NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION OLDFIELDS Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS by Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee

Field Notes - Spring 2016 Issue RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS By Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee We have been reviewing new books about the Olmsteds and the art of landscape architecture for so long that the book section of our website is beginning to resemble a bibliography. To make this resource more useful for researchers and interested readers, we’re beginning a series of articles about older publications that remain useful and enjoyable. We hope to focus on the landmarks of the Olmsted literature that appeared before the creation of our website as well as shorter writings that were not intended to be scholarly works or best sellers but that add to our understanding of Olmsted projects and themes. THE OLMSTEDS AND THE VANDERBILTS The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations 1879-1901. by John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson, Introduction by Louis Auchincloss. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991, 341 pages. At his death, William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) was the richest man in America. In the last eight years of his life, he had more than doubled the fortune he had inherited from his father, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), who had created an empire from shipping and then done the same thing with the New York Central Railroad. William Henry left the bulk of his estate to his two eldest sons, but each of his two other sons and four daughters received five million dollars in cash and another five million in trust. This money supported a Vanderbilt building boom that remains unrivaled, including palaces along Fifth Avenue in New York, aristocratic complexes in the surrounding countryside, and palatial “cottages” at the fashionable country resorts. -

Introducing Indiana-Past and Present

IndianaIntroducing PastPastPast ANDPresentPresent A book called a gazetteer was a main source of information about Indiana. Today, the Internet—including the Web site of the State of Indiana— provides a wealth of information. The Indiana Historian A Magazine Exploring Indiana History Physical features Physical features of the land Surficial have been a major factor in the growth and development of Indiana. topography The land of Indiana was affected by glacial ice at least three times Elevation key during the Pleistocene Epoch. The Illinoian glacial ice covered most of below 400 feet Indiana 220,000 years ago. The Wisconsinan glacial ice occurred 400-600 feet between 70,000 and 10,000 years ago. Most ice was gone from the area by 600-800 feet approximately 13,000 years ago, and 800-1000 feet the meltwater had begun the develop- ment of the Great Lakes. 1000-1200 feet The three maps at the top of these two pages provide three ways of above 1200 feet 2 presenting the physical makeup of the land. The chart at the bottom of page lowest point in Indiana, 320 feet 1 3 combines several types of studies to highest point in give an overview of the land and its 2 use and some of the unique and Indiana, 1257 feet unusual aspects of the state’s physical Source: Adapted from Indiana Geological Survey, Surficial To- features and resources. pography, <http:www.indiana. At the bottom of page 2 is a chart edu/~igs/maps/vtopo.html> of “normal” weather statistics. The first organized effort to collect daily weather data in Indiana began in Princeton, Gibson County in approxi- mately 1887. -

2017 Annual Report

INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY | 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 5836-18 - Annual Report 2017 - 20180406.indd 1 4/11/18 9:24 AM ii 5836-18 - Annual Report 2017 - 20180406.indd 2 4/11/18 9:24 AM LETTER from the PRESIDENT and CEO Dear friends and colleagues, I am so proud of everything we accomplished in 2017 – both at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center and in communities statewide. We reached 1.4 million people through visitation, programs, outreach and services. It was a great year, as you’ll see in this report. Everything we do is based on our mission as Indiana’s Storyteller and our commitment to collecting, preserving, interpreting and sharing our state’s history. We serve as an important resource for educators, students and researchers – professional and personal. We strive to make Indiana’s history relevant to the rest of the country’s history and to the world today. Connecting people to the past is our most important purpose, and we are able to do it in interesting ways thanks to your support and the support of our Board of Trustees and community advisors. Our particularly powerful You Are There about Italian POWs in Camp Atterbury has truly touched visitors to the History Center. You Are There: Eli Lilly at the Beginning brought thousands of people into Col. Lilly’s original lab. Our latest You Are There presents the Battle of Gettysburg in an innovative and captivating style. Our permanent Indiana Experience offerings of Destination Indiana, the W. Brooks and Wanda Y. Fortune History Lab and the Cole Porter Room continue to delight. -

