Confiscation and Regrant: Matakana, Rangiwaea, Motiti and Tuhua: Raupatu and Related Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Port History to Modern Day August 2013

Port History to Modern Day S:\Port Information\Our Port History to Modern Day August 2013 2 EARLY HISTORY OF THE PORT OF TAURANGA 1290 Judge Wilson in his Sketches of Ancient Maori Life and History records that the canoe Takitumu carrying immigrants from Hawaiiki arrived in approximately 1290 AD and found Te Awanui (as Tauranga was then named) in the possession of a tribe of aborigines whose name, Puru Kopenga, or full net testified to the rich harvest to be drawn from the surrounding waters. 1769 In November, Captain James Cook passed close to Tauranga (pronounced Towrangha ) but did not enter the harbour. 1828 Probably the first European vessel to visit Tauranga was the missionary schooner Herald that called during this year. 1853 Captain Drury in HMS Pandora surveyed and charted the coast and harbour. 1864 Under the Marine Board Act of 1863, the Auckland Provincial Government Superintendent appointed the first pilot Captain T S Carmichael on 8 December 1864. He fixed leading buoys and marks in position to define the navigable channel, and his first piloting assignment was to bring HMS Esk into the harbour. The first house at Mount Maunganui was built for him late in 1866, to replace the tent in which he had lived during the previous two years. Copies of his early diaries are held in Tauranga s Sladden Library. Tauranga is probably the only Port in the country to experience a naval blockade. The Government of the day, fearful that arms would be run to hostile Maori warriors, imposed the blockade by notice in the New Zealand Gazette dated 2 April 1864. -

Matakana and Rangiwaea Islands Hapū Management

MATAKANA AND RANGIWAEA ISLANDS HAPŪ MANAGEMENT PLAN Edition 2 Updated March 2017 EDITION 2 - MATAKANA AND RANGIWAEA HMP UPDATED MARCH 2017 NGA HAPU O MATAKANA ME RANGIWAEA Tihei Mauriora Anei e whai ake nei nga korero e pa ana ki nga Moutere o Matakana me Rangiwaea hei whangai i te hinengaro. Kei konei nga whakaaro me nga tumanako a te hau kainga mo matou te iwi me o matou tikanga whakahaere i a matou ano, mo nga whenua me ona hua otira mo te taiao katoa e tau nei. Engari ko te mea nui kei roto ko a matou tirohanga whakamua me nga tumanako mo nga moutere nei. Nga mihi ki te hunga na ratou te mahi nui ki te tuitui i enei korero. Kia tau te mauri. EDITION 2 - MATAKANA AND RANGIWAEA HMP UPDATED MARCH 2017 NGA HAPU O MATAKANA ME RANGIWAEA Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................................. 6 PLANNING FRAMEWORK FOR MATAKANA AND RANGIWAEA ................................................. 7 PURPOSE OF THE HAPŪ MANAGEMENT PLAN ....................................................................... 10 PRINCIPLES OF CONSULTATION AND ENGAGEMENT WE WANT FOLLOWED ......................... 11 CONTACT DETAILS .................................................................................................................. 12 PROCESS FOR CONSULTATION AND ENGAGEMENT WITH OUR HAPŪ ................................... 13 ENVIRONMENT ...................................................................................................................... -

ROBERT a Mcclean R

ROBERT A McCLEAN R. A. McClean Matakana Island Sewerage Outfall Report VOLUMES ONE AND TWO: MAIN REPORT AND APPENDIX Wai 228/215 January 1998 Robert A McClean Any conclusions drawn or opinions expressed are those of the author. Waitangi Tribunal Research 2 R. A. McClean Matakana Island Sewerage Outfall Report THE AUTHOR My name is Robert McClean. I was born in Wellington and educated at Viard College, Porirua. After spending five years in the Plumbing industry, I attended Massey University between 1991 and 1996. I graduated with a Bachelor in Resource and Environmental Planning with first class honours and a MPhil in historical Geography with distinction. My thesis explored the cartographic history of the Porirua reserve lands. Between 1995 and 1997, I completed a report for the Porirua City Council concerning the the management. of Maori historical sites in the Porirua district. I began working for the Waitangi Tribunal in May 1997 as a research officer and I have produced a report concerning foreshores and reclamations within Te Whanganui-a Tara (Wellington Harbour, Wai 145). I am married to Kathrin and we have four children; Antonia, Mattea, Josef and Stefan. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to all those persons who have helped me research this claim. Especially Dr Johanna Rosier (Massey University), Andy Bruere, Rachel Dadson, Betty Martin (Environment B.O.P), Graeme Jelly, Alison McNabb (Western Bay of Plenty District Council), Bob Drey (MAF), David Phizacklea (DOC), Erica Rolleston (Secretary of Tauranga Moana District Maori Council), Christine Taiawa Kuka, Hauata Palmer (Matakana Island), Rachael Willan, Anita Miles and Morrie Love (Waitangi Tribunal). -

Matakana Island Wetland Restoration

Dune Restoration Trust of New Zealand National Conference, 2013 Nelson – A Region of Coastal Diversity Conference Presentation: Te Moutere o Matakana Restoration Projects The following presentation was given by Jason Murray & Aroha Armstrong. The Dunes Trust has been given permission by the presenters to make this document available from our website. However the information and images contained in the document belong to the presenters. To obtain permission to use the information and/or imagery used in this document for any other purpose please contact [email protected] The Dunes Trust would like to acknowledge WWF-New Zealand for sponsoring this presentation. www.dunestrust.org.nz Te Moutere o Matakana Restoration Projects 10th October 2011: Oil reaches the ocean beach of Matakana Island, a 27 km continuous stretch of coastline. Tangata whenua mobilise to start the oil clean up. Tangata whenua co -ordinate and mobilise whanau volunteer labour force from Matakana . The Debris hits on Jan 9th Greatest threat to our sensitive wildlife are the oil & debris - twine, polymer beads, wool , milk powder & food packets. Recovery Sifting the sand for the polymer beads and oil. Lamour Machine for oil Pipi The disruption of life cycles and habitats. Post-Rena Restoration Matakana Island Environment Group • Where have we come from? • What are we doing? • Who are we doing this for? • How have we achieved this? Understanding your environment • At least 40% of our diet comes from the moana • So why has it declined??? - wetlands/swamps etc used as rubbish tips - Unsustainable land-use e.g. agricultural farming - High nutrient load into the harbour - unsustainable land practices affect the water quality, degrade plant and animal habitats and upset life cycle balances that exist locally, regionally and nationally .What is the solution?? Matakana Is Nursery Matakana Island Nursery “Te Akakura” • The fresh water outlets and springs that are found throughout the island form part of the natural life cycle of the many fish and shellfish species found in the Tauranga Harbour. -

