Interalia, a Peer-Edited Scholarly Journal for Queer Theory, Is Open to Submissions from a Wide Range of Fields, Written in Polish, English Or Spanish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P Arallel Lives Parallel L I V

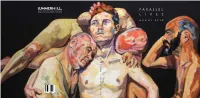

PARALLEL PARALLEL LIVES PARALLEL LIVES ANGUS REID PARALLEL LIVES • ANGUS REID LIVES • PARALLEL parallel lives Angus Reid combines painting and drawing, film-making and historical research to make this ground-breaking vision of gay men in Scotland, past and present. The images portray same-sex love and tenderness. Why does this love inspire fear? Why have images like these never been shown in public in Scotland? The research goes deep into secret archives to find the story of Harry Whyte, Scotland’s forgotten advocate of gay liberation who stood up to Stalin when it mattered. Whyte’s protest is parallel to that of Tomasz Kitliński in contemporary Poland; Reid works in solidarity with Kitliński, and the Polish LBGT community. Parallel Lives is a potent mix of art and activism, whose message reaches beyond the gallery and has become ever more urgent over the past months. Using the tools of lockdown Reid kick-starts conversations about The Male Nude, about Being Painted, about Harry Whyte, about Stalin and the Homosexuals, and to make a stand against homophobia he asks Peter Tatchell for a master-class in LGBT activism. Click on the titles to launch the films. Those films, this catalogue and the exhibition itself aim to start conversations within the LGBT community and in society at large about art, about tolerance, about love, and about activism. Curated by Andrew Brown and Robert McDowell 3 4 parallel lives angus reid I am not alone but I feel alone do I obey the uncontrollable beating of my heart I feel alone but I am not alone I have -

Pride, Politics and Protest a Revolutionary Guide to LGBT+ Liberation

PRIDE, POLITICS AND PROTEST A Revolutionary Guide to LGBT+ Liberation A Socialist Worker pamphlet by Laura Miles, Isabel Ringrose & Tomáš Tengely-Evans About the authors Laura Miles has been a revolutionary socialist and member of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) since 1975. She was the first trans person elected to the UCU universities and colleges union’s national executive committee, 2009‑2015. Her book, Transgender Resistance: Socialism and the Fight for Trans Liberation, was published by Bookmarks in 2020. Isabel Ringrose is a journalist on Socialist Worker and member of the SWP in east London Tomáš Tengely-Evans has worked as a journalist for Socialist Worker and is a member of the party in north London. Pride, Politics and Protest: A Revolutionary Guide to LGBT+ Liberation 2nd edition by Laura Miles, Isabel Ringrose and Tomáš Tengely-Evans Published February 2021. © Socialist Worker PO Box 74955, London E16 9EJ ISBN 978 1 914143 14 4 Cover image by Guy Smallman Pride Politics and Protest 1 Introduction HE HISTORY of socialist struggles and socialist movements is also a history Tof fighting oppression. Creating a socialist society must also involve creating the conditions for ending oppression, including the oppression of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT+) people. Building a socialist world, run by working class people from the bottom up, requires winning masses of people to a vision of a new sort of society. It’s one where racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia are recognised for the cruel, pernicious and divisive ideas that they are. This is no easy task. Many people are torn between hopes for a better world—and a feeling that the rich and powerful who run the capitalist system are too strong to get rid of. -

Third Year of the Feminist Fund Dears

Our roots are growing stronger! Third year of the Feminist Fund Dears, FemFund is 3 years old already! We feel that after three years we are standing firmly on two legs: the femi- After two intense and fairly crazy nist community that uses the Fund’s years, 2020 was a year of rooting and money keeps on growing regularly, building strong foundations for the and there are also more and more mature and stable organization that persons who support the Fund FemFund wants to be. We used the with monthly donations. We are time of the pandemic to care for rela- an organization that specializes in tions within the team, strengthen the providing grants and feminist philan- organization’s security, order our pro- thropy. We reach groups and organi- cedures and formalities, and to talk zations from all over Poland, from about our vision of FemFund and how cities, towns, and villages; within the We invite you to read the summary to strengthen the feminist movement feminist movement, we support the of the year 2020 in FemFund! in Poland strategically and in the long voices of minorities, the excluded, run. and the marginalized. The persons Magda, Justyna, Gosia, who co-create this movement daily Marta and Mona still decide whom to support. Bigger and wiser FemFund! We started 2020 as a stronger team, from Ulex Project. It was a much about our key values, about the cur- joined by Mona Szychowiak and needed conversation, thanks to which rent political context, about the needs Gosia Leszko . A while later, we we were able to critically look at our of our community and its internal started a regular cooperation with practices of overworking and (not) diversity. -

Tuesday Karu to Be Interim Leader?

ITAK squabbling over National List pick TUESDAY BY SULOCHANA RAMIAH MOHAN 11 august 2020 LATEST EDITION VOL: 09/206 PRICE : Rs 30.00 The Illankai Thamizh Arasu Kachchi (ITAK), the main constituent party of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), is in a dilemma over who gets its only National List slot because ITAK Leader Mavai In Sports Senathirajah is in disagreement over giving it to a young TNA Member, Kalayarasan Thavarasa. Defenders thrash Senathirajah, who contested from the Jaffna District and Thavarasa, a former Eastern Provincial Super Sun 4-1 Councillor who contested from the Ampara District, were both defeated at the Parliamentary Election Defenders FC capitalised on shocking based on the number of preferential votes they errors by Super Sun SC to register a received. However, ITAK’s and TNA policy dictates comfortable 4-1 victory in their first that if a Party or Alliance Leader is defeated at a... Group ‘C’ match of the Inaugural FFSL President’s Cup 2020 worked off Story Continued on PAGE 2 at an empty Sugathadasa A16 Ranil Steps Down As UNP Leader Karu to be interim Leader? BY NABIYA VAFFOOR AND he added. The UNP General decision regarding the UPATISSA PERERA Secretary went on to state that leadership cannot be taken. although Media reports said According to the source, the UNP Leader and former that senior UNP members UNP Leader had asked Prime Minister Ranil including himself, Ravi Karunanayake, Kariyawasam Wickremesinghe has decided Karunanayake, Daya Gamage, and Abeywardena to discuss to step down as UNP Leader Vajira Abeywardena and Navin and reach a decision regarding after being in the position for Dissanayake were pursuing the Party leadership and 26 consecutive years, UNP the UNP Leader post, inform him of that decision General Secretary Akila Viraj Dissanayake had withdrawn tomorrow morning. -

Publish Date: 2020-09-10

THEORY / PRACTICE & “HumanNEWS power is its own end”—Karl Marx LETTERSVol. 65 No. 5 September-October 2020 Yemen: A voice that Amid election battles, masses must be heard The intense suffering of Yemen’s people contin- ues. The country is torn by a regional imperialist demand no return to normal war between the Saudi Arabia-sponsored govern- by Terry Moon peace, an end to racism and police killings, and a ment and the Iran-sponsored Houthi rebels, with refusal to return to the way things have always been. There is rage in America—rage at the choices both relying on various unprincipled alliances; Now there’s rage and fear about the com- the Trump administration has forced on people by militia allied with the United Arab Emirates; and ing election. Politicians talk about “the peo- his purposeful bungling of the coronavirus pandem- ISIS and al-Qaeda factions. The result amounts to ple,” as if they speak for them. But Donald ic, rage at his racism, sexism, disdain for people with genocide. Trump and his enablers dread “the people” disabilities; and anger at his attempts to destroy This is a counter- as he orders the police and Federal EDITORIAL revolution against the thugs to beat, teargas, jail and lie 2011 revolution—for about their victims. the imperialist rulers, it was a conscious decision to This dread of “the people”—which is choose a path of repression, however extreme, over fear of revolt, of revolution—has never human freedom. been more obvious than in the blatant More than 100,000 people, mostly civil- and often frighteningly effective efforts ians, have died as a direct result of the fight- to silence and disenfranchise voters and ing. -

LGBTQI+ Communities: a Reporters' Guide

LGBTQI+ COMMUNITIES A REPORTERS’ GUIDE IMPRESSUM: LGBTQI+ COMMUNITIES, A REPORTERS’ GUIDE Produced by: European Journalism Centre (www.ejc.net) Author: Lisa Anne Essex Editor: Josh LaPorte Contributors: Anastasia Lykholat, Matthew Schaaf, Peter Verweij, Tymur Levchuk, Claire Gheerbrant Production Co-ordinator: Marjan Tillmans Photographs have been kindly provided by: Hugo Greenhalgh & Lin Taylor (Thomson Reuters Foundation), Bart Staszewski (LGBT-Free Zones Project), Rémy Bonny (Forbidden Colours), Agata Grzybowska & Karol Grygoruk (RATS Agency), Aleksandr Malytsky, Carl Collison, Gender Z, Victor Vysochin Royalty Free Images: Shutterstock.com & Unsplash.com Design and Layout: SlickStudio, South Africa © The text of the handbook is licensed under a Create Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike licence. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD: A focus on Central and Eastern Europe 5 ISSUES 49 INTRODUCTION 7 Science and Medicine 51 DIVERSITY AND NEWS 9 Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) 55 Acting Ethically 11 Homophobia as Political Strategy 59 Audience Appeal: Finding and Writing Stories 13 Religion 64 Sourcing and Interviewing 19 International Obligations vs Local Law 69 Safety and Security 23 Young People 75 Verification and Data 26 Living an LGBT Life 77 Press Freedom 33 Advocacy and Change 81 WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW... 37 RESOURCES 85 Terminology 39 Myth vs Reality 45 Cover Photo: Karol Grygoruk / RATS Agency 3 Photos: Bart Staszewski / LGBT-Free Zones Project FOREWORD: A FOCUS ON CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE LGBTI communities in Central and Eastern European countries continue their struggle As an activist, I sometimes give myself up to the feeling that “nothing will change’’, but for rights and recognition, as you will read in this guide.