Indiana ARIES 5 Crash Data Dictionary, 2011

State of Indiana (imp. 11/15/2011) Vehicle Crash Records System Data Dictionary Prepared by Appriss, Inc. - Public Information Management 5/15/2007 (Updated 11/30/2011) Indiana 2007 Page 1 of 148 VCRS Data Dictionary Header Information - Below is a desciption of each column of the data dictionary # Column Name Description 1. # Only used for the purposes of this data dictionary. Sequential number of the data element for each table. Numbering will restart for each table. 2. Table Name The name of the database table where the data element resides. If the data element does not exist in the database, the other location(s) of where the element resides will be noted (ie XML, Form Only). 3. XML Node The name of the XML node where the element resides. If the element does not exist in the XML file, the field will be left blank. 4. Database Column The name of the data element in the database and/or the XML file. Name/XML Field Name 5. Electronic Version The 'friendly' name of the data element on the electronic image of the crash report. If the report is printed or viewed on a Crash Report Form computer, this is the title for the appropriate data element. Name 6. Description Brief description of each data element. For more detailed information, refer to the ARIES User Manual. 7. Data Type Data element definition describing the value types allowed to be stored in the database. 8. Can be Null? Indicates whether null is allowed to be stored for this data element in the database. -

2020 Probabilistic Monitoring WP for the West Fork of the White River

2020 Probabilistic Monitoring Work Plan for the West Fork and Lower White River Basin Prepared by Paul D. McMurray, Jr. Probabilistic Monitoring Section Watershed Assessment and Planning Branch Indiana Department of Environmental Management Office of Water Quality 100 North Senate Avenue MC65-40-2 Shadeland Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2251 April 30, 2020 B-047-OWQ-WAP-PRB-20-W-R0 2020 Probabilistic Monitoring WP for the West Fork and Lower White River Basin B-047-OWQ-WAP-PRB-20-W-R0 April 30, 2020 This page is intended to be blank 2020 Probabilistic Monitoring WP for the West Fork and Lower White River Basin B-047-OWQ-WAP-PRB-20-W-R0 April 30, 2020 Approval Signatures _________________________________________________ Date___________ Stacey Sobat, Section Chief Probabilistic Monitoring Section _________________________________________________ Date___________ Cyndi Wagner, Section Chief Targeted Monitoring Section _________________________________________________ Date___________ Timothy Bowren, Project Quality Assurance Officer, Technical and Logistical Services Section _________________________________________________ Date___________ Kristen Arnold, Section Chief and Quality Assurance Manager Technical and Logistical Services Section, _________________________________________________ Date___________ Marylou Renshaw, Branch Chief and Branch Quality Assurance Coordinator IDEM Quality Assurance Staff reviewed and approves this Sampling and Analysis Work Plan. _________________________________________________ Date___________ Quality Assurance -

Indianapolis, IL – ACRL 2013

ArtsGuide INDIANAPOLIS ACRL 15th National Conference April 10 to April 13, 2013 Arts Section Association of College & Research Libraries WELCOME This selective guide to cultural attractions and events has been created for attendees of the 2013 ACRL Conference in Indianapolis. MAP OF SITES LISTED IN THIS GUIDE See what’s close to you or plot your course by car, foot, or public transit with the Google Map version of this guide: http://goo.gl/maps/fe1ck PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN INDIANAPOLIS Indianapolis and the surrounding areas are served by the IndyGo bus system. For bus schedules and trip planning assistance, see the IndyGo website: http://www.indygo.net. WHERE TO SEARCH FOR ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT NUVO is Indiana’s independent news organization: http://www.nuvo.net/ Around Indy is a community calendar: http://www.aroundindy.com/ THIS GUIDE HAS BEEN PREPARED BY Editor: Ngoc-Yen Tran, University of Oregon Contributors: | Architecture - Jenny Grasto, North Dakota State University | Dance - Jacalyn E. Bryan, Saint Leo University | Galleries - Jennifer L. Hehman, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis | Music - Anne Shelley, Illinois State University | Theatre - Megan Lotts, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey | Visual Arts & Museums - Alba Fernández-Keys, Indianapolis Museum of Art *Efforts were made to gather the most up-to-date information for performance dates, but please be sure to confirm by checking the venue web sites provided 1 CONTENTS ii-vi INTRODUCTION & TABLE OF CONTENTS ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN 5 Col. H. Weir Cook -

Scavenger Hunt!