Huharua, Pukewhanake and Nga Kuri a Wharei

HUHARUA, PUKEWHANAKE, AND NGA KUru A WHAREI by Heather Bassett Richard Kay A research report commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal forWai 47 December 1996 238 J ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures 3 "11 Introduction 4 The Claim 4 :l 1. Buharua 6 '''-.- 1.1 Introduction 6 ~ 1.2 Raupatu and the Creation of Reserves 6 1.3 Alienation of Maori Reserves 12 1.4 Control, Management and Access to Huharua 17 J 1.5 Summary 20 2. Pukewhanake 22 J 2.1 Location and People ofPukewhanake 22 2.2 Raupatu West of the Wairoa River 23 2.3 Lot 178 Parish ofTe Puna 26 :1 2.4 Control, Use and Management ofPukewhanake 27 2.5 Summary 31 :J 3. Nga Kuri a Wharei 33 3.1 Traditional Boundary: 'Mai Tikirau ki Nga Kuri a Wharei' 33 :1 3.2 Raupatu Boundary 35 3.3 Summary 37 ] Bibliography 39 Appendix One: Statement of Claim, Wai 47 41 :J :J .J J "1 L ~ 1 ! u , ' ,- .. 2 239 TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1: Cultural Sites Around Tauranga Harbour (from Stokes, 1992, p 45) Figure 2: Fords from Plummers Point (from WI 35/161 Omokoroa - Te Puna, National Archives Wellington) Figure 3: Reserves in the Katikati Te Puna Purchase (from Stokes, 1990, p 192) Figure 4: Lot 210 Parish ofTe Puna (ML423A) Figure 5: Plummers Point 1886 (SO 5222) Figure 6: Lot 178 Parish ofTe Puna Today (SDIMap) Figure 7: Pa Sites on the Wairoa River 1864 (from Kahotea, 1996) Figure 8: Boundaries of the Katikati Te Puna Purchases (from Stokes, 1996) Figure 9: Plan of Native Reserves (ML 9760) Figure 10: Pukewhanake 1 October 1996 (Photos by author) Figure 11: Plan of the "Ngaiterangi" Purchase Deed (from Stokes, 1996) Figure 12: Plan of the Tawera Purchase Deed (from Stokes, 1996) Figure 13: Plan of the "Pirirakau" Purchase Deed (from Stokes, 1996) Figure 14: Boundaries of the Katikati Te Puna Purchases (from Stokes, 1996) Figure 15: Nga Kuri a Wharei and the Confiscation Line (from Stokes, Whanau a Tauwhao, p 19) 3 240 1. -

Sub-Surface Stratigraphy of Stella Passage, Tauranga Harbour

Sub-surface stratigraphy of Stella Passage, Tauranga Harbour 2013 ERI report number 28 Prepared for Port of Tauranga By Vicki Moon1, Willem de Lange1, Ehsan Jorat2, Amy Christophers1, Tobias Moerz2 Environmental Research Institute Faculty of Science and Engineering University of Waikato, Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240, New Zealand 1 Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Waikato, Private Bag 3150, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand 2 MARUM – Centre for Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Klagenfurter Strasse, 28359 Bremen, Germany Cite report as: Moon, V.G., de Lange, W.P., Jorat, M.E., Christophers, A. & Moerz, T., 2013. Sub-surface stratigraphy of Stella Passage, Tauranga Harbour. Environmental Research Institute Report No 28. Client report prepared for Port of Tauranga. Environmental Research Institute, Faculty of Science and Engineering, The University of Waikato, Hamilton. 23pp. Reviewed by: Approved for release by: Roger Briggs Professor David Lowe Honorary Fellow Chair, Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences University of Waikato University of Waikato Table of contents Table of contents 1 List of figures 2 List of tables 2 Introduction 3 Data sources 4 Borehole descriptions 4 Development of a 2D transect 6 Correlation of CPT, borehole, and seismic data 9 Development of a 3D model 12 Interpretation of model 14 Implications 16 Acknowledgements 17 References 17 Appendix 1 – Summarised core descriptions 18 Appendix 2 – GOST soundings 21 Appendix 3 – Seismic lines 22 1 List of tables Table 1. CPT and borehole descriptions used for this study. 6 List of figures Figure 1: Location map of Stella Passage, Tauranga Harbour, and summary of CPT and borehole locations used to derive the 2D model of sub-surface stratigraphy. -

Before the Auckland Unitary Plan Independent Hearings Panel

BEFORE THE AUCKLAND UNITARY PLAN INDEPENDENT HEARINGS PANEL IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Local Government (Auckland Transitional Provisions) Act 2010 AND IN THE MATTER of Topic 016 RUB North/West AND IN THE MATTER of the submissions and further submissions set out in the Parties and Issues Report JOINT STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF RYAN BRADLEY, DAVID HOOKWAY, AUSTIN FOX AND JOE JEFFRIES ON BEHALF OF AUCKLAND COUNCIL (PLANNING - RURAL AND COASTAL SETTLEMENTS NORTH) 15 OCTOBER 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 2 2. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 3. CODE OF CONDUCT .................................................................................................... 5 4. SCOPE .......................................................................................................................... 5 5. REZONING .................................................................................................................... 6 6. GROUPING OF SUBMISSIONS .................................................................................... 7 7. GROUP 1 - MATAKANA ................................................................................................ 7 8. GROUP 2 – WELLSFORD ........................................................................................... 13 9. GROUP 3 – TE HANA ................................................................................................ -

