Essays on Invertebrate Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoologische Mededeelingen

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDEELINGEN UITGEGEVEN VANWEGE 's RIJKS MUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE te Deel V. Aflevering 4. LEIDEN XIV. - ZUR DEUTUNG DER DE HAAN'SCHEN LAUBHEU- SCHRECKEN. VON DR. H. KARNY- Im Begriffe, nach Niederlandisch-Ostindien auszureisen, benutzte ich einen mebrwocbentlichen Aufenthalt in Holland zum Studium der De Haan'schen Orthopterentypen, die im Leidener Museum aufbewahrt sind. Es schien mir dies umso wichtiger, als so manche der yon De Haan aufgestellten Arten den neueren Monograpben nicbt vorlagen und ihre Deutung daher in der modernen Literatur vielfach zweifelhaft und strittig geblieben ist. Besonderen Dank scbulde ich hier den Herren Director Dr. van Oort und Konservator van Eecke, die mir in der liebenswur- digsten und entgegenkommendsten Weise das wertvolle Material zur Un- tersuchung uberliessen. Behindert wurde meine Arbeit einigermaassen durch den Umstand, dass ich meine eigene orthopterologische Bibliotbuk hier nicht zur Ver- fugung hatte, die Bibliothek des Leidener Museums aber nur wenige orthopterologische Arbeiten besitzt. In dieser Situation half mir aber Herr Professor Dr. W. Roepke von der Landbouw-Hoogeschool in Wa- geningen aus, indem er mir die in seinem Besitz befindlichen Mono- graphien von Brunner und Redtenbacher fur die Dauer meiner Unter- suchungen zur Verfugung stellte. Auch ihm sei an dieser Stelle fiir seine bereitwillige Aushilfe der warmste Dank ausgesprochen. STEKOPELMATINAE. Locusta (Rhaphidophorus) cubaensis. De Haan, 1842, Bijdragen, p. 218. Diese Spezies wurde von Brunner meiner Ansicht nach wohl richtig gedeutet (Monogr., p. 282), aber ich muss zu seiner Beschreibung doch einiges hinzufiigen. (lO-Xi-1920) 140 ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDEELINGEN — DEEL V. In der De Haan'schen Sammlung liegt ein einziges Exemplar (cT) vor, mit dem man nach den Brunner'schen Tabellen (p. -

Orthoptera): a Comparative Analysis Using

Morphological determinants of carrier frequency signal in katydids 1 1 Morphological determinants of carrier frequency signal 2 in katydids (Orthoptera): a comparative analysis using 3 biophysical evidence 4 5 Fernando Montealegre-Z1*, Jessica Ogden1, Thorin Jonsson1, & Carl D. Soulsbury1 6 7 1University of Lincoln, School of Life Sciences, Joseph Banks Laboratories 8 Green Lane, Lincoln, LN6 7DL, United Kingdom 9 10 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 15 Page 1 of 29 Morphological determinants of carrier frequency signal in katydids 2 16 Abstract 17 Male katydids produce mating calls by stridulation using specialized structures on the 18 forewings. The right wing (RW) bears a scraper connected to a drum-like cell known as the 19 mirror and a left wing (LW) that overlaps the RW and bears a serrated vein on the ventral 20 side, the stridulatory file. Sound is generated with the scraper sweeping across the file, 21 producing vibrations that are amplified by the mirror. Using this sound generator, katydids 22 exploit a range of song carrier frequencies (CF) unsurpassed by any other insect group, with 23 species singing as low as 600 Hz and others as high as 150 kHz. Sound generator size has 24 been shown to scale negatively with CF, but such observations derive from studies based on 25 few species, without phylogenetic control, and/or using only the RW mirror length. We 26 carried out a phylogenetic comparative analysis involving 94 species of katydids to study the 27 relationship between LW and RW components of the sound generator and the CF of the 28 male’s mating call, while taking into account body size and phylogenetic relationships. -

