Diagnoses of Death During the Holodomor of 1932–33 As a Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dynamics of FM Frequencies Allotment for the Local Radio Broadcasting

DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING IN UKRAINE: 2015–2018 The Project of the National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine “Community Broadcasting” NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 Overall indicators As of 14 December 2018 local radio stations local radio stations rate of increase in the launched terrestrial broadcast in 24 regions number of local radio broadcasting in 2015―2018 of Ukraine broadcasters in 2015―2018 The average volume of own broadcasting | 11 hours 15 minutes per 24 hours Type of activity of a TV and radio organization For profit radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations Non-profit (communal companies, community organizations) radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 The competitions held for available FM radio frequencies for local radio broadcasting competitions held by the National Council out of 97 FM frequencies were granted to the on consideration of which local radio stations broadcasters in 4 format competitions, were granted with FM frequencies participated strictly by local radio stations Number of granted Number of general Number of format Practical steps towards implementation of the FM frequencies competitions* competitions** “Community Broadcasting” project The -

Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian

Geoffrey Hull and Halyna Koscharsky1 Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian When compared with its two large neighbours, Russian and Polish, the Ukrainian language presents a picture of striking internal variation. Not only are Ukrainian dialects more mutually divergent than those of Polish or of territorially more widespread Russian,2 but on the literary level the language has long been characterized by the existence of two variants of the standard which have never been perfectly harmonized, in spite of the efforts of nationalist writers for a century and a half. While Ukraine’s modern standard language is based on the eastern dialect of the Kyiv-Poltava-Kharkiv triangle, the literary Ukrainian cultivated by most of the diaspora communities continues to follow to a greater or lesser degree the norms of the Lviv koiné in 1 The authors would like to thank Dr Lance Eccles of Macquarie University for technical assistance in producing this paper. 2 De Bray (1969: 30-35) identifies three main groups of Russian dialects, but the differences are the result of internal evolutionary divergence rather than of external influences. The popular perception is that Russian has minimal dialectal variation compared with other major European languages. Maximilian Fourman (1943: viii), for instance, told students of Russian that the language ‘is amazingly uniform; the same language is spoken over the vast extent of the globe where the flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics flies; and you will be understood whether you are speaking to a peasant or a university professor. There are no dialects to bother you, although, of course, there are parts of the Soviet Union where Russian may be spoken rather differently, as, for instance, English is spoken differently by a Londoner, a Scot, a Welshman, an Irishman, or natives of Yorkshire or Cornwall. -

Kiev 1941: Hitler's Battle for Supremacy in the East

Kiev 1941 In just four weeks in the summer of 1941 the German Wehrmacht wrought unprecedented destruction on four Soviet armies, conquering central Ukraine and killing or capturing three-quarters of a million men. This was the battle of Kiev – one of the largest and most decisive battles of World War II and, for Hitler and Stalin, a battle of crucial importance. For the first time, David Stahel charts the battle’s dramatic course and after- math, uncovering the irreplaceable losses suffered by Germany’s ‘panzer groups’ despite their battlefield gains, and the implications of these losses for the German war effort. He illuminates the inner workings of the German army as well as the experiences of ordinary soldiers, showing that with the Russian winter looming and Soviet resistance still unbroken, victory came at huge cost and confirmed the turning point in Germany’s war in the east. David Stahel is an independent researcher based in Berlin. His previous publications include Operation Barbarossa and Germany’s Defeat in the East (Cambridge, 2009). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 210.212.129.125 on Sat Dec 22 18:00:30 WET 2012. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139034449 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2012 Kiev 1941 Hitler’s Battle for Supremacy in the East David Stahel Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 210.212.129.125 on Sat Dec 22 18:00:30 WET 2012. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139034449 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2012 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107014596 c David Stahel 2012 This publication is in copyright. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Sustainable Development of Obolon Corporation Official Report

2013–2014 Sustainable Development of Obolon Corporation official report © Obolon Corporation, 2014 1 CONTENTS CORPORATION PRODUCTION PEOPLE 2 Appeal from the President 29 Production Facilities Structure 46 Working Environment 3 Social Mission 36 Brand portfolio 51 Life and Health 5 Reputation 39 Quality Management 54 Ethics and Equal Rights 7 Business Operations Standards 44 Innovations 56 Personnel Development 10 Corporate Structure 45 Technologies 58 Incentives and Motivation 18 Corporate Management 21 Stakeholders ECONOMICS ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY 60 Financial and Economic Results 69 Efficient Use of Resources 74 Development of Regions 62 Production Indicators 72 Wasteless Production 87 Promotion of Sports 63 Efficient Activity 90 Educational Projects 66 Risks 92 Sponsorship and Volunteering 96 Report overview 97 Sustainable development plans 99 Contacts 100 GRI © Obolon Corporation, 2014 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF OBOLON CORPORATION OFFICIAL REPORT 2013/14 2 CORPORATION APPEAL FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Partners, I am pleased to present Obolon Corporation's sixth Sustainability Report. This document summarizes the company's information on all socially important initiatives in the eight regions of Ukraine and presents the corporation's specific achievements in raising community life quality, minimizing environment impact, and improving employment practices over the year 2013 and the first half of 2014. This year's report is the first one to demonstrate the social, environmental and economic impact of Obolon Corporation in the regions where its facilities are located. Since the publication of the first Non-Financial Report, the Obolon Corporation has made significant progress on its way to sustainability. The commitment of our employees, implementation of several products and organizational innovations, as well as significant reduction of its environmental impact allowed the Corporation reinforce its status as a reliable and responsible member of the Ukrainian community and strengthen its market positions. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Kyiv Kyiv Lviv Lviv ... Kyiv Kyiv Sumy ... Kyiv Zaporizhia Ternopil Kyiv

Rank University Town 1 National Technical University of Ukraine Kyiv Polytechnic Institute Kyiv 2 Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Kyiv 3 Ivan Franko National University of Lviv Lviv 4 Lviv Polytechnic National University Lviv ... 5 Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University Kyiv 6 National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Kyiv 7 Sumy State University Sumy ... 8 National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine Kyiv 9 Zaporizhzhya National University Zaporizhia 10 Ternopil State Medical University Ternopil 11 National Pedagogical Dragomanov University Kyiv 12 O.M. Beketov National University of Urban Economy in Kharkiv Kharkiv ... 13 V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University Simferopol 14 National Mining University Dnipro ... 15 V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University Kharkiv 16 Vinnytsia National Technical University Vinnytsia 17 National University of Pharmacy Kharkiv 18 National Aviation University Kyiv ... 19 Odessa National University Odesa ... 20 Melitopol State Pedagogical University Melitopol 21 National University of Food Technologies Kyiv 22 Uman State Pedagogical University Uman 23 National Technical University Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute Kharkiv ... 24 Ternopil National Economic University Ternopil 25 Tavria State Agrotechnological University Melitopol 26 Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University Kharkiv 27 Kremenchuk Mykhailo Ostrohradskyi National University Kremenchuk 28 Bukovinian State Medical University Chernivtsi 29 National University of Ostroh Academy Ostroh 30 Dnipropetrovsk National University -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

Science and Education a New Dimension

www.seanewdim.com Science and Education a New Dimension. Humanities and Social Sciences, VI(26), I.: 156, 2018 www.seanewdim.com p-ISSN 2308-5258 e-ISSN 2308-1996 VI(26), Issue 156, 2018 SCIENCE AND EDUCATION A NEW DIMENSION https://doi.org/10.31174/SEND-HS2018-156VI26 Humanities and Social Sciences www.seanewdim.com Science and Education a New Dimension. Humanities and Social Sciences, VI(26), I.: 156, 2018 www.seanewdim.com Editorial board Editor-in-chief: Dr. Xénia Vámos Honorary Senior Editor: Jenő Barkáts, Dr. habil. Nina Tarasenkova, Dr. habil. Andriy Myachykov, PhD in Psychology, Senior Lecturer, Department of Oleg Melnikov, Doctor of Science in Pedagogy, Belarusian State Psychology, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Northumbria University, University, Belarus Northumberland Building, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom Perekhrest Alexander, Doctor of Science in History, Prof. habil., Bohdan Edvard Ayvazyan, Doctor of Science in Pedagogy, National Institute of Khmelnitsky National University in Cherkasy, Ukraine Education, Yerevan, Armenia Riskeldy Turgunbayev, CSc in Physics and Mathematics, associated Ferenc Ihász, PhD in Sport Science, Apáczai Csere János Faculty of the professor, head of the Department of Mathematical Analysis, Dean of the Universityof West Hungary Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of the Tashkent State edagogical Ireneusz Pyrzyk, Doctor of Science in Pedagogy, Dean of Faculty of University, Uzbekistan Pedagogical Sciences, University of Humanities and Economics in Roza Uteeva, Doctor of Science in Pedagogy, Head of the Department of Włocławek, Poland Algebra and Geometry, Togliatti StateUniversity, Russia Irina Malova, Doctor of Science in Pedagogy, Head of Department of Seda K. Gasparyan, Doctor of Science in Philology, Department of methodology of teaching mathematics andinformation technology, English Philology, Professor and Chair, Yerevan State University, Bryansk State University named after Academician IG Petrovskii, Russia Armenia Irina S. -

