Baseball Free Agency and Salary Arbitration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

Nfl Anti-Tampering Policy

NFL ANTI-TAMPERING POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. DEFINITION ............................................................................... 2 Section 2. PURPOSE .................................................................................... 2 Section 3. PLAYERS ................................................................................. 2-8 College Players ......................................................................................... 2 NFL Players ........................................................................................... 2-8 Section 4. NON-PLAYERS ...................................................................... 8-18 Playing Season Restriction ..................................................................... 8-9 No Consideration Between Clubs ............................................................... 9 Right to Offset/Disputes ............................................................................ 9 Contact with New Club/Reasonableness ..................................................... 9 Employee’s Resignation/Retirement ..................................................... 9-10 Protocol .................................................................................................. 10 Permission to Discuss and Sign ............................................................... 10 Head Coaches ..................................................................................... 10-11 Assistant Coaches .............................................................................. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 8 Article 12 Issue 2 Spring Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law J. Gordon Hylton Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation J. Gordon Hylton, Book Review: Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law, 8 Marq. Sports L. J. 455 (1998) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol8/iss2/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS LEGAL BASES: BASEBALL AND THE LAW Roger I. Abrams [Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Temple University Press 1998] xi / 226 pages ISBN: 1-56639-599-2 In spite of the greater popularity of football and basketball, baseball remains the sport of greatest interest to writers, artists, and historians. The same appears to be true for law professors as well. Recent years have seen the publication Spencer Waller, Neil Cohen, & Paul Finkelman's, Baseball and the American Legal Mind (1995) and G. Ed- ward White's, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903-1953 (1996). Now noted labor law expert and Rutgers-Newark Law School Dean Roger Abrams has entered the field with Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law. Unlike the Waller, Cohen, Finkelman anthology of documents and White's history, Abrams does not attempt the survey the full range of intersections between the baseball industry and the legal system. In- stead, he focuses upon the history of labor-management relations. -

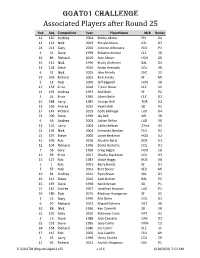

GOAT01 Challenge Associated Players After Round 25

GOAT01 Challenge Associated Players after Round 25 Rnd Seq Competitor Year PlayerName MLB Roster 14 120 Andrea 2004 Bobby Abreu PHI O4 14 124 Nick 2019 Ronald Acuna ATL O2 24 213 Gary 2000 Antonio Alfonseca FLO P3 4 31 Dave 1999 Roberto Alomar CLE 2B 10 86 Richard 2016 Jose Altuve HOU 2B 16 142 Nick 1996 Brady Anderson BAL O4 15 128 Steve 2016 Nolan Arenado COL 3B 6 52 Nick 2015 Jake Arrieta CHC S3 23 203 Richard 2001 Rich Aurilia SF MI 2 18 Rob 2000 Jeff Bagwell HOU 1B 17 153 Ernie 2018 Trevor Bauer CLE S3 22 192 Andrea 1993 Rod Beck SF P2 5 45 Ernie 1995 Albert Belle CLE O2 21 188 Larry 1987 George Bell TOR U2 19 169 Andrea 2010 Heath Bell SD R2 17 149 Richard 2019 Cody Bellinger LAD O4 23 200 Steve 1999 Jay Bell ARI 2B 6 48 Andrea 2004 Adrian Beltre LAD 3B 13 116 Larry 2004 Carlos Beltran 2Tms O5 22 196 Nick 2004 Armando Benitez FLO R2 22 197 Steve 2006 Lance Berkman HOU U2 13 109 Rob 2018 Mookie Betts BOS U1 12 104 Richard 1996 Dante Bichette COL O1 7 58 Gary 1998 Craig Biggio HOU 2B 11 99 Ernie 2017 Charlie Blackmon COL O3 15 127 Rob 1987 Wade Boggs BOS 3B 1 1 Rob 2001 Barry Bonds SF O1 7 57 Nick 2001 Bret Boone SEA MI 10 84 Andrea 2012 Ryan Braun MIL O2 16 143 Steve 2016 Zack Britton BAL P2 16 139 Dave 1998 Kevin Brown SD P1 21 187 Andrea 2007 Jonathan Broxton LAD P1 20 180 Rob 2015 Madison Bumgarner SF S2 2 15 Gary 1996 Ellis Burks COL O2 6 50 Richard 2012 Miguel Cabrera DET 3B 10 88 Nick 1996 Ken Caminiti SD 3B 22 195 Gary 2010 Robinson Cano NYY U2 2 13 Dave 1988 Jose Canseco OAK O2 25 218 Steve 1985 Gary Carter NYM C2 18 158 -

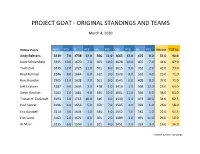

Project Goat - Original Standings and Teams

PROJECT GOAT - ORIGINAL STANDINGS AND TEAMS March 4, 2020 Hitting Points AVG PTS R PTS HR PTS RBI PTS SB PTS Hitting TOTAL Andy Behrens .3219 7.0 1738 12.0 566 11.0 1665 12.0 425 9.0 51.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield .3295 10.0 1670 7.0 563 10.0 1628 10.0 407 7.0 44.0 87.0 Todd Zola .3339 12.0 1725 11.0 551 8.0 1615 9.0 352 2.0 42.0 73.0 Brad Kullman .3246 8.0 1664 6.0 512 3.0 1579 8.0 362 4.0 29.0 71.0 Ron Shandler .3305 11.0 1628 3.0 561 9.0 1545 6.0 408 8.0 37.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson .3287 9.0 1605 2.0 478 1.0 1410 1.0 508 12.0 25.0 63.0 Steve Gardner .3161 1.0 1681 9.0 596 12.0 1661 11.0 366 5.0 38.0 63.0 Tristan H. Cockcroft .3193 3.0 1713 10.0 546 6.0 1530 5.0 473 10.0 34.0 62.5 Paul Sporer .3196 4.0 1653 5.0 550 7.0 1505 4.0 392 6.0 26.0 58.0 Eric Karabell .3214 5.0 1644 4.0 543 5.0 1552 7.0 342 1.0 22.0 51.5 Eno Sarris .3163 2.0 1671 8.0 504 2.0 1489 3.0 491 11.0 26.0 50.0 AJ Mass .3215 6.0 1599 1.0 521 4.0 1451 2.0 353 3.0 16.0 36.0 *Sorted by final standings Pitching Points W PTS SV PTS K PTS ERA PTS WHIP PTS Pitching TOTAL Andy Behrens 187 11.5 0 1.5 2348 12.0 1.98 9.0 0.90 9.0 43.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield 187 11.5 0 1.5 2288 11.0 1.95 11.0 0.91 8.0 43.0 87.0 Todd Zola 150 7.0 104 4.0 2154 8.0 2.03 7.0 0.95 5.0 31.0 73.0 Brad Kullman 141 4.5 141 10.5 1941 3.0 1.84 12.0 0.90 12.0 42.0 71.0 Ron Shandler 141 4.5 141 10.5 1886 2.0 1.97 10.0 0.93 7.0 34.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson 151 8.0 112 6.0 2130 6.0 2.01 8.0 0.90 10.0 38.0 63.0 Steve Gardner 147 6.0 105 5.0 2152 7.0 2.06 5.0 0.98 2.0 25.0 63.0 Tristan H. -

Developing a Metric to Evaluate the Performances of NFL Franchises In

Developing a Metric to Evaluate the Performance of NFL Franchises in Free Agency Sampath Duddu, William Wu, Austin Macdonald, Rohan Konnur University of California - Berkeley Abstract This research creates and offers a new metric called Free Agency Rating (FAR) that evaluates and compares franchises in the National Football League (NFL). FAR is a measure of how good a franchise is at signing unrestricted free agents relative to their talent level in the offseason. This is done by collecting and combining free agent and salary information from Spotrac and player overall ratings from Madden over the last six years. This research allowed us to validate our assumptions about which franchises are better in free agency, as we could compare them side to side. It also helped us understand whether certain factors that we assumed drove free agent success actually do. In the future, this research will help teams develop better strategies and help fans and analysts better project where free agents might go. The results of this research show that the single most significant factor of free agency success is a franchise’s winning culture. Meanwhile, factors like market size and weather, do not correlate to a significant degree with FAR, like we might anticipate. 1 Motivation NFL front offices are always looking to build balanced and complete rosters and prepare their team for success, but often times, that can’t be done without succeeding in free agency and adding talented veteran players at the right value. This research will help teams gain a better understanding of how they compare with other franchises, when it comes to signing unrestricted free agents. -

F(Error) = Amusement

Academic Forum 33 (2015–16) March, Eleanor. “An Approach to Poetry: “Hombre pequeñito” by Alfonsina Storni”. Connections 3 (2009): 51-55. Moon, Chung-Hee. Trans. by Seong-Kon Kim and Alec Gordon. Woman on the Terrace. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press, 2007. Peraza-Rugeley, Margarita. “The Art of Seen and Being Seen: the poems of Moon Chung- Hee”. Academic Forum 32 (2014-15): 36-43. Serrano Barquín, Carolina, et al. “Eros, Thánatos y Psique: una complicidad triática”. Ciencia ergo sum 17-3 (2010-2011): 327-332. Teitler, Nathalie. “Rethinking the Female Body: Alfonsina Storni and the Modernista Tradition”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America 79, (2002): 172—192. Biographical Sketch Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley is an Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of English, Foreign Languages and Philosophy at Henderson State University. Her scholarly interests center on colonial Latin-American literature from New Spain, specifically the 17th century. Using the case of the Spanish colonies, she explores the birth of national identities in hybrid cultures. Another scholarly interest is the genre of Latin American colonialist narratives by modern-day female authors who situate their plots in the colonial period. In 2013, she published Llámenme «el mexicano»: Los almanaques y otras obras de Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (Peter Lang,). She also has published short stories. During the summer of 2013, she spent time in Seoul’s National University and, in summer 2014, in Kyungpook National University, both in South Korea. https://www.facebook.com/StringPoet/ The Best Players in New York Mets History Fred Worth, Ph.D. -

Vo Cguantanamo Bay, Cuba

__ vo CGuantanamo Bay, Cuba Vol. 42 -- No. 123 -- U.S. Navy's only shore-based daily newspaper -- Monday, June 30, 1986 I. I South African trade leader detained Civil rights activists say political rally since ' PI)y the -- leaderDissident of sourcesSouth about 4,000 people have been emergency rule was imposed Around the globe Africa's largest trade union detained without charge under June 12. federation is being detained, the emergency. The Also, there are reports apparently to frustrate plans independent labor monitoring that up to five people were for black labor action to group says 923 unionists, 183 killed in fighting between protest emergency rule. leaders and 740 workers, are Zulu tribesman loyal to the Truck Drops Into Canyon (UPI) -- A pickup truck Dissidents say the leader among those held. chief and opponents at a carrying an unknown number of people swerved off an of the Congress of South At least one person was hostel in Someto. Arizona highway and dropped 1,000 feet into the Grand African Trade Unions was killed and 34 hurt yesterday A government spokesman says Canyon. Authorities say there was no sign of life in picked up Friday and detained when radical blacks attacked police fired at youths the twisted wreckage. A witness says a car cut in front without charge under buses leaving a Someto attacking the home of a of the pickup and the truck swerved to avoid a emergency powers. The sources Stadium where a moderate Zulu moderate black councilman, collision before plunging into the canyon. say the detention could last chief held a rally. -

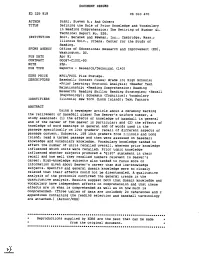

Defining the Role of Prior Knowledge and Vocabulary in Reading Comprehension: the Retiring of Number 41

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 919 CS 010 470 AUTHOR Stahl, Steven A.; And Others TITLE Defining the Role of Prior Knowledge and Vocabulary in Reading Comprehension: The Retiring of Number 41. Technical Report No. 526. INSTITUTION Bolt, Beranek and Newman, Inc., Cambridge, Mass.; Illinois Univ., Urbana. Center for the Study of Reading. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE Apr 91 CONTRACT G0087-C1001-90 NOTE 25p. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Baseball; Context Clues; Grade 10; High Schools; *Prior Learning; Protocol Analysis; *Reader Text Relationship; *Reading Comprehension; Reading Research; Reading Skills; Reading Strategies; *Recall (Psychology); Schemata (Cognition); Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Illinois; New York (Long Island); Text Factors ABSTRACT Using a newspaper article about a ceremony marking the retirement of baseball player Tom Seaver's uniform number,a study examined: (1) the effects of knowledge of baseballin general and of the career of Tom Seaver in particular; and (2) the effects of knowledge of word meanings in general and of words used in the passage specifically on 10th graders' recall of different aspects of passage content. Subjects, 159 10th graders from Illinois and Long Island, read a target passage and then were assessedon baseball knowledge and vocabulary knowledge. Vocabulary knowledge tendedto affect the number of units recalled overall, whereas prior knowledge influenced which units were recalled. Prior topic knowledge influenced whether subjects produced a "gist" statement in their recall and how well they recalled numbers relevant to Seaver's career. High-knowledge subjects also tended to focus moreon information given about Seaver's career than did low-knowledge subjects. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig