BASINGSTOKE CANAL Introduction the First Canal in England Was The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overton Village Design Statement

OVERTON DS 2/2/02 12:47 PM Page 1 OvertonOverton Village Design Statement A.D. 2002 OVERTON DS 2/2/02 12:47 PM Page 2 CONTENTS 3 Introduction What the VDS is – aims and objectives 4 The Village Context Geographical and historical aspects Community aspects Overton Mill Affordable housing Community guidelines Business and employment Entering the village from Basingstoke down Overton Hill Business guidelines 8 Landscape and Environment The visual character of the surrounding landscape Areas of special designation Landscape and environment design guidelines 14 Settlement and Transport Patterns Village settlement patterns Transport patterns and character of streets and routes through the village Winchester Street Settlement and transport guidelines 17 Open Spaces within the Village Character and pattern of open spaces within the village Recreational facilities The Test Valley. Access to the River Test Open spaces guidelines 20 The Built Environment Areas of distinctive building types Sizes, styles and types of buildings Sustainability and environmental issues Built Environment guidelines Town Mill, converted and extended to provide retirement flats 24 Other Features Walls and plot boundaries, trees, street furniture, rights of way, light pollution, ‘green tunnels’, overhead lines, shop fronts. Guidelines 27 What the children say 28 References and acknowledgements Cover picture: flying north over our village in 2001 Leaving the village by the B 3400 at Southington Unediited comments lliifted from the questiionnaiires...... “The ffeelliing tthatt Overtton has – tthe reall villllage communitty..” 2 OVERTON DS 2/2/02 12:47 PM Page 3 INTRODUCTION What is the Village Design Statement? Overton’s Village Design Statement is a document which aims to record the characteristics, natural and man made, which are seen by the local community Guidelines relate to large and small, old as contributing to the area’s and new distinctiveness. -

A Beginner's Guide to Boating on Inland Waterways

Ti r A Beginner’s Guide To Boating On Inland Waterways Take to the water with British Waterways and the National Rivers Authority With well over 4,000 km (2,500 miles) of rivers and canals to explore, from the south west of England up to Scotland, our inland waterways offer plenty of variety for both the casual boater and the dedicated enthusiast. If you have ever experienced the pleasures of 'messing about on boats', you will know what a wealth of scenery and heritage inland waterways open up to us, and the unique perspective they provide. Boating is fun and easy. This pack is designed to help you get afloat if you are thinking about buying a boat. Amongst other useful information, it includes details of: Navigation Authorities British Waterways (BW) and the National Rivers Authority (NRA), which is to become part of the new Environment Agency for England and Wales on 1 April 1996, manage most of our navigable rivers and canals. We are responsible for maintaining the waterways and locks, providing services for boaters and we licence and manage boats. There are more than 20 smaller navigation authorities across the country. We have included information on some of these smaller organisations. Licences and Moorings We tell you everything you need to know from, how to apply for a licence to how to find a permanent mooring or simply a place for «* ^ V.’j provide some useful hints on buying a boat, includi r, ...V; 'r 1 builders, loans, insurance and the Boat Safety Sch:: EKVIRONMENT AGENCY Useful addresses A detailed list of useful organisations and contacts :: : n a t io n a l libra ry'& ■ suggested some books we think will help you get t information service Happy boating! s o u t h e r n r e g i o n Guildbourne House, Chatsworth Road, W orthing, West Sussex BN 11 1LD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 1 Owning a Boat Buying a Boat With such a vast.range of boats available to suit every price range, . -

Low Bridge, Everybody Down' (WITH INDEX)