ASHEVILLE URBAN TRAIL Scavenger Hunt! DISCOVER A SURPRISE ON EVERY CORNER! Welcome to the Asheville Urban Trail, a three-dimensional walk through time. Your visit will include a Scavenger Hunt with 30 official Urban Trail Stations and many other stops along the length of the walk. You can start and end anywhere, but Stations 16 through 30. Each half of we recommend completing the entire the trail will take from two to four hours, Asheville Urban Trail, even over multiple depending on your group size, the visits in order to fully appreciate the amount of time you spend interacting history and culture of our city. One with the history and activities laid out in practical approach is to walk the trail this workbook, and whether you choose in two parts: Stations 1 through 15 and to take detours. Name Date As you travel along the trail, stop Pay close attention and you’ll find the at each station, read the text and clues! Have fun and good luck! complete the activity. Each station has a bronze plaque which often contains The Urban Trail Markers are all clues or answers to the activities and engraved in pink granite -- and questions provided in this scavenger represent the way the trail is divided hunt. Walking directions will be marked into sections to further enrich the with an arrow symbol . stories of Asheville’s people, culture and history. Look for them and they will help you understand what’s going on in the city when these stories take place. Urban Trail Markers Feather The Gilded Age (1880 - 1930) Horseshoe The Frontier Period (1784 - 1880) Angel The Times of Thomas Wolfe (1900 - 1938) Courthouse The Era of Civic Pride Eagle The Age of Diversity 1 The Asheville Urban Trail Stations STATION 1: Walk Into History DETOUR: Grove Arcade 1a. -

Drive Historic Southern Indiana

HOOSIER HISTORY STATE PARKS GREEK REVIVAL ARCHITECTURE FINE RESTAURANTS NATURE TRAILS AMUSEMENT PARKS MUSEUMS CASINO GAMING CIVIL WAR SITES HISTORIC MANSIONS FESTIVALS TRADITIONS FISHING ZOOS MEMORABILIA LABYRINTHS AUTO RACING CANDLE-DIPPING RIVERS WWII SHIPS EARLY NATIVE AMERICAN SITES HYDROPLANE RACING GREENWAYS BEACHES WATER SKIING HISTORIC SETTLEMENTS CATHEDRALS PRESIDENTIAL HOMES BOTANICAL GARDENS MILITARY ARTIFACTS GERMAN HERITAGE BED & BREAKFAST PARKS & RECREATION AZALEA GARDENS WATER PARKS WINERIES CAMP SITES SCULPTURE CAFES THEATRES AMISH VILLAGES CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF COURSES BOATING CAVES & CAVERNS Drive Historic PIONEER VILLAGES COVERED WOODEN BRIDGES HISTORIC FORTS LOCAL EVENTS CANOEING SHOPPING RAILWAY RIDES & DINING HIKING TRAILS ASTRONAUT MEMORIAL WILDLIFE REFUGES HERB FARMS ONE-ROOM SCHOOLS SNOW SKIING LAKES MOUNTAIN BIKING SOAP-MAKING MILLS Southern WATERWHEELS ROMANESQUE MONASTERIES RESORTS HORSEBACK RIDING SWISS HERITAGE FULL-SERVICE SPAS VICTORIAN TOWNS SANTA CLAUS EAGLE WATCHING BENEDICTINE MONASTERIES PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S HOME WORLD-CLASS THEME PARKS UNDERGROUND RIVERS COTTON MILLS Indiana LOCK & DAM SITES SNOW BOARDING AQUARIUMS MAMMOTH SKELETONS SCENIC OVERLOOKS STEAMBOAT MUSEUM ART EXHIBITIONS CRAFT FAIRS & DEMONSTRATIONS NATIONAL FORESTS GEMSTONE MINING HERITAGE CENTERS GHOST TOURS LECTURE SERIES SWIMMING LUXURIOUS HOTELS CLIMB ROCK WALLS INDOOR KART RACING ART DECO BUILDINGS WATERFALLS ZIP LINE ADVENTURES BASKETBALL MUSEUM PICNICKING UNDERGROUND RAILROAD SITE WINE FESTIVALS Historic Southern Indiana (HSI), a heritage-based -

Foundation Document, George Rogers

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document George Rogers Clark National Historical Park Indiana July 2014 Foundation Document George Rogers Clark National Historical Park and Related Heritage Sites in Vincennes, Indiana S O I Lincoln Memorial Bridge N R I L L I E I V Chestnut Street R H A S Site of A B VINCENNES Buffalo Trace W UNIVERSITY Short Street Ford et GEORGE ROGERS CLARK e r t S Grouseland NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK t A 4 Home of William Henry Harrison N ot A levard c I Bou S Parke Stree t Francis Vigo Statue N D rtson I Culbe Elihu Stout Print Shop Indiana Territory Capitol 5 Vincennes State Memorial t e Historic Sites ue n Building North 1st Street re t e e v S et u n A Parking 3 Old French House tre s eh ve s S li A Cemetery m n po o e 2 Old State Bank cu Visitor Center s g e ri T e ana l State Historic Site i ar H Col Ind 7 t To t South 2nd Street e e Fort Knox II State Historic Site ee r Father Pierre Gibault Statue r treet t t North 3rd S 1 S and 8 Ouabache (Wabash) Trails Park Old Cathedral Complex Ma (turn left on Niblack, then right on Oliphant, t r Se Pe then left on Fort Knox Road) i B low S n B Bus un m il rr r Ha o N Du Barnett Street Church Street i Vigo S y t na W adway S s i in c tre er North St 4t boi h Street h r y o o S Street r n l e et s eet a t Stree Stre t e re s Stree r To 41 south Stre et reet To 6 t t reet t S et et Sugar Loaf Prehistoric t by St t t et o North 5th Stre Indian Mound Sc Shel (turn left on Washington Avenue, then right on Wabash Avenue) North 0 0.1 0.2 Kilometer -

Water Quality in the White River Basin—Indiana, 1992-96

science for a changing world Water Quality in the White River Basin Indiana, 1992–96 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1150 A COORDINATED EFFORT Coordination among agencies and organizations is an integral part of the NAWQA Program. We thank the following agencies and organizations who contributed data used in this report. • The Indiana Department of Natural Resources provided water-withdrawal data. • The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provided precipitation data. • The Indiana Agricultural Statistics Service provided pesticide-use data. • The Natural Resources Conservation Service provided soil-drainage data. • Many farmers and private landowners allowed us to drill and sample wells or tile drains on their properties. • The Indiana Department of Environmental Management provided ammonia and phosphorus data for the White River. • The Indiana State Department of Health, Indiana Department of Environmental Management, and Indiana Department of Natural Resources provided fish-consumption advisories. • The Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife, provided historical fish-community data. Additionally, the findings in this report would not have been possible without the efforts of the following U.S. Geological Survey employees. Nancy T. Baker Derek W. Dice Harry A. Hitchcock Jeffrey D. Martin Danny E. Renn E. Randall Bayless Nathan K. Eaton Glenn A. Hodgkins Rhett C. Moore Douglas J. Schnoebelen Jennifer S. Board Barton R. Faulkner David V. Jacques Sandra Y. Panshin Wesley W. Stone Donna S. Carter Jeffrey W. Frey C.G. Laird Patrick P. Pease Lee R. Watson Charles G. Crawford John D. Goebel Michael J. Lydy Jeffrey S. Pigati Douglas D. -

Jennings County Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2020-2024 JCPR MP

Jennings County Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2020-2024 JCPR MP JCPR Master Plan 2020-2024 Plan developed in coordination with the Jennings County Parks and Recreation Board Plan drafted by Greg Martin, Director JCPR JCPR Master Plan 2020-2024 2 JCPR MP 2020-2024 JCPR Master Plan 2020-2024 3 Table of Contents Section One: Introduction (page 5) Section Two: Goals and Objectives (page 11) Section Three: Features of Jennings County (page 15) Section Four: Supply Analysis (JCPR specific, page 53) (page 29) Section Five: Accessibility Analysis (page 73) Section Six: Public Participation (page 79) Section Seven: Issues Identification (page 79) Section Eight: Needs Analysis (page 97) Section Nine: New Facilities Location Map (page 125) Section Ten: Priorities and Action Schedule (page 143) Appendix: Miscellaneous (page 154) Double check all JCPR Master Plan 2020-2024 4 Section One: Introduction JCPR Master Plan 2020-2024 5 Park Board Members Department Contact Information Pat Dickerson President: Office location: 380 South County Road 90 West Muscatatuck Park North Vernon, IN 47265 (812) 346-7852 325 North State Highway # 3 (812) 569-7762 North Vernon, IN 47265 [email protected] Commissioner appointment (until 12-31-19) 812-346-2953 812-352-3032 (fax) Tom Moore [email protected] 2925 Deer Creek Road [email protected] North Vernon, IN 47265 (812) 346-1260 www.muscatatuckpark.com (812) 592-0319 [email protected] Judge appointment (until 12-31-21) Samantha Wilder Eco Lake Park Address: 495 Hayden Pike 9300 State Hwy # 7 North Vernon, IN 47265 Elizabethtown, In 47232 (812) 767-4150 [email protected] Judge appointment (until 12-31-21) Pat Hauersperger 565 N. -

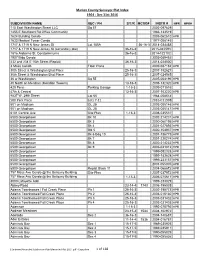

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave