DUNFERMLINE CARNEGIE LIBRARY Conservation Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

Gd I N Bvrgh

Item no 20 + GD IN BVRGH + THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL Central Library Conservation Plan Executive of the Council 30 November 2004 1. Purpose of report To inform the Executive of the findings of the Central Library Conservation Plan 2. Summary 2.1 The report describes the background to the Conservation Plan, presents its key findings and indicates how it can be progressed. 3. Background 3.1 A Conservation Plan is an approach to exploring the sustainable use of a cultural, or ecological asset. Its purpose is to establish and describe the historic importance of the asset and its setting: to analyse the effects of changes that have been made in the past; and to put forward policies for conservation, repair, and restoration of its historic character and features. 3.2 The Central Library conservation Plan is intended to advise future proposals for the Library and represents a first step towards Heritage Lottery Fund and Historic Scotland grant applications. 3.3 In commissioning the Conservation Plan, the Culture and Leisure Department saw it as an important first step in taking forward the work which started during the late 1980s to modernise and remodel the Central Library. 3.4 Opened in 1890, Edinburgh’s Carnegie Central Library is a landmark building, located close to the heart of the world heritage site. It is one of the Council’s major cultural assets, Its importance within the city’s cultural infrastructure is set to increase with Edinburgh’s designation as the first UNESCO City of Literature. 3.5 The Library contains unique collections of national importance centred on those of the Edinburgh Room and Scottish Library, and houses Scotland’s busiest lending library. -

The Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland ~

THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE SOCIETY OF SCOTLAND -r • . .-., - ) C , / ' ( ' ~ (( CA ITH NESS WEEKEND STUDY TOUR 16th - 18th May 1992 • • • • I • I I I I tlTIJlhJ (ii-.~ I kiln JRANSYtKSt SLCTIOH I I I ?. I I ; .. - = . - -- E. .. ==- --- !! .. - • . e . i: =='f . A ' a C i; -- • E I n, ~ ,A E ..__ ,,. ~ b P,/NCll'Al ffATtl'([) ~ : I II !o,.,,. ii•telc. l,\lrtlotl • : : ~-; ~ -~--~-J : ' I, l'J'~ff" b.x,n(.er/. ,~llttdn. I ' c vo<rlr l~wrl'lt1-tt d. hml't• f~1"'11hctt r" ltnlll}f•!Jt111n • "J'Jlf'" hl'fL t kcr11q,1tn( ,n,ts llt •:? •,,) I: PL>, N or K. I I ,_. S' F ltnte.-•!Udcs /"< i l,rt(l /in11n-/1001· h lfllt tkiorr Ft! ,o %0 JO ,IU I rt•IJc \''>lrtlntor • II I .. 5 I, ,o /2'. co,·n,9.it;rt. ll'Ot\ IW .Sbl-l 7 ' 9 " j e e e e e Acknowledgemems e The Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland would like to thank all the owners who have kindly given their permission for us to visit their property and to make this tour possible. e: Much assistance with the planning has been generously given by Lyn Leet, architect in Thurso, e Simon Montgomery and Andrew Kerr (the Kilmaichlie one). e The tour note~ have been produced courtesy o( Simpson & Brown and written by Marion Brune, Simon Green, John Sanders and Ross Sweetland, and culled from a variety of sources, especially f! the RCAHMS. The Society apologises for any errors or inadvenant infringements of copyright. e •e :9 :9 :::, 0 ·S lo ~l L..CS :::, :, ::, 13 3 ', ::, ::, \ \ ::, , / ' ::, I Su.th~ r l Md I ::, I I ::::, I I Ca."i t h "e s s I :::a I \ ::, \ / / ~ ' ' 'I ' I I \ --\ .. -

CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT Introduction the Princes Street Heritage Framework Study Area Comprises a Lo

PRINCES STREET – CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT Introduction The Princes Street Heritage Framework study area comprises a long, section of the city centre extending along the full length of Princes Street, over a single city block and bounded by Rose Street to the north. The site lies within the New Town Conservation Area and the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. The site contains a substantial number of buildings included on the Statutory List of Buildings of Historic or Architectural Interest (14 Category A, 79 Category B, and 11 Category C). The purpose of the Heritage Framework was to better understand the features, details and planned form which give the area its historic character and identity, and to provide a context for its preservation, development and management. The study established the development sequence and form of the surviving James Craig plan, the individual historic structures and the townscape. A more detailed understanding and assessment of the character, quality and comparative cultural significance of individual buildings is now required as a prerequisite to making decisions about the future of the area. Cultural significance refers to the collection of values associated with a place which together identify why it is important. The Burra Charter suggests that ‘Cultural significance is embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects’. Where decisions are being made about the future of historic buildings, their historic and architectural significance should be adequately assessed. This should form part of the master planning and design process, and the assessment undertaken at the earliest opportunity and before detailed proposals are drawn up for the regeneration. -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