“Low Bridge; Everybody Down!” Notes & Notions on the Construction & Early Operation of the Erie Canal Chuck Friday Editor and Commentator 2005 “Low Bridge; Everybody Down!” 1 Table of Contents TOPIC PAGE Introduction ………………………………………………………………….. 3 The Erie Canal as a Federal Project………………………………………….. 3 New York State Seizes the Initiative………………………………………… 4 Biographical Sketch of Jesse Hawley - Early Erie Canal Advocate…………. 5 Western Terminus for the Erie Canal (Black Rock vs Buffalo)……………… 6 Digging the Ditch……………………………………………………………. 7 Yankee Ingenuity…………………………………………………………….. 10 Eastward to Albany…………………………………………………………… 12 Westward to Lake Erie………………………………………………………… 16 Tying Up Loose Ends………………………………………………………… 20 The Building of a Harbor at Buffalo………………………………………….. 21 Canal Workforce……………………………………………………………… 22 The Irish Worker Story……………………………………………………….. 27 Engineering Characteristics of Canals………………………………………… 29 Early Life on the Canal……………………………………………………….. 33 Winter – The Canal‘sGreatest Impediment……………………………………. 43 Canal Expansion………………………………………………………………. 45 “Low Bridge; Everybody Down!” 2 ―Low Bridge; Everybody Down!‖ Notes & Notions on the Construction & Early Operation of the Erie Canal Initial Resource Book: Dan Murphy, The Erie Canal: The Ditch That Opened A Nation, 2001 Introduction A foolhardy proposal, years of political bickering and partisan infighting, an outrageous $7.5 million price tag (an amount roughly equal to about $4 billion today) – all that for a four foot deep, 40 foot wide ditch connecting Lake Erie in western New York with the Hudson River in Albany. It took 7 years of labor, slowly clawing shovels of earth from the ground in a 363-mile trek across the wilderness of New York State. Through the use of many references, this paper attempts to describe this remarkable construction project. Additionally, it describes the early operation of the canal and its impact on the daily life on or near the canal‘s winding path across the state. -

Frensham Parish Council

Frensham Parish Council Village Design Statement Contents 1. What is a VDS? 2. Introduction & History 3. Open Spaces & Landscape 4. Buildings – Style & Detail 5. Highways & Byways 6. Sports & rural Pursuits Summary Guidelines & Action Points Double page spread of parish map in the centre of document Appendix: Listed Buildings & Artefacts in Parish 1 What is a Village Design Statement? A Village Design Statement (VDS) highlights the qualities, style, building materials, characteristics and landscape setting of a parish, which are valued by its residents. The background, advice and guidelines given herein should be taken into account by developers, builders and residents before considering development. The development policies for the Frensham Parish area are the “saved Policies” derived from Waverley Borough Council’s Local Plan 2002, (which has now been superseded. It is proposed that the Frensham VDS should be Supplementary Planning Guidance, related to Saved Policy D4 ‘Design and Layout’. Over recent years the Parish Council Planning Committee, seeing very many applications relating to our special area, came to the conclusion that our area has individual and special aspirations that we wish to see incorporated into the planning system. Hopefully this will make the Parish’s aspirations clearer to those submitting applications to the Borough Council and give clear policy guidance. This document cannot be exhaustive but we hope that we have included sufficient detail to indicate what we would like to conserve in our village, and how we would like to see it develop. This VDS is a ‘snapshot’ reflecting the Parish’s views and situation in2008, and may need to be reviewed in the future in line with changing local needs, and new Waverley, regional and national plans and policies. -

The Mill House, Sherborne St John, Hampshire RG24 9HU

THE MILL HOUSE, SHERBORNE ST JOHN GUIDE PRICE £850,000 FREEHOLD The Mill House, Sherborne St John, Hampshire RG24 9HU No.1 & 2 The Mill House currently a pair of semi detached properties being offered for sale as one. Detached Farmhouse 2 Receptions 2 Kitchens 2 Bathrooms 5 Bedrooms Open Countryside Views 7.58 Acres Outside The Mill House is accessed down a private driveway with public footpath and will be found at the bottom of the lane on the right. The property will benefit from both gardens of no.1 & no.2. The property extends to 7.58 acres including 4 acres paddock, Mill Pond and stream and auxiliary outbuildings. Guide Price £850,000 Freehold ACCOMMODATION The current accommodation for no.1 Mill House comprises entrance porch to hallway with tiled flooring. Sitting room with open fireplace and tiled flooring. Kitchen/breakfast room with inset space for cooker, sink and drainer and a range of eye and base level units with worktops. Separate utility/laundry room. On the first floor there are 3 bedrooms and family bathroom. The current accommodation for no.2 Mill House comprises hallway, living room with fireplace and inset log burner. Refitted kitchen with electric hob and oven and grill below, inset sink and drainer, larder. Rear lobby with access to separate utility/laundry room. First floor has 2 bedrooms and family bathroom. PLANNING The property is presently 2 dwellings but it is believed that it could be suitable for a conversion back to a single dwelling, subject to planning. FOR VIEWINGS Bring suitable outdoor footwear i.e.Wellingtons Location No's 1 & 2 The Mill House are situated in the pretty Hampshire village of Sherborne St. -

Download Brochure

WELCOME to BROADOAKS PAR K — Inspirational homes for An exclusive development of luxurious Built by Ernest Seth-Smith, the striking aspirational lifestyles homes by award winning housebuilders Broadoaks Manor will create the Octagon Developments, Broadoaks Park centrepiece of Broadoaks Park. offers the best of countryside living in Descending from a long-distinguished the heart of West Byfleet, coupled with line of Scottish architects responsible for excellent connections into London. building large areas of Belgravia, from Spread across 25 acres, the gated parkland Eaton Square to Wilton Crescent, Seth-Smith estate offers a mixture of stunning homes designed the mansion and grounds as the ranging from new build 2 bedroom ultimate country retreat. The surrounding apartments and 3 - 6 bedroom houses, lodges and summer houses were added to beautifully restored and converted later over the following 40 years, adding apartments and a mansion house. further gravitas and character to the site. Surrey LIVING at its BEST — Painshill Park, Cobham 18th-century landscaped garden with follies, grottoes, waterwheel and vineyard, plus tearoom. Experience the best of Surrey living at Providing all the necessities, a Waitrose Retail therapy Broadoaks Park, with an excellent range of is located in the village centre, and Guildford’s cobbled High Street is brimming with department stores restaurants, parks and shopping experiences for a wider selection of shops, Woking and and independent boutiques alike, on your doorstep. Guildford town centres are a short drive away. offering one of the best shopping experiences in Surrey. Home to artisan bakeries, fine dining restaurants Opportunities to explore the outdoors are and cosy pubs, West Byfleet offers plenty plentiful, with the idyllic waterways of the of dining with options for all occasions. -

2011-03-15 Item 6 Cptl Prg Tbl 3 HR HAT (HF000001492519)

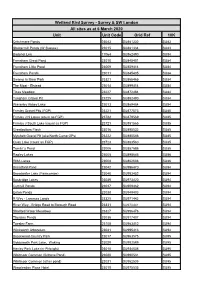

ITEM 6 Table 3 Planned Maintenance Programme (Operation Resilience) 2011/12 Hart Carriageway Resurfacing Road/Location Parish/Ward From To Timing/Status A327 Minley Road Blackwater & Hawley A30 roundabout B3013 roundabout Quarter 2 New Road Church Crookham Jct Gordon Avenue Jct Pine Grove Quarter 2 Sandy Lane Church Crookham Manor Court Beacon Hill Road Quarter 2 A323 Reading Road South (nr. Canal) Fleet Jct Clarence Road Jct Aldershot Road Quarter 2 Albert St. (jct with Upper Street) Fleet Jct Upper Street o/s 105 Quarter 2 Crookham Road Fleet Jct Reading Road North Jct St James Road Quarter 2 Regent Close Fleet Whole cul-de-sac Whole cul-de-sac Quarter 2 Velmead Road Fleet Jct Norris Hill Road Jct Fairland Close Quarter 2 Hazeley Close (B3011 bellmouth) Hartley Wintney B3011 bellmouth Bellmouth only Quarter 2-3 A30 London Road Hook Jct Old Reading Road Station Road roundabout Quarter 2-3 Holt Lane Hook Jct London Road Jct Great Marlow Quarter 2-3 Pantile Drive Hook Jct Holt Way Jct Holt Lane Quarter 2-3 A287 Broad Oak roundabout & offslip Odiham Roundabout and offslip Roundabout and offslip Quarter 2-3 B3272 Reading Road Yateley 60m west of jct Moulsham Lane 60m East of jct The Link Quarter 2-3 Monteagle Lane (1) Yateley Poets Corner Wordsworth Avenue Quarter 2-3 Monteagle Lane (2) Yateley Jct Ryves Avenue Jct Throgmorton Road Quarter 2-3 Round Close Yateley Jct Caswell Ride Jct Stevens Hill Quarter 2-3 Ryde Gardens Yateley Jct Firgrove Road End of close Quarter 2-3 10 ITEM 6 Table 3 Drainage Works/Schemes Road/Location Parish/Ward -

Heritage at Risk

Heritage at Risk Contents Introduction Dilapidation in progress History 360 degree view Future Uses Costs and Future Action Report prepared by Altrincham & Bowdon Civic Society June 2020 https://altrinchamandbowdoncs.com/ Introduction Altrincham, Broadheath and Timperley have 48 listed buildings. The Broadheath Canal Warehouse is Grade II listed. It has been allowed to deteriorate to the point where unless remedial action is taken it may become lost for ever. It is our heritage and if we want future generation to understand and be in touch their history, action is required. The Bridgewater Canal was the first contour canals built in the Britain necessitating not a single lock throughout its 39½ mile length. The initial length of the canal, Worsley to Castlefield, was opened in 1761 with permission to build the extension from Stretford to Broadheath allowing that section to open in 1767. The further extension through to Runcorn was opened in 1769 allowing the link up with the Trent and Mersey Canal at Preston Brook. The Duke of Bridgewater had been smart enough to also purchase the land at Broadheath where the turnpike road from Chester to Manchester would cross the canal. Here he established many wharfs along the canal bank to handle goods going into Manchester, principally vegetables from the new market gardens which sprang up around Broadheath. On the return journey the boats brought back coal from the Duke’s mines in Worsley which was used to heat local homes and power small industries. The wharfs at Broadheath handled timber, sand, slates, bricks, limestone to make mortar, raw cotton and flax, and finished good. -

Unit Unit Code Grid Ref 10K Wetland Bird Survey

Wetland Bird Survey - Surrey & SW London All sites as at 6 March 2020 Unit Unit Code Grid Ref 10K Critchmere Ponds 23043 SU881332 SU83 Shottermill Ponds (W Sussex) 23015 SU881334 SU83 Badshot Lea 17064 SU862490 SU84 Frensham Great Pond 23010 SU845401 SU84 Frensham Little Pond 23009 SU859414 SU84 Frensham Ponds 23011 SU845405 SU84 Swamp in Moor Park 23321 SU865465 SU84 The Moat - Elstead 23014 SU899414 SU84 Tices Meadow 23227 SU872484 SU84 Tongham Gravel Pit 23225 SU882490 SU84 Waverley Abbey Lake 23013 SU869454 SU84 Frimley Gravel Pits (FGP) 23221 SU877573 SU85 Frimley J N Lakes (count as FGP) 23722 SU879569 SU85 Frimley J South Lake (count as FGP) 23721 SU881565 SU85 Greatbottom Flash 23016 SU895532 SU85 Mytchett Gravel Pit (aka North Camp GPs) 23222 SU885546 SU85 Quay Lake (count as FGP) 23723 SU883560 SU85 Tomlin`s Pond 23006 SU887586 SU85 Rapley Lakes 23005 SU898646 SU86 RMA Lakes 23008 SU862606 SU86 Broadford Pond 23042 SU996470 SU94 Broadwater Lake (Farncombe) 23040 SU983452 SU94 Busbridge Lakes 23039 SU973420 SU94 Cuttmill Ponds 23037 SU909462 SU94 Enton Ponds 23038 SU949403 SU94 R Wey - Lammas Lands 23325 SU971442 SU94 River Wey - Bridge Road to Borough Road 23331 SU970441 SU94 Shalford Water Meadows 23327 SU996476 SU94 Thursley Ponds 23036 SU917407 SU94 Tuesley Farm 23108 SU963412 SU94 Winkworth Arboretum 23041 SU995413 SU94 Brookwood Country Park 23017 SU963575 SU95 Goldsworth Park Lake, Woking 23029 SU982589 SU95 Henley Park Lake (nr Pirbright) 23018 SU934536 SU95 Whitmoor Common (Brittons Pond) 23020 SU990531 SU95 Whitmoor -

East Woodhay

Information on Rights of Way in Hampshire including extracts from “The Hampshire Definitive Statement of Public Rights of Way” Prepared by the County Council under section 33(1) of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 and section 57(3) of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 The relevant date of this document is 15th December 2007 Published 1st January 2008 Notes: 1. Save as otherwise provided, the prefix SU applies to all grid references 2. The majority of the statements set out in column 5 were prepared between 1950 and 1964 and have not been revised save as provided by column 6 3. Paths numbered with the prefix ‘5’ were added to the definitive map after 1st January 1964 4. Paths numbered with the prefix ‘7’ were originally in an adjoining parish but have been affected by a diversion or parish boundary change since 1st January 1964 5. Paths numbered with the prefix ‘9’ were in an adjoining county on 1st January 1964 6. Columns 3 and 4 do not form part of the Definitive Statement and are included for information only Parish and Path No. Status Start Point (Grid End point (Grid Descriptions, Conditions and Limitations ref and ref and description) description) Footpath 3775 0098 3743 0073 From Road B.3054, southwest of Beaulieu Village, to Parish Boundary The path follows a diverted route between 3810 0150 and East Boldre 703 Beaulieu Footpath Chapel Lane 3829 0170 3 at Parish From B.3054, over stile, southwards along verge of pasture on east side of wire Boundary fence, over stile, south westwards along verge of pasture on southeast side of hedge, over stile, southwards along headland of arable field on east side of hedge, over stile, Beaulieu 3 Footpath 3829 0170 3775 0098 south westwards along verge of pasture on southeast side of hedge, through kissing Hatchet Lane East Boldre gate, over earth culvert, along path through Bulls Wood, through kissing gate, along Footpath 703 at gravel road 9 ft. -

North Hampshire Supported Housing Scheme Leaflet

MENTAL HEALTH NORTH HAMPSHIRE SUPPORTED HOUSING Pentire Montserrat Place 8-bedroom shared house 1-bedroom maisonette Basingstoke Popley Oceana Crescent Beecham Berry Six self-contained fl ats 1-bedroom house Beggarwood Brighton Hill St Nicholas Court Two 1-bedroom houses South Ham PATHWAYS TO Supported Living INDEPENDENCE At Sanctuary Supported Living we deliver personalised care and support services to help people on their pathway to independence. We provide supported housing, move-on accommodation, CQC registered services and floating support. We specialise in services for young people, homeless families and individuals, people with physical disabilities, learning disabilities and people with mental health needs. If you would like this publication in an alternative format please contact us. SUPPORT At North Hampshire Supported Housing, we provide supported housing to adults aged 18 to 65, who have mental health needs. Our structured package of tailored support uses the Mental Health Recovery Star model to agree a personalised support plan, helping residents to identify their needs and aspirations. Their progress is regularly monitored and reviewed, with the plan updated to reflect any changing needs. All support is designed to help residents achieve good emotional health and improve their wellbeing and quality of life. Our highly-trained staff provide a wide range of tailored support, advice and assistance, including: � Daily living skills � Maintaining health, safety and security � Managing finances (budgeting and benefits) � Building confidence, resilience and self-esteem � Maintaining a tenancy � Signposting and accessing other services � Dealing with correspondence � Planning a successful move-on Residents receive low-level support for three hours per week, with the aim of living independently within 18 months to two years. -

So-Resi-Fleet-Brochure2.Pdf

So Resi is a new way of making home ownership possible for more people. You buy a share of your home, with a lower deposit, smaller mortgage and monthly payment on the rest. So Resi redefines shared ownership, by making everything clear and uncomplicated, so you understand how it all works at every stage, before and after you buy. Our So Resi homeowners are important to us and we aim to build strong, lasting relationships by being here to answer your questions in a language that makes sense. So Resi is by Thames Valley Housing, a not-for-profit housing association. We have helped create over 14,500 homes in London and the South-east because we want everyone to have a chance to build their lives from a good home. 3 So Resi Fleet | The development A collection of 1, 2 & 3 bed homes Your perfectly positioned new home 10 miles from Basingstoke and just over 30 miles from London lies So Resi Fleet – a selection of 1, 2 and 3 bedroom homes available through shared ownership. Tucked into the district of Hart, this charming town boasts a host of traditional Victorian features including its quaint high street and is also home to one of the country’s best golf courses. In addition, this leafy location boasts quick access to the M3 linking Fleet to Southampton, the south coast and London to the east. The area 4 Development overview 8 Connectivity 10 Specification 14 Plans 16 4 CGI of homes at So Resi Fleet are for illustrative purposes only and subject to change.