Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnolia Finally Flowers in Boston

The "Hope of Spring" Magnolia Finally Flowers in Boston Stephen A. Spongberg and Peter Del T~edici After a difficult start, Magnolia biondii from China flowered in the Arboretum for the first time in March of 1991. The spring and early summer of 1991 at the biloba, and Magnolia biondii. While we were Arnold Arboretum were extraordinary with eager to examine each of these in turn, and regard to the heavy flowering of many of the to document their flowering with voucher trees and shrubs within the Arboretum’s col- herbarium specimens and photographs, the lections. Nor was this phenomenon restricted first flowering of the last-named magnolia to the confines of the Arboretum, for across presented us with the opportunity to examine the Northeast crabapples, flv~y.riWg dog- the flowers of tills species and to fix its posi- woods, and other ornamental trees and shrubs tion in the classification of the genus T A _ _ _ _ _ 7 ’ »Ync~llrar~ an ~lwnr~~n~nr ~f 1-.lv~,-,.‘ ‘ly.y i ^..t_^.7 tvtu~ttVllCt. the season as outstanding. The relatively mild winter of 1990-1991 and the abundant rainfall Early History of the Species that fell during the summer of 1990 combined Magnolia biondii was first described by the to make the spring of 1991 an exceptionally Italian botanist Renato Pampanini in 1910 floriferous one. based on specimens collected in Hubei Not only was there an abundance of bloom, Province in central China in 1906 by the but many of the newer accessions at the Italian missionary and naturalist, P. -

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon Kalmiopsis leachiana ISSN 1055-419X Volume 20, 2013 &ôùĄÿĂùñü KALMIOPSIS (irteen years, fourteen issues; that is the measure of how long Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon, ©2013 I’ve been editing Kalmiopsis. (is is longer than I’ve lived in any given house or worked for any employer. I attribute this longevity to the lack of deadlines and time clocks and the almost total freedom to create a journal that is a showcase for our state and society. (ose fourteen issues contained 60 articles, 50 book reviews, and 25 tributes to Fellows, for a total of 536 pages. I estimate about 350,000 words, an accumulation that records the stories of Oregon’s botanists, native )ora, and plant communities. No one knows how many hours, but who counts the hours for time spent doing what one enjoys? All in all, this editing gig has been quite an education for me. I can’t think of a more e*ective and enjoyable way to make new friends and learn about Oregon plants and related natural history than to edit the journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon. Now it is time for me to move on, but +rst I o*er thanks to those before me who started the journal and those who worked with me: the FEJUPSJBMCPBSENFNCFST UIFBVUIPSTXIPTIBSFEUIFJSFYQFSUJTF UIFSFWJFXFST BOEUIF4UBUF#PBSETXIPTVQQPSUFENZXPSL* especially thank those who will follow me to keep this journal &ôùĄÿĂ$JOEZ3PDIÏ 1I% in print, to whom I also o*er my +les of pending manuscripts, UIFTFSWJDFTPGBOFYQFSJFODFEQBHFTFUUFS BSFMJBCMFQSJOUFSBOE &ôùĄÿĂùñü#ÿñĂô mailing service, and the opportunity of a lifetime: editing our +ne journal, Kalmiopsis. -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

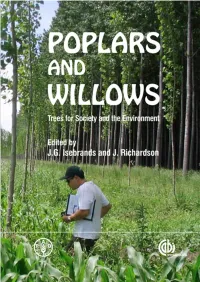

Poplars and Willows: Trees for Society and the Environment / Edited by J.G

Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment This volume is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Victor Steenackers. Vic, as he was known to his friends, was born in Weelde, Belgium, in 1928. His life was devoted to his family – his wife, Joanna, his 9 children and his 23 grandchildren. His career was devoted to the study and improve- ment of poplars, particularly through poplar breeding. As Director of the Poplar Research Institute at Geraardsbergen, Belgium, he pursued a lifelong scientific interest in poplars and encouraged others to share his passion. As a member of the Executive Committee of the International Poplar Commission for many years, and as its Chair from 1988 to 2000, he was a much-loved mentor and powerful advocate, spreading scientific knowledge of poplars and willows worldwide throughout the many member countries of the IPC. This book is in many ways part of the legacy of Vic Steenackers, many of its contributing authors having learned from his guidance and dedication. Vic Steenackers passed away at Aalst, Belgium, in August 2010, but his work is carried on by others, including mem- bers of his family. Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment Edited by J.G. Isebrands Environmental Forestry Consultants LLC, New London, Wisconsin, USA and J. Richardson Poplar Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Published by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CABI CABI is a trading name of CAB International CABI CABI Nosworthy Way 38 Chauncey Street Wallingford Suite 1002 Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Boston, MA 02111 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 800 552 3083 (toll free) Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Tel: +1 (0)617 395 4051 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi.org © FAO, 2014 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