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Volume 24 1970 Number 4 IS PAPILlO GOTHICA (PAPILIONIDAE) A GOOD SPECIES C. A. CLARKE AND P. M. SHEPPARD Department of Medicine and Department of Genetics, University of Liverpool, England Remington (1968) has named the Papilio zelicaon-like swallowtail butterflies from a restricted geographical range (the high mountains of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming) Papilio gothica Remington. Since the criteria used by Remington for claiming the existence of this newly named species are chiefly genetical and ecological rather than the usually used morphological and behavioural ones, it seems desirable to examine the genetic evidence more critically than Remington appears to have done. Genetical Evidence Obtained by Hybridization Experiments Remington showed that P. zelicaon Lucas and P. gothica are morpho logically very similar and he also indicated that a number of specimens cannot be classified unless the place of their origin is known. However, the Fl hybrids between P. gothica and P. polyxenes Fabr. on the one hand, and P. zelicaon and P. polyxenes on the other, are distinguishable, as are thc Fl hybrids when P. bairdi is substituted for P. polyxenes. P. polyxenes and P. bairdi Edwards are much blacker insects than P. zelicaon. They show a great reduction in the amount of yellow on both wings and body. Clarke and Sheppard (1955, 1956) have demonstrated that the marked difference between the color patterns of P. polyxenes and P. zelicaon and, in fact, between P. polyxenes and the yellow Euro pean species, Papilio machaon L., is due to the presence of a single major gene which is dominant or nearly dominant in effect. -

Orthoptera: Ensifera) in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh Shah HA Mahdi*, Meherun Nesa, Manzur-E-Mubashsira Ferdous, Mursalin Ahmed

Scholars Academic Journal of Biosciences Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Acad J Biosci ISSN 2347-9515 (Print) | ISSN 2321-6883 (Online) Zoology Journal homepage: https://saspublishers.com/sajb/ Species Abundance, Occurrence and Diversity of Cricket Fauna (Orthoptera: Ensifera) in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh Shah HA Mahdi*, Meherun Nesa, Manzur-E-Mubashsira Ferdous, Mursalin Ahmed Department of Zoology, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh DOI: 10.36347/sajb.2020.v08i09.003 | Received: 06.09.2020 | Accepted: 14.09.2020 | Published: 25.09.2020 *Corresponding author: Shah H. A. Mahdi Abstract Original Research Article The present study was done to assess the species abundance, monthly occurrence and diversity of cricket fauna (Orthoptera: Ensifera) in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. A total number of 283 individuals of cricket fauna were collected and they were identified into three families, six genera and seven species. The collected specimens belonged to three families such as Gryllidae (166), Tettigoniidae (59) and Gryllotalpidae (58). The seven species and their relative abundance were viz. Gryllus texensis (36.40%), Gryllus campestris (18.37%), Lepidogryllus comparatus (3.89%), Neoconocephalus palustris (9.89%), Scudderia furcata (4.95%), Montezumina modesta (6.01%) and Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa (20.49%). Among them, highest population with dominance was Gryllus texensis (103) and lowest population was Lepidogryllus comparatus (11). Among the collected species, the status of Gryllus texensis, Gryllus campestris and Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa were very common (VC); Neoconocephalus palustris and Montezumina modesta were fairly common (FC) and Lepidogryllus comparatus and Scudderia furcata were considered as rare (R). Base on monthly occurrence 2 species of cricket were found throughout 12 months, 2 were 9-11 months, 2 were 6-8 months and 1 was 3-5 months. -

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Invasion of the Body Snatchers: the Diversity and Evolution of Manipulative Strategies in Host–Parasite Interactions

CHAPTER 3 Invasion of the Body Snatchers: The Diversity and Evolution of Manipulative Strategies in Host–Parasite Interactions † Thierry Lefe`vre,* Shelley A. Adamo, ‡ David G. Biron, Dorothe´e Misse´,* § k } David Hughes, , ,1 and Fre´de´ric Thomas*, ,1 Contents 3.1. Introduction 46 3.2. How Parasites Alter Host Behaviour 49 3.2.1. Parasitic effects on host neural function 49 3.2.2. Proteomics and proximate mechanisms 56 3.3. A Co-Evolutionary Perspective 66 3.3.1. Exploiting host-compensatory responses 66 3.2.2. Facultative virulence 72 3.4. The (River) Blind Watchmaker 75 3.5. Concluding Remarks 76 References 76 Abstract Parasite-induced alteration of host behaviour is a widespread trans- mission strategy among pathogens. Understanding how it works is an exciting challenge from both a mechanistic and an evolutionary perspective. In this review, we use key examples to examine the * Ge´ne´tique et Evolution des Maladies Infectieuses, UMR CNRS/IRD 2724, Montpellier, France { Department of Psychology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada { PIAF, UMR 547 INRA/Universite´ Blaise-Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand, France § Department of Organismal Biology, University of Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA } Institut de recherche en biologie ve´ge´tale, De´partement de sciences biologiques Universite´ de Montre´al, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada k School of Biosciences, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK 1 Both authors contributed equally Advances in Parasitology, Volume 68 # 2009 Elsevier Ltd. ISSN 0065-308X, DOI: 10.1016/S0065-308X(08)00603-9 All rights reserved. 45 46 Thierry Lefe`vre et al. proximate mechanisms by which parasites are known to control the behaviour of their hosts. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Number 35 July-September

