The Writings in Prose and Verse of Rudyard Kipling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bahă Yyih Khăˇnum

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bahíyyih Khánum by Baha'i World Centre This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.guten- berg.org/license This is a copyrighted Project Gutenberg eBook, details below. Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. Title: Bahíyyih Khánum Author: Baha'i World Centre Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 19242] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BAHÍYYIH KHÁNUM*** Bahíyyih Khánum by Baha'i World Centre Edition 1, (September 2006) Baha'i Terms of Use You have permission to freely make and use copies of the text and any other information ("Content") available on this Site including printing, emailing, posting, distributing, copying, downloading, uploading, transmitting, displaying the Content in whole or in part subject to the following: 1. Our copyright notice and the source reference must be attached to the Content; 2. The Content may not be modified or altered in any way except to change the font or appearance; 3. The Content must be used solely for a non-commercial purpose. Although this blanket permission to reproduce the Content is given freely such that no special permission is required, the Bahá’í International Community retains full copyright protection for all Content included at this Site under all applicable national and international laws. For permission to publish, transmit, display or otherwise use the Content for any commercial purpose, please contact us (http://reference.bahai.org/en/contact.html). -

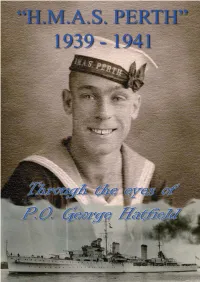

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Rudyard Kipling Bibliothèque Nobel 1907

Bibliothèque Nobel 1907 Rudyard Kipling Œuvres A Tale of Two Cities 107.0017e Wilful-Missing" 107.0006 M. I. 107.0006 Poésie lyrique: Poème Soldier an' Sailor Too" 107.0006 Soldier an' Sailor Too" 107.0962e Cells 107.0006 Columns 107.0006 Hadramauti 107.0006 Mary, Pity Women!" 107.0006 The Widow's Party 107.0006 Mary, Pity Women!" 107.0962e The Jacket 107.0006 For to Admire" 107.0006 Griffen's Debt 107.0017e Christmas in India 107.0017e Shillin' a Day 107.0006 The Service Man" 107.0006 The Betrothed 107.0017e Chant-Pagan 107.0006 The Betrothed 107.0032e Half-Ballade of Waterval 107.0006 The Song of the Women 107.0032e The Sergeant's Weddin' 107.0962e The Song of the Women 107.0017e The 'Eathen 107.0962e The Story of the Gadsbys - L'Envoi 107.0020e Follow me 'Ome" 107.0006 Gentlemen-Rankers 107.0006 Follow me 'Ome" 107.0962e The Mare's Nest 107.0006 The Instructor 107.0006 In Springtime 107.0017e Boots 107.0006 One Viceroy Resigns 107.0032e The Married Man 107.0006 L'Envoi 107.0006 Lichtenberg 107.0006 L'Envoi 107.0017e Arithmetic on the Frontier 107.0032e To the Unknown Goddess 107.0017e The Sergeant's Weddin' 107.0006 A Tale of Two Cities 107.0006 The Moral 107.0006 A Tale of Two Cities 107.0032e The Mother-Lodge 107.0006 To the Unknown Goddess 107.0032e Arithmetic on the Frontier 107.0006 The Moon of Other Days 107.0017e Pagett, M.P. 107.0017e One Viceroy Resigns 107.0017e Pagett, M.P. -

