Pca Case Nº 2012-01 in the Matter Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newly Registered Companies

NewBiz NEWLY REGISTERED COMPANIES For the full list of transactions please go to www.btinvest.com.sg A selected listing comprising companies with issued capital between $200,000 and $5 million (March-April 2016) Accommodation & Food DEFENDEN SECURITY & Financial & Insurance KHAN FUNDS MANAGEMENT BATTERSBY CHOW STUDIO REIGN ASSETS PTE LTD SYSTEMATIC PARKING Service Activities CONSULTANT PTE LTD Activities ASIA PTE LTD PTE LTD 10, Genting Road PTE LTD 61, Kaki Bukit Avenue 1 2, Shenton Way 141, Middle Road, #04-07 #04-00, Singapore 349473 18, Kaki Bukit Road 3, #02-13 AGA FIVE SENSES PTE LTD #03-16 Shun Li Industrial Park XEQ PTE LTD #17-02 SGX Centre I GSM Building, Singapore 188976 Entrepreneur Business Centre 20, Limau Rise, Limau Villas Singapore 417943 10, Ubi Crescent, #06-94 Singapore 068804) REN ALLIANCE PTE LTD Singapore 415978 Singapore 465845 Ubi Techpark, Singapore 408564 BAYSWATER CAPITAL 10, Kaki Bukit Place ESN ASIA MANAGEMENT KINETIC VENTURE CAPITAL MANAGEMENT PTE LTD Eunos Techpark ULTIMATE DRIVE EUROSPORTS ASAM TREE PN PTE LTD PTE LTD ANTHILL CORPORATION PTE LTD 600, North Bridge Road Singapore 416188 PTE LTD 500, Old Choa Chu Kang Road 994, Bendemeer Road, #03-01B PTE LTD 442, Serangoon Road #12-02/03 Parkview Square 30, Teban Gardens Crescent #01-03, Singapore 698924 Central, Singapore 339943 46, Kim Yam Road, #02-21/12 #03-00/01, Singapore 218135 Singapore 188778 SINGAPORE ASASTA Singapore 608927 The Herencia, Singapore 239351 INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT BON FIDE (BUGIS) PTE LTD NACSSingapore PTE LTD MW CAPITAL MANAGEMENT BRIGHTER BRANDS PTE LTD PTE LTD VS&B CONTAINERS PTE LTD 17, Eden Grove, Bartley Rise 51, Ubi Avenue 1 ARES INVESTMENTS PTE LTD PTE LTD 10, Anson Road 152, Beach Road 141, Cecil Street, #08-03 Singapore 539072 #03-31 Paya Ubi Industrial Park 38, Martin Road, #08-04 205, Balestier Road, #02-03 #12-14 International Plaza #14-03 Gateway East Tung Ann Association Building Singapore 408933 Martin No. -

Urban Tropical Ecology in Singapore Biology / Environ 571A

URBAN TROPICAL ECOLOGY IN SINGAPORE BIOLOGY / ENVIRON 571A Course Description (from Duke University Bulletin) Experiential field oriented course in Singapore and Malaysia focusing on human ecology, tropical diversity, disturbed habitats, Asian extinctions, and resource management. Students spend approximately three weeks in Singapore/Malaysia during the spring semester. Additional course fees apply. Faculty: Dr. Dan Rittschof, Dr. Tom Schultz General Description Singapore is a fascinating combination of biophysical, human and institutional ecology, tropical diversity, disturbed habitats, invasive species and built environments. Within the boundaries of the city state/island of Singapore one can go from patches of primary rain forest to housing estates for 4.8 million plus residents, industrial complexes, and a port that processes between 800 and 1000 ships a day. Singapore's land area grew from 581.5 km2 (224.5 sq mi) in the 1960s to 704 km2 (271.8 sq mi) today, and may grow by another 100 km² (38.6 sq mi) by 2030. Singapore includes thousands of introduced species, including a multicultural assemblage of human inhabitants. Singapore should be in the Guinness Book of World Records for its increase in relative country size due to reclamation, and for the degree of governmental planning and control for the lives of its citizens. It is within this biological and social context that this experiential field oriented seminar will be conducted. Students will experience how this city state functions, and how it has worked to maintain and enhance the quality of life of its citizens while intentionally and unintentionally radically modifying its environment, in the midst of the extremely complicated geopolitical situation of Southeast Asia. -

Temasek Review 2017

Temasek Review 2017 Investor Institution Steward Investor Institution Steward Section Title orn scarcely a decade into Singapore’s independence, we had no blueprint except for the Singapore DNA of integrity and courage. We grew with a transforming Singapore, ventured abroad in an ascendant Asia, and tapped into emerging global trends. We constantly reinvent ourselves to remain relevant. Agility, Alignment and Accountability are our watchwords in the new world of disruptive technologies, uncertain geopolitics, and shifting economic powers. We treasure the solid foundation laid by pioneers before us, in and outside of Temasek. Our culture of ownership shapes our institution. Our people are the bedrock of our Temasek values. Our purpose and passion give us courage to embrace the future and its endless possibilities. Doing the right things today with tomorrow in mind, we strive for an ABC World – an Active Economy for jobs and opportunities; a Beautiful Society of peace and inclusion; and a Clean Earth as our common home. Forty ‑ three years on, we remain true to our DNA, our roots, our core – as an active Investor, a forward looking Institution, and a trusted Steward. Contents The Temasek Charter 4 Ten ‑ year Performance Overview 6 Portfolio Highlights 8 From Our Chairman 10 The DNA of Temasek 14 Ins & Outs of Temasek 16 Investor 19 Value since Inception 20 Total Shareholder Return 21 An Active Investor 22 Investing for Generations 24 T ‑ GEM Simulations 28 Managing Risk 32 Institution 39 Our MERITT Values 40 A Forward Looking Institution -

