The Enigma of Terry Sawchuk in Randall Maggs's Night Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“To Tend Goal for the Greatest Junior Team Ever” – Ted Tucker, Former

“To tend goal for the greatest junior team ever” – Ted Tucker, former California Golden Seals and Montreal Junior Canadiens goalie by Nathaniel Oliver - published on August 30, 2016 Three of them won the Stanley Cup. One is in the Hockey Hall of Fame. Arguably three more should be. Six were NHL All-Star selections. Each one of them played professional hockey, whether it was in the NHL, WHA, or in the minors – they all made it to the pro level. And I am fortunate enough to have one of the two goaltenders for the 1968-69 Montreal Junior Canadiens – the team still widely considered the greatest junior hockey team of all time – to be sharing his story with me. Edward (Ted) William Tucker was born May 7th, 1949 in Fort William, Ontario. From his earliest moments of playing street hockey or shinny, Ted Tucker wanted to be a goaltender. Beginning to play organized hockey at the age of nine, there was minimal opportunity to start the game at a younger age. “At the time that I started playing hockey, there were no Tom Thumb, Mites, or Squirts programs in my hometown. There was a small ad in our local newspaper from the Elks organization, looking for players and asking which position you preferred to play. I asked my parents if I could sign up, and right from the get-go I wanted to be a goalie”. As a youngster, Tucker’s play between the pipes would take some time to develop, though improvement took place each year as he played. -

1965-66 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1965-66 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Toe Blake 2 Gump Worsley 3 Jacques Laperriere 4 Jean Guy Talbot 5 Ted Harris 6 Jean Beliveau 7 Dick Duff 8 Claude Provost 9 Red Berenson 10 John Ferguson 11 Punch Imlach 12 Terry Sawchuk 13 Bob Baun 14 Kent Douglas 15 Red Kelly 16 Jim Pappin 17 Dave Keon 18 Bob Pulford 19 George Armstrong 20 Orland Kurtenbach 21 Ed Giacomin 22 Harry Howell 23 Rod Seiling 24 Mike McMahon 25 Jean Ratelle 26 Doug Robinson 27 Vic Hadfield 28 Garry Peters 29 Don Marshall 30 Bill Hicke 31 Gerry Cheevers 32 Leo Boivin 33 Albert Langlois 34 Murray Oliver 35 Tom Williams 36 Ron Schock 37 Ed Westfall 38 Gary Dornhoefer 39 Bob Dillabough 40 Paul Popeil 41 Sid Abel 42 Roger Crozier Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Doug Barkley 44 Bill Gadsby 45 Bryan Watson 46 Bob McCord 47 Alex Delvecchio 48 Andy Bathgate 49 Norm Ullman 50 Ab McDonald 51 Paul Henderson 52 Pit Martin 53 Billy Harris 54 Billy Reay 55 Glenn Hall 56 Pierre Pilote 57 Al MacNeil 58 Camille Henry 59 Bobby Hull 60 Stan Mikita 61 Ken Wharram 62 Bill Hay 63 Fred Stanfield 64 Dennis Hull 65 Ken Hodge 66 Checklist 1-66 67 Charlie Hodge 68 Terry Harper 69 J.C Tremblay 70 Bobby Rousseau 71 Henri Richard 72 Dave Balon 73 Ralph Backstrom 74 Jim Roberts 75 Claude LaRose 76 Yvan Cournoyer (misspelled as Yvon on card) 77 Johnny Bower 78 Carl Brewer 79 Tim Horton 80 Marcel Pronovost 81 Frank Mahovlich 82 Ron Ellis 83 Larry Jeffrey 84 Pete Stemkowski 85 Eddie Joyal 86 Mike Walton 87 George Sullivan 88 Don Simmons 89 Jim Neilson (misspelled as Nielson on card) -

