Integrating Archaeology and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transactions and Transformations: Artefacts of the Wet Tropics, North Queensland Edited by Shelley Greer, Rosita Henry, Russell Mcgregor and Michael Wood

Transactions and Transformations: artefacts of the wet tropics, North Queensland Edited by Shelley Greer, Rosita Henry, Russell McGregor and Michael Wood MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM |CULTURE Volume 10 Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture 10 2016 | i Brisbane | December 2016 ISSN 2205-3220 Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 10 Transactions and Transformations: artefacts of the wet tropics, North Queensland Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editor: Geraldine Mate, PhD Issue Editors: Shelley Greer, Rosita Henry, Russell McGregor and Michael Wood PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2016 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 2205-3220 COVER Cover image: Rainforest Shield. Queensland Museum Collection QE246, collected from Cairns 1914. Traditional Owners, Yidinji People NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by: Fergies CONTENTS GREER, S., HENRY, R., MCGREGOR, R. -

Submission on Murrah Flora Reserves Draft Working Plan Thank You for This Opportunity to Comment on the State Forest Murrah Flora Reserves

31-Jan-18 Submission on Murrah Flora Reserves Draft Working Plan Thank you for this opportunity to comment on the State Forest Murrah Flora Reserves. We start by recognising OEH staff, Aboriginal and other conservationists whose evidence made saving our South Coast Koalas and ‘overarching values of the reserves’ overwhelmingly inevitable. NPWS managing one landscape under these two NSW Acts (Forestry & Parks) is not practical long-term. My management consultancy experience is from Industry, Government, National Parks Association (NSW) & Gulaga National Park Board (2007-2017). Projects include Unspoilt South Coast & Alps-to-Coast World Heritage. NSW Ministers said Murrah “PROTECTS SOUTH COAST KOALAS & LOCAL TIMBER INDUSTRY” (MR 1-Mar-16). Environment Minister Speakman told the ABC that flora reserves had the same protection as national parks. But local Liberal Andrew Constance, told media they kept the State Forest tenure “instead of national parks so in the future the operation of harvesting them again could be considered.” (Bega District News 4-Mar-16). Would Industry repay the $2.5M paid-out? How many of 278 jobs quoted depend on native forest sawlogs? We reference* opportunities within the 2017 Murrah Draft Plan, under three recommendations: 1. Add Murrah to existing Aboriginal-owned and NPWS co-managed Biamanga National Park [*P.1] ‘The primary purpose … is to conserve the south coast’s last known koala population and the protection of a natural and cultural landscape incorporating Biamanga and Gulaga national parks, both of which are Aboriginal owned and managed by a majority Aboriginal owner board’. [*P.3] ‘The boards aspire to … the Murrah Flora Reserves ultimately being added to Biamanga NP.’ We understand this NSW Government very nearly declared these Murrah Reserves as National Park! Mean-spirited State Forest tenure prevents Aboriginal Owners adding Murrah to their Biamanga NP Lease. -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Creating White Australia

Creating White Australia Edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Creating white Australia / edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky. ISBN: 9781920899424 (pbk.) Subjects: White Australia policy. Racism--Australia. Australia--Emigration and immigration--History. Australia--Race relations--History. Other Authors/Contributors: Carey, Jane, 1972- McLisky, Claire. Dewey Number: 305.80094 Cover design by Evan Shapiro, University Publishing Service, The University of Sydney Printed in Australia Contents Contributors ......................................................................................... v Introduction Creating White Australia: new perspectives on race, whiteness and history ............................................................................................ ix Jane Carey & Claire McLisky Part 1: Global -

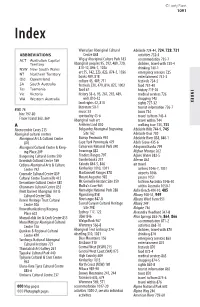

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Accessing Country Last Updated: May 2014

Aboriginal Communities Accessing Country Last updated: May 2014 These Fact Sheets are a guide only and are no substitute for legal advice. To request free initial legal advice on an environmental or planning law issue, please visit our website1 or call our Environmental Law Advice Line. Your request will be allocated to one of our solicitors who will call you back, usually within a few days of your call. Sydney: 02 9262 6989 Northern Rivers: 1800 626 239 Rest of NSW: 1800 626 239 EDO NSW has published a book on environmental Law for Aboriginal communities in NSW. For a more comprehensive guide, read Caring for Country: A guide to environmental law for Aboriginal communities in NSW. Overview Aboriginal people need to be able to access lands and waters to continue their traditions. These traditional practices include fishing, hunting, gathering food, camping, gathering firewood, visiting places with cultural significance, caring for country, caring for burial and other sites, and practising culture. Aboriginal people may always attempt to negotiate access, but the landowner may not always agree. The legal rights of Aboriginal people to access land and water depend on the legal status of the land or waterway. Further information about land dealings may be obtained from the EDO’s series of Fact Sheets and from the NSW Aboriginal Land Council. Access to particular types of land General A Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC) may negotiate an agreement with any land owner or occupier or person in control of land to permit an Aboriginal group or 1 http://www.edonsw.org.au/legal_advice 2 individual ‘to have access to the land for the purpose of hunting, fishing or gathering on the land’.2 If an agreement cannot be reached, the LALC may request that the Land and Environment Court issue a permit to access the land, or a right of way across the land, for the purpose of hunting, or fishing, or gathering traditional foods for domestic purposes.3 The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) allows for access agreements to be negotiated. -

Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 86 Friday, 2 October 2015

Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 86 Friday, 2 October 2015 The New South Wales Government Gazette is the permanent public record of official notices issued by the New South Wales Government. It also contains local council and other notices and private advertisements. The Gazette is compiled by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and published on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) under the authority of the NSW Government. The website contains a permanent archive of past Gazettes. To submit a notice for gazettal – see Gazette Information. 3045 NSW Government Gazette No 86 of 2 October 2015 Parliament PARLIAMENT ACTS OF PARLIAMENT ASSENTED TO Legislative Assembly Office, Sydney 28 September 2015 It is hereby notified, for general information, that His Excellency the Governor, has, in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty, this day assented to the under mentioned Acts passed by the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of New South Wales in Parliament assembled, viz.: Act No 25 — An Act with respect to providing incentives for economic development and job creation; to establish Jobs for NSW and the Jobs for NSW Fund; and for other purposes. [Jobs for NSW Bill] Act No 26 — An Act to constitute Dams Safety NSW and to confer functions on it relating to the safety of dams; and for related purposes. [Dams Safety Bill] Act No 27 — An Act to amend the Impounding Act 1993 to make further provision for the impounding of boat trailers left unattended for extended periods. [Impounding Amendment (Unattended Boat Trailers) Bill] Act No 28 — An Act to amend the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 in relation to the jurisdiction and powers of the Independent Commission Against Corruption. -

Perspective Statement

2015 Expert Meeting—Spatial Discovery Adler—1 PRUDENCE S. ADLER Associate Executive Director Association of Research Libraries Email: [email protected] Prudence S. Adler is the Associate Executive Director of the Association of Research Libraries. Her responsibilities include federal relations with a focus on information policy, intellectual property, public access policies including open access, accessibility for persons with disabilities and issues relating to access to government information. Prior to joining ARL in 1989, Adler was Assistant Project Director, Communications and Information Technologies Program, Congressional Office of Technology Assessment where she worked on studies relating to government information, networking and supercomputer issues, and information technologies and education. Adler has an M.S. in Library Science and M.A. in American History from the Catholic University of America and a B.A. in History from George Washington University. She has participated in several advisory councils including the Depository Library Council, the National Satellite Land Remote Sensing Data Archive Advisory Committee, the Board of Directors of the National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis, the National Research Council's Steering Committee on Geolibraries, the National Research Council Licensing Geographic Data and Services Committee, the National Institutes of Health PubMed Central National Advisory Committee, and the National Academy of Sciences Forum on Open Science. Perspective Statement he growing understanding of the value of open data in support of research, teaching and T learning presents an important opportunity for research institutions and their libraries. Be it funder policies such as the February 2013 OSTP memo on access to federally funded research resources or journal policies requiring the deposit of digital data associated with an article—for purposes of validation and reuse—in a trusted repository, some data require long-term preservation and access. -

NPWS Annual Report 2000-2001 (PDF

Annual report 2000-2001 NPWS mission NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3 Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview 8 Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Performance and future directions 45 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 46 Partners and stakeholders 8 Voluntary conservation agreements 46 Legal basis 8 Biodiversity conservation programs 46 Organisational structure 8 Wildlife management 47 Lands managed for conservation 8 Performance and future directions 48 Organisational chart 10 Ecologically sustainable management Key result areas 12 of NPWS operations 48 Threatened species conservation 48 1 Conservation assessment 13 Southern Regional Forest Agreement 49 NSW Biodiversity Strategy 14 Caring for the environment 49 Regional assessments 14 Waste management 49 Wilderness assessment 16 Performance and future directions 50 Assessment of vacant Crown land in north-east New South Wales 19 Managing our built assets 51 Vegetation surveys and mapping 19 Buildings 51 Wetland and river system survey and research 21 Roads and other access 51 Native fauna surveys and research 22 Other park infrastructure 52 Threat management research 26 Thredbo Coronial Inquiry 53 Cultural heritage research 28 Performance and future directions 54 Conservation research and assessment tools 29 Managing site use in protected areas 54 Performance and future directions 30 Performance and future directions 54 Contributing to communities 55 2 Conservation planning -

Accepted: April 15, 2013

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 5 MAY 2013 COMMENT ON DENHAM’S BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP PETER SUTTON UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE, AND SOUTH AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR SUBMITTED: APRIL 1, 2013 ACCEPTED: APRIL 15, 2013 MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ISSN 1544-5879 SUTTON: COMMENT ON DENHAM’S BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE WWW.MATHEMATICALANTHROPOLOGY.ORG MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 5 PAGE 1 OF 5 MAY 2013 COMMENT ON DENHAM’S BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP PETER SUTTON Denham begins his paper on Australian Aboriginal marriage with two diagrams, Figures 1.1 and 1.2, which he describes as ‘canonical mechanical models of Kariera and Aranda kinship’ (p. 4). These are what he calls examples of ‘generational closure’ because they, and so many other similar kinship term charts, indicate ‘systematic bilateral sibling exchange in marriage’ (p. 6 footnote 2). He then goes on to argue, persuasively, that for reasons of human biology, including the need to avoid inbreeding, and because of a significant average age gap between Aboriginal men and their wives under the classical regimes, such closure could not have been practicable. As a result, these societies were in fact more open than closed, as kin networks or groups, than orthodoxy would have us believe. In other words, men could not have, as a general rule, married their actual mothers’ brothers’ daughters as the kinship diagrams purported to describe. -

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic Studies of the Cranial Shape The

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic studies of the cranial shape The measurement of the human head of both the living and dead has long been a matter of interest to a variety of professions from artists to physicians and latterly to anthropologists (for a review see Spencer 1997c). The shape of the cranium, in particular, became an important factor in schemes of racial typology from the late 18th Century (Blumenbach 1795; Deniker 1898; Dixon 1923; Haddon 1925; Huxley 1870). Following the formulation of the cranial index by Retzius in 1843 (see also Sjovold 1997), the classification of humans by skull shape became a positive fashion. Of course such classifications were predicated on the assumption that cranial shape was an immutable racial trait. However, it had long been known that cranial shape could be altered quite substantially during growth, whether due to congenital defect or morbidity or through cultural practices such as cradling and artificial cranial deformation (for reviews see (Dingwall 1931; Lindsell 1995). Thus the use of cranial index of racial identity was suspect. Another nail in the coffin of the Cranial Index's use as a classificatory trait was presented in Coon (1955), where he suggested that head form was subject to long term climatic selection. In particular he thought that rounder, or more brachycephalic, heads were an adaptation to cold. Although it was plausible that the head, being a major source of heat loss in humans (Porter 1993), could be subject to climatic selection, the situation became somewhat clouded when Beilicki and Welon demonstrated in 1964 that the trend towards brachycepahlisation was continuous between the 12th and 20th centuries in East- Central Europe and thus could not have been due to climatic selection (Bielicki & Welon 1964). -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris ..................................