Gas and Star Formation in the Circinus Galaxy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NGC 1333 Plunkett Et

Outflows in protostellar clusters: a multi-wavelength, multi-scale view Adele L. Plunkett1, H. G. Arce1, S. A. Corder2, M. M. Dunham1, D. Mardones3 1-Yale University; 2-ALMA; 3-Universidad de Chile Interferometer and Single Dish Overview Combination FCRAO-only v=-2 to 6 km/s FCRAO-only v=10 to 17 km/s K km s While protostellar outflows are generally understood as necessary components of isolated star formation, further observations are -1 needed to constrain parameters of outflows particularly within protostellar clusters. In protostellar clusters where most stars form, outflows impact the cluster environment by injecting momentum and energy into the cloud, dispersing the surrounding gas and feeding turbulent motions. Here we present several studies of very dense, active regions within low- to intermediate-mass Why: protostellar clusters. Our observations include interferometer (i.e. CARMA) and single dish (e.g. FCRAO, IRAM 30m, APEX) To recover flux over a range of spatial scales in the region observations, probing scales over several orders of magnitude. How: Based on these observations, we calculate the masses and kinematics of outflows in these regions, and provide constraints for Jy beam km s Joint deconvolution method (Stanimirovic 2002), CARMA-only v=-2 to 6 km/s CARMA-only v=10 to 17 km/s models of clustered star formation. These results are presented for NGC 1333 by Plunkett et al. (2013, ApJ accepted), and -1 comparisons among star-forming regions at different evolutionary stages are forthcoming. using the analysis package MIRIAD. -1 1212COCO Example: We mapped NGC 1333 using CARMA with a resolution of ~5’’ (or 0.006 pc, 1000 AU) in order to Our study focuses on Class 0 & I outflow-driving protostars found in clusters, and we seek to detect outflows and associate them with their driving sources. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Scutum Apus Aquarius Aquila Ara Bootes Canes Venatici Capricornus Centaurus Cepheus Circinus Coma Berenices Corona Austrina Coro

Polaris Ursa Minor Cepheus Camelopardus Thuban Draco Cassiopeia Mizar Ursa Major Lacerta Lynx Deneb Capella Perseus Auriga Canes Venatici Algol Cygnus Vega Cor Caroli Andromeda Lyra Bootes Leo Minor Castor Triangulum Corona Borealis Albireo Hercules Pollux Alphecca Gemini Vulpecula Coma Berenices Pleiades Aries Pegasus Sagitta Arcturus Taurus Cancer Aldebaran Denebola Leo Delphinus Serpens [Caput] Regulus Equuleus Altair Canis Minor Pisces Betelgeuse Aquila Procyon Orion Serpens [Cauda] Ophiuchus Virgo Sextans Monoceros Mira Scutum Rigel Aquarius Spica Cetus Libra Crater Capricornus Hydra Sirius Corvus Lepus Deneb Kaitos Canis Major Eridanus Antares Fomalhaut Piscis Austrinus Sagittarius Scorpius Antlia Pyxis Fornax Sculptor Microscopium Columba Caelum Corona Austrina Lupus Puppis Grus Centaurus Vela Norma Horologium Phoenix Telescopium Ara Canopus Indus Crux Pictor Achernar Hadar Carina Dorado Tucana Circinus Rigel Kentaurus Reticulum Pavo Triangulum Australe Musca Volans Hydrus Mensa Apus SampleOctans file Chamaeleon AND THE LONELY WAR Sample file STAR POWER VOLUME FOUR: STAR POWER and the LONELY WAR Copyright © 2018 Michael Terracciano and Garth Graham. All rights reserved. Star Power, the Star Power logo, and all characters, likenesses, and situations herein are trademarks of Michael Terracciano and Garth Graham. Except for review purposes, no portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the express written consent of the copyright holders. All characters and events in this publication are fictional and any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental. Star chartsSample adapted from charts found at hoshifuru.jp file Portions of this book are published online at www.starpowercomic.com. This volume collects STAR POWER and the LONELY WAR Issues #16-20 published online between Oct 2016 and Oct 2017. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Molecular Gas Conditions in NGC 4945 and the Circinus Galaxy?

A&A 367, 457–469 (2001) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20000462 & c ESO 2001 Astrophysics Molecular gas conditions in NGC 4945 and the Circinus galaxy? S. J. Curran1,2,L.E.B.Johansson1,P.Bergman1, A. Heikkil¨a1,3, and S. Aalto1 1 Onsala Space Observatory, Chalmers University of Technology, 439 92 Onsala, Sweden 2 European Southern Observatory, Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile 3 Observatory, PO Box 14, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Received 11 July 2000 / Accepted 5 December 2000 Abstract. We present results of a multi-transition study of the dense molecular gas in the central part of the hybrid star-burst/Seyfert galaxies NGC 4945 and the Circinus galaxy. From the results of radiative transfer 3− 4 −3 ≈ calculations, we estimate in NGC 4945 nH2 =310 10 cm and Tkin 100 K and in Circinus nH2 = 3 5 −3 210−10 cm and Tkin ≈ 50−80 K for the molecular hydrogen density and kinetic temperature, respectively. As well as density/temperature tracing molecules, we have observed C17OandC18O in each galaxy and the value of C18O/C17O ≈ 6 for the isotopic column density ratio suggests that both have relatively high populations of massive stars. Finally, although star formation is present, the radiative transfer results combined with the high HCN/CO and (possibly) HCN/FIR, radio/FIR ratios may suggest that, in comparison with Circinus, a higher proportion of the dense gas emission in NGC 4945 may be located in the hypothesised central nuclear disk as opposed to dense star forming cloud cores. Contrary to the literature, which assumes that all of the far-infrared emission arises from star formation, our results suggest that in NGC 4945 some of this emission could arise from an additional source, and so we believe that a revision of the star formation rate estimates may be required for these two galaxies. -

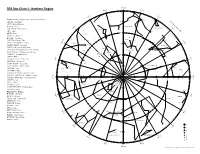

These Sky Maps Were Made Using the Freeware UNIX Program "Starchart", from Alan Paeth and Craig Counterman, with Some Postprocessing by Stuart Levy

These sky maps were made using the freeware UNIX program "starchart", from Alan Paeth and Craig Counterman, with some postprocessing by Stuart Levy. You’re free to use them however you wish. There are five equatorial maps: three covering the equatorial strip from declination −60 to +60 degrees, corresponding roughly to the evening sky in northern winter (eq1), spring (eq2), and summer/autumn (eq3), plus maps covering the north and south polar areas to declination about +/− 25 degrees. Grid lines are drawn at every 15 degrees of declination, and every hour (= 15 degrees at the equator) of right ascension. The equatorial−strip maps use a simple rectangular projection; this shows constellations near the equator with their true shape, but those at declination +/− 30 degrees are stretched horizontally by about 15%, and those at the extreme 60−degree edge are plotted twice as wide as you’ll see them on the sky. The sinusoidal curve spanning the equatorial strip is, of course, the Ecliptic −− the path of the Sun (and approximately that of the planets) through the sky. The polar maps are plotted with stereographic projection. This preserves shapes of small constellations, but enlarges them as they get farther from the pole; at declination 45 degrees they’re about 17% oversized, and at the extreme 25−degree edge about 40% too large. These charts plot stars down to magnitude 5, along with a few of the brighter deep−sky objects −− mostly star clusters and nebulae. Many stars are labelled with their Bayer Greek−letter names. Also here are similarly−plotted maps, based on galactic coordinates. -

Influence of Velocity Dispersions on Star-Formation Activities in Galaxies

A&A 641, A24 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202037748 & c T.-M. Wang and C.-Y. Hwang 2020 Astrophysics Influence of velocity dispersions on star-formation activities in galaxies? Tsan-Ming Wang ( )1,2,3 and Chorng-Yuan Hwang ( )3 1 Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 3 Graduate Institute of Astronomy, National Central University, No. 300, Zhongda Rd., Zhongli Dist., Taoyuan City 320, Taiwan Received 15 February 2020 / Accepted 15 June 2020 ABSTRACT We investigated the influence of the random velocity of molecular gas on star-formation activities of six nearby galaxies. The physical properties of a molecular cloud, such as temperature and density, influence star-formation activities in the cloud. Additionally, local and turbulent motions of molecules in a cloud may exert substantial pressure on gravitational collapse and thus prevent or reduce star formation in the cloud. However, the influence of gas motion on star-formation activities remains poorly understood. We used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array to obtain 12CO(J = 1−0) flux and velocity dispersion. We then combined these data with 3.6 and 8 micron midinfrared data from the Spitzer Space Telescope to evaluate the effects of gas motion on star- formation activities in several nearby galaxies. We discovered that relatively high velocity dispersion in molecular clouds corresponds with relatively low star-formation activity. Considering the velocity dispersion as an additional parameter, we derived a modified Kennicutt-Schmidt law with a gas surface density power index of 0.84 and velocity dispersion power index of −0.61. -

A Compendium of Distances to Molecular Clouds in the Star Formation Handbook?,?? Catherine Zucker1, Joshua S

A&A 633, A51 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936145 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics A compendium of distances to molecular clouds in the Star Formation Handbook?,?? Catherine Zucker1, Joshua S. Speagle1, Edward F. Schlafly2, Gregory M. Green3, Douglas P. Finkbeiner1, Alyssa Goodman1,5, and João Alves4,5 1 Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3 Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, Physics and Astrophysics Building, 452 Lomita Mall, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 4 University of Vienna, Department of Astrophysics, Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria 5 Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 10 Garden St, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Received 21 June 2019 / Accepted 12 August 2019 ABSTRACT Accurate distances to local molecular clouds are critical for understanding the star and planet formation process, yet distance mea- surements are often obtained inhomogeneously on a cloud-by-cloud basis. We have recently developed a method that combines stellar photometric data with Gaia DR2 parallax measurements in a Bayesian framework to infer the distances of nearby dust clouds to a typical accuracy of ∼5%. After refining the technique to target lower latitudes and incorporating deep optical data from DECam in the southern Galactic plane, we have derived a catalog of distances to molecular clouds in Reipurth (2008, Star Formation Handbook, Vols. I and II) which contains a large fraction of the molecular material in the solar neighborhood. Comparison with distances derived from maser parallax measurements towards the same clouds shows our method produces consistent distances with .10% scatter for clouds across our entire distance spectrum (150 pc−2.5 kpc). -

Parsec-Scale Bipolar X-Ray Shocks Produced by Powerful Jets from The

Draft version January 17, 2021 A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 11/10/09 PARSEC-SCALE BIPOLAR X-RAY SHOCKS PRODUCED BY POWERFUL JETS FROM THE NEUTRON STAR CIRCINUS X-1 P. H. Sell1, S. Heinz1, D. E. Calvelo2, V. Tudose3,4,5, P. Soleri6, R. P. Fender2, P. G. Jonker7,8,9, N. S. Schulz10, W. N. Brandt11, M. A. Nowak10, R. Wijnands12, M. van der Klis12, P. Casella2 Draft version January 17, 2021 ABSTRACT We report the discovery of multi-scale X-ray jets from the accreting neutron star X-ray binary, Circinus X-1. The bipolar outflows show wide opening angles and are spatially coincident with the radio jets seen in new high-resolution radio images of the region. The morphology of the emission regions suggests that the jets from Circinus X-1 are running into a terminal shock with the interstellar medium, as is seen in powerful radio galaxies. This and other observations indicate that the jets have a wide opening angle, suggesting that the jets are either not very well collimated or precessing. We interpret the spectra from the shocks as cooled synchrotron emission and derive a cooling age of 35 −1 37 −1 ∼ 1600 yr. This allows us to constrain the jet power to be 3 × 10 ergs . Pjet . 2 × 10 ergs , making this one of a few microquasars with a direct measurement of its jet power and the only known microquasar that exhibits stationary large-scale X-ray emission. Subject headings: ISM: jets and outflows, X-rays: binaries, X-rays: individual (Circinus X-1) 1. -

Community Plan for Far-IR/Submillimeter Space

This paper represents the consensus view of the 124 participants in the “Second Workshop on New Concepts for Far-Infrared/Submillimeter Space Astronomy,” which was held on 7 – 8 March 2002 in College Park, Maryland. The participants are listed below. Peter Ade Jason Glenn Marco Quadrelli Rachel Akeson Matthew Griffin Manuel Quijada Shafinaz Ali Martin Harwit Simon Radford Michael Amato Thomas Henning Jayadev Rajagopal Richard Arendt Ross Henry David Redding Charles Baker Stefan Heyminck Frank Rice Dominic Benford SamHollander Paul Richards Andrew Blain Joseph Howard George Rieke James Bock Wen-Ting Hsieh Stephen Rinehart Kirk Borne Mike Kaplan Cyrille Rioux Ray Boucarut Jeremy Kasdin Juan Roman Francois Boulanger Sasha Kashlinsky Goran Sandell Matt Bradford Alan Kogut Paolo Saraceno Susan Breon Alexander Kutyrev Rick Shafer Charles Butler Guilaine Lagache Peter Shirron Daniela Calzetti Brook Lakew Peter Shu Edgar Canavan Jean-Michel Lamarre Robert Silverberg Larry Caroff Charles Lawrence Howard Smith Edward Cheng Peter Lawson Johannes Staguhn Jay Chervenak David Leisawitz Phil Stahl Lucien Cox Dan Lester Carl Stahle William Danchi Charles F. Lillie Thomas Stevenson Ann Darrin Landis Markley John Storey Piet de Korte John Mather Guy Stringfellow Thijs de Graauw Mark Matsumura Keith Strong Bruce Dean Gary Melnick Mark Swain Mark Devlin Michael Menzel Peter Timbie Michael DiPirro David Miller Wes Traub Terence Doiron Sergio Molinari Charlotte Vastel Jennifer Dooley Harvey Moseley Thangasamy Velusamy Mark Dragovan Ronald Muller Christopher -

SFA Star Chart 1

Nov 20 SFA Star Chart 1 - Northern Region 0h Dec 6 Nov 5 h 23 30º 1 h d Dec 21 h p Oct 21h s b 2 h 22 ANDROMEDA - Daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia Mirach Local Meridian for 8 PM q m ANTLIA - Air Pumpe p 40º APUS - Bird of Paradise n o i b g AQUILA - Eagle k ANDROMEDA Jan 5 u TRIANGULUM AQUARIUS - Water Carrier Oct 6 h z 3 21 LACERTA l h ARA - Altar j g ARIES - Ram 50º AURIGA - Charioteer e a BOOTES - Herdsman j r Schedar b CAELUM - Graving Tool x b a Algol Jan 20 b o CAMELOPARDALIS - Giraffe h Caph q 4 Sep 20 CYGNUS k h 20 g a 60º z CAPRICORNUS - Sea Goat Deneb z g PERSEUS d t x CARINA - Keel of the Ship Argo k i n h m a s CASSIOPEIA - Ethiopian Queen on a Throne c h CASSIOPEIA g Mirfak d e i CENTAURUS - Half horse and half man CEPHEUS e CEPHEUS - Ethiopian King Alderamin a d 70º CETUS - Whale h l m Feb 5 5 CHAMAELEON - Chameleon h i g h 19 Sep 5 i CIRCINUS - Compasses b g z d k e CANIS MAJOR - Larger Dog b r z CAMELOPARDALIS 7 h CANIS MINOR - Smaller Dog e 80º g a e a Capella CANCER - Crab LYRA Vega d a k AURIGA COLUMBA - Dove t b COMA BERENICES - Berenice's Hair Aug 21 j Feb 20 CORONA AUSTRALIS - Southern Crown Eltanin c Polaris 18 a d 6 d h CORONA BOREALIS - Northern Crown h q g x b q 30º 30º 80º 80º 40º 70º 50º 60º 60º 70º 50º CRATER - Cup 40º i e CRUX - Cross n z b Rastaban h URSA CORVUS - Crow z r MINOR CANES VENATICI - Hunting Dogs p 80º b CYGNUS - Swan h g q DELPHINUS - Dolphin Kocab Aug 6 e 17 DORADO - Goldfish q h h h DRACO o 7 DRACO - Dragon s GEMINI t t Mar 7 EQUULEUS - Little Horse HERCULES LYNX z i a ERIDANUS - River j