Lacan and Monotheism: Not Your Father's Atheism, Not Your

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monism and Monotheism in Al-Ghaz Lı's Mishk T Al-Anw R

Monism and Monotheism in al-Ghaz�lı’s Mishk�t al-anw�r Alexander Treiger YALE UNIVERSITY It is appropriate to begin a study on the problem of Monism versus Monotheism in Abü ˘�mid al-Ghaz�lı’s (d. 505/1111) thought by juxtaposing two passages from his famous treatise Mishk�t al-anw�r (‘The Niche of Lights’) which is devoted to an interpretation of the Light Verse (Q. 24:35) and of the Veils ˘adıth (to be discussed below).1 As I will try to show, the two passages represent monistic and monotheistic perspectives respectively. For the purposes of the present study, the term ‘monism’ refers to the theory, put forward by al-Ghaz�lı in a number of contexts, that God is the only existent in existence and the world, considered in itself, is ‘sheer non-existence’ (fiadam ma˛∂); while ‘monotheism’ refers to the view that God is the one of the totality of existents which is the source of existence for the rest of existents. The fundamental difference between the two views lies in their respective assessments of God’s granting existence to what is other than He: the monistic paradigm views the granting of existence as essentially virtual so that in the last analysis God alone exists, whereas the monotheistic paradigm sees the granting of existence as real.2 Let us now turn to the passages in question. Passage A: Mishk�t, Part 1, §§52–43 [§52] The entire world is permeated by external visual and internal intellectual lights … Lower [lights] emanate from one another the way light emanates from a lamp [sir�j, cf. -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

'ONE' in EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That We May Speak Of

MONO-, PAN-, AND COSMOTHEISM: THINKING THE 'ONE' IN EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That we may speak of Egyptian 'theology' is everything but self-evident. Theology is not something to be expected in every religion, not even in the Old Testament. In Germany and perhaps also elsewhere, there is a heated debate going on in OT studies about whether the subject of the discipline should be defined in the traditional way as "theology of OT" or rather, "history of Israelite religion".(1) The concern with questions of theology, some people argue, is typical only of Early Christianity when self-definitions and clear-cut concepts were needed in order to keep clear of Judaism, Gnosticism and all kinds of sects and heresies in between. Theology is a historical and rather exceptional phenomenon that must not be generalized and thoughtlessly projected onto other religions.(2) If theology is a contested notion even with respect to the OT, how much more so should this term be avoided with regard to ancient Egypt! The aim of my lecture is to show that this is not to be regarded as the last word about ancient Egyptian religion but that, on the contrary, we are perfectly justified in speaking of Egyptian theology. This seemingly paradoxical fact is due to one single exceptional person or event, namely to Akhanyati/Akhenaten and his religious revolution. Before I deal with this event, however, I would like to start with some general reflections about the concept of 'theology' and the historical conditions for the emergence and development of phenomena that might be subsumed under that term. -

Original Monotheism: a Signal of Transcendence Challenging

Liberty University Original Monotheism: A Signal of Transcendence Challenging Naturalism and New Ageism A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries by Daniel R. Cote Lynchburg, Virginia April 5, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Cote All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet Dr. T. Michael Christ Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity Dr. Phil Gifford Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Daniel R. Cote Liberty University School of Divinity, 2020 Mentor: Dr. T. Michael Christ Where once in America, belief in Christian theism was shared by a large majority of the population, over the last 70 years belief in Christian theism has significantly eroded. From 1948 to 2018, the percent of Americans identifying as Catholic or Christians dropped from 91 percent to 67 percent, with virtually all the drop coming from protestant denominations.1 Naturalism and new ageism increasingly provide alternative means for understanding existential reality without the moral imperatives and the belief in the divine associated with Christian theism. The ironic aspect of the shifting of worldviews underway in western culture is that it continues with little regard for strong evidence for the truth of Christian theism emerging from historical, cultural, and scientific research. One reality long overlooked in this regard is the research of Wilhelm Schmidt and others, which indicates that the earliest religion of humanity is monotheism. Original monotheism is a strong indicator of the existence of a transcendent God who revealed Himself as portrayed in Genesis 1-11, thus affirming the truth of essential elements of Christian theism and the falsity of naturalism and new ageism. -

PLUTARCH and “PAGAN MONOTHEISM” Frederick E. Brenk

PLUTARCH AND “PAGAN MONOTHEISM” Frederick E. Brenk When the Georgian poet, Rustaveli, visited Jerusa- lem in 1192, he recorded seeing on the frescoes of the Monastery of the Holy Cross, alongside Chris- tian saints, portraits of the Greek sages “such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cheilon, Thucydides, and Plutarch, just as they are to be found in our monastery on Athos”.1 One of the great religious and philosophical aspects of late antiquity was monotheism.2 In the second century the only really well-known monothe- istic religious groups were the Jews and Christians. Jews and Judaism were 1 S. Brock, “A Syriac Collection of Prophecies of the Pagan Philosophers”, in S. Brock, Studies in Syriac Christianity. History, Literature and Theology (Hampshire 1992) ch. VII (origi- nally OLP 14 [1983] 203–246 at 203). 2 See G. Fowden, Empire to Commonwealth. Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiq- uity (Princeton 1993); P. Athanassiadi & M. Frede (eds), Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity (Oxford 1999) and the review by M. Edwards, JThS 51 (2000) 339–342; R. Bloch, “Monotheism”, in Brill’s New Pauly, IX (2006) cols 171–174; C. Ando “Introduction to Part IV”, in idem (ed.), Roman Religion (Edinburgh 2003) 141–146; L.W. Hurtado, One God, One Lord. Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism (Philadelphia 2003); J. Assmann, “Monotheism and Polytheism”, in S. Iles Johnston (ed.), Religions of the Ancient World (Cambridge 2004) 17–31; M. Edwards, “Pagan and Christian Monotheism in the Age of Constantine”, in S. Swain & M. Edwards (eds), Approaching Late Antiquity. The Transformation from Early to Late Empire (Oxford 2004) 211–234; M. -

Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (History) Department of History 2015 Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present David B. Ruderman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers Part of the History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ruderman, D. B. (2015). Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present. Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies, 12 22-30. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/39 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/39 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present Abstract Monotheism, by simple definition, implies a belief in one God for all peoples, not for one particular nation. But as the Shemah prayer recalls, God spoke exclusively to Israel in insisting that God is one. This address came to define the essential nature of the Jewish faith, setting it apart from all other faiths both in the pre-modern and modern worlds. This essay explores the positions of a variety of thinkers on the question of the exclusive status of monotheism in Judaism from the Renaissance until the present day. It first discusses the challenge offered to Judaism by the Renaissance thinker Pico della Mirandola and his notion of ancient theology which claimed a common core of belief among all nations and cultures. -

Drawing from Mysticism in Monotheistic Religious Traditions to Inform Profound and Transformative Learning

112 Drawing from Mysticism in Monotheistic Religious Traditions To Inform Profound and Transformative Learning Michael Kroth1, Davin J. Carr-Chellman2, and Julia Mahfouz3 1University of Idaho--Boise, 2University of Dayton, and 3University of Colorado-Denver Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to introduce the processes and practices of mysticism found within the monotheistic traditions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, in an attempt to identify areas where these might inform, elaborate, and deepen our understanding of profound and transformative learning theory and practice. Keywords: monotheism, mysticism, profound learning, transformative learning theory “Mysticism has been called ‘the great spiritual current which goes through all religions.’” ~Annemarie Schimmel (2011, p. 4) The purpose of this paper is to introduce the processes and practices of mysticism within the monotheistic understandings of mysticism in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in an attempt to identify areas where these might inform, elaborate, and deepen our understanding of profound and transformative learning theory and practice. This article will briefly propose: 1) connections between mysticism, profound and transformative learning; and 2) examine the underpinnings of mysticism as both an experience and a process to inform transformational and profound learning theory. For this initial discussion, we have primarily drawn from some of the key texts and thinkers which have interpreted mysticism from the perspectives of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. By examining mysticism through three examples from monotheistic religions, this paper suggests that mysticism as an experience and process is strongly linked with profound and transformational learning and could be used to unpack ideas of transformative learning and also to help explicate the relationship of profound learning to transformative learning. -

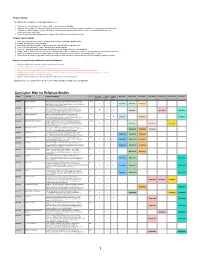

View the Curriculum

Program Mission The Mission of the Department of Religious Studies is to: 1. Introduce the methodologies of religious studies as an academic discipline 2. Advance the profession of religious studies through a commitment to scholarly research, publication, interpretation, and discussion 3. Cultivate an understanding of religious pluralism, including non-religious perspectives, in order to create global citizens in a religiously diverse world, and 4. Promote informed public dialogue about religion and its influence on society and culture. Program Learning Goals 1. Develop religious literacy in order for students to become responsible global citizens 2. Engage students in their own learning 3. Encourage students to analyze religion through the lenses of different world views 4. Connect theory and practice using examples from world religions 5. Challenge student presuppositions and ask students to reflect upon their inherited traditions 6. Analyze written, visual, or performed texts in religious studies with sensitivity to their diverse cultural contexts and historical moments 7. Argue from multiple perspectives about issues in religious studies that have both personal and global relevance 8. Demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of religious studies Degree Learning Outcomes/Student Learning Outcomes 1. Clarify the difference between religious studies and theology 2. Contextualize religious phenomena 3. Use logic and theoretical methods to analyze religious issues and solve problems 4. Argue from multiple perspectives about issues in religious studies that have personal and global relevance 5. Demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of religions 6. Communicate answers to real world problems 7. -

Copyrighted Material

1 Atheism, Agnosticism, and Theism Non - Religious Ethics is at a very early stage. We cannot yet predict whether, as in Mathematics, we will all reach agreement. Since we cannot know how Ethics will develop, it is not irrational to have high hopes. (Derek Parfi t, 1984) 1 He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God? (Micah 6:8) Let us start with what people most often associate with “ the secular outlook. ” If with anything at all, they associate it with atheism. But what is atheism? Sometimes atheism is presented as a coherent worldview, encompassing all the other traditions supposedly associated with the secular outlook. On this basis the Christian theologian and physicist Alister McGrath (1953 – ) writes: “ Atheism is the religion of the autonomous and rational human being, who believes that reason is able to uncover and express the deepest truths of the universe, from the mechanics of the rising sun to the nature and fi nal destiny of humanity. ” 2 The fi rst thing that strikes us is that atheism is presented here as a “ religion. ” A second point that is remarkable is that McGrath depicts as “ atheism ” beliefs that most people would associate with “ rationalism. ” In clarifying his defi nition the author even introduces other elements, such as optimism. Atheism, so McGrath writes, “ wasCOPYRIGHTED a powerful, self - confi dent, and aggressiveMATERIAL worldview. Possessed of a boundless confi dence, it proclaimed that the world could be fully 1 Parfi t , Derek , Reasons and Persons , Clarendon Press , Oxford 1984 , p. -

Atheism in the Ancient World

Also by Tim Whitmarsh Beyond the Second Sophistic: Adventures in Greek Postclassicism Narrative and Identity in the Ancient Greek Novel: Returning Romance The Second Sophistic Ancient Greek Literature Greek Literature and the Roman Empire: The Politics of Imitation THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF Copyright © 2015 by Timothy Whitmarsh All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., Toronto. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitmarsh, Tim. Battling the gods : the struggle against religion in ancient Greece / Tim Whitmarsh.—First Edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-307-95832-7 (hardcover)—ISBN 978-0-307-95833-4 (eBook) 1. Atheism—Greece—History. 2. Greece—Religion. 3. Christianity and atheism. I. Title. BL2747.3.W45 2015 200.938—dc23 2015005799 eBook ISBN 9780307958334 Cover image: Marble bust of Apollo. Regent Antiques, London, UK Cover design by Oliver Munday v4.1 ep Contents Cover Also by Tim Whitmarsh Title Page Copyright Dedication Preface A Dialogue Part One: Archaic Greece Chapter 1: Polytheistic Greece Chapter 2: Good Books Chapter 3: Battling the Gods Chapter 4: The Material Cosmos Part Two: Classical Athens Chapter 5: Cause and Effect Chapter 6: “Concerning the Gods, I Cannot Know” Chapter 7: