Have Fun Building a Bike Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carbusters 20

CARCARBustR- Editorial Collective: Tanja Eskola, Randy Ghent, Ste- ven Logan, Stephan von Pohl Other WCN Sta#: Arie Farnam (Fundraiser), Markus Heller and Jason Kirkpat- rick (Conference Coordinators), Roeland Kuijper (Ecotopia Bike- tour Coordinator), Lucie Lébrová (O!ce Manager), Maria Yliheikkilä (EVS intern) Contributing Writers: Arie Farnam, Sara Stout, Lisa Logan, Gabrielle Hermann, Ivan Gregov, Rob Zverina Contents Contributing Artists: Francois Meloçhe, Stig, Siris, Andy Singer 14 Awakening the Alliance Disability rights and the carfree movement Please send subscriptions, letters, articles, artwork, photos, feedback 17 How To Level a Curb and your life’s savings to: Fixing inequalities on the street Car Busters, Krátká 26 100 00 Prague 10, Czech Rep. 18 Bogotá Inspires the South tel: +(420) 274-810-849 fax: +(420) 274-816-727 Model spreads in Latin America and beyond [email protected] www.carbusters.org 19 Successful Road Fighting Submission deadline for issue 21: History of a grassroots movement in Berlin August 15, 2004. Reprints welcome with a credit to Car 22 The End of Space as We Know It? Busters and a reference to Carbusters. The ideology of spacism org. Subscription/membership info and coupon: page 29 and 30. ISSN: 1213-7154 / MK ÈR: E 100018 4 Letters 10 Action! A Hegelian Poem; Horse-free Cities; World Naked Bike Ride; Korean Printed in the Czech Republic on 100% recycled Carbusting Comrades; Sister Cities... Protests; European Bike Day... paper by VAMB. Pre-press by QT Studio. Distributed by Doormouse (Canada); AK Press, 6 Car Cult Review 19 Skill Sharing Desert Moon, Tower/MTS, and Ubiquity (US); INK (UK); and many others. -

Mountain Bike Performance and Recreation

sports and exercise medicine ISSN 2379-6391 http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/SEMOJ-SE-1-e001 Open Journal Special Edition “Mountain Bike Performance Mountain Bike Performance and and Recreation” Recreation Editorial Paul W. Macdermid, PhD* *Corresponding author Paul W. Macdermid, PhD Lecturer College of Health, School of Sport and Exercise, Massey University, Palmerston North, New College of Health Zealand School of Sport and Exercise Massey University Private Bag 11-222, Palmerston North 4474, New Zealand 1 The recreational activity of riding a bicyle off-road is very popular, and consequently Tel. +64 6 951 6824 2 E-mail: [email protected] a major contributor to tourism across the globe. As such the label accorded to the activity (“Mountain Biking (MTB)”), presents the image of an extreme sport. For many, this presents a Special Edition 1 picture of highly drilled and trained athletes performing gymnastic like tricks; hurtling down- Article Ref. #: 1000SEMOJSE1e001 hill at speeds >70 km/h (Downhill racing) or negotiating a short lap numerous times (Country Racing), to prove ascendancy over an opponent(s). For the majority of consumers/participants the French term “Velo Tout Terrain (VTT)” is a better decriptor and indicates the fact that the Article History bicycle is being purchased to ride on all terrain surfaces and profiles, by a diverse range of rd Received: August 23 , 2016 participants. Nevertheless, just like the world of motor car racing, technological development, rd Accepted: August 23 , 2016 physical understanding and skill development focuses on the very small percentage at the top of rd Published: August 23 , 2016 the pyramid in order to increase media exposure. -

City of Grand Rapids Bicycle Safety Education Project Study Phase Report

CITY OF GRAND RAPIDS BICYCLE SAFETY EDUCATION PROJECT STUDY PHASE REPORT Alta Planning + Design Grand Rapids, MI DRAFT - 2015 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................4 II. BEST PRACTICE REVIEW: BICYCLE EDUCATION CURRICULA. 8 III. PRIMARY RESEARCH FINDINGS ........................16 APPENDIX A: MEDIA CAMPAIGN FOCUS GROUP METHODOLOGY AND EXPANDED RESULTS .............22 APPENDIX B: MEDIA CAMPAIGN SCAN ...................44 APPENDIX C: CRASH ANALYSIS REPORT. .60 APPENDIX D: COUNTERMEASURE IDENTIFICATION ...78 APPENDIX E: BICYCLE CODE OF ORDINANCES REVIEW ......................................88 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS City of Grand Rapids Michigan Department of Transportation Project Executive Steering Committee Project Steering Committee Consultant Team: Alta Planning + Design Cairn Guidance Greater Grand Rapids Bicycle Coalition Güd Marketing Wondergem Consulting This page intentionally left blank. I. INTRODUCTION PROJECT OVERVIEW Project Structure The Project is divided into four phases: The ultimate long-term goal for the Bicycle Safety Education Project is to reduce the total number of Project Phase Description bicycle crashes, fatalities, and severity of injuries. The Study Phase The project team researched bicycle-car crash data project’s benefits will be multi-faceted. By broadening from Grand Rapids and all citizens’ knowledge of the rules of the road, it is the surrounding area to desired that more cooperative and lawful behavior look for contributing crash factors and patterns. The between cyclists and motorists will result. As more team reviewed bicycle people ride comfortably in traffic and feel safe, the safety education programs number of bicyclists that commute on a regular basis (both media campaigns and on-bike/in-person educational will increase and they will become more accepted as offerings) from other commu- viable road users. -

4-H Bicycling Project – Reference Book

4-H MOTTO Learn to do by doing. 4-H PLEDGE I pledge My HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, My HEALTH to better living, For my club, my community and my country. 4-H GRACE (Tune of Auld Lang Syne) We thank thee, Lord, for blessings great On this, our own fair land. Teach us to serve thee joyfully, With head, heart, health and hand. This project was developed through funds provided by the Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program (CAAP). No portion of this manual may be reproduced without written permission from the Saskatchewan 4-H Council, phone 306-933-7727, email: [email protected]. Developed in January 2013. Writer: Leanne Schinkel Table of Contents Introduction Objectives .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Getting the Most from this Project ....................................................................................................... 1 Achievement Requirements for this Project ..................................................................................... 2 Safety and Bicycling ................................................................................................................................. 2 Online Safety .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Resources for Learning ............................................................................................................................ -

Beginning Mountain Bike Racing in the Tricities TN/VA: Sweat and Gear Without Fear

Natasha Snyder [email protected] Beginning Mountain Bike Racing in the TriCities TN/VA: Sweat and Gear without Fear Natasha Snyder <[email protected]> Author Natasha Snyder and her beloved racing steed on a 35 mile training ride. Alvarado Station Store, Creeper Trail, Abingdon, VA. Natasha is a retired mountain bike racer from Bristol TN who specialized in cross country and cyclocross, with several trophy finishes. Natasha Snyder [email protected] The world of mountain bike racing is exciting, exhausting, varied—and accessible. If you are a competent mountain biking enthusiast who has mastered basic riding skills and built a decent level of fitness, you may be ready to explore the next step: the local racing circuit. With some readily available equipment and determination, you could begin collecting trophies in no time. Most adults who purchase a mountain bikes are simply recreational riders, looking to enjoy a comfortable, ecologically-sound, human-powered ride around their neighborhood or perhaps a quick ride to the beach during vacations. After all, mountain bikes are stylistically diverse, slower and safer than motorcycles, and more comfortable than skinny road bicycles. However, sometimes a casual rider becomes a true “enthusiast,” which is what people involved in bicycle racing call those who are more than recreational riders, but not quite elite athletes. Once the desire to go fast surpasses the desire to arrive home clean and comfortable, the time may have arrived for you to consider preparing to enter a local or amateur mountain bike race here in the Tri Cities and surrounding region. -

Blackstone Bicycle Works

Blackstone Bicycle Works Refurbished Bicycle Buyers Guide Always wear a helmet and make sure it fits! • Blackstone Bicycle Works sells donated bicycles that we refurbish and sell to help support our youth program. There are different types of bicycles that are good for different styles of riding. • What type of riding would you like to do on your new refurbished bicycle? Choosing Your Bicycle Types of Bicycles at Blackstone Bicycle Works The Cruiser Cruisers have a laid-back upright position for a more comfortable ride. Usually a single speed and sometimes has a coaster brake. Some cruisers also have internally geared hubs that can range from 3-speed and up. With smooth and some-times wider tires this bicycle is great for commuting and utility transport of groceries and other supplies. Add a front basket and rear rack easily to let the bike do the work of carrying things. Most cruisers will accept fenders to help protect you and the bicycle from the rain and snow. The Hybrid Bicycle A hybrid bicycle is mix of a road and mountain bicycle. These bicycles offer a range in gearing and accept wider tires than road bikes do. Some hybrids have a suspension fork while others are rigid. Hybrid bicycles are great for commuting in the winter months because the wider tires offer more stability. You can ride off-road, but it is not recommended for mountain bike trails or single-track riding. Great for gravel and a good all-around versatile bicycle. Great for utility, commuting and for leisure rides to and from the lake front. -

Bike Lanes, Edge Lines, and Vehicular Lane Widths

Review of Bike Lane, Edge Line 1 & Vehicular Lane Widths Bike Lanes, Edge Lines, and Vehicular Lane Widths DISCLAIMER This document provides information about the law as it pertains to on-road bicycle facilities on City of Burlington streets. This information is designed to help the City make informed decisions respecting bicycle planning and design matters. The reader is cautioned that the legal information presented herein is not the same as legal advice, which is the application of law to an individual's specific circumstances. To the best of our knowledge, this information is accurate and complete. However, we recommend that the City consult with their Legal Department to obtain professional assurance that our information, and the City’s interpretation of it, is appropriate to particular situations in Burlington. The authors of this document are not lawyers and the material presented herein is not, nor is it intended to be, a legal opinion or advice. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Marshall Macklin Monaghan Limited (MMM) in association with Intus Road Safety Engineering Incorporated (Intus), are pleased to present the findings of the Burlington Edge Line, Bike Lane and Vehicular Lane Width Study. In response to the growing popularity of cycling both as a recreational activity and as a utilitarian mode of transportation, the City of Burlington has taken a progressive approach in determining the best alternatives to provide its citizens with safe cycling routes. 1.1 BACKGROUND MMM and Intus were retained by the City to assist staff in evaluating current on-road bike facilities, and to provide assistance in reviewing the City’s existing bike lane standards for these facilities. -

Riding Tandem: Does Cycling Infrastructure Investment Mirror Gentrification and Privilege in Portland, OR and Chicago, IL?

Riding tandem: Does cycling infrastructure investment mirror gentrification and privilege in Portland, OR and Chicago, IL? Elizabeth Flanagan School of Urban Planning McGill University Room 400 Macdonald-Harrington Building 815 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Montréal, QC, Canada Phone (207) 805-2107 Email: [email protected] Ugo Lachapelle, PhD Département d’études urbaines et touristiques, École des sciences de la gestion, Université du Québec à Montréal, Case postale 8888, Succursale Centre-Ville, Montréal (Québec) H3C 3P8 Montréal, QC, Canada Phone: (514) 987-3000 x5141 Fax: (514) 987-7827 Email: [email protected] Ahmed El-Geneidy, PhD (Corresponding author) School of Urban Planning McGill University Room 400 Macdonald-Harrington Building 815 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Montréal, QC, Canada Phone (514) 398-8741 Email: [email protected] Word count: 6,137 Tables: 6 Figures: 2 Paper Accepted for Publication in Research in Transportation Economics, August 14, 2016. For citation please use: Flanagan, E., Lachapelle, U. & El-Geneidy, A. (accepted). Riding tandem: Does cycling infrastructure investment mirror gentrification and privilege in Portland, OR and Chicago, IL? Research in Transportation Economics. 1 Abstract Bicycles have the potential to provide an environmentally friendly, healthy, low cost, and enjoyable transportation option to people of all socio-demographic backgrounds. This research assesses the geographic distribution of cycling infrastructure with regard to community demographic characteristics to assess claims that cycling investment arrives in tandem with incoming populations of privilege or is targeted towards neighborhoods with existing socioeconomic wealth. Using census and municipal cycling infrastructure data in Chicago and Portland from 1990 to 2010, we create demographic and cycling infrastructure investment indices at the census tract level. -

May-June 2014

AMERICAN BICYCLIST URBAN REVIVAL BICI CULTURA IN CULTIVATING A THROUGH BIKING SANTA BARBARA BIKE CULTURE How cycling and Bringing cultures A women’s bike club culture connect to together through is changing the scene bring cities to life p. 12 bicycling p. 16 in the Big Easy p. 22 May - June 2014 WWW.BIKELEAGUE.ORG AMERICAN BICYCLIST CONTENT May - June 2014 THINK BIKE TRANSPORTATION CULTURE CLASH A challenge for bike advocates 10 BFA WORKSTAND 12 URBAN REVIVAL THROUGH BIKING How cycling and culture connect to bring cities to life PEDAL PROGRESS 16 RED TILES & SPOKES: BICI CULTURA IN SANTA BARBARA Bringing cultures together through bicycling WOMEN BIKE The monthly Bike Moves ride in Santa Barbara, Calif. 22 Photo by Christine Burgeois CULTIVATING A WOMEN BIKE CULTURE NOLA Women on Bikes is changing the IN EVERY ISSUE scene in the Big Easy 02 VIEWPOINT BIKES ALIVE IN TRANSYLVANIA How two women made cycling part of 24 03 INBOX Transy campus culture 04 COGS&GEARS 14 INFOGRAPHIC 28 QUICKSTOP AMERICAN BICYCLIST IS PRINTED WITH SOY INK ON 30% POST-CONSUMER RECYCLED PAPER CERTIFIED BY RAINFOREST ALLIANCE TO THE FOREST STEWARDSHIP COUNCIL™ STANDARDS. ON THE COVER: PHOTOS BY ROBIN GAUTHIER VIEWPOINT THE BEAUTY OF BIKE CULTURE Gaudy green bike lanes, shiny new bike the cops on bikes program that started sharing systems and the newest Dan- in 1993 and has more than 300 trained ish cycle track designs are all the rage as officers. A big step towards a BMX park U.S. communities strive to become more was taken the day I was there and more bike-friendly. -

AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities-2012

--`,`,`,``,`,``,`````,```,`,```,-`-`,,`,,`,`,,`--- Copyright American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Provided by IHS under license with AASHTO Licensee=Purdue University/5923082001 No reproduction or networking permitted without license from IHS Not for Resale, 06/14/2012 21:55:46 MDT --`,`,`,``,`,``,`````,```,`,```,-`-`,,`,,`,`,,`--- © 2012 by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Copyright American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Provided by IHS under license with AASHTO All rights reserved. DuplicationLicensee=Purdue is a violation University/5923082001 of applicable law. No reproduction or networking permitted without license from IHS Not for Resale, 06/14/2012 21:55:46 MDT American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials --`,`,`,``,`,``,`````,```,`,```,-`-`,,`,,`,`,,`--- 444 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 249 Washington, DC 20001 202-624-5800 phone 202-624-5806 fax www.transportation.org © 2012 by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. All rights reserved. Duplication is a violation of applicable law. Front cover photographs courtesy of Alaska DOT, Carole Reichardt (Iowa DOT), and the Alliance for Biking and Walking. Back cover photograph courtesy of Patricia Little. Publication Code: GBF-4 • ISBN: 978-1-56051-527-2 © 2012 by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Copyright American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Provided by IHS under license with AASHTO All rights reserved. DuplicationLicensee=Purdue is a violation University/5923082001 of applicable law. No reproduction or networking permitted without license from IHS Not for Resale, 06/14/2012 21:55:46 MDT Executive Committee 2011–2012 Officers President: Kirk Steudle, P.E., MICHIGAN Vice President: Michael P. Lewis, RHODE ISLAND Secretary/Treasurer: Carlos Braceras, UTAH Regional Representatives REGION I Beverley K. -

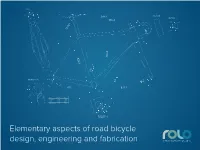

Elementary Aspects of Road Bicycle Design, Engineering

VIEW C 3 6 25 9,62 549,4 VIEW B-B SECTION - 376,4 B 16,08 5,50 8 149,7 72,82° 17,20 C B 562,4 522,9 A E E 10 5 27 150 SECTION A-A R8,20 74 46,3 R 10 9,46 32,50° 77,31° 411 574,1 A 141 147 153 brand 50teeth 53teeth Shimano 141mm 147mm 8,70 SRAM 141mm 147mm 25 Campagnolo 142mm 148mm R1,5 12 3,5° R7,6 6 5 R R 8,4 8,15 2 SECTION E-E SCALE 1 : 1 Elementary aspects of road bicycle design, engineering and fabrication © Motion Devices SA, 2015 © Motion Devices SA Page 1 Over the course of the last one hundred years, the design of the Contents diamond frame road racing bicycle has evolved surprisingly little. A quick look at frame building 2 Nonetheless, many riders complain about not feeling comfortable What has custom meant? 3 on their bicycles but do not always understand why that is the case. When is a monocoque a monocoque? 4 Few complain that their bicycles do not handle as they would wish, A quick background on carbon fiber 5 silently accepting that a new bicycle does not feel as intuitive as the Why a custom lay-up? 6 bicycles of their youth. They usually ascribe the difference to their It turns out that geometry is not as easy as it looks 7 rose colored backward looking glasses. The rule of thirds 8 Stack and reach explained 8 In fact, while correct bicycle design and engineering requires a The importance of being consistent 8 thorough understanding in order to produce a very high performing Top tube length 9 bicycle, it is not impossible to achieve. -

Secondary Research – Mountain Biking Market Profiles

Secondary Research – Mountain Biking Market Profiles Final Report Reproduction in whole or in part is not permitted without the express permission of Parks Canada PAR001-1020 Prepared for: Parks Canada March 2010 www.cra.ca 1-888-414-1336 Table of Contents Page Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 Sommaire .............................................................................................................................. 2 Overview ............................................................................................................................... 4 Origin .............................................................................................................................. 4 Mountain Biking Disciplines ............................................................................................. 4 Types of Mountain Bicycles .............................................................................................. 7 Emerging Trends .............................................................................................................. 7 Associations .......................................................................................................................... 8 International ...................................................................................................................