Why Is the Giant Panda Black and White?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Reproductive PATTERNS and Human-INFLUENCED Z]`Ynagj Af Zjgof Z]Yjk& Aehda[Ylagfk ^Gj the Conservation of LARGE Carnivores](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6785/reproductive-patterns-and-human-influenced-z-ynagj-af-zjgof-z-yjk-aehda-ylagfk-gj-the-conservation-of-large-carnivores-436785.webp)

Reproductive PATTERNS and Human-INFLUENCED Z]`Ynagj Af Zjgof Z]Yjk& Aehda[Ylagfk ^Gj the Conservation of LARGE Carnivores

P Natural and Department Ecology of Resource Management Fgjo]_aYfMfan]jkalqg^Da^]K[a]f[]kMfan]jkal]l]l^gjeadb¬ hilosophiae Doctor <]hYjlYe]flg\]:ag\an]jka\Y\q?]klaf9eZa]flYd& Universidad de León E-24071 León, Spain. www.unileon.es Reproductive patterns and human-influenced ( P Z]`YnagjafZjgofZ]Yjk&Aehda[Ylagfk^gj h D) the conservation of large carnivores. Thesis 2010:01 Thesis J]hjg\mckbgfke¬fkl]jg_e]ff]kc]kcYhlYl^]j\k]f\jaf_`gkZjmfZb¬jf& Cgfk]cn]fk]j^gjZ]nYjaf_]fYnklgj]jgn\qj& Andrés Ordiz %g_Zagnal]fkcYh Reproductive patterns and human-influenced behavior in brown bears Implications for the conservation of large carnivores Reproduksjonsmønster og menneskeskapt atferdsendring hos brunbjørn Konsekvenser for bevaringen av store rovdyr Philosophiae Doctor (PhD) Thesis Andrés Ordiz Dept. of Ecology and Natural Resource Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences & Dept. de Biodiversidad y Gestión Ambiental Universidad de León Ås/León 2010 UMB Thesis number 2010: 01 ISSN 1503-1667 ISBN 978-82-575-0913-2 This thesis has been conducted as a PhD research co-supervision agreement between the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and the University of León (Spain). I acknowledge the effort of J. E. Swenson, E. de Luis Calabuig and E. Panero to succeed in establishing the agreement. PhD supervisors Prof. Jon E. Swenson (main supervisor) Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences Pb. 5003, 1432 Ås, Norway Dr. Ole-Gunnar Støen Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences Pb. 5003, 1432 Ås, Norway Prof. Miguel Delibes de Castro Estación Biológica de Doñana, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Avenida Américo Vespucio s/n Isla de la Cartuja E-41092 Sevilla, Spain Adjudication committee Prof. -

Museum of Natural History

p m r- r-' ME FYF-11 - - T r r.- 1. 4,6*. of the FLORIDA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY THE COMPARATIVE ECOLOGY OF BOBCAT, BLACK BEAR, AND FLORIDA PANTHER IN SOUTH FLORIDA David Steffen Maehr Volume 40, No. 1, pf 1-176 1997 == 46 1ms 34 i " 4 '· 0?1~ I. Al' Ai: *'%, R' I.' I / Em/-.Ail-%- .1/9" . -_____- UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY am published at irregular intervals Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. JOHN F. EISENBERG, EDITOR RICHARD FRANZ CO-EDIWR RHODA J. BRYANT, A£ANAGING EMOR Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manuscripts should be addressed to: Managing Editor. Bulletin; Florida Museum of Natural Histoty, University of Florida P. O. Box 117800, Gainesville FL 32611-7800; US.A This journal is printed on recycled paper. ISSN: 0071-6154 CODEN: BF 5BAS Publication date: October 1, 1997 Price: $ 10.00 Frontispiece: Female Florida panther #32 treed by hounds in a laurel oak at the site of her first capture on the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge in central Collier County, 3 February 1989. Photograph by David S. Maehr. THE COMPARATIVE ECOLOGY OF BOBCAT, BLACK BEAR, AND FLORIDA PANTHER IN SOUTH FLORIDA David Steffen Maehri ABSTRACT Comparisons of food habits, habitat use, and movements revealed a low probability for competitive interactions among bobcat (Lynx ndia). Florida panther (Puma concotor cooi 1 and black bear (Urns amencanus) in South Florida. All three species preferred upland forests but ©onsumed different foods and utilized the landscape in ways that resulted in ecological separation. -

Giant Panda Facts (Ailuropoda Melanoleuca)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Giant Panda Facts (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Giant panda. John J. Mosesso What animal is black and white Giant pandas are bears with one or two cubs weighing 3 to 5 and loved all over the world? If you striking black and white markings. ounces each is born in a sheltered guessed the giant panda, you’re The ears, eye patches, legs and den. Usually only one cub survives. right! shoulder band are black; the rest The eyes open at 1 1/2 to 2 months of the body is whitish. They have and the cub becomes mobile at The giant panda is also known as thick, woolly coats to insulate them approximately three months of the panda bear, bamboo bear, or in from the cold. Adults are four to six age. At 12 months the cub becomes Chinese as Daxiongmao, the “large feet long and may weigh up to 350 totally independent. While their bear cat.” In fact, its scientific pounds—about the same size as average life span in the wild is name means “black and white cat- the American black bear. However, about 15 years, giant pandas in footed animal.” unlike the black bear, giant pandas captivity have been known to live do not hibernate and cannot walk well into their twenties. Giant pandas are found only in on their hind legs. the mountains of central China— Scientists have debated for more in small isolated areas of the The giant panda has unique front than a century whether giant north and central portions of the paws—one of the wrist bones is pandas belong to the bear family, Sichuan Province, in the mountains enlarged and elongated and is used the raccoon family, or a separate bordering the southernmost part of like a thumb, enabling the giant family of their own. -

Project Learning Tree Life on the Edge Activity

PLT PreK8_Act76-96–FRZ 11/1/05 2:33 PM Page 385 StudentPage Life on the Edge Endangered Species – anative species or subspecies that is in serious danger of becoming extinct throughoutall,or a significantportion, of its range as a result of one or more causes,including loss of habitat, overexploitation,competition, or disease. Threatened Species – anative species that,while not presently threatened with extinction, is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future if not given special protection and management efforts. Rare Species – anative species that, although not presently threatened with extinction, exists in such small numbers throughoutits range thatitmay become threatened if its presentenvironmental conditions worsen. Species Name: 1. What is its status? (See above.) 6. Why is it rare,threatened, or endangered? 2. Wheredoes it live? 7. Areanycurrentactions being taken to improve its chances of survival? 3. Whatdoes it look like? 8. What are some ways in which people can reduce or eliminate the threats to the survival of the species? 4. Whatis its habitat? 9. What other species depend on it? 5. Whatis the currentrange of its population? 10. Whyis it importantthatthis species sur- vive? (Giveseveral reasons.) Activity 88 • Life on the Edge Project Learning Tree • PreK–8Activity Guide ©American Forest Foundation 385 PLT PreK8_Act76-96–FRZ 11/1/05 2:33 PM Page 386 StudentPage Some Endangered Species Giant Panda Bengal Tiger Pandas live in the Himalayan range of central Asia, Lurking in the forests and mangrove swamps of India, generally ataltitudes between 5,000 and 10,000 feet Myanmar,Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Nepal, the 500- (1,524 and 3,048 meters). -

Featuring Polar Bears, Giant Pandas, Brown Bears and Many More All You N

Spring 2018 brilliantbrilliantAllAll youyou needneed toto knowknow aboutaboutbears!bears! thethe bearbear family!family! FeaturingFeaturing polarpolar bears,bears, giantgiant pandas,pandas, brownbrown bearsbears andand manymany moremore wInwIn AnImal goodIes In our colourIng competItIon! Plus pawsome puzzles, furry facts, jokes wIth real bIte Spring 2018 brilliantAll you need to know aboutbears! the bear family! brilliantAll you need to know aboutbears! the bear family! FeaturingFeaturing polarpolar bears,bears, giantgiant pandas,pandas, brownbrown bearsbears andand manymany moremore wInwIn AnImal goodIes In our colourIng competItIon! Plus pawsome puzzles, furry facts, jokes wIth real bIte Spring 2018 brilliantbrilliantAllAll youyou needneed toto knowknow aboutaboutbears!bears! thethe bearbear family!family! FeaturingFeaturing polarpolar bears,bears, giantgiant pandas,pandas, brownbrown bearsbears andand manymany moremore wInwIn AnImal goodIes In our colourIng competItIon! Plus pawsome puzzles, furry facts, jokes wIth real bIte Spring 2018 brilliantbrilliantAllAll youyou needneed toto knowknow aboutaboutbears!bears! thethe bearbear family!family! FeaturingFeaturing polarpolar bears,bears, giantgiant pandas,pandas, brownbrown bearsbears andand manymany moremore wInwIn AnImal goodIes In our colourIng competItIon! Plus pawsome puzzles, furry facts, jokes wIth real bIte MEETMEET THETHE BEARSBEARS LITTLE This issue of Wild About Explorers is all about bears! Discover their Brown bear Giant panda Asian and LARGE favourite foods, find out why they sleep for months at a time, and meet LIVES: Across Europe, LIVES: Forests in China the bears that live in some of the coldest places on Earth. North America and Asia black bear The smallest ABOUT ME: I am easily Bears are found in many parts of the world, including Europe, America, LIVES: Forests in member of the ABOUT ME: I have recognised by my black South and East Asia bear family is Asia and the Arctic. -

Pan 1 Recent Advances in Elucidating the Function of Zebra Stripes

Pan 1 Recent Advances in Elucidating the Function of Zebra Stripes: Parasite Avoidance and Thermoregulation Do Not Resolve the Mystery Introduction Why are zebras striped? This question has baffled biologists for ages since the time of Darwin (Darwin 545). Although we remain far from an answer, past research was not done in vain. Currently, as much as 18 different theories have been proposed (Horváth et al. “EETSDNCZ” 1). These proposed explanations largely fall into four categories: 1) Predator avoidance through crypsis and various types of visual confusion (Ruxton 238), 2) reinforcement of social interactions (239), 3) ectoparasite deterrence (241), and 4) thermoregulation (239). Among the four groups of hypotheses, only the latter two have gained some support. The speculations that stripes help zebras blend in with tall grass (238), appear larger when in a group (237), or dazzle vertebrate predators like lions or spotted hyenas (238) were all but rejected because of the lack of empirical support and not because of the lack of trying (Caro et al. “TFOZS” 3; Larison et al. “HTZGIS” 3; Ruxton 238). Similarly, the idea that zebra stripes provide social benefits such as individual identification and bonding remains largely speculative (Ruxton 240), if not just outright rejected (Caro et al. “TFOZS” 3). Many of the hypotheses also do not actually suggest a fitness benefit but explain how the zebras interact (Ruxton 239). Therefore, they insufficiently explain why zebra stripes evolved in the first place. In contrast, overwhelming empirical evidence support the hypothesis that ‘zebra like’ stripes deter ectoparasites like glossinids and tabanids (Blaho et al. -

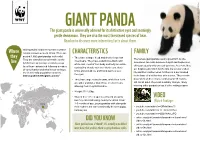

GIANT PANDA the Giant Panda Is Universally Admired for Its Distinctive Eyes and Seemingly Gentle Demeanour

© naturepl.com / Edwin Giesbers WWF GIANT PANDA The giant panda is universally admired for its distinctive eyes and seemingly gentle demeanour. They are also the most threatened species of bear. Read on to discover more interesting facts about them. Giant pandas inhabit temperate montane Where forests in south-western China. There are CHARACTERISTICS FAMILY they around 1,860 giant pandas in the wild. • They have a larger head and shorter legs than The female giant panda usually gives birth to one, They are classified as vulnerable on the most bears. They have a distinctive black and live sometimes two cubs between August and September, IUCN Red List having recently been up white coat, most of their body and belly are white, although usually only one cub survives. As a cub, they listed from endangered following decades contrasting sharply with their black ears, black k ' are helpless after birth for the first few weeks of their of conservation wor that s now seeing a limbs and shoulders, and black patches over rise in their wild population numbers. life and their mother cares for them in a den located the eyes. wwf.org.uk/wildlife/giant_panda/ in the base of a hollow tree or in a cave. They remain • They have large muscular jaws, while their teeth dependent on their mother until around 18 months are wider and flatter than those of other bears, old. As an adult, they lead a solitary lifestyle, rarely allowing them to grind bamboo. meeting other pandas unless it’s the mating season. • Weight: 75-125kg. • Most of their time is spent eating and sleeping, VIDEO but they can climb using muscly forearms. -

How Is the COVID-19 Outbreak Affecting Wildlife Around the World?

Open Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10, 497-517 https://www.scirp.org/journal/oje ISSN Online: 2162-1993 ISSN Print: 2162-1985 How Is the COVID-19 Outbreak Affecting Wildlife around the World? Abdel Fattah N. Abd Rabou Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine How to cite this paper: Abd Rabou, A.N. Abstract (2020) How Is the COVID-19 Outbreak Affecting Wildlife around the World? Open The COVID-19 is the infectious disease caused by the most recently discov- Journal of Ecology, 10, 497-517. ered coronavirus at an animal market in Wuhan, China. Many wildlife spe- https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2020.108032 cies have been suggested as possible intermediate sources for the transmission Received: June 2, 2020 of COVID-19 virus from bats to humans. The quick transmission of COVID-19 Accepted: August 1, 2020 outbreak has imposed quarantine measures across the world, and as a result, Published: August 4, 2020 most of the world’s towns and cities fell silent under lockdowns. The current Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and study comes to investigate the ways by which the COVID-19 outbreak affects Scientific Research Publishing Inc. wildlife globally. Hundreds of internet sites and scientific reports have been This work is licensed under the Creative reviewed to satisfy the needs of the study. Stories of seeing wild animals Commons Attribution International roaming the quiet, deserted streets and cities during the COVID-19 outbreak License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ have been posted in the media and social media. -

China the Giant Panda

China — The Giant Panda China The Giant Panda Deep in a forest, a black-and-white bear sits peacefully. It chews the green leaves of a plant. The bear is alone, but there are others not too far away. Later, it might amble over to find them. They may play together. This is the giant panda in nature. The giant panda is a bear native to China. It is unusual for a bear to be found only in one place. For over a hundred years, scientists thought that giant pandas might belong to the raccoon family. Then research in the 1980s showed that giant pandas are bears after all. These bears are black and white, with black patches of fur around their eyes. Giant pandas live in bamboo forests, high in the mountains in the western part of China. This is their habitat. Here they eat bamboo. Bamboo is a grass that can grow 100 feet high. It has hollow green stalks.1 Giant pandas peel off the leaves and stems to eat. Their paws are well adapted to this task. They have a special thumb that helps them grasp the bamboo. Giant pandas spend about 10-15 hours a day eating this plant. Giant pandas are an endangered species.2 Based on a survey completed in the mid-1980s, researchers determined there were only 1,000 giant pandas left in the wild. This was the lowest number ever recorded. One reason the population of giant pandas had declined is that they had less bamboo to eat. A lot of the bamboo forests where giant pandas lived had been wiped out by logging. -

Benefits of Zebra Stripes: Behaviour of Tabanid Flies Around Zebras and Horses

Caro, T. , Argueta, Y., Briolat, E., Bruggink, J., Kasprowsky, M., Lake, J., Mitchell, M., Richardson, S., & How, M. (2019). Benefits of zebra stripes: behaviour of tabanid flies around zebras and horses. PLoS ONE, 14(2), [e0210831]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210831 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.1371/journal.pone.0210831 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via PLoS at DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210831. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ RESEARCH ARTICLE Benefits of zebra stripes: Behaviour of tabanid flies around zebras and horses 1 1 2 3 Tim CaroID *, Yvette Argueta , Emmanuelle Sophie Briolat , Joren Bruggink , 2 4 2 2 Maurice Kasprowsky , Jai Lake , Matthew J. Mitchell , Sarah RichardsonID , 4 Martin HowID 1 Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, University of California Davis, Davis, California, United States of America, 2 Centre for Ecology and Conservation Biosciences, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall, United Kingdom, 3 Aeres University of Applied Sciences, Almere, Netherlands, 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom * [email protected] a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Averting attack by biting flies is increasingly regarded as the evolutionary driver of zebra a1111111111 stripes, although the precise mechanism by which stripes ameliorate attack by ectoparasites a1111111111 is unknown. -

Factsheet Giant Panda

Giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) The giant panda, the rarest of bear species, is found in mountainous areas in China. They mainly live on the east side of the Tibetan Plateau. Origin The giant panda is classified under the subfamily of Ailuropodinae and is the only existing representative of this family. Two subspecies have been recognized, Ailuropoda melanoleuca melanoleuca and Ailuropoda melanoleuca qinlingensis, or the small panda (also red panda) and the giant panda. The classification of the giant panda has been the subject of some debate: a diet consisting of bamboo, ambiguity as regards their ancestors and different anatomic characteristics all gave rise to uncertainty within the scientific community on whether the giant panda was indeed a true bear. Genetic research suggests that the panda is a real bear and therefore part of the Ursidae family. However, some doubt will always remain and a few experts believe that the giant panda and the small panda form a separate family altogether. Others disagree completely and believe that the panda is not a true bear but related to the raccoon. Opinions differ greatly on this subject. One could say that the small panda is indeed related to the raccoon and their relatives. Habitat The giant panda is found only in the impenetrable bamboo forests in the mountains at an elevation of 1,400 to 4,000 meter. Appearance The giant panda is very recognizable by its distinct black and white coloration. They have black patches around the eyes, making the eyes look unusually big. Another, less conspicuous, characteristic is the existence of a sixth finger: the panda has six fingers on the forelimbs instead of five. -

Giant Panda Policy Questions & Answers

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Giant Panda Policy Questions & Answers Why have a policy just for pandas? Giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) are protected by the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Any import requires the Fish and Wildlife Service to issue a permit under these wildlife measures. The giant panda is unique. It is highly endangered, with an estimated population of 1,600 animals in the wild, extremely popular with the public worldwide, and capable of generating substantial revenue when displayed. Because of this, giant panda imports have had a controversial history. Conservationists fear humans will “love the panda to death.” What does the policy cover? The policy clarifies the information considered in making permit findings under CITES and the ESA, and assists Chris Wilkinson CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 persons in filing a complete application for panda import, export, re-export, take, enhances the sustainability of the research, if related to captive or interstate or foreign commerce. The captive population, and contributes breeding, supplements China’s policy also provides guidance to assist to the recovery of pandas in the wild. conservation program to achieve a Service decision-makers and staff in The Service will consider whether the self-sustaining captive population reviewing panda permit applications to application: ensure that permit issuance criteria have • Describes the origin of the pandas to been addressed. The policy discusses • Outlines how net profits will be be imported and clearly shows that the purposes for which a permit may be calculated and fund disbursement the requested activity did not and issued and when exhibition of pandas is will be monitored, and has a provision will not cause the removal of animals allowed.