Call a 3D Locksmith – How 3D Printing Can Defeat Physical Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCKSMITH Dictionary

LOCKSMITH Dictionary Copyright , 1982 by the ALOA Sponsored National Task Group for Certified Training Programs, Master Keying Study Group Copyright , 1983 by the ALOA Sponsored National Task Group for Certified Training Programs, Master Keying Study Group Revised June, 1984 Copyright , 1996 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council, Master Keying Study Group Copyright , 1997 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2000 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2001 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2002 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2003 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2004 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2005 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2006 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2007 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2009 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2010 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2011 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2012 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Study group and LIST Council members have included: Jerome Andrews Vaughan Armstrong Jimmy Benvenutti Greg Brandt Breck H. Camp Joe Cortie Billy B. Edwards Jr. Ken Ehrenreich G.L. Finch Dorothy Friend Kristine Gallo Ray Hern A.J. Hoffman Wiegand Jensen David J. Killip Mike Kirkpatrick William Lynk Gordon S. Morris Dan Nicholson Don O'Shall Brian O'Dowd Lloyd Seliber Jon Payne Sharon Smith John Truempy Roger Weitzenkamp Jym Welch All rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted to reprint terms and definitions contained herein with the following stipulations: 1. -

7000-0581: Government Products Price List

Effective November 15, 2019 z Government Products Price List Security Products Made To Meet Exacting U.S. Government Standards MAKE-TO-ORDER CAPABILITY SECURITY PRODUCTS BUILT AND KEYED TO YOUR REQUIREMENTS 1 SHACKLE OPTIONS Choose extra length shackles 2 KEYING FLEXIBILITY Over 60 padlock, door hardware and interchangeable core keyways available Choose keying – KD, KA, MK, GMK 3 CHOOSE CUSTOM LASER ENGRAVING ON SOLID BRASS LOCKS EDGE® KEY CONTROL ADVANCED CYLINDER Prevents unauthorized TECHNOLOGY duplication of keys Excellent protection against lock bumping To learn more about Government Table of Contents security products and accessories, Terms of Sale 3 contact your dealer or visit Ordering Information 3 americanlock.com and BumpStop® 4 masterlock.com Government Products 5 American Lock - Build Your Lock 6 - New NSN Listing 8 - Existing NSN Listing 9 24/7 On-Line Ordering Master Lock & Quoting Resource* - Build Your Lock 10 MasterLockShop.com - NSN Listing 11 Accurately enter orders, - Resettable Combination Locks 13 validate key numbers and - Key Cabinets 14 create laser engraved orders. Service Parts 14 * A Master Lock account number is required to use this system. No minimum order size. TERMS OF SALE THE MASTER LOCK COMPANY TERMS OF SALE – EFFECTIVE NOVEMBER 2019 All orders are subject to acceptance by Master Lock Company LLC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA PRICES: ■ Concealed damages must be reported within five business days of ■ All prices are stated in US dollars ($). receipt of merchandise in order to determine liability. ■ Orders are subject to prevailing prices on order acceptance date. ■ All carriers’ claims on Prepaid (or Prepay & Add) shipments are filed by ■ 10% will be added for less than Master Carton quantities per customer Master Lock Company LLC. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Ordering Information .....................................A1 General Information .......................................A3 New Products ..........................................B5 Kwikset Signature Series ........................C19 Handlesets ....................................................C20 Levers ............................................................C21-22 Knobs ............................................................C23-24 Combo Packs ................................................C25 Deadbolts ......................................................C26 Kwikset ...................................................D27 Handlesets ....................................................D28 Levers ...........................................................D29 Knobs ............................................................D30-31 Combo Packs ................................................D32 Project Packs ................................................D33 Deadbolts ......................................................D34 Electronic Locks ......................................E35 Deadbolts ......................................................E35 Levers ...........................................................E35 Light Commerical ....................................F37 Key Control Deadbolt ...................................F37 Parts & Accessories ................................ Latches ..........................................................G39 Rekeying Kit & Parts ......................................G40 -

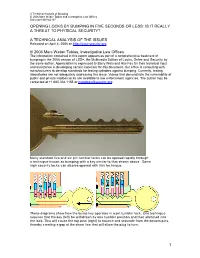

1 Opening Locks by Bumping in Five Seconds Or Less: Is It Really a Threat to Physical Security? a Technical Analysis of The

