Foreign Assistance: an Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance in Recipient Countries?

Working Paper in Economics # 201811 December 2018 Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance in Recipient Countries? Ranjula Bali Swain and Supriya Garikipati https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/management/people/economics/ © Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance in Recipient Countries? Ranjula Bali Swain and Supriya Garikipati* Abstract An explicit goal of foreign aid is to promote female empowerment and gender equality in developing countries. The impact of foreign aid on these latent variables at the country level is not yet known because of various methodological impediments. We address these by using Structural Equation Models. We use data from the World Development Indicators, the World Governance Indicators and the OECDs Credit Reporting System to investigate if foreign aid has an impact on gender performance of recipient countries at the country level. Our results suggest that to observe improvement in gender performance at the macro-level, foreign aid must target the gender outcomes of interest in a clearly measurable ways. JEL classifications: O11, J16, C13 Keywords: foreign aid, gender performance, structural equation model. 1. Introduction Gender entered the development dialogue over the period 1975-85 which came to be marked by the United Nations as the UN Decade for Women. The accumulating evidence over this period suggests that economic and social developments are not gender-neutral and improving gender outcomes has important implications both at the household and country levels, especially for the prospect of intergenerational wellbeing (Floro, 1995; Klasen, 1999). Consequentially, gender equality came to be widely accepted as a goal of development, as evidenced particularly by its prominence in the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) and, later on, in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). -

THE HISTORY of INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AID David

1 THE HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AID David Williams Introduction The provision of aid to developing countries has become an increasingly important part of contemporary international relations. The number of aid donors has increased, and the total amount of aid given to developing countries has risen significantly, especially in the last 10 years or so. For many developing countries, relations with development agencies have become a central part of their international affairs, and for some of the most aid dependent states, foreign assistance has become central to their ability to provide services to their population. For western states, the provision of development aid has become an important instrument for achieving international objectives including the cultivating of political allies, opening markets, fighting terrorism, and constructing regimes of global governance. The provision of foreign aid has also been very controversial. There is an important (and very lively!) debate about how effective foreign aid has been in stimulating development, and thus about whether donor countries ought to be more generous in their aid provision. In addition, over the last ten years or so, there has been increasing pressure on western donors to provide aid in a more effective, coordinated and transparent manner. For all of these reasons, foreign aid is in important site of investigation into changing practices of global economic governance. Given the centrality of foreign aid to contemporary international politics, it is easy to forget that as an institutionalized activity it is a relatively recent phenomenon. While there are important precedents, the provision of foreign aid results largely from the newly dominant position of the United States at the end of World War Two. -

Does Offshoring Asylum and Migration Actually Work? What Australia, Spain, Tunisia and the United States Can Teach the Eu

POLICY BRIEF | September 2018 DOES OFFSHORING ASYLUM AND MIGRATION ACTUALLY WORK? WHAT AUSTRALIA, SPAIN, TUNISIA AND THE UNITED STATES CAN TEACH THE EU Giulia Laganà Senior Analyst, EU migration and asylum Open Society European Policy Institute POLICY BRIEF | September 2018 INTRODUCTION: IS OFFSHORING HERE TO STAY AND HOW IS ITS SUCCESS MEASURED? As the stalemate continues over a common set Refugee Convention and its Protocols. Others have of rules on asylum within the European Union, highlighted the fact that the route is not actually ‘externalising’, ‘offshoring’, ‘outsourcing’ and, closed as thousands continue to move through the most recently, ‘regionalising’ asylum and migration Western Balkans, where they are met by increasingly management in non-EU countries appear to be the harsh border enforcement, in a desperate bid to buzzwords of the moment. But is the idea of involving reach the EU. Despite this, the agreement with Turkey countries outside the bloc to stem arrivals really is still touted as a success, as measured by the new? As early as the mid-1990s, when Denmark and primary yardstick - arrivals are down dramatically the Netherlands proposed hosting asylum seekers compared to the peak period in 2015-2016. outside Europe, various forms of this concept have surfaced periodically in the European debate – only The third reason why the periodic recurrence of to be regularly discarded for a host of both legal and calls to offshore or externalise migration may be practical reasons. entering a new phase is that the crisis mentality has stuck despite a significant fall in the number The sustained arrivals in 2015-2016, however, of irregular migrants reaching the EU over the last changed this dynamic in a number of ways. -