Sample Preview

Preview Sample A Publication of Complete Curriculum *LEUDOWDU0, © Complete Curriculum All rights reserved; No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the Publisher or Authorized Agent. Published in electronic format in the U.S.A. Preview Sample TM Acknowledgments Complete Curriculum’s K-12 curriculumKDV been team-developed by a consortium of teachers, administrators, educational and subject matter specialists, graphic artists and editors. In a collaborative environment, each professional participant contributed to ensuring the quality, integrity and effectiveness of each Compete Curriculum resource was commensurate with the required educational benchmarks and contemporary standards Complete Curriculum had set forth at the onset of this publishing program. Preview Sample Lesson 1 Vocabulary List One Frequently Used Words Objective: The student will recognize frequently encountered words, read them fluently, and understand the words and their history. Lesson 2 Make Me Laugh! Thomas Nast – “Cartoonist for America” Objective: The student will be introduced to analyzing the various ways that visual image-makers (graphic artists, illustrators) communicate information and affect impressions and opinions. Lesson 3 Written Humor The Ransom of Red Chief by O. Henry Objective: The student will analyze global themes, universal truths, and principles within and across texts to create a deeper understanding by drawing conclusions, making inferences, and synthesizing. Lesson 4 Writing Diary Entries Objective: The student will set a purpose, consider audience, and replicate authors’ styles and patterns when writing a narrative as a diary entry. Lesson 5 Preview Vocabulary Assessment—List One Journal Writing Objective: The student will demonstrate understanding of and familiarity with the Vocabulary words introduced in Vocabulary List One. -

Works in the Kipling Collection "After" : Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1924 BOOK PR 4854 R4 1924 "After"

Works in the Kipling Collection Title Main Author Publication Year Material Type Call Number "After" : Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1924 BOOK PR 4854 R4 1924 "After" : Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1924 BOOK PR 4854 R4 1924 "Collectanea" Rudyard Kipling. Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1908 BOOK PR 4851 1908 "Curry & rice," on forty plates ; or, The ingredients of social life at Atkinson, George Francklin. 1859 BOOK DS 428 A76 1859 "our station" in India / : "Echoes" by two writers. Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1884 BOOK PR 4854 E42 1884 "Kipling and the doctors" : Bateson, Vaughan. 1929 BOOK PR 4856 B3 "Teem"--a treasure-hunter / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1935 BOOK PR 4854 T26 1935 "Teem"--a treasure-hunter / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1938 BOOK PR 4854 T26 1938 "The Times" and the publishers. Publishers' Association. 1906 BOOK Z 323 T59 1906 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905a "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905a "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1906 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1906 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905 "They"; and, The brushwood boy / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1925 BOOK PR 4854 T352 1925 "They"; and, The brushwood boy / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1926 BOOK PR 4854 T352 1926 [Autograph letter from Stephen Wheeler, editor of the Civil & Wheeler, Stephen, 1854-1937. 1882 BOOK PR 4856 A42 1882 military gazette, reporting his deputy [Diary, 1882]. -

Twenty Poems From

THE P OEMS O F RUDYARD K I PLI NG B A - OOM BALLADS 1 82m! Tfi and ARR CK R ( o m ) . ue 2nd /z u fld TH E S EVEN S ( 1 3 T o m ) . F V NATI O ! Tk ousand THE I E NS ( n ot ) . DEP ARTMENTAL DITTI ES (8 1 r! o wn Svc o un in uck am 63 ne t e ach Cr , b d b r , . u v o l me . a v bo un in lim lambs k in t Fc . 8 o d te p , p , gil p, a m 65 ne t e h v lu e . c o Fca 8v o o und in c o th to s . ne t e ach p . , b l , gilt p , 5 v o ume l . 71 Ed ti o n I n 8 v ua o ume s . S 7 8 S er v i ce i . l q re ( a 8v o 5 ne t e ach v o ume c p. , 3 . l . TWENTY POEMS FRO M RUDYARD KIP LI NG ! M b th k l s o a K ab y ro er nee s , s ys ir, ! To s t a nd b r a ss h a th -w s one in e en i e , ' But in my bro ther s v oice I h e ar M o w n u a w d a o rr ie s ine n ns ere g . Hi s Go d is as h is fat e a s s i s gn . -

BENJAMIN CARRE RESIDENCE 2754 North Woodshire Drive CHC-2018-802-HCM ENV-2018-803-CE

