Molecular Systematics and Evolution of the Synallaxis Ruficapilla Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Atlantic Forest Hotspot: Brazil Briefing Book

Atlantic Forest Hotspot: Brazil Briefing Book Prepared for: Improving Linkages Between CEPF and World Bank Operations, Latin America Forum, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil—January 24 –25, 2005 ATLANTIC FOREST HOTSPOT: BRAZIL BRIEFING BOOK Table of Contents I. The Investment Plan • Ecosystem Profile Fact Sheet • Ecosystem Profile II. Implementation • Overview of CEPF’s Atlantic Forest Portfolio o Charts of Atlantic Forest o Map of Priority Areas for CEPF Grantmaking • Atlantic Forest Project Map • List of grants by Corridor III. Conservation Highlights • eNews and Press Releases from Atlantic Forest IV. Leveraging CEPF Investments • Table of Leveraged Funds • Documentation of Leveraged Funds CEPF FACT SHEET Atlantic Forest, Brazil Atlantic Forest Biodiversity Hotspot CEPF INVESTMENT PLANNED IN REGION Extreme environmental variations within the Atlantic Forest generate a $8 million diversity of landscapes with extraordinary biodiversity. The Atlantic Forest is one of the 25 richest and most threatened reservoirs of plant and animal life on Earth. These biodiversity hotspots cover only 1.4 percent of the planet yet QUICK FACTS contain 60 percent of terrestrial species diversity. What remains of the original Atlantic Forest occurs mostly in isolated remnants that are The Atlantic Forest is most famous for 25 different kinds of primates, 20 of scattered throughout landscapes dominated by agriculture. which are found only in this hotspot. The critically endangered northern muriquis and lion tamarins are among its best-known species. The Atlantic Forest contains an estimated 250 species of mammals, 340 amphibians, THREATS 1,023 birds and approximately 20,000 trees. The Atlantic Forest once stretched 1.4 million square kilometers but has been Half of the tree species are unique to this reduced to 7 percent of its original forest cover. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

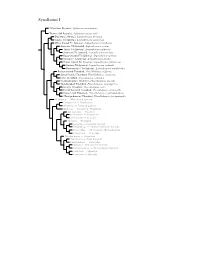

Synallaxini Species Tree

Synallaxini I ?Masafuera Rayadito, Aphrastura masafuerae Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Aphrastura spinicauda Des Murs’s Wiretail, Leptasthenura desmurii Tawny Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura yanacensis White-browed Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura xenothorax Araucaria Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura setaria Tufted Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura platensis Striolated Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striolata Rusty-crowned Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura pileata Streaked Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striata Brown-capped Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura fuliginiceps Andean Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura andicola Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura aegithaloides Rufous-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus rufifrons Streak-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticeps Little Thornbird, Phacellodomus sibilatrix Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Phacellodomus dorsalis Spot-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus maculipectus Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Freckle-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticollis Orange-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus ?Orange-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus ferrugineigula Hellmayrea — White-tailed Spinetail Coryphistera — Brushrunner Anumbius — Firewood-gatherer Asthenes — Canasteros, Thistletails Acrobatornis — Graveteiro Metopothrix — Plushcrown Xenerpestes — Graytails Siptornis — Prickletail Roraimia — Roraiman Barbtail Thripophaga — Speckled Spinetail, Softtails Limnoctites — ST Spinetail, SB Reedhaunter Cranioleuca — Spinetails Pseudasthenes — Canasteros Spartonoica — Wren-Spinetail Pseudoseisura — Cacholotes Mazaria – White-bellied -

Notes on the Distribution, Behaviour and First Description of the Nest Of

Cotinga 16 Notes on the distribution, behaviour and first description of the nest of Russet-bellied Spinetail Synallaxis zimmeri Irma Franke and Letty Salinas Cotinga 16 (2001): 90–93 El coliespina de pecho canela Synallaxis zimmeri es un ave endémica peruana conocida de tres localidades de la Cordillera Negra en el Perú central (09°27'S–09°53'S). Entre 1985 y 1988 fue encontrada en cuatro bosques nublados secos, ampliándose marcadamente el rango de distribución de la especie (07°42'S–10°03'S). En el bosque de Noqno (10°03'S 77°40'W, 2850 m), dpto. de Ancash, se encontró una población bastante numerosa de este coliespina y tres nidos, uno de ellos con pichones. El nido ocupado estaba ubicado a 4.2 m de altura entre ramas de Sebastiana obtusifolia y Myrcianthes quinqueloba. El nido es construido de ramitas espinosas entrelazadas y consta de tres partes. La primera es casi globular, de 26 cm de diámetro y contiene la cámara principal. La segunda parte es una extensión lateral de 20 cm de longitud y 8 cm de diámetro, formando el túnel de ingreso. La tercera, de 18 cm de diámetro, es una estructura globular construida de ramitas más gruesas entrelazadas con menor cuidado. La base de la cámara principal está acolchada con restos de hojas, principalmente nervaduras. Se realizaron observaciones del comportamiento de la hembra en las cercanías del nido durante un día. En el contenido de ocho estómagos se encontró que en promedio el 70 % del volumen consistía de insectos, de los cuales 28% eran insectos alados. -

CHESTNUT-THROATED SPINETAIL Synallaxis Cherriei K12

CHESTNUT-THROATED SPINETAIL Synallaxis cherriei K12 This little-known spinetail occurs in undergrowth in humid forest between 200 and 1,070 m at a handful of localities scattered across Brazil (six), Colombia (one), Ecuador (one) and Peru (four), and may be suffering from habitat loss. Whilst at one site it was only found in bamboo thickets inside at tall forest, which may partly explain its patchy distribution, competition from congeners also evidently plays a part. DISTRIBUTION The Chestnut-throated Spinetail occurs disjunctly in six areas of Brazil (nominate cherriei), with equally disjunct populations of the race napoensis (including the synonymized saturata of Carriker 1934) scattered through the foothills of the Andes in south-eastern Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. Given the breadth of this range, however, it is inevitable that many more localities will eventually be discovered. Brazil Localities for the species are as follows: Rondônia Barão de Melgaço, rio Ji-paraná, where the type-specimen was collected in March 1914 (Cherrie 1916, Gyldenstolpe 1930), this locality (previously part of Mato Grosso) being indicated as at 300 m (Paynter and Traylor 1991); Mato Grosso Alto Floresta, where a population was found in October 1989 (TAP); rio do Cágado, 250 m, 15°20’S 59°25’W, August 1987 and/or January 1988 (Willis and Oniki 1990, whence also coordinates); Pará 52 km south-south-west of Altamira on the east bank of the lower rio Xingu, 3°39’S 52°22’W, August/September 1986 (Graves and Zusi 1990, whence coordinates); in and adjacent to the Serra dos Carajás, namely at “Manganês” in the Serra Norte; and also at Gorotire, 7°40’S 51°15’W, near São Felix do Xingu, mid-1980s (Oren and da Silva 1987, whence coordinates). -

Avifauna of the Serra Das Lontras–Javi Montane Complex, Bahia, Brazil

Cotinga 24 Avifauna of the Serra das Lontras–Javi montane complex, Bahia, Brazil Luís Fábio Silveira, Pedro Ferreira Develey, José Fernando Pacheco and Bret M.Whitney Cotinga 24 (2005): 45–54 As regiões montanhosas costeiras do sul do estado da Bahia, Brasil, nunca foram objeto de maiores estudos ornitológicos até o início da década passada. A descoberta de uma comunidade única de aves nestas montanhas tem atraído a atenção de diversos pesquisadores, e novas espécies foram descritas ou redescobertas nestas serras litorâneas. Apesar de serem extremamente interessantes do ponto de vista biogeográfico, estas áreas são ainda muito pouco conhecidas e sofrem uma constante pressão antrópica. Dados sobre a avifauna das Serras das Lontras e do Javi foram obtidos em visitas esporádicas desde 1988, e uma visita mais longa foi realizada entre janeiro e fevereiro de 2001. Duas localidades em cada uma das serras foram amostradas e 295 espécies de aves foram registradas. Entre estas, dez espécies são enquadradas na categoria de ameaçadas, nove são vulneráveis e outras dez são consideradas como quase-ameaçadas. Nestas serras também ocorrem outras duas espécies ainda não descritas de Suboscines. A criação de Unidades de Conservação que possam proteger adequadamente esta importante e ainda razoavelmente bem preservada área de Floresta Atlântica é recomendada. The Atlantic Forest harbours a rich and diverse present study were to gather all available bird community of c.700 species, 200 of which are information concerning the avifauna of the Serra endemic to this biome and, of these, 140 are das Lontras–Javi complex, based on our own passerines7,21. In Brazil, the Atlantic Forest region research and data from colleagues, and to aid and its subtypes originally extended from the coast conservation strategies to be implemented by of Rio Grande do Norte south to northern Rio BirdLife International in collaboration with other Grande do Sul, in southernmost Brazil. -

An Overlooked Hotspot for Birds in the Atlantic Forest

ARTICLE An overlooked hotspot for birds in the Atlantic Forest Vagner Cavarzere¹; Ciro Albano²; Vinicius Rodrigues Tonetti³; José Fernando Pacheco⁴; Bret M. Whitney⁵ & Luís Fábio Silveira⁶ ¹ Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR). Santa Helena, PR, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0510-4557. E-mail: [email protected] ² Brazil Birding Experts. Fortaleza, CE, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] ³ Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Ecologia. Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2263-5608. E-mail: [email protected] ⁴ Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO). Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2399-7662. E-mail: [email protected] ⁵ Louisiana State University, Museum of Natural Science. Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Estados Unidos. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8442-9370. E-mail: [email protected] ⁶ Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Museu de Zoologia (MZUSP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2576-7657. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Montane and submontane forest patches in the state of Bahia, Brazil, are among the few large and preserved Atlantic Forests remnants. They are strongholds of an almost complete elevational gradient, which harbor both lowland and highland bird taxa. Despite being considered a biodiversity hotspot, few ornithologists have surveyed these forests, especially along elevational gradients. Here we compile bird records acquired from systematic surveys and random observations carried out since the 1980s in a 7,500 ha private protected area: Serra Bonita private reserve. We recorded 368 species, of which 143 are Atlantic Forest endemic taxa.