An Example of Development Aid

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Reuter, H.-Jochen Article — Digitized Version An example of development aid Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Reuter, H.-Jochen (1967) : An example of development aid, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Verlag Weltarchiv, Hamburg, Vol. 02, Iss. 6/7, pp. 171-173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02929850 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/137763 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu mic and social problems of Latin America. This is also development. However, it must gradually come to be the slant of the resolutions dealing with restricting realised that any type of economic integration is, in military expenditure; these are aimed at concentrat- the final analysis, a political act. -

424 Public Law 87-194 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House Of

424 PUBLIC LAW 87-194-SEPT. 1, 1961 [75 ST AT. Public Law 87-194 September 1, 1961 AN ACT [H. R. 7809] To improve the active duty promotion opportunity of Air Force ofllcers from the grade of major to the grade of lieutenant colonel. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of tJie Air Force offl- United States of America in Congress assembled^ That, during the period beginning on the date of enactment of this Act and ending at the close of June 30, 1963, any authorized strength prescribed for the grade of lieutenant colonel by or under section 8202 of title 10, 70A Stat. 498. United States Code, may be exceeded by not more than four thousand. Approved September 1, 1961. Public Law 87-195 September 4. 1961 AN ACT [S.1983] To promote the foreign policy, security, and general welfare of the United States by assisting peoples of the world in their efforts toward economic development and internal and external security, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the The Foreign As- United States of America in Congress assembled^ sistance Act of 1961. Post, p. 719. PART I CHAPTER 1—SHORT TITLE AND POLICY Act for Interna tional Develop- SEC. 101. SHORT TITLE.—This part may be cited as the "Act for ment of 1961. International Development of 1961". SEC. 102. STATEMENT OF POLICY.—It is the sense of the Congress that peace depends on wider recognition of the dignity and interde pendence of men, and survival of me institutions in the United States can best be assured in a worldwide atmosphere of freedom. -

The IMF and Gender Equality: a Compendium of Feminist Macroeconomic Critiques OCTOBER 2017

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Compendium of Feminist Macroeconomic Critiques OCTOBER 2017 The gender dimensions of the IMF’s key fiscal policy advice on resource mobilisation in developing countries The IMF and Gender Equality Abbreviations APMDD Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development ARB Asociación de Recicladores de Bogotá BWP Bretton Woods Project CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women CESR Center for Economic and Social Rights FAD Fiscal Affairs Department GEM Gender Equality and Macroeconomics ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights IEO International Evaluation Office IFIs International Financial Institutions ILO International Labor Organization IMF International Monetary Fund INESC Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos ITUC International Trade Union Confederation LIC Low Income Country MDGs Millennium Development Goals SMSEs small and medium sized enterprises ODA Overseas Development Aid OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development PWDs Persons with Disabilities SDGs Sustainable Development Goals TA Technical Assistance UN United Nations UNDP United Nations Development Programme VAT Value Added Tax VAWG Violence against Women and Girls WHO World Health Organization WIEGO Women in Informal Employment, Globalizing and Organizing WILPF Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Publisher: Bretton Woods Project October 2017 Copyright notice: This text may be freely used providing the source is credited 2 The IMF and Gender Equality Table of Contents Abbreviations 2 Executive summary 5 Acknowledgements 6 I. Positioning women’s rights and gender equality in the macroeconomic policy environment Emma Bürgisser and Sargon Nissan Bretton Woods Project 9 II. The gender dimensions of the IMF’s key fiscal policy advice on resource mobilisation in developing countries Mae Buenaventura and Claire Miranda Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development 16 III. -

Making Development Aid More Effective the 2010 Brookings Blum Roundtable Policy Briefs Ccontentsontents

SEPTEMBER 2010 Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS MAKING DEVELOPMENT AID MORE EFFECTIVE THE 2010 BROOKINGS BLUM ROUNDTABLE POLICY BRIEFS CCONTENTSONTENTS Can Aid Catalyze Development? ...................................................................................................................3 Homi Kharas Brookings U.S. Government Support for Development Outcomes: Toward Systemic Reform ........................................10 Noam Unger Brookings The Private Sector and Aid Effectiveness: Toward New Models of Engagement .............................................20 Jane Nelson Harvard University and Brookings International NGOs and Foundations: Essential Partners in Creating an Effective Architecture for Aid ..........28 Samuel A. Worthington, InterAction and Tony Pipa, Independent consultant Responding to a Changing Climate: Challenges in Financing Climate-Resilient Development Assistance ....37 Kemal Derviş and Sarah Puritz Milsom Brookings Civilian-Military Cooperation in Achieving Aid Effectiveness: Lessons from Recent Stabilization Contexts ...48 Margaret L. Taylor Council on Foreign Relations Rethinking the Roles of Multilaterals in the Global Aid Architecture ............................................................55 Homi Kharas Brookings INTRODUCTION The upcoming United Nations High-Level Plenary From high-profile stabilization contexts like Meeting on the Millennium Development Goals will Afghanistan to global public health campaigns, and spotlight global efforts to reduce poverty, celebrat- from a renewed -