Our Journey Has Just Begun

Temasek Review 2014 Review Temasek Our journey has just begun Temasek Review 2014 Our journey has just begun Cover: Sherlyn Lim on an outing with her sons, Amos and Dean, on Sentosa Island, Singapore. Our journey has just begun The world is fast changing around us. Populations urbanise, and life expectancies continue to rise. We are entering a new digital age – machines are increasingly smarter, and people ever more connected. Change brings unprecedented challenges – competing demands for finite resources, safe food and clean water; health care for an ageing population. Challenges spawn novel solutions – personalised medicine, digital currencies, and more. As investor, institution and steward, Temasek is ready to embrace the future with all that it brings. With each step, we forge a new path. At 40, our journey has just begun. TR2014_version_28 12.00pm 26 June 2014 Contents The Temasek Charter 4 Ten-year Performance Overview 6 Portfolio Highlights 8 From Our Chairman 10 Investor 16 Value since Inception 18 Total Shareholder Return 19 Investment Philosophy 20 Year in Review 24 Looking Ahead 26 Managing Risk 28 Institution 34 Our MERITT Values 36 Public Markers 37 Our Temasek Heartbeat 38 Financing Framework 42 Wealth Added 44 Remuneration Philosophy 45 Seeding Future Enterprises 48 Board of Directors 50 Senior Management 57 2 Temasek Review 2014 Contents Steward 60 Trusted Steward 62 Fostering Stewardship and Governance 67 Social Endowments & Community Engagement 68 Touching Lives 72 From Ideas to Solutions 74 Engaging Friends 75 Temasek International Panel 76 Temasek Advisory Panel 77 Group Financial Summary 78 Statement by Auditors 80 Statement by Directors 81 Group Financial Highlights 82 Group Income Statements 84 Group Balance Sheets 85 Group Cash Flow Statements 86 Group Statements of Changes in Equity 87 Major Investments 88 Contact Information 98 Temasek Portfolio at Inception 100 Explore Temasek Review 2014 at www.temasekreview.com.sg or scan the QR code 3 TR2014_version_28 12.00pm 26 June 2014 A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Roy-Ngerngs-Closing-Statement-In

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE Suit No. 569 of 2014 Between LEE HSIEN LOONG (NRIC NO. S0016646D) …Plaintiff And ROY NGERNG YI LING (NRIC NO. S8113784F) …Defendant DEFENDANT’S CLOSING STATEMENT Solicitors for the Plaintiff Defendant in-Person Mr Davinder Singh S.C. Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Ms Tan Liyun Samantha Ms Cheng Xingyang Angela Mr Imran Rahim Roy Ngerng Yi Ling Drew & Napier LLC Block 354C 10 Collyer Quay #10-01 Admiralty Drive Ocean Financial Centre #14-240 Singapore 049315 Singapore 753354 Tel: 6535 0733 Tel: 9101 2685 Fax: 6535 7149 File Ref: DS/318368 Dated this 31st day of August 2015 2 DEFENDANT’S CLOSING STATEMENT A. Introduction 1. I am Roy. I am 34 this year. Little did I imagine that one day, I would be sued by the prime minister of Singapore. Throughout my whole life, I have tried my very best to live an honest life and to be true to myself and what I believe in. 2. When I was in primary school, I would reach out to my Malay and Indian classmates to make friends with them because I did not want them to feel any different. This continued when I went to secondary school and during my work life. Some of my closest friends have been Singaporeans from the different races. From young, I understand how it feels to be different and I did not want others to feel any differently about who they are. 3. But it is not an easy path in life, for life is about learning and growing as a person, and sometimes life throws challenges at you, and you have to learn to overcome it to become a stronger person. -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

Board of Directors

13 SINGAPORE TELECOMMUNICATIONS LIMITED Board of Directors SIMON ISRAEL • Non-executive and non-independent Director • Member, Optus Advisory Committee • Chairman, Singtel Board • Date of Appointment: Director on 4 Jul • Chairman, Finance and Investment Committee 2003 and Chairman on 29 Jul 2011 • Member, Corporate Governance and • Last Re-elected: 26 Jul 2013 Nominations Committee • Number of directorships in listed • Member, Executive Resource and companies (including Singtel): 4 Compensation Committee Mr Simon Israel, 63, is the Chairman of Singapore Post Limited and a Director of CapitaLand Limited, Fonterra Co-operative Group Limited and Stewardship Asia Centre Pte. Ltd. He is also a member of the Governing Board of Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and Westpac’s Asia Advisory Board. Simon is a former Chairman of Asia Pacifi c Breweries Limited. Simon was an Executive Director and President of Temasek Holdings (Private) Limited before retiring on 1 July 2011. Prior to that, he was Chairman, Asia Pacifi c of the Danone Group. Simon also held various positions in Sara Lee Corporation before becoming President (Household & Personal Care), Asia Pacifi c. Simon was conferred Knight in the Legion of Honour by the French government in 2007 and awarded the Public Service Medal at the Singapore National Day Awards 2011. He holds a Diploma in Business Studies from The University of the South Pacifi c. CHUA SOCK KOONG • Executive and non-independent Director • Last Re-elected: 21 Jul 2015 • Member, Optus Advisory Committee • Number of directorships in listed • Date of Appointment: Director on 12 Oct companies (including Singtel): 2 2006 and Group Chief Executive Officer (CEO) on 1 Apr 2007 Ms Chua Sock Koong, 58, was appointed Group CEO on 1 April 2007. -

ATTACHMENT 1 Ihc Hrr~Imblc Kiikn R Lwiiicli Llniiud States Tradc Kcpresentiilivc Rku .\Rnhnnsndor Lucllick

ATTACHMENT 1 Ihc Hrr~imblc Kiikn R LwIIicli Llniiud States Tradc Kcpresentiilivc rku .\rnhnnsndor Lucllick: Ihe Singapore Government is c;omnlined IO he privati7ation of SingTcl and ST Telemedia and In the ob.jectirr reducing iis existing slakes in lhcnc companies lo zcm. subject IO hesmc of capiml rnarkeu and the intcrens afolher shareholden. The Singapom Ciuvermnent will thermflci only hold shares it) hcse conlpmies us part of its pflfolio investments. For Sing Iel. the privariwucn procerr Iregm in 1993 with he listing of SingTcl on the Singapore Stack iFuchange Since then. the Singapore Govcmmcm hac progressively reduced its nake In Sing 'lei 3nd cunently hrilds 67.56% of ih shares. SingTcl ha< also been listcd on the .4uslralian Stock Fxchaiee MCC Ssprcmber 2001 The Singapore Guvenimcnl will establish a plan to divM ia majority hein Sing'Iel and ST Telemedia. Thu Singopon- Govcnuneiit undcrhunds ilic Unitcd States' inrnen in seeing such iiirezinicnl cumpleted ;~5soon feasible. I he Singapom (;ovemrnenl cacrci.ses no cunlrol over the commercial policy of Sing'rel and ST relelrldia and thr Singnport Government does nnt have veto rightsover ihe key decisions of liirse mnpanles bg way 01 a 'golden share' Neilher SingTrl nor ST Telemcdia receives my subhid? from die Singapcire imverlirnznt. Dolh SingTel aid SI' '1-eiemcdnBTC hlly subject Io Ihe irdepeudenl regukdlov ovnsiglu and sulhririiy or Ihe info-wminunicalions Development Aurhority of Singapore (IDA). wiich is ernprwurcd under he Info-conimunicutions Develupmcnt Aulhority ofsingapore Act to ensure lh31 rhcg 40 1101 ciigdge in :iiiti-cwnpetilive bchavior. Sinccrcly. ATTACHMENT 2 Temasek Holdings is an investment holding company based in Singapore. -

Technocracy in Economic Policy-Making in Malaysia

Technocracy in Economic Policy-Making in Malaysia Khadijah Md Khalid* and Mahani Zainal Abidin** This article looks at the role of the technocracy in economic policy-making in Malay- sia. The analysis was conducted across two phases, namely the period before and after the 1997/98 economic and financial crises, and during the premiership of four prime ministers namely Tun Razak, Dr Mahathir, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, and Najib Razak. It is claimed that the technocrats played an important role in helping the political leadership achieve their objectives. The article traces the changing fortunes of the technocracy from the 1970s to the present. Under the premiership of Tun Razak, technocrats played an important role in ensuring the success of his programs. However, under Dr Mahathir, the technocrats sometimes took a back seat because their approach was not in line with some of his more visionary ventures and his unconventional approach particularly in managing the 1997/98 financial crisis. Under the leadership of both Abdullah Ahmad Badawi and Najib Razak, the technocrats regain their previous position of prominence in policy-making. In conclusion, the technocracy with their expert knowledge, have served as an important force in Malaysia. Although their approach is based on economic rationality, their skills have been effectively negotiated with the demands of the political leadership, because of which Malaysia is able to maintain both economic growth and political stability. Keywords: technocracy, the New Economic Policy (NEP), Tun Abdul Razak, Dr Mahathir Mohamad, National Economic Action Council (NEAC), government-linked companies (GLCs), Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Najib Tun Razak Introduction Malaysia is a resource rich economy that had achieved high economic growth since early 1970s until the outbreak of the Asian crisis in 1998. -

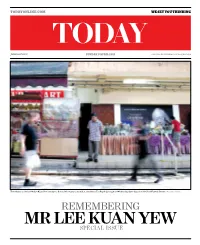

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did.