Fictional Representations of Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Computer Expert Predicts Future of Networking Farber Says That the Proposed Tufts Upgrade Not Extensive Enough He Said

~ ~ THETUFTS DAILY Volume XXXVIII, Number 55 [Where You Read It First Thursdav, April 22,1999 I Computer expert predicts future of networking Farber says that the proposed Tufts upgrade not extensive enough he said. Though he supported the proposed upgrade, he expressed by JEREMY WANGIVERSON trust lawsuit and is nationally bedroom or study. point, but other factors might im- doubts as to whether it was exten- Daily Editorial Board known for his “Interesting People Farber also spoke about the pede their development. sive enough. After 40 years of watching the mailing list,”adaily e-mail which potential dangers of powerful “Technology is easy; society “It’s being advertised as amajor field develop and grow, Univer- updates 25,000 readers on news telecommunications devices. isrough,”he explained,citingtaxes, leap,”he said. “It’sanice incremen- sity of Pennsylvania professor and on the technology front. Currently, anyone can be easily culture, and law as the major tal step in capability,” he added. computer science pioneer David Wiredmagazine wrotethat“his pinpointed every time they use a hurdles inhibiting technological TCCS Telecommunications Di- Farber has a unique perspective technical chops and the public credit card, ATM, or even a Tufts advancement. rector Lesley Tolman and associ- when it comes to predicting the spirit’’ make Farber the “Paul Re- ID. This ability to track people, Farber also discussed Internet ate Wilson Dillaway explained the future of the Internet. vere of the Digital Revolution.” he said, will be enhanced with 2, which Tufts is proposing as a advantages of the faster network. Farber spoke to nearly 50 Farber spoke for an hour before every improvement in technol- long-awaited upgrade to campus “Students will be able to use people, primarily faculty and staff, answering questions, centering ogy * network technology. -

Prominent Political Consultant and Former U.S. Senator Serve As Sanders Scholars

Headlines Prominent political consultant and former U.S. senator serve as Sanders Scholars wo renowned individuals joined the promote the administration’s agenda. He was later appointed U.S. ambassador TUniversity of Georgia School of Law fac- Currently, Begala serves as Research to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. ulty as Carl E. Sanders Political Leadership Professor of Government at Georgetown Among the numerous recognitions he Scholars this academic year – Paul E. Begala, University and is also a political analyst and has received are: the Federal Bureau of political contributor on CNN’s “The commentator for CNN, where he previously Investigation’s highest civilian honor, the Situation Room” and former counselor to co-hosted “Crossfire.” Jefferson Cup; selection as the Most Effective President Bill Clinton, and former U.S. Sen. While on campus, Begala also delivered Legislator by the Southern Governors’ Wyche Fowler Jr. a speech to the university community titled Association; and the Central Intelligence During the fall semester, Begala taught “Politics 2008: Serious Business or Show Agency “Seal” medallion for dedicated ser- Law and Policy, Politics and the Press, while Business for Ugly People?” vice. Fowler is teaching a course on the U.S. Currently, Fowler is Named for Georgia’s 74th governor and Congress and the Constitution this spring. engaged in an interna- 1948 Georgia Law alumnus, Carl E. Sanders, As a former top-rank- tional business and law the Sanders Chair in Political Leadership was ing White House official, practice and serves as created to give law students the opportunity political consultant, cor- chair of the board of the to learn from individuals who have distin- porate communications Middle East Institute, a guished themselves in politics or other forms strategist and university nonprofit research foun- of public service. -

23Rd Annual Legislative Forum October 4, 2018 Legislative Forum 2018

GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS RIGHT TIME. RIGHT PLACE. RIGHT SOLUTION. 23RD ANNUAL LEGISLATIVE FORUM OCTOBER 4, 2018 LEGISLATIVE FORUM 2018 Maine could make national headlines this November because of the number of key races on the ballot this year. With important seats up for grabs and two political parties looking to score “big wins” in our state, the only thing we can predict about our political forecast is that it is unpredictable. • Who will be Maine’s next Governor? • Which party will take control of the State Legislature? • Will incumbents prevail in Maine’s first and second Congressional districts? • Who will win the race for U.S. Senate, and will the result impact the balance of power in Washington? With so much up in the air here in Maine and a stagnant climate looming over Washington, our Legislative Forum’s key note speaker, CNN commentator Paul Begala, will offer his unique perspective and insight on today’s political landscape. He will discuss why Maine’s races will be closely watched and talk about the impact the 2018 midterm elections will have on our country and state. Begala will also offer his thoughts on the biggest issues facing Congress and how the election will impact Washington’s agenda. We’ll also bring to the stage radio power duo Ken and Matt from WGAN Newsradio’s Ken & Matt Show to share their political humor and insights with our Forum guests. Through their comedic banter, they will give “their take” on today’s top policy issues and the candidates running for office. And to close out the day, Maine Credit Union League President/CEO Todd Mason will interview a Special Guest to talk about why credit union advocacy and electing pro-credit union candidates matter. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