Toward a Feminist Funding Ecosystem

Toward a Feminist Funding Ecosystem 01 | Toward a Feminist Funding Ecosystem | October 2019 CREDits The Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) is a global, feminist, membership, movement-support organization. We support feminist, women’s rights and gender justice movements to thrive, to be a driving force in challenging systems of oppression, and to co-create feminist realities. www.awid.org Toward A Feminist Funding Ecosystem October 2019 Authors: Kellea Miller and Rochelle Jones Contributors: Tenzin Dolker, Kasia Staszewska, Hakima Abbas, Inna Michaeli, and Laila Malik Designer: Chelsea Very AWID gratefully acknowledges the many people whose ideas and inspiration have shaped this report: Angelika Arutyunova, whose vision is at the heart of this project; Åsa Elden, who worked with the Resourcing Feminist Movements Team to develop AWID’s initial ecosystem framework; Michael Edwards, whose thought leadership has pushed the edges of philanthropy for many years; our partners within the Count Me In! Consortium (CMI!) and all the participants of the 2018 CMI! Money & Movements Convening, where many of these ideas were explored and refined; and many current and former AWID staff members, including especially Alejandra Sardá- Chandiramani, Cindy Clark, Fenya Fischler, Nerea Craviotto, and Kamardip Singh. We would also like to thank our donors and members for their generous support. Finally and most importantly, we acknowledge the bold movements that are building more just, feminist realities around the world. We hope this report can contribute to better and more sustained resourcing of your vital and vibrant organizing. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) www.creativecommons.org This publication may be redistributed non-commercially in any media, unchanged and in whole, with credit given to AWID and the authors. -

Tied Aid, Trade-Facilitating Aid Or Trade-Diverting Aid?

Working Paper 2009:5 Department of Economics Tied Aid, Trade-Facilitating Aid or Trade-Diverting Aid? Lars M. Johansson and Jan Pettersson Department of Economics Working paper 2009:4 Uppsala University March 2009 P.O. Box 513 ISSN 1653-6975 SE-751 20 Uppsala Sweden Fax: +46 18 471 14 78 TIED AID, TRADE-FACILITATING AID OR TRADE-DIVERTING AID? LARS M. JOHANSSON AND JAN PETTERSSON Papers in the Working Paper Series are published on internet in PDF formats. Download from http://www.nek.uu.se or from S-WoPEC http://swopec.hhs.se/uunewp/ Tied Aid, Trade-Facilitating Aid or Trade-Diverting Aid?∗ Lars M. Johanssonyand Jan Petterssonz March 9, 2009 Abstract Donor aid is often regarded as being informally tied (aid increases donor- recipient exports) and this effect is, in general, interpreted as being harmful to aid recipients. However, in this paper, using a gravity model, we show that aid is also positively associated with recipient-donor exports. That is, aid increases bilateral trade flows in both directions. Our interpretation is that an intensified aid relation reduces the effective cost of geographic distance. We find a particularly strong relation between aid in the form of technical assistance and exports in both directions. When we disaggregate aid to specif- ically study the effects from trade-related assistance (Aid for Trade) the effect is small and fully accounted for by aid to investments in trade-related infras- tructure. Our sample includes all 184 countries for which data is available during the period 1990 to 2005. JEL Classification: F35; O19; O24 Keywords: Foreign Aid, International Trade, Exports, Gravity, Aid for Trade ∗The authors wish to thank Harry Flam and Pehr-Johan Norb¨ack for insightful comments. -

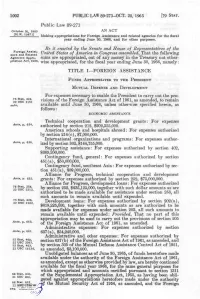

79 Stat. 1002

1002 PUBLIC LAW 89-273-OCT. 20, 1965 [79 STAT. Public Law 89-273 October 20, 1965 AN ACT [H. R. 10871] Making appropriations for Foreign Assistance and related agencies for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1966, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Eepresentatives of the Foreign Assist ance and Related United States of America in Congress assembled, That the following Agencies Appro sums are appropriated, out of any money in the Treasury not other priation Act, 1966. wise a])propriated, for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1966, namely: TITLE I—FOREIGN ASSISTANCE FUNDS APPROPRIATED TO THE PRESIDENT MUTUAL DEFENSE AND DEVELOPMENT For expenses necessary to enable the President to carry out the pro 75 Stat. 424, 22 use 2151 visions of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, to remain note. available until June 30, 1966, unless otherwise specified herein, as follows: ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE Technical cooperation and development grants: For expenses Ante, p. 654. authorized by section 212, $202,355,000. American schools and hospitals abroad: For expenses authorized by section 214(c), $7,000,000. International organizations and programs: For expenses author Ante, p. 656. ized by section 302, $144,755,000. Supporting assistance: For expenses authorized by section 402, $369,200,000. Contingency fund, general: For expenses authorized by section 451(a), $50,000,000. Contingency fund, southeast Asia: For expenses authorized by sec tion 451(a), $89,000,000. Alliance for Progress, technical cooperation and development Ante, p. 655. grants: For expenses authorized by section 252, $75,000,000. -

National Interests and the Paradox of Foreign Aid Under Austerity: Conservative Governments and the Domestic Politics of International Development Since 2010

National interests and the paradox of foreign aid under austerity: Conservative governments and the domestic politics of international development since 2010 Keywords: foreign aid: DfID; Conservatives; austerity; Brexit; national interest Acknowledgments: the ideas underpinning this paper have been informally discussed with a wide variety of colleagues, and I am grateful for their insights, although none are implicated in the final product. I would particularly like to thank the organisers (Nadia Molenaers, Joerg Faust and Jeroen Joly) and participants at ‘The Domestic Dimensions of Development Cooperation’, a conference at the Institute of Development Policy and Management University of Antwerp, Belgium October 24–25, 2016 Abstract Since 2010, successive Conservative-led Coalition and Conservative governments in the UK have imposed domestic austerity while maintaining foreign aid commitments. They have done so in the teeth of considerable hostility from influential sections of the media, many Conservative MPs and party members, and large sections of the voting public. This paper explains this apparently paradoxical position by analysing these governments’ increasingly explicit stance that aid serves ‘the national interest’ in a variety of ways. While not a new message from donors, post-2010 Conservative governments have significantly strengthened this narrative, with the (uncertain) intent of legitimising foreign aid expenditure. Introduction In 2010 a Conservative-led coalition with the Liberal Democrats displaced ‘New Labour’ from government in the United Kingdom after 13 years in power. In 2014, the Conservative Party achieved a narrow electoral majority to become the sole party of government. In 2016, following the Brexit referendum, a new Conservative government was formed under Prime Minister Theresa May. -

The Developmental Effectiveness of Untied Aid

Evaluation of the implementation of the Paris Declaration The Developmental Effectiveness of Untied Aid (1) Thematic Study The Developmental Effectiveness of Untied Aid: Evaluation of The Developmental the Implementation of the Paris Declaration and of the 2001 DAC Recommendation on Untying ODA to the LDCs Effectiveness Phase I Report of Untied Aid (1) This report presents the results of Phase I of a thematic study being un- dertaken within the framework of the Evaluation of the Paris Declaration, and in response to the request for an evaluation in the 2001 DAC recom- mendation to untie ODA to the LDCs. A second phase comprising field studies will be conducted in 2009. October 2008 Ownership, Alignment, Harmonisation, Results and Accountability Evaluation of the Paris Declaration thematic-omslag.indd 1 26/11/08 17:31:26 THEMATIC STUDY THE DEVELOPMENTAL EFFECTIVENESS OF UNTIED AID: EVALUATION OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PARIS DECLARATION AND OF THE 2001 DAC RECOMMENDA- TION ON UNTYING ODA TO THE LDCs Phase One Report ISBN: 978-87-7087-071-9 e-ISBN: 978-87-7087-072-6 © Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark Suggested citation: Clay, Edward J., Matthew Geddes, Luisa Natali and Dirk Willem te Velde Thematic Study, The Developmental Effectiveness of Untied Aid: Evaluation of the Implementation of the Paris Declaration and of the 2001 DAC Recommendation on Untying ODA To The LDCs, Phase I Report. Copenhagen, December 2008. Photocopies of all parts of this publication may be made providing the source is acknowledged. Graphic Design (Cover): ph7 kommunikation, www.ph7.dk Print: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Printing Office The report can be downloaded directly from http:///www.oecd.org/dac/evaluationnetwork and ordered free of charge online at www.