A Technical Analysis of Bumping © 2006 Marc Weber Tobias and Investigative Law Offices Document 060922107 OPENING LOCKS BY BUMPING IN FIVE SECONDS OR LESS: IS IT REALLY A THREAT TO PHYSICAL SECURITY? A TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ISSUES Released on April 4, 2006 on http://www.security.org © 2006 Marc Weber Tobias, Investigative Law Offices The information contained in this report appears as part of a comprehensive treatment of bumping in the 2006 version of LSS+, the Multimedia Edition of Locks, Safes and Security by the same author. Appreciation is expressed to Barry Wels and Han Fey for their technical input and assistance in developing certain materials for this document. Our office is consulting with manufacturers to develop standards for testing cylinders against bumping. Currently, testing laboratories are not adequately addressing this issue. Videos that demonstrate the vulnerability of public and private mailbox locks are available to law enforcement agencies. The author may be contacted at +1.605.334.1155 or [email protected]. Many standard five and six pin tumbler locks can be opened rapidly through a technique known as bumping with a key similar to that shown above. Some high security locks can also be opened with this technique. These diagrams show how the bump key operates in a pin tumbler lock. One technique requires that the key (left) be withdrawn by one tumbler position and then slammed into the lock. This will cause the top pins (right) to bounce and separate from the bottom pins, thereby creating a gap at the shear line that will allow the plug to turn. -

Visit Us Online! Catalog No

PRODUCTS VISIT US ONLINE! CATALOG WWW.MOVENSTORE.COM NO. 41 About Move ‘N Store MOVE ’N STORE is one of the oldest and largest national suppliers of moving and storage, packaging and security products to the world-wide self-storage and self-move industries. Whether you operate one facility, a handful or hundreds, Move ’N Store’s unparalleled products, service and delivery can help you increase retail sales and profits, streamline the ordering process and insure your customers’ satisfaction. MOVE ’N STORE PRODUCTS Move ’N Store offers a full line of self-storage/self move retail products including: • Padlocks • Mattress and furniture covers • Moving and storage boxes (in selected markets) • Moving tools and accessories • Packing materials All Move ’N Store moving and storage products, including boxes and packaging materials, carry our Professional Movers Grade seal, your guarantee of quality and product reliability. These products are certified by Move ’N Store to meet or exceed the rigorous quality and performance standards demanded by moving industry professionals. In addition to retail products, Move ’N Store also offers facility maintenance products such as keyed-alike padlocks, lock removal tools, shelving and replacement door hardware, as well as exclusive products including the MiniWrite manual bookkeeping system, Everbrite™ protective door coatings and Ideal Shield bumper post sleeves. SERVICE COMMITMENT All Move ’N Store Customer Account Representatives, distribution specialist and customer service personnel, are experienced industry professionals who are committed to your complete satisfaction. And we guarantee it. If there’s ever a problem with an order, a delivery or a Move ’N Store product, we’ll make it right...right away. -

7000-0575: Commercial Price List November 2018

Effective November 1, 2018 Electronic Update November 2018 2018 Commercial Security Price List Master Lock offers the widest range of high quality, customizable, security products available. Businesses and facilities have security needs that require strong, durable products with the ability to adapt to unique applications as well as multiple users. Master Lock continues to expand its commercial products and services to provide customers security solutions for all security points. And, all products are backed by our dedicated Customer Service and Sales teams. MAKE-TO-ORDER CAPABILITY SECURITY PRODUCTS BUILT AND KEYED TO YOUR REQUIREMENTS 1 SHACKLE OPTIONS Choose different shackle materials and extra length shackles 2 KEYING FLEXIBILITY Dept. 502 Over 60 padlock, door hardware and interchangeable core keyways available Choose keying – KD, KA, MK, GMK 3 CHOOSE CUSTOM MARKING Laser engraving, hard stamping and pad printing EDGE® KEY CONTROL ADVANCED CYLINDER SERVICE PARTS Prevents unauthorized TECHNOLOGY Support for dealers duplication of keys Excellent protection against lock bumping 24/7 On-Line Customer Service Online Resources Ordering & & Sales Support MasterLock.com * Quoting Resource 1-800-308-9242 MasterLockShop.com MasterLockShop.com Over 75 dedicated and Masterease.com Accurately enter orders, knowledgeable employees BuildYourLock.com validate key numbers ready to serve you. MasterLockImages.com and create laser engraved orders. * A Master Lock account number is required to use this system. No minimum order size. TERMS OF SALE THE MASTER LOCK COMPANY TERMS OF SALE – EFFECTIVE NOVEMBER 2018 All orders are subject to acceptance by Master Lock Company LLC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA PRICES: ■ Concealed damages must be reported within five business days of ■ All prices are stated in US dollars ($). -

Listen to Your Key: Towards Acoustics-Based Physical Key Inference

Listen to Your Key: Towards Acoustics-based Physical Key Inference Soundarya Ramesh Harini Ramprasad Jun Han [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science National University of Singapore National University of Singapore National University of Singapore ABSTRACT Physical locks are one of the most prevalent mechanisms for secur- ing objects such as doors. While many of these locks are vulnerable to lock-picking, they are still widely used as lock-picking requires specific training with tailored instruments, and easily raises suspi- cion. In this paper, we propose SpiKey, a novel attack that signifi- cantly lowers the bar for an attacker as opposed to the lock-picking attack, by requiring only the use of a smartphone microphone to in- fer the shape of victim’s key, namely bittings (or cut depths) which form the secret of a key. When a victim inserts his/her key into the lock, the emitted sound is captured by the attacker’s microphone. SpiKey leverages the time difference between audible clicks to ulti- mately infer the bitting information, i.e., shape of the physical key. As a proof-of-concept, we provide a simulation, based on real-world recordings, and demonstrate a significant reduction in search space from a pool of more than 330 thousand keys to three candidate keys for the most frequent case. CCS CONCEPTS · Security and privacy → Side-channel analysis and counter- measures;· Hardware → Sound-based input / output. KEYWORDS Figure 1: Figure depicts SpiKey attack scenario. -

Key Control and Data Security: Protecting Your Customer's Files

Key Control and Data Security : Protecting Your Customer’s Files Keep each customer’s files secure with the Lock America Key Control Program. Rich Morahan © March 2011, Rich Morahan Consider this scenario: 2 Lawyers 1 Shredding Company 1 Key code Is this a Secure Information Destruction System? Key Control Systems Data Destruction Security Rich Morahan Slide 2 Is one key code the secure way to protect your customers’ sensitive files waiting for shredding? Marshall & McLuhan, Esq., Law Offices Ginsburg & Burroughs, Esq., Law Offices Are you using the same key code for all your clients? Key Control Systems Data Destruction Security Rich Morahan Slide 3 If every one of your customers has the same key code, no customer’s files are secure Standard Low Security key— code 123 Customer A— Customer B— Customer C— Code 123 Code 123 code 123 Should every one of your customers have access to every other customer’s data? That’s the situation if you use the same key code and a low security lock and key for all your customers. A competitor, a criminal or a disgruntled employee can easily duplicate a standard key, or pick or “bump” a low security lock. And no one will know what they did until the damage is done . Your customer’s files are secure ONLY if each customer has his own unique key code. Key Control Systems Data Destruction Security Rich Morahan Slide 4 You have two options to protect your customers’ files: Standard Security or Registered Security THE STANDARD SECURITY OPTION: Supply each customer with a different standard security key. -

Commercial Security Price List

Commercial Security Price List Effective July 1, 2015 Master Lock offers the widest range of high quality, customizable, security products available. Businesses and facilities have security needs that require strong, durable products with the ability to adapt to unique applications as well as multiple users. Master Lock continues to expand its commercial products and services to provide customers security solutions for all security points. And, all products are backed by our dedicated Customer Service and Sales teams. MAKE-TO-ORDER CAPABILITY SECURITY PRODUCTS BUILT AND KEYED TO YOUR REQUIREMENTS 1 SHACKLE OPTIONS Choose different shackle materials and extra length shackles 2 KEYING FLEXIBILITY Dept. 502 Over 60 padlock, door hardware and interchangeable core keyways available Choose keying – KD, KA, MK, GMK 3 CHOOSE CUSTOM MARKING Laser engraving, hard stamping and pad printing EDGE® KEY CONTROL ADVANCED CYLINDER MERCHANDISING DISPLAYS Prevents unauthorized TECHNOLOGY & SERVICE PARTS duplication of keys Exceeds ASTM F883-09 Grade Support for dealers 6 for lock bumping resistance 24/7 On-Line Customer Service Online Resources Ordering & & Sales Support MasterLock.com * Quoting Resource 1-800-308-9242 MasterLockShop.com MasterLockShop.com Over 75 dedicated and Masterease.com Accurately enter orders, knowledgeable employees BuildYourLock.com validate key numbers ready to serve you. MasterLockImages.com and create laser engraved orders. * A Master Lock account number is required to use this system. No minimum order size. TERMS OF SALE MASTER LOCK COMPANY TERMS OF SALE – EFFECTIVE JULY 2015 All orders are subject to acceptance by Master Lock Company LLC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA PRICES: RETURNED GOODS: ■ All prices are stated in US dollars ($). -

