Social Television Viewing with Second Screen Platforms: Antecedents and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaboratv: Making Television Viewing Social Again

CollaboraTV: Making Television Viewing Social Again Mukesh Nathan Chris Harrison Svetlana Yarosh University of Minnesota Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Inst. of Technology [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Loren Terveen Larry Stead Brian Amento University of Minnesota AT&T Research Labs AT&T Research Labs [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT was first collected, a 50% increase since the 1950s, and a 12% With the advent of video-on-demand services and digital increase from 1996. The average person watches 4.5 hours video recorders, the way in which we consume media is un- of programming a day, with the average household tuned in dergoing a fundamental change. People today are less likely for more than 8 hours [10]. to watch shows at the same time, let alone the same place. Given the significant place that television holds in our As a result, television viewing, which was once a social ac- daily lives, our research focuses on understanding the so- tivity, has been reduced to a passive and isolated experience. cial aspects of television viewing – especially in today’s age To study this issue, we developed a system called Collabo- of social behavior-altering technological advances – and the raTV and demonstrated its ability to support the communal utility of social television systems for meeting the new chal- viewing experience through a month-long field study. Our lenges that such advances bring about. study shows that users understand and appreciate the utility of asynchronous interaction, are enthusiastic about Collabo- Declined Social Interactions Around Television raTV’s engaging social communication primitives and value Television was once championed as the “electronic hearth” implicit show recommendations from friends. -

Playstation®4 Launches Across the United States

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PLAYSTATION®4 LAUNCHES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA With the PS4™system, Sony Computer Entertainment Welcomes Gamers to a New Era of Rich, Immersive Gameplay Experiences TOKYO, November 15, 2013 – Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) today launched PlayStation®4 (PS4™), a system built for gamers and inspired by developers. The PS4 system is now available in the United States and Canada at a suggested retail price of USD $399 and CAD $399, arriving with a lineup of over 20 first- and third-party games, including exclusive titles like Knack™ and Killzone: Shadow Fall™. In total, the PS4 system will have a library of over 30 games by the end of the year. *1 “Today’s launch of PS4 represents a milestone for all of us at PlayStation, our partners in the industry, and, most importantly, all of the PlayStation fans who live and breathe gaming every day,” said Andrew House, President and Group CEO, Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. “With unprecedented power, deep social capabilities, and unique second screen features, PS4 demonstrates our unwavering commitment to delivering phenomenal play experiences that will shape the world of games for years to come.” The PS4 system enables game developers to realize their creative vision on a platform specifically tuned to their needs, making it easier to build huge, interactive worlds in smooth 1080p HD resolution.*2 Its supercharged PC architecture – including an enhanced Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) and 8GB of GDDR5 unified system memory – is designed to ease game creation and deliver a dramatic increase in the richness of content available on the platform. -

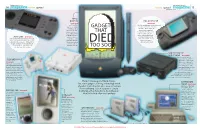

Gadgets That Too Soon

14 centre spread centre spread 15 DECEMBER 07-13, 2014 DECEMBER 07-13, 2014 APPLE NEWTON SEGA GAME GEAR It was a personal This 8-bit handheld game console was released digital assistant (PDA) GADGETS in response to Nintendo's Game Boy. It before palm and a was held lengthwise at the sides tablet before the iPad. (preventing the cramping of By modern standards, THAT hands) and had a backlit, colour it was pretty basic — it LCD screen, allowing for clearer could take notes, store and more vibrant visuals. It was ATARI LYNX contacts, and manage also praised for its processing Atari’s little handheld sported the rst colour LCD, calendars. It had a power. Its unique game library before Sega’s Game Gear, and was cheaper with stylus, and could even and price point gave it an better battery life in comparison. It ultimately lost translate handwriting edge over its competitors the game to Nintendo. It was nearly twice the into text. It could also DIED size of Game Boy's postage stamp screen be used to send a fax and oered much better graphics TOO SOON 3DO INTERACTIVE MULTIPLAYER Manufactured by Panasonic, Sanyo and GoldStar, 3DO was SEGA DREAMCAST the rst game system to use CDs for content delivery. The It was superior to most other increase in data storage led to syst ems at the time with built-in better 3D graphics. Also, the modem for Internet support and gaming machine was one of the online play as well as a controller rst entries in the 32-bit that allowed second-screen gaming. -

Second Screen Interaction in the Cinema: Experimenting with Transmedia Narratives and Commercialising User Participation

. Volume 14, Issue 2 November 2017 Second Screen interaction in the cinema: Experimenting with transmedia narratives and commercialising user participation James Blake, Edinburgh Napier University, UK Abstract: In its relatively short life, second screen interaction has evolved into a variety of forms of viewer engagement. The practice of using two screens concurrently has become common in domestic TV viewing but remains a relatively specialist and niche experience in movie theatres. For this paper, three case studies explore the motivations and challenges involved in such projects. The film Late Shift (Weber, 2016) pulls together conventional cinematic narrative techniques and combines them with the interactivity of Full Motion Video games. An earlier film, App (Boermans, 2015) innovated with the second screen as a vehicle for transmedia content to enhance an affective response within the horror genre. The release of the film Angry Birds (Rovio, 2016) involved a symbiotic second screen play-along element which began in advance of the screening and continued after the movie concluded. This study also analyses other interactive projects within this context, including Disney’s short- lived ‘Second Screen Live’ that accompanied the release of The Little Mermaid (Disney, 1993) and commercial platforms including CiniMe and TimePlay. Mobile devices are being used as platforms for interactive gameplay, social participation and commercial opportunities. However, this landscape has implications on the culture of audience etiquette and the notion of user agency within an environment of immersive storytelling. Keywords: Interaction; Immersion; Transmedia (Narratives); Agency; Distraction; Paratext Introduction The concept of the ‘second screen’ is a relatively recent addition in the lexicon of audience reception studies and media analysis. -

Post-Broadcast TV Content Consumption Patterns - a Research Into Contemporary Croatian Consumers’ Viewing Habits

Coll. Antropol. 43 (2019) 4: 1–XXX Original scientific paper Post-Broadcast TV Content Consumption Patterns - A Research into Contemporary Croatian Consumers’ Viewing Habits Darijo Čerepinko, Željka Bagarić, Lidija Dujić Department for Public Relations, University “North”, Varaždin, Croatia ABSTRACT In the post-broadcast television era marked by technology convergence content consumption has undergone major transformations and that process is still ongoing. With the digital age, multiple new opportunities to watch television content on different devices, in different places and in changed social surrounding have opened up. Different devices, such as tablets and smartphones, have become integrated into the content consumption behavior and have even become the main device used for television or on demand content consumption. Consumers are migrating to streaming and on demand services, and traditional media adapt to the new pace of changing viewer habits. The constant audience transformation shows that multiscreen living rooms are turning into many single screen rooms through the usage of individual digital devices as they become the primary source of content consumption. In order to understand the trends that are changing at a fast pace, this paper will look into different aspects of new media consumption trends through quantitative research. Understanding the current consumer preferences in the latest digital technological shift is an important element that helps shape television program production, distribution and marketing decisions. Key words: technology convergence, television, new media, content, digital age Introduction In the era of technology convergence content consump- Recent research in the industry and the academia is tion has undergone major transformations. The digital focused on the development of new patterns of content age has opened up multiple new opportunities to watch consumptions. -

The Complete Guide to Social Media from the Social Media Guys

The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Nov 2010 19:01:07 UTC Contents Articles Social media 1 Social web 6 Social media measurement 8 Social media marketing 9 Social media optimization 11 Social network service 12 Digg 24 Facebook 33 LinkedIn 48 MySpace 52 Newsvine 70 Reddit 74 StumbleUpon 80 Twitter 84 YouTube 98 XING 112 References Article Sources and Contributors 115 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 125 Social media 1 Social media Social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable publishing techniques. Social media uses web-based technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein define social media as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, which allows the creation and exchange of user-generated content."[1] Businesses also refer to social media as consumer-generated media (CGM). Social media utilization is believed to be a driving force in defining the current time period as the Attention Age. A common thread running through all definitions of social media is a blending of technology and social interaction for the co-creation of value. Distinction from industrial media People gain information, education, news, etc., by electronic media and print media. Social media are distinct from industrial or traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and film. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible to enable anyone (even private individuals) to publish or access information, compared to industrial media, which generally require significant resources to publish information. -

Social TV Engagement for Increasing and Sustaining Social TV Viewers

sustainability Article Social TV Engagement for Increasing and Sustaining Social TV Viewers Odukorede Odunaiya *, Mary Agoyi and Oseyenbhin Sunday Osemeahon Department of Management Information Systems, School of Applied Sciences, Cyprus International University, 99258 Nicosia, Turkey; [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (O.S.O.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 April 2020; Accepted: 4 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: With little known about how social TV (STV) strategies can be harnessed by the broadcasting industry in order to increase and sustain their viewers, this study brings new insight to the social TV phenomenon by investigating the effect of game uncertainty and social media use (SMU) on social TV engagement in generating network loyalty (NL). The study also analyzed the mediating effect of severity between game uncertainty and social media use with social TV engagement. SmartPLS 3 was used to analyze the survey data of 364 participants for the proposed model, and the findings from the study revealed that game uncertainty and social media use have a positive effect on social TV engagement, which positively influences network loyalty. In addition, it was seen that severity mediates the relationship between game uncertainty and social media use with social TV engagement. Keywords: social TV; game uncertainty; perceived severity; social media; social media use; social TV engagement; network loyalty 1. Introduction Social television is the union of television and social media. This has encouraged a massive rise in connectivity and content engagement among TV viewers via social media interactions [1]. Millions of people now share their TV experience with others on online social networking platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. -

Exploring Social Media Scenarios for the Television

Exploring Social Media Scenarios for the Television Noor F. Ali-Hasan Microsoft 1065 La Avenida Street Mountain View, CA 94043 [email protected] Abstract social media currently fits in participants‟ lives, gauge their The use of social technologies is becoming ubiquitous in the interest in potential social TV features, and understand lives of average computer users. However, social media has their concerns for such features. This paper discusses yet to infiltrate users‟ television experiences. This paper related research in combining TV and social technologies, presents the findings of an exploratory study examining presents the study‟s research methods, introduces the social scenarios for TV. Eleven participants took part in the participants and their defining characteristics, and three-part study that included in-home field visits, a diary summarizes the study‟s findings in terms of the study of participants‟ daily usage of TV and social media, participants‟ current TV and social media usage and their and participatory design sessions. During the participatory interest in social scenarios for the TV. design sessions, participants evaluated and discussed several paper wireframes of potential social TV applications. Overall, participants responded to most social TV concepts with excitement and enthusiasm, but were leery of scenarios Related Work that they felt violated their privacy. In recent years, a great deal of research has been conducted around the use of blogs and online social networks. Studies exploring social television applications have been Introduction fewer in number, likely due to the limited availability of Whether in the form of blogs or online social networks, such applications in consumers‟ homes. -

LINEAR TV in the NON-LINEAR WORLD the Value of Linear

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Drexel Libraries E-Repository and Archives LINEAR TV IN THE NON-LINEAR WORLD The Value of Linear Scheduling Amidst the Proliferation of Non-Linear Platforms A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Carlo Angelo Mandala Hernandez in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Television Management March 2017 © Copyright 2017 Carlo Angelo Mandala Hernandez. All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge and express my appreciation for the individuals and groups who helped to make this thesis a possibility, and who encouraged me to get this done. To my thesis adviser Phil Salas and program director Albert Tedesco, thank you for your guidance and for all the good words. To all the participants in this thesis, Jeff Bader, Dan Harrison, Kelly Kahl, Andy Kubitz, and Dennis Goggin, thank you for sharing your knowledge and experience. Without you, this research study would lack substance or would not have materialized at all. I would also like to extend my appreciation to those who helped me to reach out to network executives and set up interview schedules: Nancy Robinson, Anthony Maglio, Omar Litton, Mary Clark, Tamara Sobel and Elle Berry Johnson. I would like to thank the following for their insights, comments and suggestions: Elizabeth Allan-Harrington, Preston Beckman, Yvette Buono, Eric Cardinal, Perry Casciato, Michelle DeVylder, Larry Epstein, Kevin Levy, Kimberly Luce, Jim -

Conceptualizing Television Viewing in the Digital Age: Patterns of Exposure and the Cultivation Process

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2018 Conceptualizing television viewing in the digital age: Patterns of exposure and the cultivation process Lisa Prince University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Prince, Lisa, "Conceptualizing television viewing in the digital age: Patterns of exposure and the cultivation process" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1186. https://doi.org/10.7275/11216509.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1186 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONCEPTUALIZING TELEVISION VIEWING IN THE DIGITAL AGE: PATTERNS OF EXPOSURE AND THE CULTIVATION PROCESS A Dissertation Presented by LISA PRINCE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2018 Communication © Copyright by Lisa Prince 2018 All Rights Reserved CONCEPTUALIZING TELEVISION VIEWING IN THE DIGITAL AGE: PATTERNS OF EXPOSURE AND THE CULTIVATION PROCESS A Dissertation Presented by LISA PRINCE Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ -

New Joysticks Available for Your Atari 2600

May Your Holiday Season Be a Classic One Classic Gamer Magazine Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 3 The Xonox List 27 Teach Your Children Well 28 Games of Blame 29 Mit’s Revenge 31 The Odyssey Challenger Series 34 Interview With Bob Rosha 38 Atari Arcade Hits Review 41 Jaguar: Straight From the Cat’s 43 Mouth 6 Homebrew Review 44 24 Dear Santa 46 CGM Online Reset 5 22 So, what’s Happening with CGM Newswire 6 our website? Upcoming Releases 8 In the coming months we’ll Book Review: The First Quarter 9 be expanding our web pres- Classic Ad: “Fonz” from 1976 10 ence with more articles, games and classic gaming merchan- Lost Arcade Classic: Guzzler 11 dise. Right now we’re even The Games We Love to Hate 12 shilling Classic Gamer Maga- zine merchandise such as The X-Games 14 t-shirts and coffee mugs. Are These Games Unplayable? 16 So be sure to check online with us for all the latest and My Favorite Hedgehog 18 greatest in classic gaming news Ode to Arcade Art 20 and fun. Roland’s Rat Race for the C-64 22 www.classicgamer.com Survival Island 24 Head ‘em Off at the Past 48 Classic Ad: “K.C. Munchkin” 1982 49 My .025 50 Make it So, Mr. Borf! Dragon’s Lair 52 and Space Ace DVD Review How I Tapped Out on Tapper 54 Classifieds 55 Poetry Contest Winners 55 CVG 101: What I Learned Over 56 Summer Vacation Atari’s Misplays and Bogey’s 58 46 Deep Thaw 62 38 Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 4 “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to Issue 5 repeat it” - George Santayana December 2000 Editor-in-Chief “Unfortunately, those of us who do remember the past are Chris Cavanaugh condemned to repeat it with them." - unaccredited [email protected] Managing Editor -Box, Dreamcast, Play- and the X-Box? Well, much to Sarah Thomas [email protected] Station, PlayStation 2, the chagrin of Microsoft bashers Gamecube, Nintendo 64, everywhere, there is one rule of Contributing Writers Indrema, Nuon, Game business that should never be X Mark Androvich Boy Advance, and the home forgotten: Never bet against Bill. -

Effects of Social Media on Content of Local

EFFECTS OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON CONTENT OF LOCAL TELEVISION PROGRAMS IN KENYA: A CASE STUDY OF CITIZEN TV’S GOSPEL SUNDAY SHOW BY NATHANIEL COLLINS OUMA K50/68883/2011 A RESEARCH PROJECT PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN COMMUNICATION STUDIES, SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2013 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for award of degree in any other University. NATHANIEL COLLINS OUMA K50/68883/2011 Signed: __________________________ Date ___________________ This proposal has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University supervisor. DAVIS MOKAYA SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION Signed: __________________________ Date ___________________ i DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family Mr. and Mrs. Olali, my siblings Elvis, Kennedy and Brian. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I acknowledge the Almighty God for giving me good health through the duration of my studies. His love and profound protection saw me accomplish this achievement. I sincerely thank the profound support of my supervisor Mr. Davis Mokaya for his dedication and guidance during the entire period of my research. He took time off his busy schedule to share his immense knowledge of the field of social media and technology. I particularly thank him for his immense support from the inception of the idea and subsequent development of the same through this stage of its completion. I would like to thank the entire Royal Media family and in particular Lillian Kiilu, Njugush and Kanze for their help. Similarly, I would like to thank my friends, classmates and colleagues for their moral support and encouragement.