FALL 2015 GM's Notes Many Hands Make Light Work by Charles Musto

FALL Like us on Facebook: Follow us on Twitter Can You Volunteer? facebook.riverviewcc.ca @Riverview__CC email the GM at 2015 [email protected] THE RIVERVIEW REFLECTOR 90 Ashland Avenue Winnipeg MB R3L 1K6 Phone: 204-452-9944 [email protected] www.riverviewcc.ca Riverview Community Centre Fall/Winter Sports Registration starting soon! Rowdies Soccer (adults) Jackrabbits Hockey Jackrabbits Skiing Indoor Soccer Basketball Check our website www.riverviewcc.ca for more information. Inside This Issue THANK YOU VERE SCOtt 2 FIRst ANNUAL RIVERVIEW SLOW RIVERVIEW RAVENS SOftBALL 13 PRESIDENT'S NOTE 3 PITCH TOURNAMENT 9 GRANDS'N'MORE 14 UPCOMING EVENts 3 COMMUNITY CHALLENGE 9 GRACE BIBLE CHURCH 15 GM'S NOTES 4 KID'S CORNER 10&11 SOUTH OSBORNE LEGION 16 RVCC FEATURED IN FILM ABOUT HUGE SUCCEss FOR RIVERVIEW BIZZ BUZZ 17 TERRY SAWCHUK 7 GARAGE SALES 12 MINI SOCCER RECAP 18 SPRING CARNIVAL UPDATE 9 RIVERVIEW FUND BLITZ DELIVERS 12 SUMMER CAMP UPDATE 19 "September days are here, with summer’s best of weather, and autumn’s best of cheer." ~Helen Hunt Jackson WHO’S WHO @ RVCC THANK YOU VERE SCOTT President: Riverview Loses Ryan Rolston, ................204-889-0421, [email protected] a CommunityTreasure Vice-President: Dennis Cunningham, ....................................204-452-6229 y Treasurer: Krista Fraser-Kruck, n May 18, 2015, Vere Scott passed away. Vere was a re- t Secretary: Julie Strong searcher, ecologist, natural historian, local historian, teach- i O n General Manager: er and long time resident of Riverview. As a Riverview resident, u Charles Musto, .................................................204-452-9944 he was a regular contributor to the Riverview Reflector and Reflector Editing & Layout: he conducted extensive research on the history of River Park, m Trevor Johnson, ...............................................204-889-4482 which operated as an amusement park from 1891 till 1942. -

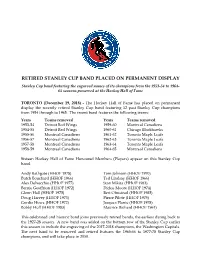

Retired Stanley Cup Band Placed on Permanent Display

RETIRED STANLEY CUP BAND PLACED ON PERMANENT DISPLAY Stanley Cup band featuring the engraved names of its champions from the 1953-54 to 1964- 65 seasons preserved at the Hockey Hall of Fame TORONTO (December 19, 2018) - The Hockey Hall of Fame has placed on permanent display the recently retired Stanley Cup band featuring 12 past Stanley Cup champions from 1954 through to 1965. The recent band features the following teams: Years Teams removed Years Teams removed 1953-54 Detroit Red Wings 1959-60 Montreal Canadiens 1954-55 Detroit Red Wings 1960-61 Chicago Blackhawks 1955-56 Montreal Canadiens 1961-62 Toronto Maple Leafs 1956-57 Montreal Canadiens 1962-63 Toronto Maple Leafs 1957-58 Montreal Canadiens 1963-64 Toronto Maple Leafs 1958-59 Montreal Canadiens 1964-65 Montreal Canadiens Sixteen Hockey Hall of Fame Honoured Members (Players) appear on this Stanley Cup band. Andy Bathgate (HHOF 1978) Tom Johnson (HHOF 1970) Butch Bouchard (HHOF 1966) Ted Lindsay (HHOF 1966) Alex Delvecchio (HHOF 1977) Stan Mikita (HHOF 1983) Bernie Geoffrion (HHOF 1972) Dickie Moore (HHOF 1974) Glenn Hall (HHOF 1975) Bert Olmstead (HHOF 1985) Doug Harvey (HHOF 1973) Pierre Pilote (HHOF 1975) Gordie Howe (HHOF 1972) Jacques Plante (HHOF 1978) Bobby Hull (HHOF 1983) Maurice Richard (HHOF 1961) This celebrated and historic band joins previously retired bands, the earliest dating back to the 1927-28 season. A new band was added on the bottom row of the Stanley Cup earlier this season to include the engraving of the 2017-2018 champions, the Washington Capitals. The next band to be removed and retired features the 1965-66 to 1977-78 Stanley Cup champions, and will take place in 2030. -

For the Record

FOR THE RECORD MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT HUGH VASSOS We are entering a new era in the life of the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame. We need to make improvements in virtually all areas of our operations while focusing on our core business…the preservation and education of this province’s rich and proud sports history. Now is the time for everyone with a vested interest in the Hall of Fame to step forward and do their part to make this a better place. Our Board of Directors and Staff are leading the way. Over the past few months we have reviewed the way we are currently operating and developed a plan for the way we need and want to work from this point forward. On April 16th we announced the first of these plans including a new visual identity that replaces a dated logo with a more dynamic image that better reflects our new attitude and sense of direction for the future. A new online presence and domain name (www.sasksportshalloffame.com) that adopts a more contemporary look and meshes with our social media applications (@SaskSportsHF and www.facebook.com/SaskSportsHF). In order to put our new Strategic Plan into motion it will take resources and that’s where you come in. We have made the decision to create our own destiny and have launched an exciting new self-help program entitled the Sports Investors Club. This program is poised to generate up to 50% of our operating revenue while allowing us to also start funding new exhibits and programs. -

Vol.37 No.6 D'océanographie

ISSN 1195-8898 . CMOS Canadian Meteorological BULLETIN and Oceanographic Society SCMO La Société canadienne de météorologie et December / décembre 2009 Vol.37 No.6 d'océanographie Le réseau des stations automatiques pour les Olympiques ....from the President’s Desk Volume 37 No.6 December 2009 — décembre 2009 Friends and colleagues: Inside / En Bref In late October I presented the CMOS from the President’s desk Brief to the House of Allocution du président Commons Standing by/par Bill Crawford page 177 Committee on Finance at its public hearing in Cover page description Winnipeg. (The full text Description de la page couverture page 178 of this brief was published in our Highlights of Recent CMOS Meetings page 179 October Bulletin). Ron Correspondence / Correspondance page 179 Stewart accompanied me in this presentation. Articles He is a past president of CMOS and Head of the The Notoriously Unpredictable Monsoon Department of by Madhav Khandekar page 181 Environment and Geography at the The Future Role of the TV Weather Bill Crawford Presenter by Claire Martin page 182 CMOS President University of Manitoba. In the five minutes for Président de la SCMO Ocean Acidification by James Christian page 183 our talk we presented three requests for the federal government to consider in its The Interacting Scale of Ocean Dynamics next budget: Les échelles d’interaction de la dynamique océanique by/par D. Gilbert & P. Cummins page 185 1) Introduce measures to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions; Interview with Wendy Watson-Wright 2) Invest funds in the provision of science-based climate by Gordon McBean page 187 information; 3) Renew financial support for research into meteorology, On the future of operational forecasting oceanography, climate and ice science, especially in tools by Pierre Dubreuil page 189 Canada’s North, through independent, peer-reviewed projects managed by agencies such as CFCAS and Weather Services for the 2010 Winter NSERC. -

An Educational Experience

INTRODUCTION An Educational Experience In many countries, hockey is just a game, but to Canadians it’s a thread woven into the very fabric of our society. The Hockey Hall of Fame is a museum where participants and builders of the sport are honoured and the history of hockey is preserved. Through the Education Program, students can share in the glory of great moments on the ice that are now part of our Canadian culture. The Hockey Hall of Fame has used components of the sport to support educational core curriculum. The goal of this program is to provide an arena in which students can utilize critical thinking skills and experience hands-on interactive opportunities that will assure a successful and worthwhile field trip to the Hockey Hall of Fame. The contents of this the Education Program are recommended for Grades 6-9. Introduction Contents Curriculum Overview ……………………………………………………….… 2 Questions and Answers .............................................................................. 3 Teacher’s complimentary Voucher ............................................................ 5 Working Committee Members ................................................................... 5 Teacher’s Fieldtrip Checklist ..................................................................... 6 Map............................................................................................................... 6 Evaluation Form……………………............................................................. 7 Pre-visit Activity ....................................................................................... -