BENJAMIN CARRE RESIDENCE 2754 North Woodshire Drive CHC-2018-802-HCM ENV-2018-803-CE Agenda packet includes: 1. Final Determination Staff Recommendation Report 2. Commission/ Staff Site Inspection Photos—March 29, 2018 3. Categorical Exemption 4. Under Consideration Staff Recommendation Report 5. Historic-Cultural Monument Application Please click on each document to be directly taken to the corresponding page of the PDF. Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2018-802-HCM ENV-2018-803-CE HEARING DATE: May 3, 2018 Location: 2754 North Woodshire Drive TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 4 – Ryu PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Hollywood 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA 90012 Neighborhood Council: Hollywood United Legal Description: Tract TR 6450, Block 5, Lot 7 EXPIRATION DATE: May 15, 2018 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the BENJAMIN CARRE RESIDENCE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/APPLICANT: Frederica Sainte-Rose 2754 North Woodshire Drive Los Angeles, CA 90068 PREPARER: Mitzi March Mogul 1725 Wellington Road Los Angeles, CA 90019 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the subject property a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7. 2. Adopt the staff report and findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of Planning [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken -

Marzieh Gail Dawn Over Mount Hira and Other Essays

MARZIEH GAIL DAWN OVER MOUNT HIRA AND OTHER ESSAYS GR GEORGE RONALD OXFORD George Ronald 46 High Street, Kidlington, Oxford Introduction, selection and notes © George Ronald 1976 ISBN 0 85398 0632 Cased 0 85398 0640 Paper SET IN GREAT BRITAIN BY W & J MACKAY LIMITED AND PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. ii Contents FOREWORD vii I Paradise Brought Near Dawn Over Mount Hira 1 From Sa‘dí’s Garden of Roses 9 ‘Alí 12 From the Sayings of ‘Alí 14 II Take the Gentle Path There Was Wine 19 ‘For Love of Me …’ 29 Notes on Persian Love Poems 33 Current Mythology 43 III Headlines Tomorrow The Carmel Monks 49 Headlines Tomorrow 50 IV Bright Day of the Soul That Day in Tabríz 57 Bright Day of the Soul 62 The White Silk Dress 80 The Poet Laureate 91 Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl in America 105 iii V Age of All Truth The Goal of a Liberated Mind 117 This Handful of Dust 121 The Rise of Women 128 Till Death Do Us Part 137 Atomic Mandate 145 VI The Divine Encounter Echoes of the Heroic Age 153 Millennium 165 Easter Sunday 170 Bahá’u’lláh’s Epistle to the Son of the Wolf 176 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in America 184 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: Portrayals from East and West 194 VII Where’er You Walk In the High Sierras 219 Midnight Oil 222 Will and Testament 226 Where’er You Walk 232 NOTES AND REFERENCES 237 iv Foreword THE UNION OF EAST AND WEST has been and is the dream of many. -

THE MEHER MESSAGE [Vol

THE MEHER MESSAGE [Vol. III ] January, 1931 [ No. 1] An Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook July 2020 All words of Meher Baba copyright © Avatar Meher Baba Perpetual Public Charitable Trust Ahmednagar, India Source: The Meher Message THE MEHERASHRAM INSTITUTE ARANGAON AHMEDNAGAR Proprietor and Editor.—Kaikhushru Jamshedji Dastur M.A., LL.B. eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust's eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust's web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba's lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects-such as lineation and font- the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. Moreover, they are often much more readable, especially in the case of older books, whose discoloration and deteriorated condition often makes them partly illegible. -