Master Lock Commercial Security Products Technical Manual

Commercial Security Products TECHNICAL MANUAL ISSUE 06.13 Electronic Update September 2013 Table of Contents Index by Model No. 1 ProSeries ® 6270 & 6271 Lock Service Procedure 2 ProSeries ® Rekeyables Service Procedure 3 ProSeries ® 6230 Locks Service Procedure 5 ProSeries ® Rekeyables Component Parts 4,6 ProSeries ® Interchangeable Core Service Procedure 7 ProSeries ® Interchangeable Core Component Parts 8 ProSeries ® Door Hardware Service Procedure 9 ProSeries ® Door Hardware Component Parts 10 21, 24, 25, 27 and 101 Laminated Rekeyables Service Procedure 11 Python ™ Cylinder Compatible Products Service Procedure 11 Cylinders and Retainers 13-17 Cylinder Service Procedure 18 Keying 19-22 Improved 6000 and 7000 Keyways 23 Keys and Keyways 24 Bitting Specifications 25 ProSeries ® Actuators, Retainers and Drivers 26-27 Tools 28 Lock Lubricants 29 Terminology 30-38 Model Number Index Service Procedures and Parts Service Service Service Service Product No. Procedure Parts Product No. Procedure Parts Product No. Procedure Parts Product No. Procedure Parts 6121 346427 786836 787036 78 6125 346521 786840 347040 36 6127 346527 786841 787041 78 6230 566621 9 10 6842 9 10 7042 9 10 6270 226627 9 10 6850 367045 36 6271 226721 9 10 6851 787046 78 6321 346727 9 10 6852 9 10 7047 9 10 6325 346830 347030 367050 36 6327 346831 787031 787051 78 6421 786835 367035 367052 9 10 1 Master Lock introduced the ProSeries ® product line in 1992 with Weather Tough ® and High Security, iron shrouded, rekeyable padlocks. Intent on providing locksmiths with greater ease and flexibility, Master Lock designed the padlocks to use standard components across the line. Since then, ProSeries ® has grown to include solid body padlocks in Brass, Steel and Aluminum to further satisfy corrosion, security and safety requirements. -

Cylinder Lock and Latch Systems

Key Control and Data Security: Protecting Your Customer’s Files Keep each customer’s files secure with the Lock America Key Control Program. Rich Morahan © March 2011, Rich Morahan Consider this scenario: 2 Lawyers 1 Shredding Company 1 Key code Is this a Secure Information Destruction System? Key Control Systems Data Destruction Security Rich Morahan Slide 2 Is one key code the secure way to protect your customers’ sensitive files waiting for shredding? Marshall & McLuhan, Esq., Law Offices Ginsburg & Burroughs, Esq., Law Offices Are you using the same key code for all your clients? Key Control Systems Data Destruction Security Rich Morahan Slide 3 If every one of your customers has the same key code, no customer’s files are secure… Standard Low Security key— code 123 Customer A— Customer B— Customer C— Code 123 Code 123 code 123 Should every one of your customers have access to every other customer’s data? That’s the situation if you use the same key code and a low security lock and key for all your customers. A competitor, a criminal or a disgruntled employee can easily duplicate a standard key, or pick or “bump” a low security lock. And no one will know what they did until the damage is done. Your customer’s files are secure ONLY if each customer has his own unique key code. Key Control Systems Data Destruction Security Rich Morahan Slide 4 You have two options to protect your customers’ files: Standard Security or Registered Security THE STANDARD SECURITY OPTION: Supply each customer with a different standard security key. -

Master Lock Technical Manual

Commercial Security Products TECHNICAL MANUAL ISSUE 06.13 Electronic Update September 2013 Table of Contents Index by Model No. 1 ProSeries ® 6270 & 6271 Lock Service Procedure 2 ProSeries ® Rekeyables Service Procedure 3 ProSeries ® 6230 Locks Service Procedure 5 ProSeries ® Rekeyables Component Parts 4,6 ProSeries ® Interchangeable Core Service Procedure 7 ProSeries ® Interchangeable Core Component Parts 8 ProSeries ® Door Hardware Service Procedure 9 ProSeries ® Door Hardware Component Parts 10 21, 24, 25, 27 and 101 Laminated Rekeyables Service Procedure 11 Python ™ Cylinder Compatible Products Service Procedure 11 Cylinders and Retainers 13-17 Cylinder Service Procedure 18 Keying 19-22 Improved 6000 and 7000 Keyways 23 Keys and Keyways 24 Bitting Specifications 25 ProSeries ® Actuators, Retainers and Drivers 26-27 Tools 28 Lock Lubricants 29 Terminology 30-38 Model Number Index Service Procedures and Parts Service Service Service Service Product No. Procedure Parts Product No. Procedure Parts Product No. Procedure Parts Product No. Procedure Parts 6121 346427 786836 787036 78 6125 346521 786840 347040 36 6127 346527 786841 787041 78 6230 566621 9 10 6842 9 10 7042 9 10 6270 226627 9 10 6850 367045 36 6271 226721 9 10 6851 787046 78 6321 346727 9 10 6852 9 10 7047 9 10 6325 346830 347030 367050 36 6327 346831 787031 787051 78 6421 786835 367035 367052 9 10 1 Master Lock introduced the ProSeries ® product line in 1992 with Weather Tough ® and High Security, iron shrouded, rekeyable padlocks. Intent on providing locksmiths with greater ease and flexibility, Master Lock designed the padlocks to use standard components across the line. Since then, ProSeries ® has grown to include solid body padlocks in Brass, Steel and Aluminum to further satisfy corrosion, security and safety requirements.