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

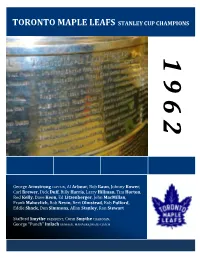

TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 6 2 George Armstrong CAPTAIN, Al Arbour, Bob Baun, Johnny Bower, Carl Brewer, Dick Duff, Billy Harris, Larry Hillman, Tim Horton, Red Kelly, Dave Keon, Ed Litzenberger, John MacMillan, Frank Mahovlich, Bob Nevin, Bert Olmstead, Bob Pulford, Eddie Shack, Don Simmons, Allan Stanley, Ron Stewart Stafford Smythe PRESIDENT, Conn Smythe CHAIRMAN, George “Punch” Imlach GENERAL MANAGER/HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1962 STANLEY CUP SEMI-FINAL 1 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 98 v. 3 CHICAGO BLACK HAWKS 75 GM FRANK J. SELKE, HC HECTOR ‘TOE’ BLAKE v. GM TOMMY IVAN, HC RUDY PILOUS BLACK HAWKS WIN SERIES IN 6 Tuesday, March 27 Thursday, March 29 CHICAGO 1 @ MONTREAL 2 CHICAGO 3 @ MONTREAL 4 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD NO SCORING 1. CHICAGO, Bobby Hull 1 (Bill Hay, Stan Mikita) 5:26 PPG 2. MONTREAL, Dickie Moore 2 (Bill Hicke, Ralph Backstrom) 15:10 PPG Penalties – Moore M 0:36, Horvath C 3:30, Wharram C Fontinato M (double minor) 6:04, Fontinato M 11:00, Béliveau M 14:56, Nesterenko C 17:15 Penalties – Evans C 1:06, Backstrom M 3:35, Moore M 8:26, Plante M (served by Berenson) 9:21, Wharram C 14:05, Fontinato M 17:37 SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING SECOND PERIOD 3. -

1969-70 Topps Hockey Card Checklist+A1

1 969-70 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD CHECKLIST+A1 1 Gump Worsley 2 Ted Harris 3 Jacques Laperriere 4 Serge Savard 5 J.C. Tremblay 6 Yvan Cournoyer 7 John Ferguson 8 Jacques Lemaire 9 Bobby Rousseau 10 Jean Beliveau 11 Henri Richard 12 Glenn Hall 13 Bob Plager 14 Jim Roberts 15 Jean-Guy Talbot 16 Andre Boudrias 17 Camille Henry 18 Ab McDonald 19 Gary Sabourin 20 Red Berenson 21 Phil Goyette 22 Gerry Cheevers 23 Ted Green 24 Bobby Orr 25 Dallas Smith 26 Johnny Bucyk 27 Ken Hodge 28 John McKenzie 29 Ed Westfall 30 Phil Esposito 31 Derek Sanderson 32 Fred Stanfield 33 Ed Giacomin 34 Arnie Brown 35 Jim Neilson 36 Rod Seiling 37 Rod Gilbert 38 Vic Hadfield 39 Don Marshall 40 Bob Nevin 41 Ron Stewart 42 Jean Ratelle Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Walter Tkaczuk 44 Bruce Gamble 45 Tim Horton 46 Ron Ellis 47 Paul Henderson 48 Brit Selby 49 Floyd Smith 50 Mike Walton 51 Dave Keon 52 Murray Oliver 53 Bob Pulford 54 Norm Ullman 55 Roger Crozier 56 Roy Edwards 57 Bob Baun 58 Gary Bergman 59 Carl Brewer 60 Wayne Connelly 61 Gordie Howe 62 Frank Mahovlich 63 Bruce MacGregor 64 Alex Delvecchio 65 Pete Stemkowski 66 Denis DeJordy 67 Doug Jarrett 68 Gilles Marotte 69 Pat Stapleton 70 Bobby Hull 71 Dennis Hull 72 Doug Mohns 73 Jim Pappin 74 Ken Wharram 75 Pit Martin 76 Stan Mikita 77 Charlie Hodge 78 Gary Smith 79 Harry Howell 80 Bert Marshall 81 Doug Roberts 82 Carol Vadnais 83 Gerry Ehman 84 Bill Hicke 85 Gary Jarrett 86 Ted Hampson 87 Earl Ingarfield 88 Doug Favell 89 Bernie Parent Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 90 Larry Hillman -

Western Canada Wasn't Kind to Scotty Bowman

Memories of Sport By Kent Morgan (courtesy of Canstar Community News) Western Canada wasn't kind to Scotty Bowman When Scotty Bowman was beginning his Hall of Fame coaching career, Western Canada was not welcoming. In 1957 Bowman came west with the Ottawa Canadiens as general manager and coach Sam Pollock's assistant. The powerful Montreal Canadiens sponsored team was highly favoured to beat the upstart Flin Flon Bombers in the Canadian junior final, but Bombers prevailed in a series that went seven games. The next season when the Memorial Cup final was played in the east, the pair were in charge of the renamed Ottawa-Hull Canadiens. After knocking off Toronto Marlboros in the eastern final, Ottawa-Hull met another Montreal farm squad, the Regina Pats, and won the Canadian junior championship in six games. In 1959, the 25-year-old Bowman was in charge of a different Habs farm squad, the Peterborough TPT Petes. The Ontario champions - with future NHLers Wayne Connelly, Jimmy Roberts, Barclay Plager and Denis DeJordy - in the lineup beat Pollock's Ottawa- Hull squad in the Eastern final. Bowman had to bring his team west to Winnipeg where a somewhat-surprising opponent was waiting for them. The Winnipeg Braves had won the MJHL championship over another Montreal- sponsored squad, the St. Boniface Canadiens, and reached the Western final by beating the Fort William Canadiens. Flin Flon led by River Heights product Cliff Pennington, the SJHL scoring champion and most valuable player, was heavily favoured in the final. The Bombers won the first two games in Flin Flon, 5-1 and 7-4. -

