Association Between Age, Gender and Multimorbidity Level and Receiving Home Health Care: a Population‑Based Swedish Study Andrzej Zielinski1* and Anders Halling2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. World Heritage Property Data 2. Statement of Outstanding Universal

Periodic Report - Second Cycle Section II-Naval Port of Karlskrona 1. World Heritage Property Data Comment Updated map with coodinate system included will be sent in 1.1 - Name of World Heritage Property by the Focal Point at Swedish National Heritage Board. Naval Port of Karlskrona Comment 1.5 - Governmental Institution Responsible for the Property The world heritage site of Karlskrona is planning for an application for name change. The application will be sent to Maria Wikman the Focal Point at Swedish National Heritage Board, but not Swedish National Heritage Board within the Periodic Reporting. Senior Adviser 1.2 - World Heritage Property Details 1.6 - Property Manager / Coordinator, Local Institution / Agency State(s) Party(ies) Anders Söderberg Sweden The County Administrative Board of Blekinge Type of Property Site Manager cultural Comment Identification Number The county Administrative Board of Blekinge has moved and 871 changed telephone numbers. New adress: The County Year of inscription on the World Heritage List Administrative Board of Blekinge Anders Söderberg Site Manager Skeppsbrokajen 4 SE-37186 Karlskrona Sweden 1998 Telephone: +46 10-22 40 000 Fax: +46 10-22 40 223 1.3 - Geographic Information Table 1.7 - Web Address of the Property (if existing) Name Coordinates Property Buffer Total Inscription 1. View photos from OUR PLACE the World Heritage (longitude / (ha) zone (ha) year latitude) (ha) collection Karlskrona and the 56.163 / 254.397 1105.077 1359.474 1998 2. Karlskrona kommun (only in Swedish) Island of Trossö , 15.583 3. Marinmuseum (The Naval Museum) Sweden 4. Karlskrona Live Mjölnarholmen , 56.167 / 15.6 6.825 ? 6.825 1998 Sweden 5. -

The Naval City of Karlskrona - an Active and Vibrant World Heritage Site –

The Naval City of Karlskrona - an active and vibrant World Heritage Site – “Karlskrona is an exceptionally well preserved example of a European naval base, and although its design has been influenced by similar undertakings it has in turn acted as a model for comparable installations. Naval bases played an important part during the centuries when the strength of a nation’s navy was a decisive factor in European power politics, and of those that remain from this period Karlskrona is the most complete and well preserved”. The World Heritage Sites Committee, 1998 Foreword Contents In 1972 UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, ratified 6-7 THIS IS A W ORLD HERITAGE SITE - the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and National Heritage with the HE AVAL ITY OF ARLSKRONA aim of protecting and preserving natural or cultural sites deemed to be of irreplaceable and T N C K universal value. The list of World Heritage Sites established under the terms of the Convention 8-13 THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND has been received with considerable interest by the international community and has greatly Why Karlskrona was established contributed to the strengthening of national cultural identity. Growth and expansion Models and ideals The Naval Town of Karlskrona was designated as a World Heritage Site in December 1998 and The af Chapman era is one of 12 such Sites that to date have been listed in Sweden. Karlskrona was considered of particular interest as the original layout of the town with its roots in the architectural ideals of 14–27 THE NAVAL BASE the baroque has been extremely well-preserved and for its remarkable dockyard and systems The naval dockyard and harbour of fortifications. -

Inskickat Nordic

http://www.diva-portal.org Preprint This is the submitted version of a paper published in REVUE D’HISTOIRE NORDIQUE. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Bergman, K. (2015) Qu’y avait-il de « moderne » dans les ports militaires de Suède aux XVIIe etXVIIIe siècle ? L’exemple de Karlskrona: What Was “Modern” about Naval Cities in 17th and 18th century Sweden?. REVUE D’HISTOIRE NORDIQUE, (18): 99-125 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:bth-765 Early modern naval cities, using the example of Karlskrona in Sweden: what was ‘modern’ in the early modern period? Abstract Could the early modern naval city be considered something special for its time, a city unlike other early modern cities? This article argues, using the example of Karlskrona in Sweden, that the European naval city in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries became what could be labelled a ‘hub’, where older ways of thinking and acting were confronted on a new level. The driving force behind this confrontation was Sweden’s ambition to become the major player in the Baltic Sea. With this military ambition followed new demands on existing methods of production and the handling of diseases. In order to reach its goals, Sweden had to build up a strong military state based on established trading networks in the Baltic area, and as these networks were in the hands of burghers, the state had to integrate them into its project by negotiation. -

Boatsmen in Blekinge

Boatsmen in Blekinge All pictures by Fredrik Franke These pages are about the boatsman in Blekinge, his family and his life. Since way, way back in time people and countries have been at war with each other. Finding soldiers willing to fight was not easy and the authorities solved the problems in different ways. They could for instance decide that for every 10th man in the village one had to be a soldier. Most of them were forced to against their will. The chance to come home from war was slight. During the reign of King Carl XI a new system was brought in in Sweden. The soldier was employed. He got a small dwelling, clothes and a salary that was paid by the farmers in the village. The group of farms employing one soldier was called a "rote" (division). The number of farms in a "rote" varied depending on how big the farms were. Blekinge became Swedish at the Peace of Roskilde in Denmark in 1658. Before that Blekinge was a Danish province. Quite soon after the Peace the Swedes built the towns of Karshamn and Karlskrona. Karlskrona became the naval head quarters for all of Sweden. Lots of people were needed to populate the new town, for the navy and the ship yard. To make it easier to find workers and seamen it was decided during the 1680´s that Blekinge and Södra Möre in the neighbouring county of Småland were to be divided into boatsmens companies. Since so many boatsmen were needed the system here got different to that of the rest of Sweden. -

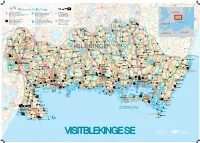

Visit Blekinge Karta

Påryd 126 Rävemåla 28 Törn Flaken Welcome to Blekinge 120 ARK56 Nav - Ledknutpunkt ARK56 Kajakled Blekingeleden Häradsbäck 120 Markerad vandringsled Sandsjön SWEDEN ARK56 Hub - Trail intersection120 Rekommenderad led för paddling Urshult Tingsryd Kvesen Vissefjärda ARK56 Knotenpunkt diverser Wege und Routen Recommended trail for kayaking Waymarked hiking trail ARK56 Węzeł - punkt zbiegu szlaków Empfohlener Paddel - Pfad Markierter Wanderweg 122 www.ark56.se Zalecana trasa kajakowa Oznakowany szlak pieszy Tiken 27 Dångebo Campingplatser - Camping Sydost RammsjönSkärgårdstrafik finns i området Sydostleden Arasjön Campsites - Camping Sydost Passenger boat services available Rekommenderad cykelled Stora Kinnen Halltorp Campingplatz - Camping Sydost Skärgårdstrafik - Passagierschiffsverkehr Recommended cycle trail Hensjön Ulvsmåla Älmtamåla Kemping - Camping Sydost Obszar publicznego transportu wodnego Empfohlener Radweg Baltic Sea www.campingsydost.se www.skargardstrafiken.com Zalecany szlak rowerowy 119 Ryd Djuramåla Saleboda DENMARKGullabo Buskahult Skumpamåla Spetsamåla Söderåkra Lyckebyån Siggamåla Åbyholm Farabol 119 Eringsboda Alvarsmåla Tjurkhult Göljahult Kolshult Falsehult POLAND130 126 GERMANY Mien Öljehult Husgöl Torsåsån Värmanshult Hjorthålan Holmsjö Fridafors R o Leryd Sillhöv- Kåraboda Björkebråten n Ledja n Boasjö 27 e dingen Torsås b y Skälmershult Björkefall å n Ärkilsmåla Dalanshult Hallabro Brännare- Belganet Hjortseryd Långsjöryd Klåvben St.Skälen Gnetteryd bygden Väghult Ebbamåla Alljungen Brunsmo Bruk St.Alljungen Mörrumsån -

In Karlskrona Puzzle Book! Who Are You?

ELI’S ADVENTUREs in karlskrona Puzzle book! Who are you? DRAW A SELF-PORTRAIT NAME: OR PLACE A PHOTO HERE AGE: ADDRESS: INTERESTS: FAVORITE FOOD: FAVORITE ANIMAL: FAVORITE PERSON: BEST ARTIST: WELCOME TO CONTENTS Karlskrona! Trossö 4 Wämö 7 Here you will find a lot to discover and explore. Eli will take you on an adventure journey through Stumholmen 8 the history of Karlskrona, where you get to visit interesting places and experience exciting ASPÖ 10 stories. Solve Eli’s tricky puzzles and learn more about how life was in the past from the tjurkö AND sturkö 11 old man Rosenbom. You will visit many unique places and buildings. The city is so unique that rödeby AND skärva 12 it has been appointed a World Heritage site. It means that some of the things you can see lyckeby 13 and visit only exist here – in the whole world! It is important that we help each other to take kristianopel 14 care of and protect the world’s natural and cultural heritages and our beautiful World THE KARLSKRONA- Heritage site. You can see which places that CROSSWORD PUZZLE 15 are part of Karlskrona’s World Heritage site by looking for this symbol in the puzzle book. answers 15 HELLO! MY NAME IS ELI. Production: Infab Kommunikation AB NICE TO MEET YOU! Project Manager: Elin Malmhult Graphic design and illustration: Karin Weandin Copywriter: Sarah Bruze THE FREDRIK Trossö CHURCH The Fredrik Church was opened in 1744 and got its name after King Fredrik I. It took 20 years to build the church and another 14 years before the two towers were completed! HERE’S SOME FISH! The Fisherman´s wife statue reminds us of all the women who stood at the Fish market to sell… Well, can you guess what? CAN YOU SOLVE THE RIDDLE? What are there three of in the Fredrik Church? ANSWER: DID YOU KNOW THAT… • Underneath Trossö there are secret military tunnels and rooms. -

Yngre Järnålder Till Medeltid I Blekinge Östra Härad

_____________________________________________________ Arkeologi 61-90hp _____________________________________________________ Yngre järnålder till medeltid i Blekinge Östra Härad En järnåldersbygd längs med en ådal i ett lokalt perspektiv Rickard Tovesson C-uppsats 15hp Handledare: Ulf Näsman Högskolan i Kalmar Humanvetenskapliga institutionen Höstterminen 2007 Examinator: Mats Larsson Abstract. Tovesson. R. 2007. Yngre järnålder i Blekinge Östra Härad. En järnåldersbygd längs med en ådal ett lokalt perspektiv. Late Iron Age in the eastern district of Blekinge. An Iron Age settlement area along a river valley in a local perspective. C-uppsats i arkeologi. Högskolan i Kalmar ht 2007. In this essay I have chosen to write about graves, settlements and historical, important central places during the late Iron Age and the introduction of Christianity in the east of Blekinge. The reason why I have chosen to write about this is because the area has many ancient monuments and not much have been written about the area. The main question is who where the people who lived there and why did they choose to settle there. Keywords. Settlements, graves, Iron Age, Blekinge, central places. Bild till omslaget: Rickard. Tovesson. INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING 1. INLEDNING 1 2. FRÅGESTÄLLNINGAR 1 3. MIN POSITION 1 4. METOD OCH TEORI 1 5. FORSKNINGSHISTORIK 2 6. FORSKNINGSOMRÅDE 3 6.1 Landskapets natur 3 6.2 Byar och Boplatser 3 7. JÄRNÅLDERNS BEBYGGELSE 4 8. GRAVAR 5 8.1 OM Järnålderns gravskick i Blekinge 5 8.2 Sagor och Mytologiska Teorier Om Gravseder 5 9. BÅTGRAVEN I AUGERUM 6 9.1 Övrigt om båtgravar 6 10. GRAVFÄLTEN VID AUGERUM 7 10.1 Gravfält 24:1 & 25:1 7 10.2 Gravfält 68:1 Vedeby kummel 8 10.2.1 Ovanliga skeppssättningar 8 10.3 Ekebacken. -