April 2020 Delray Beach, Florida

PALM GREENS PULSE APRIL 2020 DELRAY BEACH, FLORIDA YOU ARE HERE! 2 Palm Greens Pulse Palm Greens Pulse IN THIS ISSUE 561-499-5444 PAGE NO. ARTICLES 3 Condo 1 & Condo 2 4 From the Editor & Recreation Board 5 Men’s Club & Women’s club 6 Entertainment Committee & President/Treasurer V.P./Managing Editor Andrea Goldstein Mel Clapman Tennis Committee 7 Alliance of Delray & Tennis Social Club 8 Four Seasons & AUM Article Gift Card Scams 9 The Health Room & Time Saving Tips Production Manager Advertising Manager/Secretary 10 Tennis Pro & POI Beth Villanova Rhoda Misikoff Officers AFTER PAGE 10 Andrea Goldstein, President Mel Clapman, Vice-President Coronavirus Friday Night Movie Directors Gloria Kostrzecha Cele Fagan Beth Villanova Nobody asked me Sharon Mossovitz Rachel Rodgers Rhoda Bermon We Care Channel 63 Mel Clapman DISCLAIMER The Unit Owners Association of Palm Greens (UOAPG) and its publication, The Palm Greens Pulse, are not responsible for the services, products and/or claims made by our adver- tisers. We welcome articles of interest pertaining to Palm Greens as well as black and white photos. All submissions are subject to approval by the editor. Please address all correspondence to: The Palm Greens Pulse – 5801 Via Delray – Delray Beach FL 33484. We Office Hours request all articles be sent to The Pulse via email – Monday-Friday [email protected]. 9:00 AM - 5:30 PM Saturday 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM Appointments Suggested NW Corner of Hagen Ranch Rd. & Flavor Pict Rd. Whitworth Farms Office | 561.736.3880 12393 Hagen Ranch, Suite 301 Toll Free | 1.877.736.3880 Boynton Beach, FL 33437 Fax | 561.737.3035 visit us at www.sandctravel.com Email | [email protected] April 2020 3 CONDO 2 CONDO 1 by Allen Tirone We are approaching the time when most seasonal unit owners prepare to leave their units unoccupied Hard to believe but it’s already that time of year for extended periods of time as they return to their when our snowbirds return to their summer homes. -

CNN Pundit Regales Scientific Assembly with Tales of Clinton, Bush, and Obama

EMERGENCY MEDICINE NEWS Exclusively for EMNow’s ACEP Scientific Assembly Edition: October 2009 CNN Pundit Regales Scientific Assembly with Tales of Clinton, Bush, and Obama By Lisa Hoffman thought of the book, he said, “It always helps when people misun- f you close your eyes when Paul Begala does his Bill Clinton derestimate me.” Iimpersonation, you might swear the former president was Barack Obama is another story, in the room. It’s an uncanny display that nails the Arkansas however, Mr. Begala said, and even drawl, the deliberate gestures, and the sincere facial expres- those who oppose him don’t deny sions. That characterization was learned at the knee, as it he is brilliant and politically adept. were, after Mr. Begala spent years as a key player in Clinton’s He has learned from others’ past inner circle. mistakes, and “it’s because we Mr. Begala proudly admits he’s a Democrat, and failed in ’93 and ‘94 that he’s likely Mr. Paul Begala although he now makes his living as a CNN political ana- to succeed. He’s put his whole lyst, no one would ever accuse him of representing any- political capital behind health care.” thing less than a liberal perspective. And he was there the Mr. Begala said the most remarkable thing about President first time around when health care reform ultimately went Obama is what he called his American exceptionalism. The down in flames in the early 1990s, its defeat in large part President himself said his story is unimaginable in any other due to his boss’s inflexibility, said Mr. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

Download Archetypes of Wisdom an Introduction to Philosophy 7Th

ARCHETYPES OF WISDOM AN INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 7TH EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Douglas J Soccio | --- | --- | --- | 9780495603825 | --- | --- Archetypes of Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy This specific ISBN edition is currently not available. How Ernest Dichter, an acolyte of Sigmund Freud, revolutionised marketing". Magician Alchemist Engineer Innovator Scientist. Appropriation in the arts. Pachuco Black knight. Main article: Archetypal literary criticism. Philosophy Required for College Course. The CD worded perfectly as it had never been taken out of its sleeve. Columbina Mammy stereotype. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Namespaces Article Talk. Buy It Now. The concept of psychological archetypes was advanced by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jungc. The Stoic Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. The Sixth Edition represents a careful revision, with all changes made by Soccio to enhance and refresh the book's reader-praised search-for-wisdom motif. Drama Film Literary Theatre. Main article: Theory of Forms. The origins of the archetypal hypothesis date as far back as Plato. Some philosophers also translate the archetype as "essence" in order to avoid confusion with respect to Plato's conceptualization of Forms. This is because readers can relate to and identify with the characters and the situation, both socially and culturally. Cultural appropriation Appropriation in sociology Articulation in sociology Trope literature Academic dishonesty Authorship Genius Intellectual property Recontextualisation. Most relevant reviews. Dragon Lady Femme fatale Tsundere. Extremely reader friendly, this test examines philosophies and philosophers while using numerous pedagogical illustrations, special features, and an approachable page design to make this oftentimes daunting subject more engaging. Index of Margin Quotes. Biology Of The Archetype. Wikimedia Commons. -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

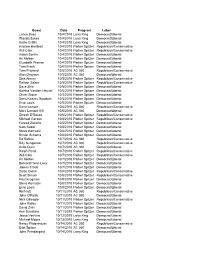

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Wanda Sykes 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Kathy Griffin 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Andrew Breitbart 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Will Cain 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Aaron Sorkin 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ari Melber 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Elizabeth Warren 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Frank 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Prichard 10/5/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Alan Grayson 10/5/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dick Armey 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Reihan Salam 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Dave Zirin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Katrina Vanden Heuvel 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Oliver Stone 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Doris Kearns Goodwin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Errol Louis 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Dana Loesch 10/6/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Marc Lamont Hill 10/6/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dinesh D'Souza 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Michael Gerson 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Fareed Zakaria 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Sam Seder 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Steve Kornacki 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Simon Schama 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ed Rollins 10/7/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Billy Nungesser 10/7/2010