Ukraine: Improving Milk Supply in Northern Ukraine

FAO INVESTMENT CENTRE / EBRD REPORT SERIES - N. 18 - SEPTEMBER 2013 COOPERATION PROGRAMME Ukraine: Improving Milk Supply in Northern Ukraine Ukraine Northern in Supply Milk Improving Ukraine: Please address comments and inquiries to: Ukraine FAO FAO INVESTMENT CENTRE / EBRD COOPERATION PROGRAMME. Investment Centre Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Viale delle Terme di Caracalla - 00153 Rome - ITALY E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.fao.org/tc/tci FAO web site: www.fao.org Improving Milk Supply in Northern Ukraine Technical assistance to Ukraine’s dairy sector Report series - 18 N. ISBN 978-92-5-107938-6 9 789251 079386 I3446E/1/09.13 FAO INVESTMENT CENTRE / EBRD REPORT SERIES - N. 18 - SEPTEMBER 2013 COOPERATION PROGRAMME Ukraine Improving Milk Supply in Northern Ukraine Technical assistance to Ukraine’s dairy sector The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) or the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO or EBRD. -

Ukr Glpm A2l 20150210.Pdf

22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E 36°0'0!!"E 37°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 39°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 41°0'0"E Michurinsk !! !! !! p E Yelets Lipetsk a !! Homyel N M BELARUS I ! g ! o ! ! ! N A n Brest " 0 Pinsk ' i 0 ° 2 5 n !Horodnya R !Shostka ! Pustohorod n ! Kursk K ! ! a Voronezh !Kuznetsovs'k ! ! l Hlukhiv ! P Lebedyn Krolevets' U Chernihiv ! VOLYNS'KA ! Staryy s ! c o RIVNENS'KA ! Oskol Ovruch Shestovytsya ! i Chornobyl'! CHERNIHIVS'KA ! ! Kovel' !Konotop t !Lublin ! ZHYTOMYRS'KA s RUSSIAN i SUMS'KA N !Nizhyn " 0 ' 0 g FEDERATION ° ! Korosten' Sumy 1 ! 5 o Volodymyr-Volyns'kyy !Kostopil' ! o L Luts'k ! ! !Romny Malyn ! l Borodyanka Novovolyns'k ! o !Rivne ! Novohrad-Volyns'kyy Vyshhorod !Pryluky Lebedyn Belgorod a (!o (!o ! ! !! ! Zdolbuniv ! ! r Sokal' Kiev ! Dubno Irpin Brovary e o ! Lokhvytsya ! \! Chervonohrad ! POLAND Netishyn o ! Boryspil' ! (! n Slavuta ! !Okhtyrka Vovchans'k ! o Yahotyn o ! (! ! ! Korostyshiv ! e Pyryatyn Zhytomyr ! ! ! G Brody ! Ozerne Vasylkiv KYYIVS'KA ! Fasti!v N ! Kremenets' Obukhiv " 0 ! ! ' Myrhorod Kharkiv 0 Lubny ! o! ° Rzeszow Bila ! ! 0 o 5 L'VIVS'KA Berdychiv ! Tserkva Uzyn Korotych (!o Beregovoye ! ! ! ! ! ! ! o! o Kaniv Merefa Chuhuyiv Horodok (! Starokostyantyniv ! o o ! Kupjansk o L'viv Zolotonosha POLTAVS'KA ! ! Krasyliv ! Poltava ! ! Lozovaya Khmil'nyk ! ! Kupyansk-Uzlovoy ! Volochys'k ! Sambir Ternopil' ! ! o o Suprunovka (! Khmel'nyts'kyy ! ! ! Cherkasy KHARKIVS'KA Kalynivka o ! Krasnohrad ! (! Stebnyk o ! ! ! Ivanivka -

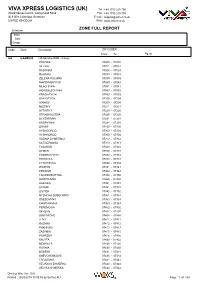

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA