News of the Other Tracing Identity in Scandinavian Constructions of the Eastern Baltic Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr's Årsrapport 2017

DR’S ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 01 02 DR’S ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 – INDHOLD A. LEDELSESBERETNING s.06 01 Præsentation af DR s.07 02 DR i 2017 s.12 03 DR i hoved- og nøgletal s.16 04 DR’s samfundsansvar og miljøhensyn B. LICENSREGNSKABET s.22 05 Licensregnskabet C. REGNSKAB s.26 06 Ledelsens regnskabspåtegning s.27 07 Den uafhængige revisors påtegning s.29 08 Resultatopgørelse s.30 09 Balance s.32 10 Egenkapitalopgørelse s.33 11 Pengestrømsopgørelse s.34 12 Noter til årsregnskabet D. LEDELSE s.58 13 Ledelse i DR s.64 14 Organisation s.65 15 Virksomhedsoplysninger 04 A. DR’S ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 LEDELSES- 05 BERETNING DR’S ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 01. PRÆSENTATION AF DR DR er en selvstændig offentlig institution. DR’s digitale hovedindgang på nettet er Rammerne for DR’s virksomhed fastsæt- dr.dk, hvor DR’s brugere bl.a. kan tilgå ny- tes i lov om radio- og fjernsynsvirksomhed heder, tv og radio. og tilhørende bekendtgørelser, herunder bekendtgørelse om vedtægt for DR, samt Brugerne kan desuden tilgå DR’s indhold i public service-kontrakten mellem DR og via apps til mobile enheder som tablets og kulturministeren. smartphones, herunder DRTV-appen, DR Radio-appen og DR Nyheder-appen. Til børn DR’s virksomhed finansieres gennem DR’s an- og unge-målgrupperne tilbyder DR digi- del af licensmidlerne samt gennem indtæg- tale indholdsuniverser, som er tilpasset de ter ved salg af programmer og andre ydelser. platforme, som målgrupperne anvender. DR DR skal udøve public service-virksomhed Ramasjang og DR Ultra er tilgængelige både over for hele befolkningen efter principperne via net og app. -

Mild to Moderately Severe

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Mild To Moderately Severe J D. Valencia University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Valencia, J D., "Mild To Moderately Severe" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1985. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1985 MILD TO MODERATELY SEVERE by J DANIEL VALENCIA BA University of Central Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2011 © 2011 J Daniel Valencia ii ABSTRACT Mild to Moderately Severe is an episodic memoir of a boy coming of age as a latch-key kid, living with a working single mother and partly raising himself, as a hearing impaired and depressed young adult, learning to navigate the culture with a strategy of faking it, as a nomad with seven mailing addresses before turning ten. It is an examination of accidental and cultivated loneliness, a narrative of a boy and later a man who is too adept at adapting to different environments, a reflection on relationships and popularity and a need for attention and love that clashes with a need to walk through unfamiliar neighborhoods alone. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

Media Studies

Summer School Media Studies A Level Media Students Guide A media student should have an interest in the products around them, from film to TV, video games to radio. A media student needs to be able to look at the products they consume and ask why? Why has it been made? Why has some one made this product? Why have the representations been created in that specific way? Students will often go off to study media further specialising in film, TV, business or advertisement. The Take Yotube BBC Arts, Culture and the Media Programmes Film Riot Youtube Channel 4 News & Current Affairs Feminist Frequency YouTube TED Talks Film Theorists YouTube PechaKucha 20x20 Game Theorists YouTube Cinema Sins YouTube Easy Photo Class YouTube BBC Radio 1's Screen time Podcast BBC Radio 4’s Front Row BBC Radio 1’s Movie Mixtape BBFC Podcast Media Studies Media BBC Radio 5’s Must Watch Podcast Media Masters Podcast BBC Radio 5 Kermode & Mayo Film Reviews The BBC Academy Podcast BBC Radio 4’s The Media Show Media Voices Mobile Journalism Show The Guardian IGN BFI Film Academy Den of Geek Screenskills @HoEMedia on Twitter WhatCulture Creativebloq The Student Room Adobe Photoshop Tutorials Universal Extras - be an extra! Shooting People - Jobs in Films If you would like to share what you’ve learnt, we’d love for you to produce a piece of media that we could share with other students. Introduction To: Media Studies An introduction to Media Studies and the basic skills you will need Introduction Hello and welcome to Media Studies. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of Journal Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of journal stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. A total of 28 journals were picked up in the media last week (30 November - 6 December) - our highlights include: ● An analysis of coroners’ reports published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine warning that swallowing alcohol-based hand sanitiser can kill made global headlines, including The Daily Telegraph, Hindu Business Line, and Newsweek. ● A dtb editorial warning that the ‘Mum test’ is not enough to convince people to get the COVID-19 jab was picked up by The Daily Telegraph, OnMedica and The Nation Sri Lanka. ● Research in The BMJ suggesting that birth defects may be linked to a greater risk of cancer in later life was covered by the Daily Mail, HuffPost UK, and The Sun. PRESS RELEASES The BMJ | Archives of Disease in Childhood BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine | Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin EXTERNAL PRESS RELEASES Archives of Disease in Childhood | British Journal of Ophthalmology OTHER COVERAGE The BMJ | Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases BMJ Case Reports | BMJ Global Health BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health | BMJ Open BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care | BMJ Open Gastroenterology BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine | BMJ Paediatrics Open BMJ Open Respiratory Research | British Journal of Sports Medicine Gut | Heart Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health | Journal of Investigative -

Has TV Eaten Itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00Pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT

May 2015 Has TV eaten itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT Hosted by Romesh Ranganathan. Nominated films and highlights of the awards ceremony will be broadcast by Sky www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society May 2015 l Volume 52/5 From the CEO The general election are 16-18 September. I am very proud I’d like to thank everyone who has dominated the to say that we have assembled a made the recent, sold-out RTS Futures national news agenda world-class line-up of speakers. evening, “I made it in… digital”, such a for much of the year. They include: Michael Lombardo, success. A full report starts on page 23. This month, the RTS President of Programming at HBO; Are you a fan of Episodes, Googlebox hosts a debate in Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom; David or W1A? Well, who isn’t? This month’s which two of televi- Abraham, CEO at Channel 4; Viacom cover story by Stefan Stern takes a sion’s most experienced anchor men President and CEO Philippe Dauman; perceptive look at how television give an insider’s view of what really Josh Sapan, President and CEO of can’t stop making TV about TV. It’s happened in the political arena. AMC Networks; and David Zaslav, a must-read. Jeremy Paxman and Alastair Stew- President and CEO of Discovery So, too, is Richard Sambrook’s TV art are in conversation with Steve Communications. Diary, which provides some incisive Hewlett at a not-to-be missed Leg- Next month sees the 20th RTS and timely analysis of the election ends’ Lunch on 19 May. -

{Download PDF} the Stars Are Right Ebook Free Download

THE STARS ARE RIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chaosium RPG Team | 180 pages | 14 May 2008 | CHAOSIUM INC | 9781568821771 | English | Hayward, United States The Stars are Right PDF Book Photo Courtesy: P! Natalie Dormer and Gene Tierney With HBO's massively successful fantasy series Game of Thrones finally over and a whole slew of spinoff series coming down the pipeline soon enough , many fans of the show are left wondering what star Natalie Dormer will do next. For instance, they've starred in the Ocean's film series and Burn After Reading. Here's What to Expect for the Super Bowl. It can't be denied that everyone knows her name. It can sometimes feel like society has hit a new level of boy craziness sometimes. Lea Michele and Naya Rivera The cast of Glee was riddled with as much in-house drama as a real-life glee club. When Lea Michele started gaining a massive fanbase, other characters started receiving fewer lines and less-important storylines. If more than one person in your household wants to vote, each person will need to create a personal ABC account. More than one person can use the same computer or device to vote, but each person needs to log out after voting. The achievement or service doesn't involve participation in aerial flight, and it can occur during engagement against a U. As such, it must be said that both these two stars deserve far more praise than they typically receive. As it turns out, the coffee business didn't quite work out. -