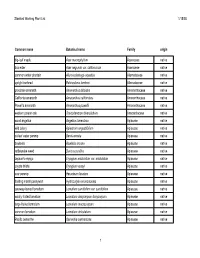

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

OR Wild -Backmatter V2

208 OREGON WILD Afterword JIM CALLAHAN One final paragraph of advice: do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am — a reluctant enthusiast.... a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of your- selves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it is still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for awhile and contemplate the precious still- ness, the lovely mysterious and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive and I promise you this much: I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men with their hearts in a safe-deposit box and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this: you will outlive the bastards. —Edward Abbey1 Edward Abbey. Ed, take it from another Ed, not only can wilderness lovers outlive wilderness opponents, we can also defeat them. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men (sic) UNIVERSITY, SHREVEPORT UNIVERSITY, to do nothing. MES SMITH NOEL COLLECTION, NOEL SMITH MES NOEL COLLECTION, MEMORIAL LIBRARY, LOUISIANA STATE LOUISIANA LIBRARY, MEMORIAL —Edmund Burke2 JA Edmund Burke. 1 Van matre, Steve and Bill Weiler. -

Eastern North American Plants in Cultivation

Eastern North American Plants in Cultivation Many indigenous North American plants are in cultivation, but many equally worthy ones are seldom grown. It often ap- pears that familiar native plants are taken for granted, while more exotic ones - those with the glamor of coming from some- where else - are more commonly cultivated. Perhaps this is what happens everywhere, but perhaps this attitude is a hand- me-down from the time when immigrants to the New World brought with them plants that tied them to the Old. At any rate, in the eastern United States some of the most commonly culti- vated plants are exotic species such as Forsythia species and hy- brids, various species of Ligustrum, Syringa vulgaris, Ilex cre- nata, Magnolia X soulangiana, Malus species and hybrids, Acer platanoides, Asiatic rhododendrons (both evergreen and decidu- ous) and their hybrids, Berberis thunbergii, Abelia X grandi- flora, Vinca minor, and Pachysandra procumbens, to mention only a few examples. This is not to imply, however, that there are few indigenous plants that have "made the grade," horticulturally speaking, for there are many obvious successes. Some plants, such as Cornus florida, have been adopted immediately and widely, but others, such as Phlox stolonifera ’Blue Ridge’ have had to re- ceive an award in Europe before drawing the attention they de- serve here, much as American singers used to have to acquire a foreign reputation before being accepted as worthwhile artists. Examples among the widely grown eastern American trees are Tsuga canadensis; Thuja occidentalis; Pinus strobus (and other species); Quercus rubra, Q. palustris, and Q. -

Staff Summary for April 15-16, 2020

Item No. 30 STAFF SUMMARY FOR APRIL 15-16, 2020 30. SHASTA SNOW-WREATH CESA PETITION Today’s Item Information ☐ Action ☒ Consider and potentially act on the petition, DFW’s evaluation report, and comments received to determine whether listing Shasta snow-wreath (Neviusia cliftonii) as a threatened or endangered species under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) may be warranted. Summary of Previous/Future Actions • Received petition Sep 30, 2019 • FGC transmitted petition to DFW Oct 10, 2019 • Published notice of receipt of petition Nov 22, 2020 • Public receipt of petition Dec 11-12, 2019; Sacramento • Received DFW 90-day evaluation report Feb 21, 2020; Sacramento • Today, determine if petitioned action Apr 15-16, 2020; Teleconference may be warranted Background A petition to list Shasta snow-wreath as endangered under CESA was submitted by Kathleen Roche and the California Native Plant Society on Sep 30, 2019 (Exhibit 1). On Oct 10, 2019, FGC staff transmitted the petition to DFW for review. A notice of receipt of petition was published in the California Regulatory Notice Register on Nov 22, 2019. California Fish and Game Code Section 2073.5 requires that DFW evaluate the petition and submit to FGC a written evaluation with a recommendation, which was received at FGC’s Feb 21, 2020 meeting. The evaluation report (Exhibit 2) delineates each of the categories of information required for a petition, evaluates the sufficiency of the available scientific information for each of the required components, and incorporates additional relevant information that DFW possessed or received during the review period. Today’s agenda item follows the public release and review period of the evaluation report prior to FGC action, as required in Fish and Game Code Section 2074. -

Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections

Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections By Emily Beech, Kirsty Shaw and Meirion Jones June 2015 Recommended citation: Beech, E., Shaw, K., & Jones, M. 2015. Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections. BGCI. Acknowledgements BGCI gratefully acknowledges the many botanic gardens around the world that have contributed data to this survey (a full list of contributing gardens is provided in Annex 2). BGCI would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in the promotion of the survey and the collection of data, including the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Yorkshire Arboretum, University of Liverpool Ness Botanic Gardens, and Stone Lane Gardens & Arboretum (U.K.), and the Morton Arboretum (U.S.A). We would also like to thank contributors to The Red List of Betulaceae, which was a precursor to this ex situ survey. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) BGCI is a membership organization linking botanic gardens is over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. www.bgci.org FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) FFI, founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, based on sound science and take account of human needs. www.fauna-flora.org GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) GTC is undertaken through a partnership between BGCI and FFI, working with a wide range of other organisations around the world, to save the world’s most threated trees and the habitats which they grow through the provision of information, delivery of conservation action and support for sustainable use. -

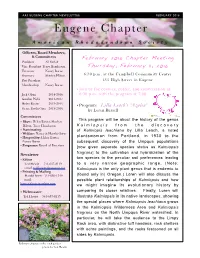

FEBRUARY 2016 Eugene Chapter

ARS EUGENE CHAPTER NEWSLETTER FEBRUARY 2016 Eugene Chapter American Rhododendron Society Officers, Board Members, & Committees February 2016 Chapter Meeting President Ali Sarlak Vice-President Terry Henderson Thursday, February 11, 2016 Treasurer Nancy Burns Secretary Sherlyn Hilton 6:30 p.m. at the Campbell Community Center Past-President 155 High Street in Eugene Membership Nancy Burns • Join us for cookies, coffee, and conversation at Jack Olson 2014-2016 6:30 p.m. with the program at 7:00. Gordon Wylie 2014-2017 Helen Baxter 2015-2018 • Program: Lilla Leach’s ‘Azalea’ Grace FowlerGore 2015-2018 by Loren Russell Committees This program will be about the history of the genus • Show: Helen Baxter, Sherlyn Hilton, Terry Henderson Kalmiopsis f r o m t h e d i s c o v e r y • Nominating: of Kalmiopis leachiana by Lilla Leach, a noted • Welfare: Nancy & Harold Greer • Hospitality: Helen Baxter, plantswoman from Portland, in 1930 to the Nancy Burns subsequent discovery of the Umpqua populations • Programs: Board of Directors [now given separate species status as Kalmiopsis fragrans] to the cultivation and hybridization of the Newsletter two species to the peculiar soil preferences leading • Editor Ted Hewitt 541-687-8119 to a very narrow geographic range. (Note: email: [email protected] Kalmiopsis is the only plant genus that is endemic to • Printing & Mailing Harold Greer 541-686-1540 (found only in) Oregon.) Loren will also discuss the email: possible plant relationships of Kalmiopsis and how [email protected] we might imagine its evolutionary history by • Webmaster comparing its closer relatives. Finally, Loren will Ted Hewitt 541-687-8119 illustrate Kalmiopsis in its native landscapes, showing the special places where Kalmiopsis leachiana grows in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness Area and Kalmiopsis fragrans on the North Umpqua River watershed. -

Public Lands Profile: Big Hammock

Public Lands Profile: Big Hammock A Land of Dramatic Contrasts Across its 800 acres, Big Hammock Natural Area showcases a fascinating diversity of natural communities of the Lower Atlantic Coastal Plain. For this reason, it was secured by the State of Georgia in 1973, and in 1976 was designated a National Natural Landmark. Despite past harvest of the native longleaf pine and extensive livestock grazing, significant habitat for rare plant and animal species remains intact. A hammock is a rise in elevation of an otherwise flat landscape. Big Hammock Natural Area is dominated by an ancient sand dune that rises from the Altamaha River floodplain to 100 feet above sea level. Between 15,000 to 30,000 years ago, water levels of the Altamaha River fluctuated more than they do now. The river was composed of many smaller braided channels in a sandy bed. During times of drought, the sands would be exposed and transported by dominant winds to the northeast side of the river, forming the dunes that remain today. Similar riverine dunes are occasional throughout Georgia’s Atlantic Coastal Plain on other rivers, such as the Ohoopee and the Ocmulgee, and form a unique part of Georgia’s landscape. It is this sand dune which underlies the natural diversity of Big Hammock NA. The ancient topography causes extreme environmental conditions that morph the vegetation into dramatic contrasts. Evergreen hardwood forest dominates the deep sands of the hammock. Natural fire is suppressed by the Altamaha River on the south side, encouraging the persistence of this fire-intolerant forest type.