WW1 COMMEMORATIVE ISSUE 201809 Gramophone Gramophone 04/06/2018 14:56 Page 1

: Bulletin WW1 COMMEMORATIVE ISSUE 201809_Gramophone_Gramophone 04/06/2018 14:56 Page 1 The ‘Moonlight’ sonata sounds newly minted in this remarkable reading, Pavel Kolesnikov’s hallmark virtues of ‘intelligence, sensitivity and imagination’ (Gramophone) guaranteeing a very special Beethoven recital indeed. CDA68237 Available Friday 31 August 2018 Beethoven: Moonlight Sonata & other piano music PAVEL KOLESNIKOV piano A deeply impressive A successor to and eclectic Howard Shelley’s selection of shorter earlier Dussek choral works from recordings presents one of England’s another three fine brightest composer concertos. prospects. CDA68211 Available Friday 31 August 2018 CDA68191 Available Friday 31 August 2018 Owain Park: Choral Works Dussek: Piano Concertos TRINITY COLLEGE CHOIR Opp 3, 14 & 49 CAMBRIDGE HOWARD SHELLEY piano STEPHEN LAYTON conductor ULSTER ORCHESTRA COMINGSOON… Iain Farrington’s Chopin: Cello Sonata; Schubert: Arpeggione Sonata Steven Isserlis (cello), Dénes Várjon (piano) Bronsart & Urspruch: Piano Concertos Emmanuel Despax (piano), BBC Scottish SO, Eugene Tzigane (conductor) chamber version Liszt: New Discoveries, Vol. 4 Leslie Howard (piano) Machaut: The gentle physician The Orlando Consort of this monumental Vaughan Williams: A Sea Symphony BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Chorus, Martyn Brabbins The Passing-Measures Mahan Esfahani (harpsichord) work is a perfect Févin: Missa Ave Maria & Missa Salve sancta parens The Brabant Ensemble, Stephen Rice (conductor) match for these young voices. CDA68242 Available Friday 31 August 2018 Brahms: Ein deutsches Requiem YALE SCHOLA CANTORUM DAVID HILL conductor OTHER LABELS AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD ON OUR WEBSITE CDs, MP3 and lossless downloads of all our recordings are available from www.hyperion-records.co.uk Gimell HYPERION RECORDS LTD, PO BOX 25, LONDON SE9 1AX · [email protected] · TEL +44 (0)20 8318 1234 FRMS BULLETIN Autumn 2018 No. -

Sea Warfare, by Rudyard Kipling

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Sea Warfare, by Rudyard Kipling This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Sea Warfare Author: Rudyard Kipling Release Date: February 6, 2006 [EBook #17689] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SEA WARFARE *** Produced by Thierry Alberto, Jeannie Howse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net SEA WARFARE BY RUDYARD KIPLING MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 1916 CONTENTS PAGE THE FRINGES OF THE FLEET 1 TALES OF "THE TRADE" 93 DESTROYERS AT JUTLAND 145 THE FRINGES OF THE FLEET (1915) In Lowestoft a boat was laid, Mark well what I do say! And she was built for the herring trade, But she has gone a-rovin', a-rovin', a-rovin', The Lord knows where! They gave her Government coal to burn, And a Q.F. gun at bow and stern, And sent her out a-rovin', etc. Her skipper was mate of a bucko ship Which always killed one man per trip, So he is used to rovin', etc. Her mate was skipper of a chapel in Wales, And so he fights in topper and tails— Religi-ous tho' rovin', etc. Her engineer is fifty-eight, So he's prepared to meet his fate, Which ain't unlikely rovin', etc. Her leading-stoker's seventeen, So he don't know what the Judgments mean, Unless he cops 'em rovin', etc. -

Kipling, Rudyard

Kim Kipling, Rudyard Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. Kim Table Of Content About Phoenix−Edition Copyright 1 Kim Kim by Rudyard Kipling 2 Kim Chapter 1 O ye who tread the Narrow Way By Tophet−flare to judgment Day, Be gentle when 'the heathen' pray To Buddha at Kamakura! Buddha at Kamakura. He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib−Gher − the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum. Who hold Zam−Zammah, that 'fire−breathing dragon', hold the Punjab, for the great green−bronze piece is always first of the conqueror's loot. There was some justification for Kim − he had kicked Lala Dinanath's boy off the trunnions − since the English held the Punjab and Kim was English. Though he was burned black as any native; though he spoke the vernacular by preference, and his mother−tongue in a clipped uncertain sing−song; though he consorted on terms of perfect equality with the small boys of the bazar; Kim was white − a poor white of the very poorest. The half−caste woman who looked after him (she smoked opium, and pretended to keep a second−hand furniture shop by the square where the cheap cabs wait) told the missionaries that she was Kim's mother's sister; but his mother had been nursemaid in a Colonel's family and had married Kimball O'Hara, a young colour− sergeant of the Mavericks, an Irish regiment. He afterwards took a post on the Sind, Punjab, and Delhi Railway, and his Regiment went home without him.