University of Bath PHD Architecture, power and ritual in Scottish town halls, 1833-1973 O'Connor, Susan Award date: 2017 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 11. Oct. 2021 Architecture, Power and Ritual in Scottish Town Halls, 1833-1973 Susan O’Connor A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering June 2016 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with the author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author. -

Caisteal Inbhir Nis / Inverness Castle a Preliminary Historical Account

version 5 November 2014 Caisteal Inbhir Nis / Inverness castle A preliminary historical account Dr Aonghus MacKechnie Historic Scotland 5 September 2014 (revised 5 November) 1 version 5 November 2014 Frontispiece: undated drawing, published probably when the 1830s courthouse was being celebrated and new, and the 1840s prison yet to be built. The kilted piper indicates the new castle was to be considered in the setting of Romantic-age Highlands. The accuracy of the drawing of the old castle is difficult to judge, but that it is described as blown up by ‘the rebels’ – ie, ‘bad guys’ – also matches the ideology of the time, when efforts to build a commemorative centenary memorial at Culloden Battlefield (1846) could not be funded, a sense of collective awkwardness still in circulation over the role of the Highlands in having challenged the status quo by armed insurrection. 2 version 5 November 2014 Inverness Castle : preliminary historical account Summary Inverness Castle comprises two 19th century castellated buildings – an 1830s courthouse and an 1840s prison – built on the site of the predecessor castle and Hanoverian barracks which were blown up by Jacobites in 1746. It occupies a prominent height above the River Ness, in the heart of the city, and is easily Inverness’s most dominant structure. It is listed category A, meaning it is of national or more than national importance. The site Inverness developed in the standard way of many old Scots burghs, having an early mediaeval religious centre (here, the parish kirk), a seat of corresponding secular authority (the castle) and a settlement. The cross-roads of modern day Church Street (which connects castle and kirk) and Bridge Street / High Street (leading to the river crossing) developed from that early layout.1 The site of Inverness Castle has been claimed to have been that of an early medieval royal centre. -

THE HOME of the ROYAL SOCIETY of EDINBURGH Figures Are Not Available

THE HOME OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH Figures are not available Charles D Waterston The bicentennial history of the Royal Society of Edinburgh1, like previous accounts, was rightly concerned to record the work and achievements of the Society and its Fellows. Although mention is made of the former homes and possessions of the Society, these matters were incidental to the theme of the history which was the advancement of learning and useful knowledge, the chartered objectives of the Society. The subsequent purchases by the Society of its premises at 22–28 George Street, Edinburgh, have revealed a need for some account of these fine buildings and of their contents for the information of Fellows and to enhance the interest of many who will visit them. The furniture so splendidly displayed in 22–24 George Street dates, for the most part, from periods in our history when the Society moved to more spacious premises, or when expansion and refurbishment took place within existing accommodation. In order that these periods of acquisition may be better appreciated it will be helpful to give a brief account of the rooms which it formerly occupied before considering the Society's present home. Having no personal knowledge of furniture, I acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr Ian Gow of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and Mr David Scarratt, Keeper of Applied Art at the Huntly House Museum of Edinburgh District Council Museum Service for examining the Society's furniture and for allowing me to quote extensively from their expert opinions. -

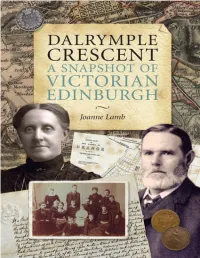

Dalrymple Crescent a Snapshot of Victorian Edinburgh

DALRYMPLE CRESCENT A SNAPSHOT OF VICTORIAN EDINBURGH Joanne Lamb ABOUT THE BOOK A cross-section of life in Edinburgh in the 19th century: This book focuses on a street - Dalrymple Crescent - during that fascinating time. Built in the middle of the 19th century, in this one street came to live eminent men in the field of medicine, science and academia, prosperous merchants and lawyers, The Church, which played such a dominant role in lives of the Victorians, was also well represented. Here were large families and single bachelors, marriages, births and deaths, and tragedies - including murder and bankruptcy. Some residents were drawn to the capital by its booming prosperity from all parts of Scotland, while others reflected the Scottish Diaspora. This book tells the story of the building of the Crescent, and of the people who lived there; and puts it in the context of Edinburgh in the latter half of the 19th century COPYRIGHT First published in 2011 by T & J LAMB, 9 Dalrymple Crescent, Edinburgh EH9 2NU www.dcedin.co.uk This digital edition published in 2020 Text copyright © Joanne Lamb 2011 Foreword copyright © Lord Cullen 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9566713-0-1 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Designed and typeset by Mark Blackadder The publisher acknowledges a grant from THE GRANGE ASSOCIATION towards the publication of this book THIS DIGITAL EDITION Ten years ago I was completing the printed version of this book. -

The Cockburn Association Edinburgh and East Lothian

THE COCKBURN ASSOCIATION EDINBURGH AND EAST LOTHIAN DOORSDAYS OPEN SAT 29 & SUN 30 SEPTEMBER 2018 Cover image: Barnton Quarry ROTOR Bunker. EDINBURGH DOORS OPEN DAY 2018 SAT 29 & SUN 30 SEPTEMBER SUPPORT THE COCKBURN ASSOCIATION AND EDINBURGH DOORS OPEN DAY Your support enables us to organise city WHO ARE WE? wide free events such as Doors Open Day, The Cockburn Association (The Edinburgh bringing together Edinburgh’s communities Civic Trust) is an independent charity which in a celebration of our unique heritage. relies on the support of its members to protect All members of the Association receive and enhance the amenity of Edinburgh. We an advance copy of the Doors Open Day have been working since 1875 to improve programme and invitations throughout the built and natural environment of the city the year to lectures, talks and events. – for residents, visitors and workers alike. If you enjoy Doors Open Days please We campaign to prevent inappropriate consider making a donation to support our development in the City and to preserve project www.cockburnassociation.org.uk/ the Green Belt, to promote sustainable donate development, restoration and high quality modern architecture. We are always happy If you are interested in joining the Association, visit us online at www.cockburnassociation. to advise our members on issues relating org.uk or feel free to call or drop in to our to planning. offices at Trunk’s Close. THE COCKBURN ASSOCIATION The Cockburn Association (The Edinburgh Civic Trust) For Everyone Who Loves Edinburgh is a registered Scottish charity, No: SC011544 TALKS & TOURS 2018 P3 ADMISSION BALERNO P10 TO BUILDINGS BLACKFORD P10 Admission to all buildings is FREE. -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. -

Abbotshall and Central Kirkcaldy Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

Abbotshall and Central Kirkcaldy Conservation Area Appraisal And Management Plan CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction and Purpose 1.1 Conservation Areas 1.2 The Purpose of this Document 1.4 Abbotshall & Central Kirkcaldy Map 2.0 Historical Development 2.1 Map of 1854 2.2 Origins of Development and Settlement 2.3 Archaeological and Historical Significance 3.0 Townscape Analysis 3.1 Architectural, Design: Local Characteristics and Materials 3.2 Contribution of Trees and Open Space 3.3 Setting and Views 3.4 Activity and Movement 3.5 Public Realm 3.6 Development Pressure 3.7 Negative Features 3.8 Buildings at Risk 4.0 Conservation Management Strategy 4.1 Management Plan 4.2 Planning Policy 4.3 Supplementary Planning Guidance 4.4 Article 4 Directions 4.5 Monitoring and Review 4.6 Further Advice Appendix 1 Abbotshall and Central Kirkcaldy Article 4 Directions Appendix 2 Street Index of Properties in the Conservation Area Description of Conservation Area Boundaries Appendix 3 Table of Listed Buildings in the Conservation Area 1.0 Introduction and Purpose 1.1 Conservation Areas In accordance with the provisions contained in the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997 all planning authorities are obliged to consider the designation of conservation areas from time to time. Abbotshall and Central Kirkcaldy Conservation Area is one of 48 conservation areas located in Fife. These are all areas of particular architectural or historic value, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance. Fife Council is keen to ensure that the quality of these areas is maintained for the benefit of present and future generations. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography.