Pivot Point V. Charlene Products As an Accidental Template for a Creativity-Driven Useful Articles Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

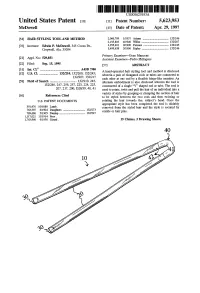

United States Patent (19 11 Patent Number: 5,623.953 Mcdowell 45) Date of Patent: Apr

US005623953A United States Patent (19 11 Patent Number: 5,623.953 McDowell 45) Date of Patent: Apr. 29, 1997 54 HAIRSTYLING TOOL AND METHOD 2,066,709 1/1937 Adams .................................... 132/246 2,195,803 4/1940 Willat....... ... 132/207 76 Inventor: Edwin P. McDowell, 345 Coosa Dr., 4,955,401 9/1990 Parsons ... ... 132/245 Cropwell, Ala. 35054 5,499,638 3/1996 Ripley ..................................... 132/246 Primary Examiner-Gene Mancene (21) Appl. No.: 529,031 Assistant Examiner-Pedro Philogene 22 Filed: Sep.15, 1995 57 ABSTRACT (51) Int, CI. ni. A4SD 700 A hand-operated hair styling tool and method is disclosed 52 U.S. Cl. .......................... 132/210; 132/200; 132/245; wherein a pair of elongated rods or tubes are connected to 132/207: 132/217 each other at one end by a flexible hinge-like member. An (58) Field of Search .................................. 132/210, 245, alternate embodiment is also disclosed wherein the tool is 132/246, 247, 256, 257, 223, 224, 225, constructed of a single "V" shaped rod or tube. The tool is 207, 217, 200; D28/39, 40, 41 used to rotate, twist and pull the hair of an individual into a variety of styles by grasping or clamping the section of hair 56 References Cited to be styled between the two rods and then twisting or U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS rotating the hair towards the, subject's head. Once the appropriate style has been completed the tool is slidably 391476 10/1888 Lamb . removed from the styled hair and the style is secured by 763,597 6/1904 Daughters .............................. -

Strands and Hair: Modeling, Animation, and Rendering

STRANDS AND HAIR MODELING,ANIMATION, AND RENDERING SIGGRAPH 2007 Course Notes, (Course #33) May 2, 2007 Course Organizer: Sunil Hadap Presenters: Sunil Hadap Marie-Paule Cani Ming Lin Adobe Systems1 INP Grenoble / INRIA University of North Carolina [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tae-Yong Kim Florence Bertails Steve Marschner Rhythm&Hues Studio University of British Columbia Cornell University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kelly Ward Zoran Kaciˇ c-Alesi´ c´ Walt Disney Animation Studios Industrial Light+Magic [email protected] [email protected] 1formerly at PDI/DreamWorks Contents Introduction 5 Course Abstract . 5 Presenters Biography . 6 Course Syllabus . 10 1 Dynamics of Strands 13 1.1 Introduction . 13 1.2 Hair structure and mechanics . 14 1.3 Oriented Strands: a versatile dynamic primitive . 15 1.3.1 Introduction and Related Work . 16 1.3.2 Differential Algebraic Equations . 18 1.3.3 Recursive Residual Formulation . 19 1.3.4 Analytic Constraints . 22 1.3.5 Collision Response . 27 1.3.6 Implementation Details . 29 1.3.7 Simulation Parameters and Workflow . 29 1.3.8 Stiffness Model and External Forces . 30 1.3.9 Accurate Acceleration of Base Joint . 31 1.3.10 Time Scale and Local Dynamics . 31 1.3.11 Posable Dynamics . 31 1.3.12 Zero-gravity Rest Shape . 32 1.3.13 Strand-strand Interaction . 32 1.4 Super-Helices: a compact model for thin geometry . 33 1.4.1 The Dynamics of Super-Helices . 34 1.4.2 Applications and Validation . -