Gordie Howe Was a Symbol of NHL Past

This page was exported from - The Auroran Export date: Sat Oct 2 9:10:59 2021 / +0000 GMT FIVE MINUTE MAJOR: Gordie Howe was a symbol of NHL past By Jake Courtepatte As a twenty-something, I find it surprisingly difficult to write how I feel about Gordie Howe: not the Gordie Howe I know, grey-haired and waving from the seats with an old Red Wings jersey and a spotlight on him, but Mr. Hockey, Mr. Elbows, the toughest man in hockey. But as a lifelong hockey fan, I still feel the need to do him justice. So I thought, why not ask my dad? Here is the first seldom-told story he gave me, smiling. When goaltender Gump Worsley broke into the NHL with the New York Rangers in 1952, Howe was just beginning the prime of his career. In a game between the Rangers and Howe's Detroit Red Wings, the 24-year-old Howe had a chance to tuck away a supposed empty-netter late in the game, with Worsley diving back towards the crease in the hope of making the save. The maskless Worsley (he was once quoted as saying ?my face is my mask?) never faced the shot. When asked later why he kept the puck on his stick, instead of risking hitting Worsley square in the face, Howe simply said he would get plenty more chances on Worsley. In March of 1962, Howe became the second player to ever score 500 NHL goals, after Maurice Richard, in a 3 ? 2 Detroit victory over the New York Rangers and Gump Worsley. -

1965-66 Toronto Maple Leafs 1965-66 Detroit Red Wings 1965

1965-66 Montreal Canadiens 1965-66 Chicago Blackhawks W L T W L T 41 21 8 OFF 3.41 37 25 8 OFF 3.43 DEF 2.47 DEF 2.67 PLAYER POS GP G A PTS PIM G A PIM PLAYER POS GP G A PTS PIM G A PIM Bobby Rousseau RW 70 30 48 78 20 13 12 2 C Bobby Hull LW 65 54 43 97 70 23 11 9 A Jean Beliveau C 67 29 48 77 50 25 24 8 B Stan Mikita F 68 30 48 78 58 35 23 16 B Henri Richard F 62 22 39 61 47 34 34 13 B Phil Esposito C 69 27 26 53 49 46 30 22 B Claude Provost RW 70 19 36 55 38 42 44 18 B Bill Hay C 68 20 31 51 20 55 38 24 C Gilles Tremblay LW 70 27 21 48 24 53 49 20 B Doug Mohns F 70 22 27 49 63 64 45 32 B Dick Duff LW 63 21 24 45 78 62 55 29 A Chico Maki RW 68 17 31 48 41 71 53 37 B Ralph Backstrom C 67 22 20 42 10 71 60 30 C Ken Wharram C 69 26 17 43 28 82 57 41 B J.C. Tremblay D 59 6 29 35 8 74 67 31 C Eric Nesterenko C 67 15 25 40 58 88 63 48 B Claude Larose RW 64 15 18 33 67 80 72 39 A Pierre Pilote D 51 2 34 36 60 89 72 55 B Jacques Laperriere D 57 6 25 31 85 82 78 49 A Pat Stapleton D 55 4 30 34 52 91 80 62 B Yvan Cournoyer F 65 18 11 29 8 90 81 49 C Ken Hodge RW 63 6 17 23 47 93 84 67 B John Ferguson RW 65 11 14 25 153 95 85 67 A Doug Jarrett D 66 4 12 16 71 95 87 76 A Jean-Guy Talbot D 59 1 14 15 50 - 88 73 B Matt Ravlich D 62 0 16 16 78 - 91 86 A Ted Harris D 53 0 13 13 87 - 92 82 A Lou Angotti (fr NYR) RW 30 4 10 14 12 97 94 87 C Terry Harper D 69 1 11 12 91 - 94 93 A Len Lunde LW 24 4 7 11 4 99 96 88 C Jim Roberts D 70 5 5 10 20 97 96 95 C Elmer Vasko D 56 1 7 8 44 - 97 93 B Dave Balon LW 45 3 7 10 24 98 97 98 B Dennis Hull LW 25 1 5 6 6