Saturday, July 7, 2018 | 15 | WATCH Monday, July 9

6$785'$<-8/< 7+,6,6123,&1,& _ )22' ,16,'( 7+,6 :((. 6+233,1* :,1(6 1$',<$ %5($.6 &KHFNRXW WKH EHVW LQ ERWWOH 683(50$5.(7 %(67 %8<6 *UDE WKH ODWHVW GHDOV 75,(' $1' 7(67(' $// 7+( 58/(6 :H FKHFN RXW WRS WUDYHO 1$',<$ +XVVDLQ LV D KDLUGU\HUV WR ORRN ZDQWDQGWKDW©VZK\,IHHOVR \RXGRQ©WHDWZKDW\RX©UHJLYHQ WRWDO UXOHEUHDNHU OXFN\§ WKHQ \RX JR WR EHG KXQJU\§ JRRG RQ WKH PRYH WKHVH GD\V ¦,©P D 6KH©V ZRQ 7KLV UHFLSH FROOHFWLRQ DOVR VHHV /XFNLO\ VKH DQG KXVEDQG $EGDO SDUW RI WZR YHU\ %DNH 2II SXW KHU IOLS D EDNHG FKHHVHFDNH KDYH PDQDJHG WR SURGXFH RXW D VOHZ RI XSVLGH GRZQ PDNH D VLQJOH FKLOGUHQ WKDW DUHQ©W IXVV\HDWHUV GLIIHUHQW ZRUOGV ¤ ,©P %ULWLVK HFODLU LQWR D FRORVVDO FDNH\UROO VR PXFK VR WKDW WKH ZHHN EHIRUH 5(/$; DQG ,©P %DQJODGHVKL§ WKH FRRNERRNV DQG LV DOZD\V LQYHQW D ILVK ILQJHU ODVDJQH ZH FKDW VKH KDG DOO WKUHH *$0(6 $336 \HDUROG H[SODLQV ¦DQG UHDOO\ VZDS WKH SUDZQ LQ EHJJLQJ KHU WR GROH RXW IUDJUDQW &RQMXUH XS RQ WKH WHOO\ ¤ SUDZQ WRDVW IRU FKLFNHQ DQG ERZOIXOV RI ILVK KHDG FXUU\ EHFDXVH ,©P SDUW RI WKHVH 1DGL\D +XVVDLQ PDJLFDO DWPRVSKHUH WZR DPD]LQJ ZRUOGV , KDYH ¦VSLNH§ D GLVK RI PDFDURQL ¦7KH\ ZHUH DOO RYHU LW OLNH WHOOV (//$ FKHHVH ZLWK SLFFDOLOOL ¤ WKH ¨0XPP\ 3OHDVH FDQ ZH KDYH 086,& QR UXOHV DQG QR UHVWULFWLRQV§ :$/.(5 WKDW 5(/($6(6 ZRPDQ©V D PDYHULFN WKDW ULJKW QRZ"© , ZDV OLNH ¨1R +HQFH ZK\ WKUHH \HDUV RQ IURP IRRG LV PHDQW +RZHYHU KHU DSSURDFK WR WKDW©V WRPRUURZ©V GLQQHU ,©YH :H OLVWHQ WR WKH ZLQQLQJ *UHDW %ULWLVK %DNH 2II WR EH IXQ FODVKLQJDQG PL[LQJ IODYRXUVDQG MXVW FRRNHG LW HDUO\ \RX©YH JRW ODWHVW DOEXPV WKH /XWRQERUQ -

Anne Raduns Divorce Guide

(888) 740-5140 221 Northwest 4th Street, Ocala, FL 34475 [email protected] www.ocalafamilylaw.com (888) 740-5140 www.ocalafamilylaw.com Caring and Aggressive Legal Representa on “Protecting your interests and helping you make it successfully through your divorce is not just my profession — it’s my passion!” Anne E. Raduns, PA Your Skilled, Trusted and Compassionate Coach Focused on a Fair Resolution — but Ready to During Divorce Aggressively Litigate During divorce, you'll be faced with decisions that aff ect the The ideal strategy to pursue during divorce is one that rest of your life. And that's why during this stressful me, you achieves a fair and equitable se lement — and avoids me need more than a capable family lawyer — you also need consuming, stressful, and costly li ga on. Anne strives to an experienced, caring and forward-looking coach who will work with the other family lawyer to achieve an op mal help you move ahead with your life. At the Ocala, Florida se lement. However, when this approach is not in your law fi rm of Anne E. Raduns, PA, experienced Family Lawyer best interest or not possible given the circumstances of your Anne Raduns is both the skilled divorce lawyer and dedicated unique issues, be assured that Anne has the in-depth legal counsellor of law you need. Having prac ced exclusively in knowledge, confidence, and experience to aggressively rep- family law for many years, Anne will guide, mo vate, advo- resent you in court and protect your interests. cate and zealously protect you and your family's interests. -

Media Development 2019

MEDIA DEVELOPMENT 2019 DR Audience Research Department’s annual report on the development of use of electronic media in Denmark Content Intro · page 3 About value and volume Chapter 1 · page 5 Calm before the media storm Chapter 2 · page 13 Streaming toddlers Chapter 3 · page 16 The path through the streaming jungle Chapter 4 · page 20 A new generation’s music discovery Chapter 5 · page 24 The past media year Chapter 6 · page 27 Breaking news: The Danes still watch TV news Chapter 7 · page 31 Value in a new media reality Chapter 8 · page 34 Record many mature streamers Chapter 9 · page 38 Esports on the edge of the big breakthrough Chapter 10 · page 43 This app would like to send you notifications Chapter 11 · page 46 Women are from Kanal 4, Men are from TV3 Max 2019 About value and volume It buzzes and hums in the pockets of the Danes. The eternal battle for the users’ attention has gradually had the result that we have started removing the worst disturbances from our mobiles. Notifications may be a good thing as long as they provide value and are relevant, but it is also found that far from all disturbances are worth the attention. Because what is actually worth the time? BY DENNIS CHRISTENSEN When glancing at my mobile, the first thing I see is the breaking news about Brex- it. Before I even get to open the news, the notification is replaced by a reminder from my calendar about a meeting. Both Instagram and Twitter also want my atten- tion, and on Messenger I have received a message from my wife. -

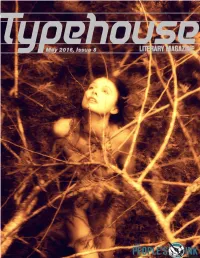

1 Typehouse Literary Magazine Issue 8, May 2016 2 Call for Submissions

1 Typehouse Literary Magazine Issue 8, May 2016 2 Call for Submissions Typehouse is a writer-run, literary magazine based out of Portland, Oregon. We publish non-fiction, genre fiction, literary fiction, poetry and visual art. We are always looking for well-crafted, previously unpublished, writing that seeks to capture an awareness of the human predicament. f you are interested in submitting fiction, poetry, or visual art, email your submission as an attachment or within the body of the email along with a short bio to: typehouse"peoples-ink.com Editors #al $ryphin %indsay &owler Michael Munkvold Cover Photo Pastoral: &ae ( by ). *iding and +. %a &ey ,+ee page -./ 0stablished (123 Published Triennially http!44typehousemagazine.com4 3 Typehouse Literary Magazine Table of Contents: Fiction: 5unky Town 5aley '. &edor 6 +tall $. ). +hepard 27 The )lpine 'all )manda McTigue 33 ) 'arvel of 'odern +cience $eorge )llen Miller 61 n the Wine-8ark 8eep +haun 9ossio 66 *eturned &ire :. 0dward ;ruft << +hampoo +amantha Pilecki -< )lchemy ;athryn %ipari -- Poetry: William Ogden 5aynes (< *achael )dams =6 +teve %uria )blon 63 *obert 9rown <- Visual Art: Tagen T. 9aker 26 >assandra +ims ;night 32 &abrice 9. Poussin =. ). *iding <( 8enny 0. Marshall 211 Issue 8, May 2016 4 Haley Fedor is a queer author from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Section 8 Magazine, The Fem, Guide to Kulchur Magazine, Literary Orphans, Crab Fat Literary Magazine, and the anthology Dispatches from Lesbian America. She was nominated for the 2014 Pushcart Prize, and is currently a graduate student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Hunky Town Haley M Fedor The car went ?uickly over a bump, and Michael hit his head on the lid of the trunk. -

DR's Public Service- Redegørelse 2020

DR’s public service-redegørelse 2020 DR’s public service- redegørelse 202020 20 1 Indholdsfortegnelse 0. Forord 3 1. Rammer for DR’s public service-redegørelse 4 2. Fordeling af programtyper på tv, radio og digitalt 5 3. Borgernes brug af DR’s programudbud 10 4. Borgernes vurdering af DR’s indholdskvalitet 12 5. Nyheder og aktualitet 14 6. Regional dækning 16 7. Dansk kultur 18 8. Dansk dramatik 20 9. Dansk musik 22 10. Børn og beskyttelse af børn 25 11. Unge 27 12. Folkeoplysning, uddannelse og læring 29 13. Idræt 30 14. Dækning af mindretal i grænselandet, grønlandske og færøske forhold og de nordiske lande 31 15. Dansksprogede programmer og dansk sprog 33 16. Europæiske programmer 37 17. Tilgængelighed 38 18. Dialog med befolkningen 41 19. Udlægning af produktion og produktionsfaciliteter 42 20. Dansk film 44 21. Rapportering af udgifter fordelt på formål og kanaler 45 2 0. Forord Coronapandemien satte sit tydelige præg på hele det danske I 2020 satte DR også fokus på den danske natur med temaet samfund i 2020. Den påvirkede også DR’s sendeflade og ind- ’Vores Natur’. Temaet blev foldet ud i den unikke naturserie hold. Begivenheder og programmer blev aflyst, og samtidig ’Vilde, vidunderlige Danmark’, som bragte seerne helt tæt opstod der behov for oplysning om corona – og for tilbud, som på dyrerigets store dramaer i den danske natur. Og i radioen kunne bringe folk sammen. gav en lang række naturprogrammer nye perspektiver på den danske natur. ’Vores Natur’ blev gennemført i partnerskab med Med udgangspunkt i ’Sammen om det vigtige’ – DR’s strategi Friluftsrådet, Naturstyrelsen og Danske Naturhistoriske Museer, frem mod 2025 – prioriterede DR i 2020 fortsat at understøtte som stod klar med aktiviteter og naturformidling i hele landet, demokratiet, bidrage til dansk kultur og styrke fællesskaber i ligesom landets biblioteker byggede videre på DR’s indhold.