Funding Allocated YE2019

Funding Allocated YE2019 ORGANISATION PROJECT APPROVED COMMUNITY FACILITIES Bay of Plenty S port Climbing Assn Construction of a new Speed Wall $73,739 Good Neighbour Aotearoa Trust Kitchen Development $1 25,000 Greenpark S chool Playground $30,000 Homewood Park Tennis Club Inc. Court R esurfacing & Lighting Upgrade $25,21 5 Ngamuwahine Camp Trust new High R opes course $108,311 Otumoetai Intermediate S chool New S ports Turf $45,000 Pongakawa Playcentre Pergola $850 Tauranga Lawn Tennis Club Court R esurfacing & Lighting Upgrade $1 00,000 Tauranga Motorcycle Club Storage Shed $20,000 Tauranga RDA Foundation Building Extension & Covered Arena $200,000 Te K ura o Te Moutere o Matakana Outdoor Shade Canopy $50,000 Te Puke Cricket Club Pavillion Upgrade $50,000 Te Puke S mallbore R ifle Club R ange Upgrade $6,082 Te Puna Quarry Park Society Inc. Ampitheatre Seating Development $50,000 Welcome Bay Presbyterian Church Church Facilities Upgrade $7,000 K atch K atikati Arts J unction Project $30,000 Otumoetai Golf Club Storage Shed $1 0,000 Tauranga BMX Club Track Redevelopment $29,472 Bellevue Primary S chool S port & Performing Arts Centre $1 50,000 E nvirokatikati Charitable Trust Wetland Boardwalk Project $36,000 Harbourside Netball Court Resurfacing $1 00,000 Mount Maunganui Lifeguard Service New Clubhouse Building $300,000 Papamoa Community Surf Rescue Base Trust New Clubhouse Building $500,000 Papamoa S ports Tennis Club Building Alterations $1 0,500 Tauranga S quash Club Court Development $1 03,250 Te Ara K ahikatea Inc. Wetland Boardwalk Track Development $1 5,000 Te Puna Community Kindergarten New Kindergarten Building $52,967 Wesley Methodist Church Church Hall Upgrade $62,800 Bay of Plenty Paintball Club Site Development $1 5,000 K ids Campus Tauranga Community R oom Fitout $9,689 TOTAL $2,315,875 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Alzheimer’s S ociety Tauranga E ducation and support for people with Alzheimer's $45,000 Amputee Soc. -

Targa Rotorua 2021 Leg 1 Saturday 22Nd

H O G Waihi T G N Orokawa Bay D N A O aikino O Waihi Beach T R N K RA IG F TR SEAFORTH WA IHI RDFERGUS OL BEACH D FORD Island View TA UR A A Waimata R NG E A Bay of Plenty W R Athenree S D S E K D P U E P N N A ATHENREE C L E D Bowentown O T O Katikati N I W O Entrance 2 P S WOLSELEY R E N N HIKURANGI TA O W IR O P SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN O TU A D KAIMAI L A ONGARE POINT N AMAKU W D Tahawai I INT M LL K I PO SERVATION OU AUR a GH ta Karewa BY k PARK Woodlands a Island LIN n TargaDEMANN Rotorua 2021a ai Katikati D Is R la WHA EY n RAW RA L d HA ET RD T P TIR EA RD AR OH R SH AN W 2 Leg 1 G A A IR D Tauranga A R UI K S H A RING TA Harbour WAIHIRERE U P D S R A R M T D OPUHI RD D O N M H U K Aongatete A SaturdayL C 22ndMATAKANA PTMayT A A TR E K S N G AN N O ID A haftesbury SO T T P G D RD RE S Omokoroa Wairanaki M IN R O P O K F Bay TH OC L Pahoia L A Beach ru Mt Eliza HT T IG W E D A 581 D R Apata R N Mount Maunganui R W A Motiti Island O A O H K L R Tauranga A W O P K A U A E O G I Omokoroa ARK M I M Harbour O N W O Wairere R O K U A L C D Bay I I O Motunau Island O S L N D B O 2 Taumaihi (Plate Island) S R U N 2 A Otumoetai R S TAURANGA O P T D Island D MARANUI ST A K H A S Gordon R R R P G I E O R G Te N Kaimai Railway TunnelR A D L D I W U Tauranga D O A W Puna A O Bethlehem R M N Airport N D A e Y S M S U O P G M E I A R A N O R I Te Maunga P T R M O F 2 A E O A M DVILLE A F 29A O R A GOODWIN S W A A T DR B D S M Minden TOLL Kairua EA Papamoa Beach R D CH A OR Ngapeke S K F Waitao Y A W E U R A R N D E Whakamarama H D CR G IM Greerton -

