CS301 Complexity of Algorithms Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complexity Theory Lecture 9 Co-NP Co-NP-Complete

Complexity Theory 1 Complexity Theory 2 co-NP Complexity Theory Lecture 9 As co-NP is the collection of complements of languages in NP, and P is closed under complementation, co-NP can also be characterised as the collection of languages of the form: ′ L = x y y <p( x ) R (x, y) { |∀ | | | | → } Anuj Dawar University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory NP – the collection of languages with succinct certificates of Easter Term 2010 membership. co-NP – the collection of languages with succinct certificates of http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/0910/Complexity/ disqualification. Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Complexity Theory 3 Complexity Theory 4 NP co-NP co-NP-complete P VAL – the collection of Boolean expressions that are valid is co-NP-complete. Any language L that is the complement of an NP-complete language is co-NP-complete. Any of the situations is consistent with our present state of ¯ knowledge: Any reduction of a language L1 to L2 is also a reduction of L1–the complement of L1–to L¯2–the complement of L2. P = NP = co-NP • There is an easy reduction from the complement of SAT to VAL, P = NP co-NP = NP = co-NP • ∩ namely the map that takes an expression to its negation. P = NP co-NP = NP = co-NP • ∩ VAL P P = NP = co-NP ∈ ⇒ P = NP co-NP = NP = co-NP • ∩ VAL NP NP = co-NP ∈ ⇒ Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Anuj Dawar May 14, 2010 Complexity Theory 5 Complexity Theory 6 Prime Numbers Primality Consider the decision problem PRIME: Another way of putting this is that Composite is in NP. -

EXPSPACE-Hardness of Behavioural Equivalences of Succinct One

EXPSPACE-hardness of behavioural equivalences of succinct one-counter nets Petr Janˇcar1 Petr Osiˇcka1 Zdenˇek Sawa2 1Dept of Comp. Sci., Faculty of Science, Palack´yUniv. Olomouc, Czech Rep. [email protected], [email protected] 2Dept of Comp. Sci., FEI, Techn. Univ. Ostrava, Czech Rep. [email protected] Abstract We note that the remarkable EXPSPACE-hardness result in [G¨oller, Haase, Ouaknine, Worrell, ICALP 2010] ([GHOW10] for short) allows us to answer an open complexity ques- tion for simulation preorder of succinct one counter nets (i.e., one counter automata with no zero tests where counter increments and decrements are integers written in binary). This problem, as well as bisimulation equivalence, turn out to be EXPSPACE-complete. The technique of [GHOW10] was referred to by Hunter [RP 2015] for deriving EXPSPACE-hardness of reachability games on succinct one-counter nets. We first give a direct self-contained EXPSPACE-hardness proof for such reachability games (by adjust- ing a known PSPACE-hardness proof for emptiness of alternating finite automata with one-letter alphabet); then we reduce reachability games to (bi)simulation games by using a standard “defender-choice” technique. 1 Introduction arXiv:1801.01073v1 [cs.LO] 3 Jan 2018 We concentrate on our contribution, without giving a broader overview of the area here. A remarkable result by G¨oller, Haase, Ouaknine, Worrell [2] shows that model checking a fixed CTL formula on succinct one-counter automata (where counter increments and decre- ments are integers written in binary) is EXPSPACE-hard. Their proof is interesting and nontrivial, and uses two involved results from complexity theory. -

Dspace 6.X Documentation

DSpace 6.x Documentation DSpace 6.x Documentation Author: The DSpace Developer Team Date: 27 June 2018 URL: https://wiki.duraspace.org/display/DSDOC6x Page 1 of 924 DSpace 6.x Documentation Table of Contents 1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________ 7 1.1 Release Notes ____________________________________________________________________ 8 1.1.1 6.3 Release Notes ___________________________________________________________ 8 1.1.2 6.2 Release Notes __________________________________________________________ 11 1.1.3 6.1 Release Notes _________________________________________________________ 12 1.1.4 6.0 Release Notes __________________________________________________________ 14 1.2 Functional Overview _______________________________________________________________ 22 1.2.1 Online access to your digital assets ____________________________________________ 23 1.2.2 Metadata Management ______________________________________________________ 25 1.2.3 Licensing _________________________________________________________________ 27 1.2.4 Persistent URLs and Identifiers _______________________________________________ 28 1.2.5 Getting content into DSpace __________________________________________________ 30 1.2.6 Getting content out of DSpace ________________________________________________ 33 1.2.7 User Management __________________________________________________________ 35 1.2.8 Access Control ____________________________________________________________ 36 1.2.9 Usage Metrics _____________________________________________________________ -

The Complexity Zoo

The Complexity Zoo Scott Aaronson www.ScottAaronson.com LATEX Translation by Chris Bourke [email protected] 417 classes and counting 1 Contents 1 About This Document 3 2 Introductory Essay 4 2.1 Recommended Further Reading ......................... 4 2.2 Other Theory Compendia ............................ 5 2.3 Errors? ....................................... 5 3 Pronunciation Guide 6 4 Complexity Classes 10 5 Special Zoo Exhibit: Classes of Quantum States and Probability Distribu- tions 110 6 Acknowledgements 116 7 Bibliography 117 2 1 About This Document What is this? Well its a PDF version of the website www.ComplexityZoo.com typeset in LATEX using the complexity package. Well, what’s that? The original Complexity Zoo is a website created by Scott Aaronson which contains a (more or less) comprehensive list of Complexity Classes studied in the area of theoretical computer science known as Computa- tional Complexity. I took on the (mostly painless, thank god for regular expressions) task of translating the Zoo’s HTML code to LATEX for two reasons. First, as a regular Zoo patron, I thought, “what better way to honor such an endeavor than to spruce up the cages a bit and typeset them all in beautiful LATEX.” Second, I thought it would be a perfect project to develop complexity, a LATEX pack- age I’ve created that defines commands to typeset (almost) all of the complexity classes you’ll find here (along with some handy options that allow you to conveniently change the fonts with a single option parameters). To get the package, visit my own home page at http://www.cse.unl.edu/~cbourke/. -

The Polynomial Hierarchy

ij 'I '""T', :J[_ ';(" THE POLYNOMIAL HIERARCHY Although the complexity classes we shall study now are in one sense byproducts of our definition of NP, they have a remarkable life of their own. 17.1 OPTIMIZATION PROBLEMS Optimization problems have not been classified in a satisfactory way within the theory of P and NP; it is these problems that motivate the immediate extensions of this theory beyond NP. Let us take the traveling salesman problem as our working example. In the problem TSP we are given the distance matrix of a set of cities; we want to find the shortest tour of the cities. We have studied the complexity of the TSP within the framework of P and NP only indirectly: We defined the decision version TSP (D), and proved it NP-complete (corollary to Theorem 9.7). For the purpose of understanding better the complexity of the traveling salesman problem, we now introduce two more variants. EXACT TSP: Given a distance matrix and an integer B, is the length of the shortest tour equal to B? Also, TSP COST: Given a distance matrix, compute the length of the shortest tour. The four variants can be ordered in "increasing complexity" as follows: TSP (D); EXACTTSP; TSP COST; TSP. Each problem in this progression can be reduced to the next. For the last three problems this is trivial; for the first two one has to notice that the reduction in 411 j ;1 17.1 Optimization Problems 413 I 412 Chapter 17: THE POLYNOMIALHIERARCHY the corollary to Theorem 9.7 proving that TSP (D) is NP-complete can be used with DP. -

Ex. 8 Complexity 1. by Savich Theorem NL ⊆ DSPACE (Log2n)

Ex. 8 Complexity 1. By Savich theorem NL ⊆ DSP ACE(log2n) ⊆ DSP ASE(n). we saw in one of the previous ex. that DSP ACE(n2f(n)) 6= DSP ACE(f(n)) we also saw NL ½ P SP ASE so we conclude NL ½ DSP ACE(n) ½ DSP ACE(n3) ½ P SP ACE but DSP ACE(n) 6= DSP ACE(n3) as needed. 2. (a) We emulate the running of the s ¡ t ¡ conn algorithm in parallel for two paths (that is, we maintain two pointers, both starts at s and guess separately the next step for each of them). We raise a flag as soon as the two pointers di®er. We stop updating each of the two pointers as soon as it gets to t. If both got to t and the flag is raised, we return true. (b) As A 2 NL by Immerman-Szelepsc¶enyi Theorem (NL = vo ¡ NL) we know that A 2 NL. As C = A \ s ¡ t ¡ conn and s ¡ t ¡ conn 2 NL we get that A 2 NL. 3. If L 2 NICE, then taking \quit" as reject we get an NP machine (when x2 = L we always reject) for L, and by taking \quit" as accept we get coNP machine for L (if x 2 L we always reject), and so NICE ⊆ NP \ coNP . For the other direction, if L is in NP \coNP , then there is one NP machine M1(x; y) solving L, and another NP machine M2(x; z) solving coL. We can therefore de¯ne a new machine that guesses the guess y for M1, and the guess z for M2. -

Glossary of Complexity Classes

App endix A Glossary of Complexity Classes Summary This glossary includes selfcontained denitions of most complexity classes mentioned in the b o ok Needless to say the glossary oers a very minimal discussion of these classes and the reader is re ferred to the main text for further discussion The items are organized by topics rather than by alphab etic order Sp ecically the glossary is partitioned into two parts dealing separately with complexity classes that are dened in terms of algorithms and their resources ie time and space complexity of Turing machines and complexity classes de ned in terms of nonuniform circuits and referring to their size and depth The algorithmic classes include timecomplexity based classes such as P NP coNP BPP RP coRP PH E EXP and NEXP and the space complexity classes L NL RL and P S P AC E The non k uniform classes include the circuit classes P p oly as well as NC and k AC Denitions and basic results regarding many other complexity classes are available at the constantly evolving Complexity Zoo A Preliminaries Complexity classes are sets of computational problems where each class contains problems that can b e solved with sp ecic computational resources To dene a complexity class one sp ecies a mo del of computation a complexity measure like time or space which is always measured as a function of the input length and a b ound on the complexity of problems in the class We follow the tradition of fo cusing on decision problems but refer to these problems using the terminology of promise problems -

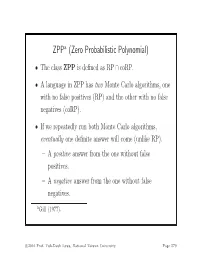

ZPP (Zero Probabilistic Polynomial)

ZPPa (Zero Probabilistic Polynomial) • The class ZPP is defined as RP ∩ coRP. • A language in ZPP has two Monte Carlo algorithms, one with no false positives (RP) and the other with no false negatives (coRP). • If we repeatedly run both Monte Carlo algorithms, eventually one definite answer will come (unlike RP). – A positive answer from the one without false positives. – A negative answer from the one without false negatives. aGill (1977). c 2016 Prof. Yuh-Dauh Lyuu, National Taiwan University Page 579 The ZPP Algorithm (Las Vegas) 1: {Suppose L ∈ ZPP.} 2: {N1 has no false positives, and N2 has no false negatives.} 3: while true do 4: if N1(x)=“yes”then 5: return “yes”; 6: end if 7: if N2(x) = “no” then 8: return “no”; 9: end if 10: end while c 2016 Prof. Yuh-Dauh Lyuu, National Taiwan University Page 580 ZPP (concluded) • The expected running time for the correct answer to emerge is polynomial. – The probability that a run of the 2 algorithms does not generate a definite answer is 0.5 (why?). – Let p(n) be the running time of each run of the while-loop. – The expected running time for a definite answer is ∞ 0.5iip(n)=2p(n). i=1 • Essentially, ZPP is the class of problems that can be solved, without errors, in expected polynomial time. c 2016 Prof. Yuh-Dauh Lyuu, National Taiwan University Page 581 Large Deviations • Suppose you have a biased coin. • One side has probability 0.5+ to appear and the other 0.5 − ,forsome0<<0.5. -

The Weakness of CTC Qubits and the Power of Approximate Counting

The weakness of CTC qubits and the power of approximate counting Ryan O'Donnell∗ A. C. Cem Sayy April 7, 2015 Abstract We present results in structural complexity theory concerned with the following interre- lated topics: computation with postselection/restarting, closed timelike curves (CTCs), and approximate counting. The first result is a new characterization of the lesser known complexity class BPPpath in terms of more familiar concepts. Precisely, BPPpath is the class of problems that can be efficiently solved with a nonadaptive oracle for the Approximate Counting problem. Similarly, PP equals the class of problems that can be solved efficiently with nonadaptive queries for the related Approximate Difference problem. Another result is concerned with the compu- tational power conferred by CTCs; or equivalently, the computational complexity of finding stationary distributions for quantum channels. Using the above-mentioned characterization of PP, we show that any poly(n)-time quantum computation using a CTC of O(log n) qubits may as well just use a CTC of 1 classical bit. This result essentially amounts to showing that one can find a stationary distribution for a poly(n)-dimensional quantum channel in PP. ∗Department of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University. Work performed while the author was at the Bo˘gazi¸ciUniversity Computer Engineering Department, supported by Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship project number 626373. yBo˘gazi¸ciUniversity Computer Engineering Department. 1 Introduction It is well known that studying \non-realistic" augmentations of computational models can shed a great deal of light on the power of more standard models. The study of nondeterminism and the study of relativization (i.e., oracle computation) are famous examples of this phenomenon. -

The Computational Complexity Column by V

The Computational Complexity Column by V. Arvind Institute of Mathematical Sciences, CIT Campus, Taramani Chennai 600113, India [email protected] http://www.imsc.res.in/~arvind The mid-1960’s to the early 1980’s marked the early epoch in the field of com- putational complexity. Several ideas and research directions which shaped the field at that time originated in recursive function theory. Some of these made a lasting impact and still have interesting open questions. The notion of lowness for complexity classes is a prominent example. Uwe Schöning was the first to study lowness for complexity classes and proved some striking results. The present article by Johannes Köbler and Jacobo Torán, written on the occasion of Uwe Schöning’s soon-to-come 60th birthday, is a nice introductory survey on this intriguing topic. It explains how lowness gives a unifying perspective on many complexity results, especially about problems that are of intermediate complexity. The survey also points to the several questions that still remain open. Lowness results: the next generation Johannes Köbler Humboldt Universität zu Berlin [email protected] Jacobo Torán Universität Ulm [email protected] Abstract Our colleague and friend Uwe Schöning, who has helped to shape the area of Complexity Theory in many decisive ways is turning 60 this year. As a little birthday present we survey in this column some of the newer results related with the concept of lowness, an idea that Uwe translated from the area of Recursion Theory in the early eighties. Originally this concept was applied to the complexity classes in the polynomial time hierarchy. -

Quantum Computational Complexity Theory Is to Un- Derstand the Implications of Quantum Physics to Computational Complexity Theory

Quantum Computational Complexity John Watrous Institute for Quantum Computing and School of Computer Science University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. Article outline I. Definition of the subject and its importance II. Introduction III. The quantum circuit model IV. Polynomial-time quantum computations V. Quantum proofs VI. Quantum interactive proof systems VII. Other selected notions in quantum complexity VIII. Future directions IX. References Glossary Quantum circuit. A quantum circuit is an acyclic network of quantum gates connected by wires: the gates represent quantum operations and the wires represent the qubits on which these operations are performed. The quantum circuit model is the most commonly studied model of quantum computation. Quantum complexity class. A quantum complexity class is a collection of computational problems that are solvable by a cho- sen quantum computational model that obeys certain resource constraints. For example, BQP is the quantum complexity class of all decision problems that can be solved in polynomial time by a arXiv:0804.3401v1 [quant-ph] 21 Apr 2008 quantum computer. Quantum proof. A quantum proof is a quantum state that plays the role of a witness or certificate to a quan- tum computer that runs a verification procedure. The quantum complexity class QMA is defined by this notion: it includes all decision problems whose yes-instances are efficiently verifiable by means of quantum proofs. Quantum interactive proof system. A quantum interactive proof system is an interaction between a verifier and one or more provers, involving the processing and exchange of quantum information, whereby the provers attempt to convince the verifier of the answer to some computational problem. -

Some NP-Complete Problems

Appendix A Some NP-Complete Problems To ask the hard question is simple. But what does it mean? What are we going to do? W.H. Auden In this appendix we present a brief list of NP-complete problems; we restrict ourselves to problems which either were mentioned before or are closely re- lated to subjects treated in the book. A much more extensive list can be found in Garey and Johnson [GarJo79]. Chinese postman (cf. Sect. 14.5) Let G =(V,A,E) be a mixed graph, where A is the set of directed edges and E the set of undirected edges of G. Moreover, let w be a nonnegative length function on A ∪ E,andc be a positive number. Does there exist a cycle of length at most c in G which contains each edge at least once and which uses the edges in A according to their given orientation? This problem was shown to be NP-complete by Papadimitriou [Pap76], even when G is a planar graph with maximal degree 3 and w(e) = 1 for all edges e. However, it is polynomial for graphs and digraphs; that is, if either A = ∅ or E = ∅. See Theorem 14.5.4 and Exercise 14.5.6. Chromatic index (cf. Sect. 9.3) Let G be a graph. Is it possible to color the edges of G with k colors, that is, does χ(G) ≤ k hold? Holyer [Hol81] proved that this problem is NP-complete for each k ≥ 3; this holds even for the special case where k =3 and G is 3-regular.