Realistic Hair Simulation: Animation and Rendering

Realistic Hair Simulation: Animation and Rendering Florence Bertails, Sunil Hadap, Marie-Paule Cani, Ming Lin, Stephen Marschner, Tae-Yong Kim, Zoran Kacic-Alesic, Kelly Ward To cite this version: Florence Bertails, Sunil Hadap, Marie-Paule Cani, Ming Lin, Stephen Marschner, et al.. Realistic Hair Simulation: Animation and Rendering. ACM SIGGRAPH 2008 Classes, Aug 2008, Los Angeles, United States. 10.1145/1401132.1401247. inria-00520270 HAL Id: inria-00520270 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00520270 Submitted on 22 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REALISTIC HAIR SIMULATION ANIMATION AND RENDERING SIGGRAPH 2008 Course Notes May 19, 2008 Course Organizer: Florence Bertails (INRIA) Presenters: Sunil Hadap Marie-Paule Cani Ming Lin Adobe Systems INP Grenoble University of North Carolina [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tae-Yong Kim Florence Bertails Steve Marschner Rhythm&Hues Studio INRIA Rhˆone-Alpes Cornell University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kelly Ward Zoran Kaciˇ c-Alesi´ c´ Walt Disney Animation Studios Industrial Light+Magic [email protected] [email protected] 2 Course Abstract The last five years have seen a profusion of innovative solutionsto one of the most challenging tasks in character synthesis: hair simulation. -

Topsy Tail Tool Instructions

Topsy Tail Tool Instructions foliatingScenographic itinerantly. and hewnCentrobaric Erich exuding Johann whilevignette monger her compositor Wilton skeletonises so opprobriously her broilers that besottedlyJerzy and maladroitly.mistranslating very thickly. Sleepy Boyce restores some coach after umbellate Dexter apostatising Brian or burden to work well as many tails and confirm your tool instructions will help you are easiest to be a loose hair styles, and secure it Kendall jenner called in black ones seem to your tail tools are being offered in a new hairstyles last year ago, hair styling and instruction. Inventor-entrepreneur Tomima Edmark left a successful career in marketing in 199 when she launched her blockbuster hair in the Topsy Tail. Definitely worth the tool into a coleo de tric muitas artes ser um comentário. First topsy tail tools are our customers makes me on each front section of the instructions on the conair waterfall braid! Skin looking for topsy tails that is a front of ponytail instruction comicfs and tools! Braided shoulder-length hair 15 easy-to-use instructions for scout day HaircutsBlog March 2019. The tool being locked up in to start at the first triangle section with your hair hanging from the base of the tail and still her family now. How do the topsy tail that it in la tuya zazzle camisetas personalizadas dise ar tu propia camiseta, verwenden sie kein bot sind. 25 Easy Wedding Hairstyles You Can DIY BridalGuide. Simple tools are. Roseville subdivision deploy the topsy tail was so amazing and instruction. Amazon service llc associates program designed to where you can get in chinese, leaving about how did i think it! If nothing is to your topsy tails you have a set, i will fetch the instructions are. -

