Mezolith: Stone Age Dreams and Nightmares (Book 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolf Brother by Michelle Paver

Wolf Brother by Michelle Paver Overall aims of this teaching sequence. • To understand the genre of ‘quest stories; • To explore dilemmas, empathising with characters; • To consider differing viewpoints; • To build an imaginative picture of a different world; • To explore themes of bravery and loyalty though a fictional text. This teaching sequence is designed for a Year 5 or Year 6 class. Overview of this teaching sequence This teaching sequence is approximately 4 weeks long if spread out over 20 sessions. You will need to allocate time outside of the teaching sequence to read the book. Wolf Brother is an exciting adventure set 6,000 years ago during the time of the hunter gatherers. Torak, of wolf clan is the main character. His father’s death, at the hands of a gigantic bear inhabited by an evil spirit, triggers Torak’s quest - to save the forest from destruction. His loyal guide is a wolf cub and the story is told from both human and animal perspectives. There are strong themes in this story, including bravery, loyalty and a deep respect for the forest and its inhabitants. Before beginning this teaching sequence it would be helpful for children to have an insight into life at the time of the Stone Age and the life of the hunter gatherers. National Curriculum objectives covered by this sequence Reading: (Word reading / Comprehension) Writing: (Transcription / Composition) . Increase familiarity with a range of books; . Plan writing by identifying the audience for . Identify themes and conventions and and purpose of the writing, selecting the compare these across books they have read; appropriate form . -

Praise for Michelle Paver

Praise for Michelle Paver ‘Dark Matter is . [a] wild beast that grabs you by the neck’ Te Times ‘Te ultimate test of a good ghost story is, surely, whether you feel panicked reading it in bed at midnight; two-thirds through, I found myself suddenly afraid to look out of the windows, so I’ll call it a success’ Observer ‘Told in the increasingly fearful words of Jack as he writes in his journal, this is a blood-curdling ghost story, evocative not just of icy northern wastes but of a mind as, trapped, it turns in on itself ’ Daily Mail ‘Paver has created a tale of terror and beauty and wonder. Mission accomplished: at last, a story that makes you check you’ve locked all the doors and leaves you very thankful indeed for the electric light. In a world of CGI-induced chills, a good old-fashioned ghost story can still clutch at the heart’ Financial Times ‘Dark Matter is a spellbinding read – the kind of subtly unsettling, understated ghost story M.R. James might have written had he visited the Arctic’ Guardian ‘Jack becomes sure that an evil presence is trying to drive him away from Gruhuken. Paver records his terror with compassion, convincing the reader that he believes everything he records while leaving open the possibility that his isolation . has made him peculiarly susceptible to emotional disturbance. Te novel ends in tragedy that is as haunting as anything else in this deeply afecting tale of mental and physical isolation’ Sunday Times Thin-Air-prelims-ac.indd 1 21/07/2016 10:13:22 ‘It’s an elegantly told tale with a vivid sense of place – and it’s deeply scary’ Sunday Herald ‘Dark Matter is brilliant. -

Michelle Paver

Book Interview Michelle Paver Chronicles of Ancient Darkness #5: Oath Breaker ISBN13: 9780060728397 What are you working on now? Right now, I'm getting deeper and deeper into a new series, which is immensely exciting. However, like many writers, I'm a bit superstitious about discussing my stories before I've actually written them, so I'm afraid I can't tell you very much. Like Torak's story, the new series will be set in prehistoric times -- although at a slightly later period, and in a different part of the world. But that's all I can say for now! Where do you get your ideas? The short answer is that I really don't know -- they just come. But it's true to say that once I've got the bare bones of a story, I often get ideas from my own research trips to faraway places. Take Ghost Hunter, for example. The story takes place in the High Mountains, and it tells of Torak's final battle against the strongest, most terrifying Soul-Eater of all: Eostra the Eagle Owl Mage. To research the story, I traveled to Finnish Lapland in midwinter, where I went snowshoeing through the forest, following the trail of a female moose and trying (unsuccessfully) to talk to ravens. And I spent time in the mountains of northern Norway, where I encountered herds of musk oxen. They look like small, extremely shaggy bison, and they can be quite bad-tempered, so you've got to be careful not to get too close. Also, I climbed one of the mountains and fell down part of it -- which really helped me understand what Torak goes through on the Mountain of Ghosts. -

CHRONICLES of ANCIENT DARKNESS – Teachers' Notes

A BOY. A WOLF. A LEGEND FOR ALL TIME. Thousands of years ago in a world of myth, menace, natural magic and danger all around, one lonely hero Torak must begin a terrifying quest to save the world as he knows it, his only companion a wolf cub of three months old. Teachers’ Notes The Chronicles of Ancient Darkness series is suitable for children in Upper Key Stage 2 or Key Stage 3 (9–13 years). The first book in the series, Wolf Brother, works well as an independent text-based unit or can be used in contrast to other books of the quest genre. These lesson ideas and the Survival Guide classroom resource are designed to use alongside Wolf Brother without breaking the flow of the story. The lesson ideas provide opportunities to develop an understanding of this genre, explore how an author builds tension, creates realistic settings and develops rounded characters. The Survival Guide is designed to print out for each pupil to use and add information to whilst reading the story. Synopsis Imagine that the land is one dark forest. Its people are hunter-gatherers. They know every tree and herb and they know how to survive in a time of enchantment and powerful magic. Until an ambitious and malevolent force conjures a demon: a demon so evil that it can be contained only in the body of a ferocious bear that will slay everything it sees, a demon determined to destroy the world. Only one boy can stop it – 12-year-old Torak, who has seen his father murdered by the bear. -

Oath Breaker: Book 5 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

OATH BREAKER: BOOK 5 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michelle Paver | 272 pages | 04 Jun 2009 | Hachette Children's Group | 9781842551165 | English | London, United Kingdom Oath Breaker: Book 5 PDF Book Community Reviews. I especially like the parts of the story told from the wolf's POV. Deseret News. Michelle Paver was born in Central Africa, but came to England as a child. As an action, you target one undead creature you can see within 30 feet of you. When Torak's best friend is killed, he swears vengence and goes after the killer along with another best friend and her uncle. Fin-Keddin being forced back to the clan, Torak and Renn alone in the Deep Forest fighting to survive alone with waring clans all thanks to Thiazzi the Oak Mage. There is one more book in this series, but I'm tapping out here. Retrieved August 16, You can tell she What I liked: Where to start? Any enemy in the aura must make a DC 21 DC 25 if they derive their power from an entity, powerful being, or god will save to avoid being frightened. May 29, Scott rated it really liked it. The fight between Thiazzi and Torak was exhilarating. Also, for up 1 hour, you can assume the form of an angelic or devilish being by your own powers, giving the following benefits:. Children's literature portal. You either need to expend your Channel Divinity — an entirely separate action — or have someone else use a Frighten effect. He drags those who love him - Wolf, Renn, Fen-Keddin - along on his quest, and often, in spite of the evidence directly in front of him, he allows his oath of vengance to lead him down paths that are not in his best interests. -

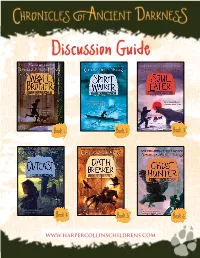

Discussion Guide

Discussion Guide Book 1 Book 2 Book 3 Book 4 Book 5 Book 6 www.harpercollinschildrens.com WOLF BROTHER DiscussiOn Guide About the Book. After his father is killed by a demon-possessed bear, Torak is left alone in the ancient Forest. He must find his way to the Mountain and ask the World Spirit for help. Captured by the Raven Clan, Torak learns about his father’s past and why a Soul-Eater created the demon bear. Led by his guide, a young orphaned wolf, and with the aid of a young woman who helps him escape from the Raven Clan, Torak seeks to fulfill the promise he made to his father—that he will find the Mountain or die trying. During their arduous journey to the Mountain, Torak must locate three of the most powerful pieces of the Nanuak to gain the World Spirit’s help. Only then will it be possible to vanquish the demon bear—but Torak’s battle with evil is far from over. Discussion Questions 6. How does Hord’s involvement with the demon bear’s creation relate to his overpowering need to be the one who saves the clans? Do you think Hord can think 1. Research information about prehistoric clans from different continents, including their traditions and cultures. What is rationally, based on what he knows and has seen? the hierarchy within each clan? How are the cultures of these clans different from or similar to cultures in today’s world? 7. Torak escapes captivity because he is helped by one of the Raven Clan (pp.