Mesne Process in Personal Actions at Common Law and the Power Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comp9. to UCLA

JURISDICTIONAL COMPETITION AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE COMMON LAW: A H YPOTHESIS * DANIEL KLERMAN Historians explain the development of the common law in many ways. Some emphasize the internal logic of legal concepts,1 while others focus on external factors , such as political, social, or economic conditions.2 A few point to the influence of philosophy3 or other legal systems. 4 For many, the institutional structure of the legal system is the central, whether it be the role of juries,5 the changing dynamics of pleading and post-trial motions, or innovation by lawyers in the service of their clients. 6 Among the institutional factors which influenced legal development, many historians point to competition among courts as an agent of legal change. 7 While references to jurisdictional competition are common in the * Daniel Klerman, Professo r of Law and History, USC Law School, University Park MC-0071, 699 Exposition Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0071, USA [email protected]. Phone: 213 740-7973. Fax: 213 740-5502. The author thanks Lisa Bernstein, Hamilton Bryson, David Crook, Barry Cushman, John de Figueiredo, Richard Epstein, Thomas Gallanis, Joshua Getzler, Gillian Hadfield, Richard Helmholz, Ehud Kamar, Peter Karsten, Timur Kuran, Gregory LaBlanc, Doug Lichtman, James Lindgren, Edward McCaffery, James Oldham, Richard Posner, Jonathan Rose, Eric Talley, Steven Yeazell, Todd Zywicki, and participants in the University of Virginia Law School Faculty Workshop and Australia and New Zealand Legal History Society 2002 annual meeting for comments and suggestions. Unfortunately, many of their ideas and criticisms are not yet reflected in this essay. The author hopes that, as research progresses, their suggestions and concerns will be addressed. -

Summons in a Civil Action UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the ______District of ______

AO 440 (Rev. 06/12) Summons in a Civil Action UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the __________ District of __________ ) ) ) ) Plaintiff(s) ) ) v. Civil Action No. ) ) ) ) ) Defendant(s) ) SUMMONS IN A CIVIL ACTION To: (Defendant’s name and address) A lawsuit has been filed against you. Within 21 days after service of this summons on you (not counting the day you received it) — or 60 days if you are the United States or a United States agency, or an officer or employee of the United States described in Fed. R. Civ. P. 12 (a)(2) or (3) — you must serve on the plaintiff an answer to the attached complaint or a motion under Rule 12 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The answer or motion must be served on the plaintiff or plaintiff’s attorney, whose name and address are: If you fail to respond, judgment by default will be entered against you for the relief demanded in the complaint. You also must file your answer or motion with the court. CLERK OF COURT Date: Signature of Clerk or Deputy Clerk AO 440 (Rev. 06/12) Summons in a Civil Action (Page 2) Civil Action No. PROOF OF SERVICE (This section should not be filed with the court unless required by Fed. R. Civ. P. 4 (l)) This summons for (name of individual and title, if any) was received by me on (date) . ’ I personally served the summons on the individual at (place) on (date) ; or ’ I left the summons at the individual’s residence or usual place of abode with (name) , a person of suitable age and discretion who resides there, on (date) , and mailed a copy to the individual’s last known address; or ’ I served the summons on (name of individual) , who is designated by law to accept service of process on behalf of (name of organization) on (date) ; or ’ I returned the summons unexecuted because ; or ’ Other (specify): . -

Common Law Pleadings in New South Wales

COMMON LAW PLEADINGS IN NEW SOUTH WALES AND HOW THEY GOT HERE John P. Bryson * Advantages and disadvantages para 1 Practice before 1972 para 17 The Texts para 21 Pleadings after the Reform legislation para 26 The system in England before Reform legislation para 63 Recurring difficulties before Reform legislation para 81 The Process of Change in England para 98 How the system reached New South Wales para 103 Procedure in the Court in Banco para 121 Court and Chambers para 124 Diverse Statutes and Procedures para 126 Every-day workings of the system of pleading para 127 Anachronism and Catastrophe para 132 The End para 137 Advantages and disadvantages 1. There can have been few stranger things in the legal history of New South Wales than the continuation until 30 June 1972 of the system of Common Law pleading, discarded in England in 1875 after evolving planlessly over the previous seven Centuries. The Judicature System in England was the culmination of half a century of reform in the procedures and constitution of the courts, prominent among rapid transformations in British economy, politics, industry and society in the Nineteenth Century. With the clamant warning of revolutions in France, the end of the all- engrossing Napoleonic Wars and the enhanced representative character of the House of Commons, the British Parliament and community shook themselves and changed the institutions of society; lest a worse thing happen. As well as reforming itself, the British Parliament in a few decades radically reformed the law relating to the procedure and organisation of the courts, the Established Church, municipal corporations and local government, lower courts, Magistrates and police, 1 corporations and economic organisations, the Army, Public Education, Universities and many other things. -

Legal Fictions As Strategic Instruments

Legal Fictions as Strategic Instruments Daniel Klerman1 USC Law School Preliminary Draft August 14, 2009 Abstract Legal Fictions were one of the most distinctive and reviled features of the common law. Until the mid-nineteenth century, nearly every civil case required the plaintiff to make a multitude of false allegations which judges would not allow the defendant to contest. Why did the common law resort to fictions so often? Prior scholarship attributes legal fictions to a "superstitious disrelish for change" (Maine) or to a deceitful attempt to steal legislative power (Bentham). This paper provides a new explanation. Legal fictions were developed strategically by litigants and judges in order to evade appellate review. Before 1800, judicial compensation came, in part, from fees paid by litigants. Because plaintiffs chose the forum, judges had an incentive to expand their jurisdictions and create new causes of action. Judicial innovations, however, could be thwarted by appellate review. Nevertheless, appellate review was ordinarily restricted to the official legal record, which consisted primarily of the plaintiff's allegations and the jury's findings. Legal fictions effectively insulated innovation from appellate review, because the legal record concealed the change. The plaintiff's allegations were in accord with prior doctrine, and the defendant's attempt to contest fictitious facts was not included in the record. 1 The author thanks Tom Gallanis, Beth Garrett, Dick Helmholz, Mat McCubbins, Roger Noll, Paul Moorman, Pablo Spiller, Matt Spitzer, Emerson Tiller, Barry Weingast, and participants in the USC- Caltech Symposium on Positive Political Theory and the Law for helpful criticism, assistance, and suggestions. -

Fact & Fiction in the Law of Property

University of North Carolina School of Law Carolina Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2007 Fact & Fiction in the Law of Property John V. Orth University of North Carolina School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Publication: Green Bag 2d This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACT & FICTION IN THE LAW OF PROPERTY † John V. O r t h O MODERN AMERICANS “legal fiction” brings to mind the novels of John Grisham or Scott Turow, but to an earlier generation of lawyers the phrase meant a different kind of make-believe. Essentially, legal fiction (in the old Tsense) meant an irrebuttable allegation of a fact without regard to its truth or falsity. The object could be to secure access to a form of procedure that was speedier, cheaper, or simply more likely to pro- duce the desired result. The old action of trover, to recover the value of personal property wrongfully withheld, began with an alle- gation that the property at issue had been lost by the plaintiff and found (trouvé in Law French) by the defendant who converted it to his own use.1 Of course, it was really immaterial how the defendant came to possess the item in question; it could have been purchased, or received as a gift, or actually found. -

Initial Stages of Federal Litigation: Overview

Initial Stages of Federal Litigation: Overview MARCELLUS MCRAE AND ROXANNA IRAN, GIBSON DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP WITH HOLLY B. BIONDO AND ELIZABETH RICHARDSON-ROYER, WITH PRACTICAL LAW LITIGATION A Practice Note explaining the initial steps of a For more information on commencing a lawsuit in federal court, including initial considerations and drafting the case initiating civil lawsuit in US district courts and the major documents, see Practice Notes, Commencing a Federal Lawsuit: procedural and practical considerations counsel Initial Considerations (http://us.practicallaw.com/3-504-0061) and Commencing a Federal Lawsuit: Drafting the Complaint (http:// face during a lawsuit's early stages. Specifically, us.practicallaw.com/5-506-8600); see also Standard Document, this Note explains how to begin a lawsuit, Complaint (Federal) (http://us.practicallaw.com/9-507-9951). respond to a complaint, prepare to defend a The plaintiff must include with the complaint: lawsuit and comply with discovery obligations The $400 filing fee. early in the litigation. Two copies of a corporate disclosure statement, if required (FRCP 7.1). A civil cover sheet, if required by the court's local rules. This Note explains the initial steps of a civil lawsuit in US district For more information on filing procedures in federal court, see courts (the trial courts of the federal court system) and the major Practice Note, Commencing a Federal Lawsuit: Filing and Serving the procedural and practical considerations counsel face during a Complaint (http://us.practicallaw.com/9-506-3484). lawsuit's early stages. It covers the steps from filing a complaint through the initial disclosures litigants must make in connection with SERVICE OF PROCESS discovery. -

Congress's Contempt Power: Law, History, Practice, and Procedure

Congress’s Contempt Power and the Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas: Law, History, Practice, and Procedure Todd Garvey Legislative Attorney May 12, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34097 Congress’s Contempt Power and the Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas Summary Congress’s contempt power is the means by which Congress responds to certain acts that in its view obstruct the legislative process. Contempt may be used either to coerce compliance, to punish the contemnor, and/or to remove the obstruction. Although arguably any action that directly obstructs the effort of Congress to exercise its constitutional powers may constitute a contempt, in recent times the contempt power has most often been employed in response to non- compliance with a duly issued congressional subpoena—whether in the form of a refusal to appear before a committee for purposes of providing testimony, or a refusal to produce requested documents. Congress has three formal methods by which it can combat non-compliance with a duly issued subpoena. Each of these methods invokes the authority of a separate branch of government. First, the long dormant inherent contempt power permits Congress to rely on its own constitutional authority to detain and imprison a contemnor until the individual complies with congressional demands. Second, the criminal contempt statute permits Congress to certify a contempt citation to the executive branch for the criminal prosecution of the contemnor. Finally, Congress may rely on the judicial branch to enforce a congressional subpoena. Under this procedure, Congress may seek a civil judgment from a federal court declaring that the individual in question is legally obligated to comply with the congressional subpoena. -

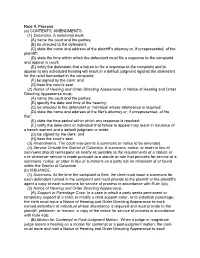

Rule 4. Process (A) CONTENTS; AMENDMENTS. (1) Summons. a Summons Must: (A) Name the Court and the Parties; (B) Be Directed to Th

Rule 4. Process (a) CONTENTS; AMENDMENTS. (1) Summons. A summons must: (A) name the court and the parties; (B) be directed to the defendant; (C) state the name and address of the plaintiff’s attorney or, if unrepresented, of the plaintiff; (D) state the time within which the defendant must file a response to the complaint and appear in court; (E) notify the defendant that a failure to file a response to the complaint and to appear at any scheduled hearing will result in a default judgment against the defendant for the relief demanded in the complaint; (F) be signed by the clerk; and (G) bear the court’s seal. (2) Notice of Hearing and Order Directing Appearance. A Notice of Hearing and Order Directing Appearance must: (A) name the court and the parties; (B) specify the date and time of the hearing; (C) be directed to the defendant or individual whose attendance is required; (D) state the name and address of the filer’s attorney or, if unrepresented, of the filer; (E) state the time period within which any response is required; (F) notify the defendant or individual that failure to appear may result in issuance of a bench warrant and a default judgment or order; (G) be signed by the clerk; and (H) bear the court’s seal. (3) Amendments. The court may permit a summons or notice to be amended. (4) Service Outside the District of Columbia. A summons, notice, or order in lieu of summons should correspond as nearly as possible to the requirements of a statute or rule whenever service is made pursuant to a statute or rule that provides for service of a summons, notice, or order in lieu of summons on a party not an inhabitant of or found within the District of Columbia. -

Personal Jurisdiction in Illinois, Jenner & Block Practice Series 2020

J E N N E R & B L O C K Practice Series Personal Jurisdiction in Illinois Paul B. Rietema Skyler J. Silvertrust Maria C. Liu JENNER & BLOCK LLP OFFICES • 353 North Clark Street • 633 West Fifth Street, Suite 3500 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3456 Los Angeles, California 90071-2054 Firm: 312 222-9350 Firm: 213 239-5100 Fax: 312 527-0484 Fax: 213 239-5199 • 919 Third Avenue • 1099 New York Avenue, N.W., Suite 900 New York, New York 10022-3908 Washington, D.C. 20001-4412 Firm: 212 891-1600 Firm: 202 639-6000 Fax: 212 891-1699 Fax: 202 639-6066 • 25 Old Broad Street London EC2N 1HQ, United Kington Firm: 44 (0) 333 060-5400 Fax: 44 (0) 330 060-5499 Website: www.jenner.com AUTHOR INFORMATION1 • PAUL B. RIETEMA • SKYLER J. SILVERTRUST Partner Associate Tel: 312 840-7208 Tel: 312 840-7214 Fax: 312 840-7308 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] • MARIA C. LIU Associate Tel: 202 637-6371 E-Mail: [email protected] 1 The authors would like to thank Michael A. Doornweerd and A. Samad Pardesi for their substantial contributions to prior versions of this Practice Guide. © 2020 Jenner & Block LLP. Attorney Advertising. Jenner & Block is an Illinois Limited Liability Partnership including professional corporations. This publication is not intended to provide legal advice but to provide information on legal matters and firm news of interest to our clients and colleagues. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to matters mentioned in this publication. The attorney responsible for this publication is Brent E. -

Early Bills in Equity

EARLY BILLS IN EQUITY. "The first attempt to clear up the story of the Bill as we find it in the -early Year Books, resulted in the conviction that the Bill as it was known in those early times had been respectfully neglected by all our writers upon the early law." These words, written some years agb, were the result of a prolonged search through all the authorities for some reference to the early pro- cedure by bill instead of by writ: It was then found that the story of the Bill, as we begin how to be able to tell it, was not told in any of the histories of the law, or in any of the treatises upon equity. These bills were dimly suggested in the cases found in the early Year Books, but they were only suggested,, and any inquiry only led to the answer that the bill in question must be the Bill of .Middlesex. But it was clear that the Bills in ques- tion had nothing to do with the custody of the Marshall; they plainly bore no relation to the Bill of Middlesex. Crabb alone among historians seemed to have some faint idea of this other bill, for he says, "There were other modes of proceeding, of more anciefit date than that by writ, which were more adapted to the extraordinary jurisdiction exercised by our kings at an early period, in the administration of justice. One of these proceedings was by bill." 1 Reeves, in his "History of English," shows that he knows something about bills, but has no authority to give for his knowledge, and he refuses to answer the questions about them which had evidently been put before him. -

Child Support Bench Book: Indirect Civil Contempt for Failure to Pay Child Support TABLE of CONTENTS

Child Support Bench Book: Indirect Civil Contempt for Failure to Pay Child Support TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 A. Legal Authority................................................................................................................... 1 II. Overview of Contempt Action .................................................................................................. 2 A. Prima Facie Case & Burden of Proof................................................................................. 2 B. Purpose................................................................................................................................ 2 C. Sentencing ........................................................................................................................... 3 D. Court Liaison Program........................................................................................................ 3 E. Is Contempt a Good Remedy?............................................................................................. 3 III. Screening Process .................................................................................................................... 4 A. Review and Research.......................................................................................................... 4 B. Assessing Case against Obligor ......................................................................................... -

Circuit Court Clerks' Manual

CIRCUIT COURT CLERKS’ MANUAL - CIVIL GLOSSARY PAGE 1 A ADDENDUM Something to be added, especially to a document; a supplement. ADJUDICATE To decide judicially. The acknowledgement or recognition in a pleading by one party of the truth of some matter alleged by the opposite party through a ADMISSIONS Request for Admissions, the effect of which is to narrow the area of facts or allegations required to be proved by evidence. A written, printed, or videotaped declaration or statement of facts, made voluntarily, and confirmed by the oath or affirmation of the AFFIDAVIT party making it, taken before an officer having authority to administer such oath. A judicial proceeding in which a party seeks to confirm or ratify AFFIRMATION OF that a valid marriage exists between that party and the other party MARRIAGE to the suit. One growing out of or auxiliary to another action or suit, or which ANCILLARY is subordinate to or in aid of a primary action, either law or in PROCEEDING chancery. Any process which is in aid of or incidental to the principal suit or ANCILLARY PROCESS action; e.g. attachment. A judicial proceeding in which one party seeks to nullify a void or ANNULMENT voidable marriage. A voidable marriage is valid until annulled, while a void marriage never was a valid marriage. A pleading by which defendant in civil suit at law endeavors to resist the plaintiff's demand by stating facts. The defendant may ANSWER deny the claims of the plaintiff, or agree to them, and may introduce new matter. The party who appeals a case from a court to another court having APPELLANT appellant jurisdiction over the case being appealed.