Naval Port of Karlskrona of Kristianopel and Ronneby, and the Region Was Progressively Assimilated Into Sweden

North Sea ports and broke Danish control over Öresund Sound, the key to Baltic trade. When peace with WORLD HERITAGE LIST Denmark was declared in 1658 with the Treaty of Roskilde, Skåne, Blekinge, and Gotland became Swedish Karlskrona (Sweden) territory. A garrison and shipyard were installed at the small port No 871 of Bodekull, renamed Karlshamn in honour of King Karl XI. However, after a short Danish occupation (1676-79), it was recognized that this was not the ideal site for a naval base, and so in 1680 Karl XI issued a charter for the foundation of a new town in the east of Blekinge on the islands of Wämö and Trossö, to be known as Karlskrona and to serve both as a port and as a naval base. Tradesmen and merchants from this hitherto Identification Danish area were forced into the new town by the withdrawal of their charters from the established towns Nomination The naval port of Karlskrona of Kristianopel and Ronneby, and the region was progressively assimilated into Sweden. Location Blekinge County The naval installations that developed at Karlskrona, beginning with a shipyard and storage facilities, were State Party Sweden initially supervised by Erik Dahlbergh, Quartermaster General, responsible for the defences of the Swedish Date 3 July 1997 kingdom. Naval architects and craftsmen were sent from Stockholm, and houses were built to receive them. The shipyard began with two building berths, two quays, two forges, and five warehouses; the first keel was laid down Justification by State Party in December 1680 and the first ship was launched the following year. -

Strategiska Noder Definitioner, Utpekade Platser Och Underlagsmaterial Version 2021-03-30 REGIONAL UTVECKLING

REGIONAL UTVECKLING Strategiska noder Definitioner, utpekade platser och underlagsmaterial Version 2021-03-30 REGIONAL UTVECKLING Innehållsförteckning Varför strategiska noder? ......................................................................................................... 3 Vilka är de strategiska noderna? ................................................................................................................. 3 Definition strategiska noder ...................................................................................................................... 4 Viljeinriktning strategiska noder ............................................................................................................... 4 Strategiska noder – kartor, underlagskartor och underlagsmaterial ...................................... 5 Karta 1: Platsernas befintliga strategiska egenskaper .......................................................................... 6 Karta 2: Strategiska noder med fullskaligt utbud ................................................................................... 7 Karta 3: Strategiska noder med icke fullskaligt utbud ........................................................................... 8 Karta 4: Strategiska noder – både med fullskaligt och icke fullskaligt utbud ................................... 9 Underlagskarta 1: Kommersiell och annan grundläggande service ..................................................... 10 Underlagskarta 2: Offentlig service ........................................................................................................ -

Reading Changing Planning Narratives

Making Plans – TELLING Making Plans – ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to understand how a ting societal structures, that stand in opposition repertoire of municipal planning narratives evol- to these structures, or that create a new identity Making Plans – TELLING STORIES: ved and how these were used as a means to ex- out of available resources. plain, legitimise and produce change in a city PLANNING IN KARLSKRONA/SWEDEN 1980 - 2010 that went through a process of urban transfor- Based on these readings, I find that the four do- mation. The focus is set on the role of narratives cuments use very different literary and rhetorical in municipal plans as a mental preparation for forms and that they construct the place’s identity change. In order to reach this aim, a framework in ways clearly distinct from each other. They for narrative analysis is developed that shall express various moral and political perspectives facilitate a critical reading of such municipal and convey clearly distinct social norms regar- planning documents as comprehensive plans. ding the role of inhabitants and the municipality. This shall help to understand among other things Over the decades, there has been a clear shift how place and community are constructed. This of expressed values from those that support a ST Mareile Walter framework is used to interpret four documents leading role of the (local) state in fostering lo- ORIES of the municipality of Karlskrona, one introduc- cal development to those that highlight the im- tory guide for new inhabitants from 1980, and portance of market actors and market forces. -

World Heritage Sites in Sweden WORLD HERITAGE SITES in SWEDEN

World Heritage sites in Sweden WORLD HERITAGE SITES IN SWEDEN Swedish National Heritage Board, Swedish National Commission for UNESCO Swedish Environmental Protection Agency Swedish National Heritage Board World Heritage Sites in Sweden – Swedish National Heritage Board 2014 Box 5405 Copyright for text and images, unless stated otherwise, in accordance with Creative Commons licence CC BY, recognition 2.5 Sweden SE-114 84 Stockholm http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/se/. Licence terms are currently Tel. +46 8-5191 8000 available online at: www.raa.se http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/se/legalcode. [email protected] If reworking the publication, logos and graphic elements must be removed from the reworked version. They are protected by law and are not covered by the Creative Commons licence above. Four front cover photos: Bengt A Lundberg/Raä: Sami Camp, Duolbuk / Tuolpuk, Laponia. Aspeberget, Tanum. Chinese Pavilion, Drottningholm. St. Nicolai ruins, Visby. Photo page 4: Archive photo. Back cover photo: © Folio. Maps © Lantmäteriet, reproduced with kind permission. Printing: Publit, print on demand. Printing: Taberg Media Group, offset. Graphic design: Jupiter Reklam. ISBN 978-91-7209-693-6 (PDF) ISBN 978-91-7209-694-3 (Print) FOREWORD 3 FOREWORD A World Heritage site is a site of special cultural or natu- We hope this book will meet the demand for informa- ral value that tells the story of the Earth and its people. tion and help increase public knowledge. Informing The Royal Domain of Drottningholm became the first the public about the World Heritage sites is also a of Sweden’s World Heritage sites in 1991, and most duty that Sweden took on when it signed the World recently the Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland Heritage Convention, the international agreement were included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in that forms the foundation of World Heritage work. -

Blekinge Archipelago

BIOSPHERE RESERVE NOMINATION FORM BLEKINGE ARCHIPELAGO Tärnö, Hällaryd archipelago in Karlshamn municipality Collaboration between Karlshamn, Karlskrona, and Ronneby municipalities and the Blekinge County Administrative Board The application documents are available on the website: www.blekingearkipelag.se Authors Blekinge County Administrative Board: Therese Asp, Anna-Karin Bilén, Jenny Hertz- man, Anette Johansson, Jonas Johansson, Elisabeth Lindberg, Ulf Lindahl, Lennart Olsson, Petra Torebrink, Elisabet Wallsten, Ulrika Olsson Widgren and Åke Widgren. Karlshamn Municipality: Lena Axelsson and Bernt Ibertsson. Karlskrona Municipality: Britt-Marie Havby, Birgith Juel and Sven-Olof Petersson. Ronneby Municipality: Emma Berntsson, Per Drysén, Anna-Karin Sonesson, and Yvonne Stranne. To assist with the nomination form the Biosphere Candidate Offi ce has sought special assistance from Björn Berglund, professor emeritus of quaternary geology, Lund Uni- versity and the fi rst conservation offi cer in Blekinge and Merit Kindström, research engineer at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Chapter 11 Physical Cha- racteristics) and Lars Emmelin, professor of environmental assessment, at Blekinge Institute of Technology (Chapter 15 Logistic Support Function). Several offi cials from the Nature and Environmental groups and the Fishing unit at the Blekinge County Administrative Board as well as offi cials from the municipalities have assisted with examining and commenting on the text. In addition, many people have contributed directly or indirectly with documentation and other material. Maps The Biosphere Candidate Offi ce has produced all the maps included in the nomination form and appendices. Background maps from National Land Survey of Sweden, serial no. 106-2004/188. Editorial Group for the Application Lena Axelsson, Anette Johansson, Elisabeth Lindberg, Sven-Olof Petersson, Anders Thurén, Elisabet Wallsten, and Ulrika Olsson Widgren.