A New English Keyboard Manuscript of the Seventeenth Century: Autograph Music by Draghi and Purcell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julian Marshall and the British Museum: Music Collecting in the Later Nineteenth Century

JULIAN MARSHALL AND THE BRITISH MUSEUM: MUSIC COLLECTING IN THE LATER NINETEENTH CENTURY ARTHUR SEARLE IN the second volume of Sir George Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians^ which appeared in 1880, there is a descriptive list of private music libraries in the British Isles.* First, understandably enough, is the Royal Music Library at Buckingham Palace; the next two libraries listed are those of Sir Arthur Frederick Gore Ouseley and of Mr Julian Marshall. The entire Royal Music Library is now in the British Library by royal gift; the whole of Ouseley's collection passed to his foundation of St Michael's College, Tenbury. These two libraries have been catalogued in some detail and both the process of their assembly and the personalities involved have been explored.^ Only two substantial parts of Marshall's collection remain intact: his printed Handel scores and libretti, now in the National Library of Scotland, and the major part of his manuscript music in the British Library.^ Marshall's name remains almost unknown, and to many musicologists his book- plate, which is still easy enough to encounter, complicates rather than simplifies the problem of provenance. The only source for the basic facts of Marshall's life is the brief notice of him given in the Dictionary of National Biography. He was born in Yorkshire in 1836, the younger son of an industrial and political family, was educated privately and at Harrow, and, for a while in the later 1850s, worked in the family flax spinning business. During those years he sang in the choir of Leeds parish church under Samuel Sebastian Wesley and played a part in the establishment ofthe first Leeds festival in 1858. -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 GMT TUESDAY, 5 APRIL 2016 Future Programme professional teams Lead Designer, Windsor Castle Purcell has been appointed to lead the multidisciplinary design team; advising, managing and coordinating the project from design concept to implementation. Purcell is a leading architectural practice with studios throughout the UK and in Asia Pacific. The practice is highly regarded for their heritage and design work within sensitive and complex sites. The practice has previously completed projects at Kensington Palace, Hampton Court Palace, Dover Castle, Wells Cathedral, the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich and Tower Bridge. Lead Designer, Palace of Holyroodhouse Set up by Catherine Burd & Buddy Haward in 1998, Burd Haward Architects has a reputation for making award-winning, carefully crafted, authentic, sustainable buildings. The practice works across a diverse range of building types and has led projects at a number of high-profile architecturally sensitive historic sites, including Chastleton House, Red House and Chartwell. Their new ‘Welcome Centre’ for the National Trust at Mottisfont Abbey in Hampshire is currently shortlisted for a 2016 RIBA Award. The design team includes: Exhibition Design – Nissen Richards Environmental Engineers – Max Fordham LLP Landscape Architects – J&L Gibbons Structural Engineers – David Narro Associates Cost Consultants Mace is an international consultancy and construction company, employing over 4,600 people, with a turnover of £1.49bn. Mace’s business is programme and project management, cost consultancy, construction delivery and facilities management. Mace has worked on projects at many high-profile listed buildings including The British Museum, the Parliamentary Estate and Senate House (School of Oriental and African Studies), Tate Modern Gallery and the Ashmolean Museum. -

Press Release Under Embargo Until 00:01, Thursday 8 April 2021

PRESS RELEASE UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 00:01, THURSDAY 8 APRIL 2021 THE NATIONAL GALLERY ANNOUNCES SIX SHORTLISTED DESIGN TEAMS FOR ITS NG200 PLANS The National Gallery has today (8 April 2021) announced six shortlisted design teams in its search for a partner to work with it on a suite of capital projects to mark its Bicentenary. An initial phase of work will be completed in 2024, to mark the Gallery’s 200th year. The shortlisted teams are: • Asif Khan with AKT II, Atelier Ten, Bureau Veritas, Donald Insall Associates, Donald Hyslop, Gillespies, Joseph Henry, Kenya Hara, and Plan A Consultants • Caruso St John Architects with Arup, Alan Baxter, muf architecture/art and Alliance CDM • David Chipperfield Architects with Publica, Expedition, Atelier Ten, iM2 and Plan A Consultants • David Kohn Architects with Max Fordham, Price & Myers, Purcell and Todd Longstaffe‐Gowan • Selldorf Architects with Purcell, Vogt Landscape Architects, Arup and AEA Consulting • Witherford Watson Mann Architects with Price and Myers, Max Fordham, Grant Associates, Purcell and David Eagle Ltd The shortlist has been drawn from an impressive pool of submissions from highly talented UK and international architect-led teams. In addition to members of the executive team and Trustees of the National Gallery, several independent panellists are advising on the selection process, which is being run by Malcolm Reading Consultants. These are Edwin Heathcote, Architecture Critic and Author; leading structural engineer Jane Wernick CBE FREng; and Ben Bolgar, Senior Design Director for the Prince’s Foundation. The extremely high quality of the submissions led the panel to increase the number shortlisted from the originally envisaged five, to six. -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown. -

2017/18 Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS AT 31 MARCH 2018 Trustees’ Report Trustees Rupert Gavin (Chairman) Zeinab Badawi Professor Sir David Cannadine Bruce Carnegie-Brown Ajay Chowdhury Liz Cleaver (until 26 May 2017) Baron Houghton of Richmond in the County of North Yorkshire Jane Kennedy Tim Knox FSA (from 5 March 2018) Sir Jonathan Marsden KCVO (until 21 December 2017) Carole Souter CBE Sir Michael Stevens KCVO Sue Wilkinson MBE (from 1 August 2017) M Louise Wilson FRSA Executive Board John Barnes (Chief Executive and Accounting Officer) since 1 July 2017 Michael Day CVO (Chief Executive and Accounting Officer) until 30 June 2017 Gina George (Retail and Catering Director) Paul Gray (Palaces Group Director) until 28 May 2018 Sue Hall (Finance Director) Richard Harrold OBE (Tower Group Director) Graham Josephs (Human Resources Director) Tom O’Leary (Public Engagement Director) from 6 September 2017 Adrian Phillips (Palaces and Collections Director) from 1 July 2017 Dan Wolfe (Communications and Development Director) Registered Office Hampton Court Palace Surrey KT8 9AU Auditors of the Group The Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 157-197 Buckingham Palace Road London SW1W 9SP Bankers Barclays Bank plc 1 Churchill Place Canary Wharf London E14 5HP Solicitors Farrer & Co 66 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3LH Historic Royal Palaces: Registered Charity number 1068852 Historic Royal Palaces Enterprises Ltd: Company limited by share capital, registered number 03418583 1 Trustees’ Report (continued) Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) was established in 1998 as a Royal Charter Body with charitable status. It is responsible for the care, conservation and presentation to the public of the unoccupied royal palaces: HM Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, Kensington Palace State Apartments, the Banqueting House at Whitehall and Kew Palace with the Royal Kitchens, Queen Charlotte’s Cottage and the Great Pagoda. -

Monoline Quill

MONOLINE Monoline pen is a high quality gel pen. It is the more affordable of the two options; however, we do not recommend it on shimmer paper or dark envelopes as it does not show true to color. It can also appear streaky on those paper finishes. Monoline ink cannot be mixed to match specific colors. I have attached a photo to show you what monoline pen would look like. As you can see from the photo, there is no variation in line weight. QUILL Quill is the traditional calligrapher's pen. It uses a metal nib that is dipped in an ink bottle before each stroke. It is the more luxurious of the options. On certain paper, you can feel the texture of the ink once it dries. Quill ink can also be mixed to match certain colors. As you can see from the photo, there is variation in line weight. Disclaimer: The majority of our pieces are individually handmade and handwritten (unless it is a printed mass production) therefore, the artwork in each piece will look different from each other. ORIGINAL Original has the standard amount of flourishes. CLEAN Clean has the least amount of flourishes. Disclaimer: The majority of our pieces are individually handmade and handwritten (unless it is a printed mass production) therefore, the artwork in each piece will look different from each other. FLOURISHED Extra flourishes are added. Fonts that can be flourished: **Royale, Eloise, Francisca, Luisa, and Theresa Classic UPRIGHT & ITALICIZED All fonts can be written upright or italicized. Disclaimer: The majority of our pieces are individually handmade and handwritten (unless it is a printed mass production) therefore, the artwork in each piece will look different from each other. -

Approaches to Greek History | University of Bristol

09/26/21 CLAS20039: Approaches to Greek History | University of Bristol CLAS20039: Approaches to Greek History View Online Alcock, Susan E., and Robin Osborne, Placing the Gods: Sanctuaries and Sacred Space in Ancient Greece (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994) Andersen, Helle Damgaard, Urbanization in the Mediterranean in the 9th to 6th Centuries BC (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press), vii Anderson, Greg, The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508-490 B.C. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003) Antonaccio, C.M., ‘Hybridity and the Cultures within Greek Culture’, in The Cultures within Ancient Greek Culture: Contact, Conflict, Collaboration (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 57–74 Antonaccio, M., ‘Ethnicity and Colonization’, in Ancient Perceptions of Greek Ethnicity (Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies, Trustees for Harvard University, 2001), v, 113–57 Austin, M. M., and Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Economic and Social History of Ancient Greece: An Introduction (London: B.T. Batsford, 1977) Balot, Ryan K., Greed and Injustice in Classical Athens (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press) Berent, Moshe, ‘Anthropology and the Classics: War, Violence, and the Stateless Polis’, The Classical Quarterly, 50.1 (1999), 257–89 <https://doi.org/10.1093/cq/50.1.257> Bergquist, Birgitta, and Svenska institutet i Athen, The Archaic Greek Temenos: A Study of Structure and Function (Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1967), xiii Blok, Josine, and A. P. M. H. Lardinois, Solon of Athens: New Historical and Philological Approaches (Leiden: Brill, 2006), cclxxii Boardman, John, The Greeks Overseas (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964) Boardman, John, and N. G. L. Hammond, The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol. -

Teacher Requisition Form

81075 Detach and photocopy—then give everyone their own form! Teacher Requisition Form Stop looking up individual items–our best-selling school supplies are all right here! Just fill in the quantity you want and total price! Here’s how to use this Teacher Requisition Form: 1. Distribute copies of this form to everyone making an order 2. For each item, fill in the quantity needed and the extended price 3. Attach completed Teacher Requisition Forms to your purchase order and account information, and return to Quill Important note: First column pricing 4. Attention School Office: We can hold your order for up to is shown on this form. 120 days and automatically release it and bill you on the day Depending on the total you specify. Just write Future Delivery on your purchase quantity ordered, your order, the week you want your order to ship, your receiving price may be even lower! hours and any special shipping instructions. Attach the Requisition Forms to your purchase order and account information Teacher Name:________________ School:__________________________ Account #: _________________ Email Address: Qty. Item Unit Total Qty. Item Unit Total Ord. Unit Number Description Price Price Ord. Unit Number Description Price Price ® PENCILS DZ 60139 uni-ball Vision, Fine, Red 18.99 DZ 60382 uni-ball® Vision, Fine, Purple 18.99 DZ T8122 Quill® Finest Quality Pencils, #2 1.89 DZ 60386 uni-ball® Vision, Fine, Green 18.99 DZ T812212 Quill® Finest Quality Pencils, #2.5 1.89 DZ 60387 uni-ball® Vision, Fine, Asst’d. Colors 18.99 DZ T8123 Quill® Finest Quality Pencils, #3 1.89 DZ 732158 Quill® Visible Ink Rollerball, Blue 9.99 DZ T7112 Quill® Standard-Grade Pencils, #2 1.09 DZ 732127 Quill® Visible Ink Rollerball, Black 9.99 DZ 13882 Ticonderoga® Pencils, #2 2.09 DZ 732185 Quill® Visible Ink Rollerball, Red 9.99 DZ 13885 Ticonderoga® Pencils, #2.5 2.09 DZ 84101 Flair Pens, Blue 13.99 DZ 13913 Ticonderoga® Pencils, #2, Black Fin. -

Making a Quill Pen This Activity May Need a Little Bit of Support However the End Project Will Be Great for Future Historic Events and Other Crafting Activities

Making A Quill Pen This activity may need a little bit of support however the end project will be great for future historic events and other crafting activities. Ask your maintenance person to get involved by providing the pliers and supporting with the production of the Quill Pen. What to do 1. Use needle-nose pliers to cut about 1" off of the pointed end of the turkey feather. 2. Use the pliers to pluck feathers from the quill as shown in the first photo on the next page. Leave about 6" of feathers at the top of the quill. 3. Sand the exposed quill with an emery board to remove flaky fibres and unwanted texture. Smoothing the quill will make it more pleasant to hold while writing. 4. If the clipped end of the quill is jagged and/or split, carefully even it out using nail scissors as shown in the middle photo. 5. Use standard scissors to make a slanted 1/2" cut on the tip of the quill as shown in the last photo below. You Will Need 10" –12" faux turkey feather Water -based ink 6. Use tweezers to clean out any debris left in the hollow of the quill. Needle -nose pliers 7. Cut a 1/2" vertical slit on the long side of the quill tip. When the Emery board pen is pressed down, the “prongs” should spread apart slightly as Nail scissors shown in the centre photo below. Tweezers Scissors Keeping it Easy Attach a ball point pen to the feather using electrical tape. -

Pen and Ink 3 Required Materials

Course: Pen and Ink 3 Required materials: 1. Basic drawing materials for preparatory drawing: • A few pencils (2H, H, B), eraser, pencil sharpener 2. Ink: • Winsor & Newton black Indian ink (with a spider man graphic on the package) This ink is shiny, truly black, and waterproof. Do not buy ‘calligraphy ink’. 3. Pen nibs & Pen holders : Pen nibs are extremely confusing to order online, and packages at stores have other nibs which are not used in class. Therefore, instructor will bring two of each nib and 1nib holders for each number, so students can buy them in the first class. Registrants need to inform the instructor if they wish to buy it in the class. • Hunt (Speedball) #512 Standard point dip pen and pen holder • Hunt (Speedball) # 102 Crow quill dip pen • Hunt (Speedball) # 107 Stiff Hawk Crow quill nib 4. Paper: • Strathmore Bristol Board, Plate, 140Lb (2-ply), (Make sure it is Plate surface- No vellum surface!) Pad seen this website is convenient: http://www.dickblick.com/products/strathmore-500-series-bristol-pads/ One or two sheets will be needed for each class. • Bienfang 360 Graphic Marker for preparatory drawing and tracing. Similar size with Bristol Board recommended http://www.dickblick.com/products/bienfang-graphics-360-marker-paper/ 5. Others: • Drawing board: Any board that can firmly hold drawing paper (A tip: two identical light weight foam boards serve perfectly as a drawing board, and keep paper safely in between while traveling.) * Specimen holder (frog pin holder, a small jar, etc.), a small water jar for washing pen nib) • Divider, ruler, a role of paper towel For questions, email Heeyoung at [email protected] or call 847-903-7348. -

The Influence of Writing Instruments on Handwriting and Signatures*

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 60 | Issue 1 Article 12 1969 The nflueI nce of Writing Instruments on Handwriting and Signatures Jacques Mathyer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Jacques Mathyer, The nflueI nce of Writing Instruments on Handwriting and Signatures, 60 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 102 (1969) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JouNAL or CImiNAL LAW, CRIUINOLOGY AND POLICE SCIENCE Vol. 60, No. 1 Copyright © 1969 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. THE INFLUENCE OF WRITING INSTRUMENTS ON HANDWRITING AND SIGNATURES* JACQUES MATHYER Professor Jacques Mathyer received the Diploma in Police Science (Criminalistics) in 1946 from the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and the Diploma in Criminology in 1957. During 1946-1947 he was assistant to Dr. Edmond Locard in Lyons, France, where he received his Doctor of Science Degree from the University of Lyons, 1947. After serving in the police laboratory of Vaud, Lausanne, Switzerland, he served from 1949 to 1963 as assistant to Professor Marc A. Bischoff at Institut de police scientifique et de criminologie of the University of Lausanne. Upon Professor Bischoff's re- tirement in 1963 he was named Professor and Director of the Institute. -

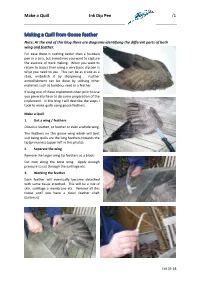

Making a Quill from Goose Feather Note: at the End of This Blog There Are Diagrams Identifying the Different Parts of Both Wing and Feather

Make a Quill Ink Dip Pen /1 Making a Quill from Goose feather Note: At the end of this blog there are diagrams identifying the different parts of both wing and feather. For ease there is nothing better than a fountain pen or a biro, but sometimes you want to capture the essence of mark making. When you want to return to basics then using a very basic dip pen is what you need to use. This can be as crude as a stick, embellish it by sharpening. Further embellishment can be done by utilising other materials such as bamboo, reed or a feather. If using one of these implements then prior to use you generally have to do some preparation of the implement. In this blog I will describe the steps I took to make quills using goose feathers. Make a Quill 1. Get a wing / feathers Obtain a feather, or feather or even a whole wing. The feathers on this goose wing which will best suit being quills are the long feathers towards the tip (primaries) (upper left in this photo). 2. Separate the wing Remove the larger wing tip feathers as a block. Cut own along the bone wing. Apply enough pressure to cut through the cartilage etc. 3. Working the feather Each feather will eventually become detached with some tissue attached. This will be a mix of skin, cartilage a membrane etc. Remove all this tissue until you have a clean feather shaft (calamus). Edt 03-18 Make a Quill Ink Dip Pen /2 4. Prepare the feather Then trim the feather barbs to leave at least half of the calamus clear.