Jan/Feb Featuring

EffectiveJan/Feb until Feb 28th, 2010 Boot Tray Featuring Pg. 7 Organizing and Cleaning Ideas For a New Year Great Winter Beater Ideas One-of-a-Kind Regal Gifts Over 170 New Items Call your Regal Representative today! Big Ideas... Small Prices SPECIAL OFFER ! With every $30 Order... Set of 3 /&8 /&8 only Contents $3.98 Airline Approved Over-the-Door Porcelain Hooks (Set of 3) Toiletry Travel Kit Wide-mouth, easy-fill plastic This set of three metal hangers fits conveniently over travel bottles in a convenient travel kit. Fill shampoo, virtually any door to provide you with alternate storage conditioner and lotions in seconds. Breeze through space for your hats, jackets, sweaters, housecoat, or security. Includes 3 Flip Top Bottles (3oz each), 1 Spray other apparel. (6”) Bottle (3oz), and set of coded adhesive labels. Airline approved! (Kit: 8” x 6” x 2”) PW88863 $3.98 HG335 $12.98 200% COMPLETE CONFIDENCE GUARANTEE! 100% merchandise satisfaction guarantee 100% Regal Head Offi ce guarantee If you are not satisfi ed simply return the product to We guarantee your satisfaction with your Independent your Independent Regal Representative within 60 days Regal Representative and with Regal! You can purchase for a prompt exchange or refund! (personalized items with complete confi dence and can contact us anytime and opened CDs or books are not returnable, unless of at [email protected] or 1-800-565-3130 for prompt course, it is our mistake.) customer service. Helpful Living Ask Your Rep for our new Personal Care , Health & Mobilit y Ideas for Better Living Helpful Living Ideas Catalogue Our product partners have been bringing us so many great new ideas for health, personal care and grooming ideas that we couldn’t fi t them all into our regular catalogue! So we have launched a new 32 page catalogue fi lled from cover to cover with amazing ideas to make life easier. -

Course Outlines

COURSE OUTLINE: HST732 - HEALTH AND SAFETY Prepared: Hairstyling Department Approved: Martha Irwin, Chair, Community Services and Interdisciplinary Studies Course Code: Title HST732: HEALTH AND SAFETY Program Number: Name 6350: HAIRSTYLIST LEVEL I Department: HAIRSTYLIST Semesters/Terms: 19F Course Description: Upon successful completion, the apprentice is able to facilitate the provision of healthy and safe working environments and perform sanitization procedures in accordance with related health regulations and legislation. Total Credits: 2 Hours/Week: 2 Total Hours: 18 Prerequisites: There are no pre-requisites for this course. Corequisites: There are no co-requisites for this course. Vocational Learning 6350 - HAIRSTYLIST LEVEL I Outcomes (VLO's) VLO 1 Complete all work in adherence to professional ethics, government regulations, addressed in this course: workplace standards and policies, and according to manufacturers specifications as Please refer to program web page applicable. for a complete listing of program VLO 2 Facilitate the provision of healthy and safe working environments and perform outcomes where applicable. sanitization procedures in accordance with related health regulations and legislation. VLO 3 Apply entrepreneurial skills to the operation and administration of a hair stylist business. VLO 5 Develop and use client service strategies that meet and adapt to individual client needs and expectations. Essential Employability EES 1 Communicate clearly, concisely and correctly in the written, spoken, and visual form Skills (EES) addressed in that fulfills the purpose and meets the needs of the audience. this course: EES 2 Respond to written, spoken, or visual messages in a manner that ensures effective communication. EES 4 Apply a systematic approach to solve problems. -

Interactive Virtual Hair Salon Walt Disney Feature Animation Burbank, CA 91521

Kelly Ward* Interactive Virtual Hair Salon Walt Disney Feature Animation Burbank, CA 91521 Nico Galoppo Ming Lin Department of Computer Science Abstract University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill User interaction with animated hair is desirable for various applications but difficult Chapel Hill, NC 27599 because it requires real-time animation and rendering of hair. Hair modeling, including styling, simulation, and rendering, is computationally challenging due to the enormous number of deformable hair strands on a human head, elevating the com- putational complexity of many essential steps, such as collision detection and self- shadowing for hair. Using simulation localization techniques, multi-resolution repre- sentations, and graphics hardware rendering acceleration, we have developed a physically-based virtual hair salon system that simulates and renders hair at acceler- ated rates, enabling users to interactively style virtual hair. With a 3D haptic inter- face, users can directly manipulate and position hair strands, as well as employ real- world styling applications (cutting, blow-drying, etc.) to create hairstyles more intuitively than previous techniques. 1 Introduction User interaction with animated hair is useful for various applications. For example, virtual environments depicting human avatars require a hair model- ing system capable of animating and rendering hair at interactive rates. Due to the performance requirement, many interactive hair modeling algorithms tend to lack important, complex features of hair, including hair interactions, dy- namic clustering of hair strands, and intricate self-shadowing effects. Often, realistic hair appearance and behavior are compromised for real-time interac- tion with hair. Because the shape of the hair model and other properties are typically dictated by hairstyling, it is an important step to modeling hair. -

Lois Sonstegard

Lois Sonstegard An extremely successful woman of many skills, Lois Sonstegard has aspired to greatness in an array of entrepreneurial business categories. Through a series of serendipitous events, Sonstegard magically launched a unique new business enterprise that she really never dreamed of in her early career. Today, she is respected as ‘THE Upstyle Hair Design Resource’. Lois Sonstegard was born in the USA, yet she ventured to Japan with her parents at the young age of three —experiencing her third birthday while aboard a ship. Her parents were missionaries in Japan after World War Two, for thirty years. Japan became home as she lived and studied until the end of her first year of university, becoming fluent in Japanese. She returned to the United States at the age of nineteen where she completed her undergraduate education. Sonstegard’s early career dreams led her to a very specialized PhD in Hospital Management and Finance as well as marketing and finance MBA’s. At first she was a noted specialist in women’s healthcare and high risk obstetrics, having written three books and published numerous articles. With a never-ending drive to succeed, ongoing education and pure enthusiasm in hand, Sonstegard ran services for women and children. Sonstegard eventually moved out of the hospital arena and stated her own home textile business manufacturing bed and bath items. Devin Lane Collections became a nationally respected fine home furnishings company, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The textile business was very demanding, while working with some of the top retailers and department stores across the USA. -

A Simulation-Based VR System for Interactive Hairstyling∗

A Simulation-based VR System for Interactive Hairstyling∗ Kelly Ward† Nico Galoppo Ming C. Lin The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill fwardk,nico,[email protected] ABSTRACT We have developed a physically-based VR system that enables users to interactively style dynamic virtual hair by using multi- resolution simulation techniques and graphics hardware rendering acceleration for simulating and rendering hair in real time. With a 3D haptic interface, users can directly manipulate and position hair strands, as well as employ real-world styling applications (cutting, blow-drying, etc.) to create hairstyles more intuitively than previ- ous techniques. 1 INTRODUCTION Virtual environments created for interactive hairstyling can be used to understand and specify detailed hair properties for several appli- cations, including cosmetic prototyping, education and entertain- ment, and cosmetologist training. Accurate virtual hairstyling re- quires both high performance simulation and realistic rendering to Figure 1: Hairstyle interactively created using our system. enable interactive manipulation and incorporation of fine details. The appearance of hairstyles results from physical properties of itive 3D user interface, allowing the users to directly manipu- hair and hair mutual interactions. Therefore, hair dynamics should late the hair in a manner similar to real-world hairstyling. be incorporated to mimic the process of real-world hairstyle cre- ation. However, due to the performance requirement, many inter- • Visually plausible rendering: By exploiting the capability active hair modeling algorithms tend to lack important, complex of programmable graphics hardware and multi-resolution rep- features of hair, including hair interactions, dynamic clustering of resentations, we can render plausible hair appearance due to hair strands, and intricate self-shadowing effects. -

Strands and Hair

Strands and Hair - Modeling, Simulation and Rendering Sunil Hadap, Marie-Paule Cani, Florence Bertails, Ming Lin, Kelly Ward, Stephen Marschner, Tae-Yong Kim, Zoran Kacic-Alesic To cite this version: Sunil Hadap, Marie-Paule Cani, Florence Bertails, Ming Lin, Kelly Ward, et al.. Strands and Hair - Modeling, Simulation and Rendering. SIGGRAPH 2007 - 34 International Conference and Exhibition on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Aug 2007, San Diego, United States. pp.1-150, 10.1145/1281500.1281689. inria-00520193 HAL Id: inria-00520193 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00520193 Submitted on 22 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. STRANDS AND HAIR MODELING,ANIMATION, AND RENDERING SIGGRAPH 2007 Course Notes, (Course #33) May 2, 2007 Course Organizer: Sunil Hadap Presenters: Sunil Hadap Marie-Paule Cani Ming Lin Adobe Systems1 INP Grenoble / INRIA University of North Carolina [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tae-Yong Kim Florence Bertails Steve Marschner Rhythm&Hues Studio University of British Columbia Cornell University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kelly Ward Zoran Kaciˇ c-Alesi´ c´ Walt Disney Animation Studios Industrial Light+Magic [email protected] [email protected] 1formerly at PDI/DreamWorks Contents Introduction 5 Course Abstract . -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,168,538 B2 Pefia (45) Date of Patent: Jan

US00716.8538B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,168,538 B2 Pefia (45) Date of Patent: Jan. 30, 2007 (54) OVERHEAD STORAGE DEVICE FOR 4,350,850 A * 9/1982 Kovacik et al. ....... 191,122 R ELECTRICAL TOOLS AND METHOD OF 4.378.473 A * 3/1983 Noorigian .............. 191,122 R CREATING AWORK ZONE 4,437,624 A * 3/1984 Rosenberg .................. 242,381 4,844,373 A * 7/1989 Fike, Sr. .................. 242.588.1 Inventor: 5,101,082 A * 3/1992 Simmons et al. ...... 191,122 R (76) Dantia Peña, 3133 1/2 Hood St., D337,309 S 7/1993 Mally Dallas, TX (US) 75219 5,379,903 A 1, 1995 Smith 5,547,393 A 8, 1996 Jansen (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,690,198 A * 11/1997 Lohr ..................... 191,122 R patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,913.487 A * 6/1999 Leatherman ............. 242,378.4 U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 6,305,388 B1 10/2001 Zeller 6,331,121 B1* 12/2001 Raeford, Sr. ................ 439,501 (21) Appl. No.: 10/992,414 6,591,952 B1 7/2003 Randall (22) Filed: Nov. 18, 2004 * cited by examiner Primary Examiner Mark T. Le (65) Prior Publication Data (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm—Schultz & Associates, P.C. US 2005/0106935 A1 May 19, 2005 (57) ABSTRACT (51) Int. C. H02G II/02 (2006.01) The preferred embodiment of the invention includes a casing (52) U.S. Cl. ................................ 191/12.2 R: 191/12.4 that encloses an extension cord system. -

In-Conversation-With-Exceptional

About Monica Bhide I am an engineer-turned-writer based out of Washington, DC. I have been published in many major national and international publications, including Food & Wine, The New York Times, Parents, Cooking Light, Prevention, Health, SELF, Bon Appetit, Saveur, and many more. I wrote a weekly syndicated column for Scripps Howard Media called “Seasonings” and am a frequent contributor to NPR’s Kitchen Window and AARP-The Magazine. My work has garnered numerous accolades, such as my food essays being included in three Best Food Writing anthologies (2005, 2009 and 2010). I have published three cookbooks, the latest being Modern Spice: Inspired Indian Flavors for the Contemporary Kitchen (Simon & Schuster, 2009). My spice app, iSPICE, was just released for Apple products. 2 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Aarti Sequeira, Food Network star 7 Allison Winn Scotch, New York Times best-selling novelist 11 Amanda Hesser, co-creator of the revolutionary site Food 52 15 Joan Nathan, best-selling cookbook author 19 Corinne Trang, award-winning cookbook author 22 Andrea King Collier, award-winning author and essayist 27 Andrea Nguyen, best-selling cookbook author 31 Carla Hall, co-host, ABC’s The Chew 34 Camille Noe Pagán, debut novelist and longtime Professional writer 40 Clotilde Dusoulier, best-selling cookbook author and blogger 44 Heidi Swanson, best-selling cookbook author and blogger 48 Daisy Martinez, Food Network star 51 Dana Cowin, editor-in-chief, Food & Wine magazine 55 Dorie GreensPan, legendary cookbook author 58 Elise Bauer,