The Archaeology of Matakana Island

1 THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL OF MATAKANA ISLAND REPORT PREPARED FOR WESTERN BAY OF PLENTY DISTRICT COUNCIL AND OTHERS BY KEN PHILLIPS (MA HONS) AUGUST 2011 ARCHAEOLOGY B.O.P. Heritage Consultants P O Box 855 Whakatane PHONE: 027 276 9919 EMAIL: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Project Background 3 Matakana Island 3 Resource Management Act 1991 3 New Zealand Historic Places Act 1993 4 Constraints and Limitations 4 METHODOLOGY 5 PHYSICAL LANDSCAPE 5 Geology 5 Soils 6 Vegetation 6 ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE 7 Previous Archaeological Research 7 Site Inventory 8 Archaeological Sites on the Barrier Dunes 10 Pa 10 Midden 10 Archaeological Sites on the Bulge and Rangiwaea Island 12 Pa 12 Undefended settlement and cultivation sites 14 Antiquity of Settlement of Matakana Island 16 Radiocarbon dates 16 Archaic settlement on Matakana Island13th – 15th Century 17 th th 16 – 19 Century 19 DISCUSSION 20 Archaeological Significance 20 The Bulge and Rangiwaea 20 The Barrier Dunes 20 Current Threats 21 RECOMMENDATIONS 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY 23 APPENDIX A: Topographic Map showing location and NZAA numbers of recorded archaeological sites on Matakana Island. 3 INTRODUCTION Project Background This archaeological report was commissioned by Western Bay of Plenty District Council in order to provide an overview of the archaeological resource on Matakana Island and forms part of the whole of island plan for Matakana Island in accordance with the Regional Policy Statement. The Regional Policy Statement states that Council shall: 17A.4(iv) Investigate a future land use and subdivision pattern for Matakana Island, including papakainga development, through a comprehensive whole of Island study which addresses amongst other matters cultural values, land which should be protected from development because of natural or cultural values and constraints, and areas which may be suitable for small scale rural settlement, lifestyle purposes or limited Urban Activities. -

Aide-Ntentoire "TE MANA"TO WHAKAHIA"TO OR.A •

MINISTRY OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Aide-ntentoire "TE MANA"TO WHAKAHIA"TO OR.A • . • !• : l ~ • Meeting Date: 20 October 2015 Security Level: IN CONFIDENCE For: Han Anne Tolley, Minister for Social Development CC: File Reference: . J Meeting with Minister Flavell Meeting details Expected , ' . attendees Purpose of meeting and TPK have been discussingno"i.•.t"we·ciin work to.gether to better support the achievement of Whanau Ora outcomes. TPK has identified options for managing the potential transfer of funding and/or programmes and has been discussing these with their Minister. • That the funding and/or programmes be transferred to TPK, who will then administer it via contract with the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agencies (TPK's recommended approach). • That the funding and/or programmes be administered by MSD via contract with the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agencies. • That MSD retains administration of the funding and/or programmes via contract with current providers, but incorporates a Whanau Ora approach. In terms of timing, TPK has advised Minister Flavell that the potential transfer could take place: • in a phased manner, upon the expiry of current contracts (TPK's recommended approach), or Bowen State Building, Bowen Street, PO Box 1556, Wellington -Telephone 04-916 3300 - Facsimile 04-918 0099 • as soon as possible, through contract novation and transfer. TPK has also raised with their Minister the possibility of a more immediate transfer of the currently uncommitted Te Punanga Haumaru (TPH) funding (approximately $2.55 million) to the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agencies. Key issues In Its advice, TPK has highlighted three key issues that it · recommends Minister Flavell raise with you In the meeting. -

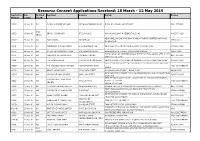

Resource Consent Applications Received: 18 March - 12 May 2019 Application Date Notified Applicant Location Details Planner Number Lodged Yes/No

Resource Consent Applications Received: 18 March - 12 May 2019 Application Date Notified Applicant Location Details Planner Number Lodged Yes/No 11369* 18-Mar-19 NO DONALD, ROBERT MICHAEL 367 MAUNGARANGI ROAD RURAL BOUNDARY ADJUSTMENT GAEL STEVENS FAST 11372* 19-Mar-19 SINGH, GURWINDER 5 FLEUR PLACE MINOR DWELLING IN RESIDENTIAL ZONE ROGER FOXLEY TRACK NEW DWELLING ENCROACHING ROAD BOUNDARY (WRITTEN APPROVAL 11368* 19-Mar-19 NO HART, MARIA 90 TIM ROAD CHRIS WATT OF ROADING) 11370* 19-Mar-19 NO WHITEMAN, RUSSELL KNIGHT 275 ATHENREE ROAD NEW SHED WITH FRONT YARD SETBACK IN RURAL ZONE ROGER FOXLEY 11373* 20-Mar-19 NO MCALISTER, LORRIMER CARLIE 614 KAITEMAKO ROAD DWELLING WITH A FRONT YARD ENCROACHMENT ANNA PRICE INSTALLATION OF SWIMMING POOL WITHIN AN ECOLOGICAL AREA (V14/2) 11376* 20-Mar-19 NO JAMIESON, CATHERINE ANN 733 MAKETU ROAD GAEL STEVENS AND A FLOOD ZONE 11380* 20-Mar-19 NO THE LODGE LIMITED 714 PYES PA ROAD (SH 36) NEW BUILDING TO PROVIDE FOR 104 BEDS FOR THE LODGE CARE HOME ROGER FOXLEY TO SELL LIQUOR ON SITE FOR THE ADDRESS INDIAN KITCHEN., HOURS OF 11389* 20-Mar-19 NO THE ADDRESS INDIAN KITCHEN 168 OMOKOROA ROAD OPERATION MONDAY TO SUNDAY 10AM TO 11PM JODY SCHUURMAN SHOP 3 11375* 21-Mar-19 NO BRAGG, HENRY EARLE 52 TAUPATA STREET BOUNDARY ADJUSTMENT - RURAL ZONE ANNA PRICE RETROSPECTIVE CONSENT FOR A 78.19M2 DWELLING AND AN ADDITIONAL 11374* 21-Mar-19 NO HEATON, SELWYN GEORGE 50 DILLON STREET ROGER FOXLEY DWELLING. CERT OF COMPLIANCE TO SELL LIQUOR ONSITE - HOURS OF OPERATION JP HOSPITALITY SOLUTIONS 11404* 25-Mar-19 NO MINDEN ROAD 9:30AM TO 10:30PM JODY SCHUURMAN LIMITED LINKED TO RC11203 11384* 25-Mar-19 NO OLD NEW ZEALAND LIMITED 665A MINDEN ROAD MINDEN 1A LIFESTYLE SUBDIVISION & MINDEN STABILITY AREA U.