Caldwell, Kan., but didn’t our fencing club to do intercollegiate have the size and skills to play at the competitions. I got in on the ground college level. However, he still had a fl oor as a freshman in college.” PHOTO KEVIN GROENHAGEN desire to participate in a sport when Interestingly, KU did have a fencing he entered the University of Kansas in program decades before Coach Giele 1957. He found what he was looking started a new program in 1957. In for while walking down a stairwell in fact, chances are you’ve heard of KU’s the student union. -

Open a Pdf of the Article

Phog Allen inside the Allen Fieldhouse crowd of 20,000 there in 1968, months before his assassination. World-famous entertainers have performed there, from Harry Belefon- te—who performed the first concert in Allen in November 1964—to Louis Armstrong, Ike and Tina Turner, Elton John, the Beach Boys and comedian Bob Hope. In 2004, President Bill Clinton spoke alongside former Kansas Sen. Robert Dole. The Fieldhouse hosted KU commencements when bad weather forced participants away from Memorial Stadium and indoors. It host- ed enrollment in the fall when students still pulled cards for classes. Two indoor track world records were set in the building. Vol- leyball, wrestling, even crew teams practiced there. All of the greatest athletes in KU’s rich his- tory—Wilt Chamberlain, Gale Sayers, Jim by Bob Luder, Ryun, Lynette Woodard—practiced or com- photos from Kenneth Spencer peted in the building that is commonly re- Research Library, University of Kansas ferred to as “the house that Wilt built.” Allen Fieldhouse has been everything to ev- Though not modern like many of eryone. “Allen Fieldhouse is considered the front porch of the University,” says John Novotny, the athletic venues across the country, who was associated with the university from 1966 through 1981 as an academic coun- its intimate atmosphere and selor, assistant athletic director and first Wil- liams Education Fund director. historic qualities are what make Of course, there’s what Allen Fieldhouse is mostly known for: the home of Jayhawks Allen Fieldhouse special. basketball. There are all of those great teams, play- ers and coaches (six of the eight who have As a junior at Salina Central High School, Richard Konzem wasn’t unlike most other wide-eyed farm kids grow- “Being a farm kid from Kansas … the limestone exterior and size of coached the Jayhawks did so in the field- ing up in central Kansas. -

Code of Honor Navajo Code Talker Chester Nez

No. 2, 2012 n $5 Code of Honor Navajo code talker Chester Nez n IRISH LITERATURE n HOSPITAL VIGILS Contents | March 2012 20 32 26 20 26 32 COVER STORY Luck of the Irish In the Moment Native Speaker A toast and tribute to KU’s KU Hospital volunteers oer world-class collection of Irish comfort and nd grace in their With a newly published literature. vigils with the dying. memoir, 91-year-old Chester Nez—one of the original 29 By Chris Lazzarino By Chris Lazzarino Navajo code talkers from World War II—looks back on a remarkable life. By Steven Hill Cover painting by Brent Learned Established in 1902 as e Graduate Magazine Volume 110, No. 2, 2012 ISSUE 2, 2012 | 1 Lift the Chorus and I count them among my conuence of the Kansas and must endure to bring violators closest friends. But when they Missouri rivers, with its halves to justice. don their black and gold, and distinguished by the state in She states that many pay congregate together in their which each is located. taxes, spend money and play a stadiums and eld houses, Now, what God hath joined, large role in the economy. e when they chant their silly the Missouri AD has torn role is largely negative as many MIZ-ZOU chant, they are asunder. Aer more than a send their money to their brash, unsportsmanlike bullies century of this union, Mizzou home country and do not pay and thugs. has divorced the Big 12, taxes, medical costs or car ey feel the same way about choosing a younger and richer insurance. -

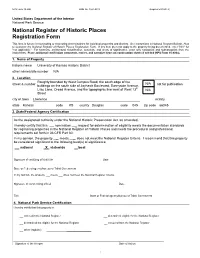

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A)

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2230 United States Department of the Interior ] National Park Service AUG2I I998 National Register of Historic Places i NAT REGISTER OF HISi'iiv o Registration Form NATIONAL PARK StRV This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Strong Hall__________________________________________________ other names/site number Administration Building___________________________ 2. Location 213 Strong Hall, University of Kansas, Jayhawk Drive and Poplar Lane street & number _______________________________________ D not for publication Lawrence city or town D vicinity Kansas KS Douglas A °45 -A 66045-1902 state ______ code county code ___ zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this JQQ&omination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

It's Election Time Pecks on the Beach

Highberger Schauner Bush It’s election time Chestnut Dever Maynard-Moody Vote for your candidates today in the election for city commissioners. 3A TUESDAY, APRIL 3, 2007 The student vOice since 1904 WWW.KANSAN.COM VOL. 117 ISSUE 125 PAGE 1A » CITY COMMISSION vigil Student voting numbers lag BY MATT ERICKSON commission primary, students voted are 18- to 24-years old. Campbell in dismally low numbers. said Precinct 10 regularly has the It prohibited indoor smoking in Douglas County cannot mea- county’s lowest voting rate in local almost all public places in Lawrence. sure precisely how many University elections. It’s the reason that more than three students vote, but Keith Campbell, The Precinct 10 voting site closed Students unrelated people cannot live togeth- county deputy of elections, said the early on the day of the February pri- gathered er in some areas of the city. During county’s data about 18- to 24-year- mary because only five of its nearly the next few years, it may give stu- old voters allowed for guesses about 2,000 registered voters showed up, Monday to dents easier ways to get to campus student voting. Campbell said. honor those and may impose more regulations The 10 Lawrence precincts that Katie Loyd, Lawrence junior, has killed in Iraq. on landlords. currently have the highest percent- made an effort to educate students 4A It is the city commission, and vot- age of 18- to 24-year-old registered about the city commission race in ers will choose its new lineup today. voters all had voting rates below her role as Student Senate com- softball But history suggests that University the county average in the 2003 and munity affairs director. -

Download The

PHOTO FINISH In six decades of shooting the Final Four, Rich Clarkson has shaped how we see the game BY BRIAN HENDRICKSON he dim basement resembles a library archive, not the sublevel of a home in suburban Denver. T Nondescript bankers’ boxes – 125 of them, each labeled in black marker – sit heavy on bookshelves circling a concrete floor. One reads “1972 Munich;” next to it, another is marked “1968 Mexico City.” On more shelves along nearby walls, stacks of old copies of the Topeka (Kan- sas) Capital-Journal and the Los Angeles Times rise in meticulous columns. A light table, once an essential tool for photographers, rests in the middle of the room surrounded by retired camera cases, a 30-year-old Macintosh and a generous magazine archive. Rich Clarkson buries his hands in one of those boxes, sifting through the hundreds of photo- The scope of Rich Clarkson’s graphs inside, searching for memories. He could reach into any one of these boxes and pull out a career can be seen in the display spellbinding shot: politicians, auto accidents, carnage from a tornado. of media credentials he keeps in his home office in Denver. JAMIE He draws out a photo of Stan Musial, close to retirement, hunched over and alone on the SCHWABEROW / NCAA PHOTOS Continued on page 48 STORIES FROM RICH CLarksON AS TOLD TO BRIAN HENDRICKSON Phog, in a fog The famous Phog Allen from Kansas is the most remarkable person I ever met. But he was the ultimate absent-minded professor. He would forget all kinds of things, and yet it was part of his charm. -

Phase One Drug’S Trial Signals Hope for Cancer Patients, New Era for KU Cancer Center

No. 5 ■ 2008 Phase One Drug’s trial signals hope for cancer patients, new era for KU Cancer Center ■ Olympian’s images ■ Ice-cream entrepreneur The stuff of legends The glory and tradition of championship This book is the story of three KU teams and their national championships, told by players and basketball in Allen Fieldhouse is legendary, sports journalists including Sports Illustrated’s but when Kansas teams advance to Grant Wahl. the Final Four—and win the national The photographs capture KU’s special moments. Photographer Rich Clarkson, j’55, covered all three championship—magic happens. of the championships—the first as a KU freshman in 1952. Now a publisher of fine commemorative books, Clarkson presents this special portfolio of KU’s shining moments, beautifully presented in 112 pages and capped by the iconic image of the 2008 title game—Mario Chalmers’ jumper with 3.7 seconds remaining. Published by the KU Alumni Association in an exclusive collaboration with Rich Clarkson and Associates. $40 Association Member | $45 Non Member (plus shipping) Order now to reserve your copy. Shipping will begin Dec. 1 in the order of reservations processed. www.kualumni.org | 800-584-2957 30 Contents Established in 1902 as The Graduate Magazine FEATURES One Athlete’s Olympics 30 Javelin thrower Scott Russell was hardly the only athlete to bring a camera to Beijing, but he wasn’t interested in point-and-shoot snapshots. Instead, Russell captured images worthy of the Olympics themselves: memorable. BY CHRIS LAZZARINO The Emperor of Ice Cream Bill Braum makes the ice cream that made his Braum’s 36 Ice Cream & Dairy Stores beloved in five Midwestern states. -

National Register Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name University of Kansas Historic District other names/site number N/A 2. Location Roughly bounded by West Campus Road, the south edge of the N/A street & number buildings on the south side of Jayhawk Boulevard, Sunnyside Avenue, not for publication th Lilac Lane, Oread Avenue, and the topographic line west of West 13 N/A Street city or town Lawrence vicinity state Kansas code KS county Douglas code 045 zip code 66045 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Page Turners Freshmen Embrace KU’S ‘Common Book’ Challenge

No 6, 2012 I $5 Page Turners Freshmen embrace KU’s ‘Common Book’ challenge I WOLF TRAP’S TERRE JONES I FORMER F DIC C HAIR SHEI LA BAIR Contents | November 2012 28 24 34 28 24 34 COVER STORY Street Fighter Art in the Parks By the Book As chairman of the FDIC, Wolf Trap director Terre Jones Sheila Bair was at the forefront marks his retirement with a e new “Common Book” of the U.S. government’s book and an ambitious program challenges freshmen response to the global nancial performance series that pays to ponder their place in the meltdown. Her new book homage to America’s national University community—inside details what went wrong and parks. and outside the classroom. how to stop it from happening again. By Jennifer Jackson Sanner By Chris Lazzarino By Steven Hill Established in 1902 as e Graduate Magazine Volume 110, No. 6, 2012 ISSUE 6, 2012 | 1 November 2012 76 Publisher Kevin J. Corbett, c’88 4 Lift the Chorus Editor Jennifer Jackson Sanner, j’81 Letters from our readers Creative Director Susan Younger, f’91 Associate Editors Chris Lazzarino, j’86 7 First Word Steven Hill e editor’s turn Editorial Assistant Karen Goodell Photographer Steve Puppe, j’98 8 On the Boulevard Graphic Designer Valerie Spicher, j’94 KU & Alumni Association events Communications Coordinator Lydia Krug Benda, j’10 10 Jayhawk Walk Advertising Sales Representative A skateboard champ, a mascot duel, an app David Johnston, j’94, g’06 for the apocalypse and more Editorial and Advertising Oce KU Alumni Association 1266 Oread Avenue 12 Hilltopics Lawrence, KS 66045-3169 News and notes: Colombian president Santos 785-864-4760 returns to Hill; business school to build new home. -

Jayhawks Will Pre- the Jayhawks Will Look for an Improved Effort Comics

THE STUDENT VOICE SINCE 1904 VOL. 116 ISSUE 17 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2005 WWW.KANSAN.COM t SAFETY t FINE ARTS Patrol checks drivers’ levels on the 1800 block of Kentucky Street be- Checkpoints tween 11 p.m. and 2 a.m. last Friday and Saturday, Ward said. aim to thwart Federal law requires the department to conduct a number of checkpoints because the city received $2.2 million in federal drunken driving funds for the traffic unit, Ward said. The department has completed more check- BY STEVE LYNN [email protected] points than required, he said. The entire traffic unit, which consists Kansan staff writer of seven vehicles, six officers and one ser- geant, will conduct a saturation patrol in Max Hire wasn’t sober when he saw Lawrence tonight, Ward said. Last week, the checkpoint ahead on Kentucky the traffic unit patrolled from 5 to 10 p.m. Street. He made a U-turn on a one-way on Friday. street to avoid it. The saturation patrol made 26 stops A police officer immediately pulled and gave out 10 speeding tickets, nine him over on 19th Street at 12:30 a.m. on moving violations and one seat belt vio- Sept. 3. lation, Ward said. The checkpoint yield- Hire, Kansas City, Mo., freshman, was ed four DWIs, one drug possession and one of four people charged with driving six minors-in-possession. while intoxicated last Friday and Satur- “It’s quite labor-intensive,” Ward said day night at a checkpoint on the 1800 of the checkpoint. “We have charge ve- block of Kentucky Street. -

Follow the Jayhawks 2017-18 Schedule Last Game

GAME FOUR CONTACT: Theresa Kurtz ([email protected]), Dayton Hammes ([email protected]) LADY HORNETS LADY 3-0 OVERALL 0-0 0-3 OVERALL 0-0 AP rank: -- USA Today rank: -- VS. AP rank: -- USA Today rank: -- JAYHAWKS Head Coach: Brandon Schneider Record: 418-185 Head Coach: Barbara Burgess Record: 25-88 2017-18 SCHEDULE JAYHAWKS AND HORNETS FACE OFF FOR FIRST TIME TALE OF THE TAPE Kansas women’s basketball continues nonconference action with its first matchup against Delaware State EXHIBITION GAMES in program history on Wednesday, Nov. 22 at 7 p.m., 10.29 Emporia State W, 69-49 inside Allen Fieldhouse. The game will be broadcast 11.5 Pittsburg State W, 57-50 on the Jayhawk Television Network/ESPN3 and the Jayhawk Radio Network. NONCONFERENCE 3-0 w-l 0-3 AROUND THE ARENA 11.12 Campbell W, 66-48 Kansas women’s basketball is celebrating Just Food N/A rank N/A 11.15 Texas Southern W, 72-37 Night. Fans that bring a non-perishable food item(s) 11.19 Yale W, 81-75 or a monetary donation will receive $5 admission to 11.22 Delaware State 7 p.m. 73.0 ppg 67.0 11.26 Rice 1 p.m. the game. 11.29 UMKC 7 p.m. 12.3 Arkansas 2 p.m. FAST BREAKS 43.1 fg% 36.3 12.6 Nebraska 7 p.m. • Wednesday’s matchup marks the first time that 12.10 Southeast Missouri 2 p.m. 34.4 3fg% 15.4 12.18 at St. John’s 6 p.m.