THE BULB NEWSLETTER Number 35 July-September 2001 Amana lives, long live Among! ln the Kew Scientist, Issue 19 (April 2001), Kew's Dr Mike Fay reports on the molecular work that has been carried out on Among. This little tulip«like eastern Asiatic group of Liliaceae that we have long grown and loved as Among (A. edulis, A. latifolla, A. erythroniolde ), but which took a trip into the genus Tulipa, should in fact be treated as a distinct genus. The report notes that "Molecular data have shown this group to be as distinct from Tulipa s.s. [i.e. in the strict sense, excluding Among] as Erythronium, and the three genera should be recognised.” This is good news all round. I need not change the labels on the pots (they still labelled Among), neither will i have to re~|abel all the as Erythronlum species tulips! _ Among edulis is a remarkably persistent little plant. The bulbs of it in the BN garden were acquired in the early 19605 but had been in cultivation well before that, brought back to England by a plant enthusiast participating in the Korean war. Although not as showy as the tulips, they are pleasing little bulbs with starry white flowers striped purplish-brown on the outside. It takes a fair amount of sun to encourage them to open, so in cool temperate gardens where the light intensity is poor in winter and spring, pot cultivation in a glasshouse is the best method of cultivation. With the extra protection and warmth, the flowers will open out almost flat. -

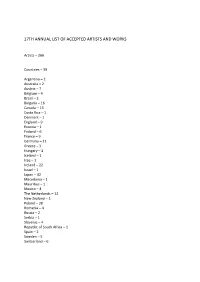

17Th Annual List of Accepted Artists and Works

17TH ANNUAL LIST OF ACCEPTED ARTISTS AND WORKS Artists – 266 Countries – 39 Argentina – 2 Australia – 2 Austria – 7 Belgium – 4 Brazil – 2 Bulgaria – 16 Canada – 13 Costa Rica – 1 Denmark – 1 England – 9 Estonia – 1 Finland – 6 France – 9 Germany – 11 Greece – 3 Hungary – 2 Iceland – 1 Iraq – 1 Ireland – 22 Israel – 1 Japan – 42 Macedonia – 1 Mauritius – 1 Mexico – 4 The Netherlands – 12 New Zealand – 1 Poland – 38 Romania – 4 Russia – 2 Serbia – 1 Slovenia – 4 Republic of South Africa – 1 Spain – 2 Sweden – 5 Switzerland – 6 Taiwan – 2 Thailand – 2 U. S. A. – 22 Venezuela – 1 Featured Artist DIMO KOLIBAROV, Bulgaria Cycle of prints Meetings with Bulgarian Printmaking Artists Presentation of the First Prize Winner of the 16th Mini Print Annual 2017 EVA CHOUNG – FUX, Austria Special Presentation FACULTY OF ARTS MARIA CURIE SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY Lublin, Poland Dr hab. Adam Panek The cycle of prints: 1. Triptych I – A, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 11 cm 2. Triptych I – B, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 9 cm 3. Triptych I – C, 2018, Linocut, 15,5 x 11 cm Dr hab. Alicja Snoch-Pawłowska The cycle of prints: 1. Diffusion 1, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm 2. Diffusion 2, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18 cm 3. Diffusion 3, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm Dr Amadeusz Popek The cycle of prints: 1. Mirage-Róża, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 2. Mirage-Pejzaż górski, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 3. Mirage, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm Mgr Andrzej Mosio The cycle of prints: 1. -

Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis Samantha Lynn Davis Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Repository Citation Davis, Samantha Lynn, "Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis" (2015). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1433. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluating threats to the rare butterfly, Pieris virginiensis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Samantha L. Davis B.S., Daemen College, 2010 2015 Wright State University Wright State University GRADUATE SCHOOL May 17, 2015 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY Samantha L. Davis ENTITLED Evaluating threats to the rare butterfly, Pieris virginiensis BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. Don Cipollini, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Don Cipollini, Ph.D. Director, Environmental Sciences Ph.D. Program Robert E.W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination John Stireman, Ph.D. Jeff Peters, Ph.D. Thaddeus Tarpey, Ph.D. Francie Chew, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Davis, Samantha. Ph.D., Environmental Sciences Ph.D. -

Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American Taxa

Mosyakin, S.L. 2018. Further new combinations in Anemonastrum (Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American taxa. Phytoneuron 2018-55: 1–11. Published 13 August 2018. ISSN 2153 733X FURTHER NEW COMBINATIONS IN ANEMONASTRUM (RANUNCULACEAE) FOR ASIAN AND NORTH AMERICAN TAXA SERGEI L. MOSYAKIN M.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2 Tereshchenkivska Street Kiev (Kyiv), 01004 Ukraine [email protected] ABSTRACT Following the proposed re-circumscription of genera in the group of Anemone L. and related taxa of Ranunculaceae (Mosyakin 2016, Christenhusz et al. 2018) and based on recent molecular phylogenetic and partly morphological evidence, the genus Anemonastrum Holub is recognized here in an expanded circumscription (including Anemonidium (Spach) Holub, Arsenjevia Starod., Tamuria Starod., and Jurtsevia Á. Löve & D. Löve) covering members of the “Anemone ” clade with x=7, but excluding Hepatica Mill., a genus well outlined morphologically and forming a separate subclade (accepted by Hoot et al. (2012) as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (Spach) Juz. sect. Hepatica (Mill.) Spreng.) within the clade earlier recognized taxonomically as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (sensu Hoot et al. 2012). The following new combinations at the section and subsection ranks are validated: Anemonastrum Holub sect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone sect. Keiskea Tamura); Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov .; Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Arsenjevia (Starod.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Arsenjevia Starod.); and Anemonastrum [sect. Anemonastrum ] subsect. Himalayicae (Ulbr.) Mosyakin, comb. nov. ( Anemone ser. Himalayicae Ulbr.). The new nomenclatural combination Anemonastrum deltoideum (Hook.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone deltoidea Hook.) is validated for a North American species related to East Asian Anemonastrum keiskeanum (T. -

Back Mr. Rudkin: Differentiating Papilio Zelicaon and Papilio Polyxenes in Southern California (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)

Zootaxa 4877 (3): 422–428 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4877.3.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:E7D8B2D6-8E1B-4222-8589-EAACB4A65944 Welcome back Mr. Rudkin: differentiating Papilio zelicaon and Papilio polyxenes in Southern California (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) KOJIRO SHIRAIWA1 & NICK V. GRISHIN2 113634 SW King Lear Way, King City, OR 97224, USA. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6235-634X 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Departments of Biophysics and Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Cen- ter, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75390-9050, USA. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4108-1153 Abstract We studied wing pattern characters to distinguish closely related sympatric species Papilio zelicaon Lucas, 1852 and Papilio polyxenes Fabricius, 1775 in Southern California, and developed a morphometric method based on the ventral black postmedian band. Application of this method to the holotype of Papilio [Zolicaon variety] Coloro W. G. Wright, 1905, the name currently applied to the P. polyxenes populations, revealed that it is a P. zelicaon specimen. The name for western US polyxenes subspecies thus becomes Papilio polyxenes rudkini (F. & R. Chermock, 1981), reinstated status, and we place coloro as a junior subjective synonym of P. zelicaon. Furthermore, we sequenced mitochondrial DNA COI barcodes of rudkini and coloro holotypes and compared them with those of polyxenes and zelicaon specimens, confirming rudkini as polyxenes and coloro as zelicaon. Key words: Taxonomy, field marks, swallowtail butterflies, desert, sister species Introduction Charles Nathan Rudkin, born 1892 at Meriden, Connecticut was a passionate scholar of history of the West, espe- cially the Southwestern region.